Quebec’s Place-Royale, the Reflection of a City

par Couvrette, Sébastien

Quebec City’s Place-Royale was entirely rebuilt between the late 1960s and the 1980s. Work undertaken on the site’s buildings was intended to bestow them with a heritage character evocative of the French Regime. The primary goal of this ambitious renovation project, funded by the governments of Quebec and Canada, was to make Place-Royale a major tourist attraction in Quebec City. In the process, it restored one of the site’s earliest functions as a symbolic city centre.

Article disponible en français : Place-Royale à Québec, l’image d’une ville

The “Birthplace of French America”

Boasting hundreds of thousands of visitors each year, Place-Royale is a major Quebec City tourist attraction. Travel guides tout its unique heritage value as the birthplace of French America. For countless visitors, Place-Royale’s historical authenticity is undisputed and strongly evokes the New France era. Most don’t know what the houses in Place-Royale looked like before major work done in the 1970s left them with their present-day French Regime appearance.

The Place-Royale restoration projects of the 1960s and 1970s have been widely criticized. Indeed, it is more fitting to describe the work done on the buildings of this historic district as a form of reconstruction and interpretation rather than restoration. But above and beyond the critiques and the questions over aesthetic choices, it is also worth reflecting on the present-day heritage value of Place-Royale. What is its place in the history of French America? What does today’s Place-Royale have in common with the historical Place-Royale it is meant to evoke?

A Centre of Trade

Under the French Regime, Place-Royale was first and foremost a market square and centre of trade. Construction of Samuel de Champlain’s Habitation in 1608 to serve as a trading post for the fur trade firmly established the site’s commercial vocation. The wooden building was replaced in 1624 by a second Habitation built of stone on the very same location. Notre-Dame-des-Victoires Church stands in its place today.

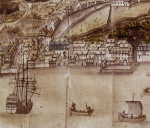

The geographic location of the point of Quebec where the Habitation stood made it a strategic place for trade and commerce. In 1633, it was the site of a major fur fair, the first of many such annual gatherings between Europeans and native peoples. Beginning in the mid-17th century, Place-Royale attracted many merchants who traded freely and took advantage of the nearby port. Colonial administrators thought the location should be more than just a place of trade, and that it should also be a symbol of the French monarchy’s power in America. As the colony’s trading hub, Quebec’s market square had to be a royal square.

The Creation of Place-Royale

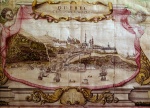

Royal squares were part of the urban built heritage of 17th century France, a place to pay homage to royalty (NOTE 1). In this spirit, intendant Jean Bochart de Champigny had a bust of Louis XIV installed in Quebec’s market square in 1686. This secured its symbolic role and, as a tangible sign of French town planning, marked it as a centrepoint of the town’s future development. The importance of the bust is evident in illustrations of Quebec from the time. In a 1688 map of New France made by the king’s cartographer, Jean-Baptiste-Louis Franquelin, the royal monument, seen from the river, is clearly visible in the middle of a street lined with two rows of houses.

But not everyone was happy with the bust. Conflicts soon arose between merchants and colonial authorities as merchants thought the monument would hurt business in Place-Royale by creating congestion in the market square (NOTE 2). The bust was therefore moved to the Intendant’s Palace in another part of town until the dispute was settled. In the end, the bust never was returned to Place-Royale. In all likelihood, it was either taken back to France by Bochart de Champigny when he left in 1702 or destroyed in the fire at the Intendant’s Palace in 1713.

Place-Royale Becomes a Royal Square Again

In the 18th and 19th centuries, Place-Royale was known as market square and Place de la Basse-Ville. With time, the episode of the Louis XIV bust faded from memory and the term “Place-Royale” fell into disuse. It was not until the turn of the 20th century that a young historian and archivist, Pierre-Georges Roy, rediscovered the story of the bust in Place-Royale. He came upon the information while conducting research in 1890 in the archives of the Sovereign Council of New France and published a few articles on the topic (NOTE 3). In 1931, a copy of the Louis XIV bust, a gift from France, was installed in Place-Royale where a fountain had been erected in the 19th century (NOTE 4). The square was officially named Place-Royale in 1937.

The First Restoration Project

In the early 1950s, art historian Gérard Morisset, then director of Inventaire des œuvres d’art de la province de Québec, drew public and provincial government attention to the importance of restoring Hôtel Chevalier to give it the French character it once had (NOTE 5). Known as the London Coffee House in the 19th century, the stone building was just steps from Place-Royale on Rue du Marché-Champlain. It was officially classified a historic monument in 1956, the second building in the district to be so designated after Notre-Dame-des-Victoires Church (NOTE 6). The following year, the provincial government purchased the building and undertook its restoration (based on limited historical information), completing the work in 1960 (NOTE 7). The Chevalier House reconstruction project became the model for built heritage conservation and served as the roadmap for the ambitious Place-Royale revitalization program (NOTE 8). The restoration style advocated for this program was the brainchild of 19th century French architect Eugène-Emmanuel Viollet-le-Duc, who influenced Gérard Morisset and for whom “restoring a building does not mean maintaining it, repairing it, or rebuilding it; it means restoring it to a state of completeness that may never have existed.” (NOTE 9)

The Revitalization of Place-Royale

The first work on a building located right on Place-Royale was completed in the early 1960s. Fornel House, named in honour of one of its owners under the French Regime, was completely rebuilt between 1960 and 1964 due to the major damage it sustained during a fire, and because its architecture had to be modified in order to reflect the French Regime style deemed appropriate for the site. Despite the changes made to the building, it retains important architectural elements from the 17th and 18th centuries. It has the foundations and indoor well from the first house built on the site in 1658, as well as vaulted stone cellars dating from 1735, parts of which lie beneath Place-Royale.

The work of architect André Robitaille, the “new” Fornel House was named a historic monument in 1964 and became the model for future work in the Place-Royale area (NOTE 10). Robitaille adopted the central tenets of the Viollet-le-Duc doctrine, advocating architectural homogeneity and unity of style in the restoration programs. By extension, he suggested working on groups of heritage buildings simultaneously rather than on individual buildings one at a time.

Following the work done on Fornel House and in keeping with Robitaille’s recommendations, the government of Quebec established a comprehensive restoration policy for the Place-Royale district, which had some run down and abandoned buildings. The 1967 Act respecting Place-Royale set in motion the ambitious Place-Royale restoration project. Work began in 1968 with the start of restoration work on Notre-Dame-des-Victoires Church.

From French Heritage to Identity and Tourism

In the 1970s, the guiding principle of the Place-Royale revitalization project was taking shape. An agreement was reached between Quebec and Ottawa in 1970 providing for significant federal funding for certain tourism projects. To supervise reconstruction work, the government of Quebec set up the Bureau de coordination de Place-Royale (BCPR). The Bureau’s job was to ensure that government intentions were respected, especially with a view to making Place-Royale a tourist destination. While highlighting certain aspects of the district’s architectural, archaeological, and historical heritage, some buildings were demolished and rebuilt in an architectural style evoking the French Regime. The scope of the restoration work and the budgets allocated for this work also stimulated job creation in the Quebec City area. Economic and budgetary considerations rather than historical reality were thus the drivers of the reconstruction process.

In addition to providing a shot in the arm to the tourism industry, the work was a response to ideological and political imperatives. As Quebec asserted its identity in the 1960s and 1970s, Place-Royale became a symbol of the province’s distinct character and francophone roots. With its French-inspired architecture, the Place-Royale project transformed this genuinely symbolic square into a site seemingly untouched by the vagaries of history, an incarnation of the urban heritage site of Ancien Régime France on the banks of the St. Lawrence River. In the 1970s, this approach was very much in keeping with renovation practices for old houses that showcased the vestiges of New France and purposely erased any traces of British architecture. Despite the strong influence of Victorian architecture in Quebec, the French heritage style continued to dominate the many new construction projects in Quebec City in the late 19th century (NOTE 11).

Contemplating the Future of Place-Royale

In the spirit of the Cultural Property Act, Place-Royale is a fixture of Quebec identity (NOTE 12). This conception of the site hearkens back to its former function as a royal square—a planned and symbolic urban centrepiece. In the 17th century, the square embodied the monarchy’s supreme power over the city and a society in the making with a monument in the likeness of the king. In the 1970s, the reconstruction project aimed to make the square the symbol of the French roots of Quebec identity. Today, debate revolves around how to make Place-Royale a vibrant place from both a conceptual and functional perspective.

Since the start of the 21st century, the goal of the Place-Royale development plan has been to restore the square’s initial commercial and residential function. Under the supervision of the Société de développement des entreprises culturelles (SODEC), in collaboration with the Commission de Place-Royale, the plan seeks to ensure Place-Royale’s economic development. In practical terms, revamping the square would entail putting in French-inspired storefronts, which would require some architectural work such as modifying façade openings. These efforts could make Place-Royale as vibrant as the neighbouring Petit Champlain district. The dual commercial and symbolic role it has played since the New France era would be secured, restoring to Place-Royale the vitality of centuries past.

Sébastien

Couvrette

Historian, Université Laval

Additional DocumentsSome documents require an additional plugin to be consulted

Images

-

Animation historique

Animation historique

à Place-Royale,... -

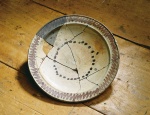

Assiette de céramique

Assiette de céramique

(Régime frança... -

Basse-ville de Québec

Basse-ville de Québec

et le London C... -

Biface de pierre du s

Biface de pierre du s

ylvicole moyen ...

-

Billes découvertes à

Billes découvertes à

la Maison Filio... -

Bol à punch (entre 17

Bol à punch (entre 17

50 et 1775) déc... -

Bouteille de vin (ent

Bouteille de vin (ent

re 1699 et 1750... -

Buste de Louis XIV à

Buste de Louis XIV à

Place-Royale en...

-

Buste de Louis XIV au

Buste de Louis XIV au

centre de Plac... -

Cafetière (entre 1761

Cafetière (entre 1761

et 1810) décou... -

Carte de l'Amérique

Carte de l'Amérique

septentrionale ... -

Champlain supervise l

Champlain supervise l

a construction ...

-

Chaudron de cuivre (e

Chaudron de cuivre (e

ntre 1645 et 16... -

Commode de pin et d'é

Commode de pin et d'é

rable galbée à ... -

Détail d'une carte mo

Détail d'une carte mo

ntrant Québec e... -

Détail de la maquette

Détail de la maquette

de Michel Berg...

-

Divers récipients à c

Divers récipients à c

ondiments décou... -

Ensemble de bâtiments

Ensemble de bâtiments

de Place-Royal... -

Entrée de serrure et

Entrée de serrure et

clé (entre 1753... -

Escalier de sauvetage

Escalier de sauvetage

en maille de f...

-

Espace découverte pou

Espace découverte pou

r les jeunes au... -

Espace découverte pou

Espace découverte pou

r les jeunes au... -

Espace découverte pou

Espace découverte pou

r les jeunes au... -

Façade de l'hôtel Lou

Façade de l'hôtel Lou

is XIV, Place R...

-

Fêtes de la Nouvelle

Fêtes de la Nouvelle

-France à Place... -

Fragment de papier pe

Fragment de papier pe

int (vers 1905)... -

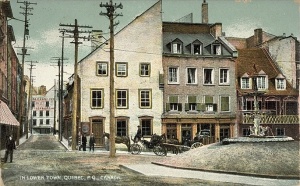

Hôtel Blanchard à Pl

Hôtel Blanchard à Pl

ace Royale vers... -

Hôtel Blanchard à Pla

Hôtel Blanchard à Pla

ce-Royale près ...

-

Hôtel Blanchard à Pla

Hôtel Blanchard à Pla

ce-Royale, vue ... -

L'une des maisons de

L'une des maisons de

Place-Royale, 2... -

L'une des vitrines th

L'une des vitrines th

ématiques du Ce... -

La «chambre à coucher

La «chambre à coucher

de Jean Talon»...

-

La «chambre à coucher

La «chambre à coucher

de Jean Talon»... -

La «salle du Conseil»

La «salle du Conseil»

ou salle à dîn... -

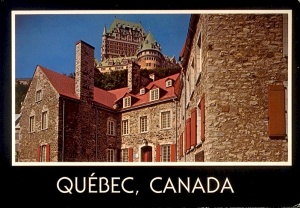

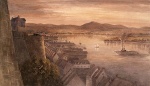

La basse-ville de Qué

La basse-ville de Qué

bec vue de la t... -

La basse-ville de Qué

La basse-ville de Qué

bec, 1778

-

La Maison Barbel à Pl

La Maison Barbel à Pl

ace-Royale en 2... -

La Maison Barbel avan

La Maison Barbel avan

t (en 1970) et ... -

La Maison Barbel avan

La Maison Barbel avan

t les travaux d... -

La Maison Leber avant

La Maison Leber avant

les travaux de...

-

Le marché de la basse

Le marché de la basse

-ville de Québe... -

Le vieux magasin du R

Le vieux magasin du R

oi tel qu'il ap... -

Maquette présentant l

Maquette présentant l

'intérieur d'un... -

Marché de la basse-vi

Marché de la basse-vi

lle de Québec e...

-

Marché de la basse-vi

Marché de la basse-vi

lle de Québec e... -

Monnaie de carte

Monnaie de carte

-

Montage présentant l'

Montage présentant l'

entreprise de r... -

Pichet à bière en grè

Pichet à bière en grè

s rhénan

-

Place Royale pendant

Place Royale pendant

le Carnaval d'h... -

Place-Royale en 1650

Place-Royale en 1650

-

Place-Royale en 1759

Place-Royale en 1759

-

Place-Royale en 1850

Place-Royale en 1850

-

Québec: le marché Fin

Québec: le marché Fin

lay et ses quai... -

Quelques artefacts li

Quelques artefacts li

és à l'alimenta... -

Vaisselle de porcelai

Vaisselle de porcelai

ne découverte à... -

Vue de l'église de No

Vue de l'église de No

tre-Dame-des-Vi...

Catégories

Notes

1. En France, les plus anciennes places royales apparaissent au début du XVIIe siècle sous Henri IV, avec la Place des Vosges et la Place Dauphine. Par la suite, sous Louis XIV et Louis XV, le procédé se répandra et se codifiera. Richard L. Cleary, Place Royale and Urban Design in the Ancien Régime, Cambridge, Cambridge University Press, [1999] 2011.

2. Un discours similaire sera tenu à l’égard de l’église-Notre-Dame-des-Victoires dans la première moitié du XIXe siècle.

3. En 1890, il écrit un premier article dans sa revue historique Le Glaneur. Il récidive en 1915 dans le Bulletin des recherches historiques, dont il est également le maître d’œuvre.

4. Cette fontaine se situait vers le centre de la place. Le buste sera déplacé à l’endroit qu’il occupe actuellement dans les années 1980. Pour les détails entourant la découverte de l’existence du buste original et la mise en place du second buste, voir Noppen et Morisset, « De la ville idéelle à la ville idéale… ».

5. À partir de 1937, l’Inventaire des œuvres d’art de la province de Québec remplace la Commission des monuments historiques comme institution responsable de la mise en valeur patrimoniale de l’architecture québécoise. Lucie K. Morisset, Des régimes d’authenticité. Essai sur la mémoire patrimoniale, Québec, Presses universitaires de Rennes, Presses de l’Université du Québec, 2009, p. 113. Gérard Morisset, « L’hôtel Chevalier à Québec », La Patrie, 1ermars 1953, p. 36-37. Gérard Morisset, Mémoire sur l’hôtel Chevalier à Québec, Québec, Commission des monuments historiques, 1955.

6. Pour des informations concernant la maison Chevalier, consulter le lien suivant : Maison Chevalier.

7. Cette acquisition se fait en en vertu des modifications apportées au début des années 1950 à la loi sur les monuments historiques de 1922. L’Hôtel Chevalier est le premier édifice à être acquis par le gouvernement à la suite des changements apportés à la loi. http://www.mcccf.gouv.qc.ca/index.php?id=819

8. L’actuelle maison Chevalier constitue un ensemble domiciliaire comportant deux autres maisons : la maison Chesnay et la maison Frérot. Les chemins de la mémoire. Monuments et sites historiques du Québec, tome 1, Québec, Les Publications du Québec, 1991. Morisset, Des régimes d’authenticité…, p. 114.

9. Eugène-Emmanuel Viollet-le-Duc, Dictionnaire raisonné de l’architecture française du XIe au XVIe siècle - Tome 8, Paris, A. Morel et Cie, 1875, p. 14.

10. Sur la maison Fornel, suivre le lien suivant : Maison Fornel.

11. À la suite de l’avènement de la Confédération canadienne en 1867, des architectes québécois comme Eugène-Étienne Taché et Joseph-Ferdinand Peachy, encouragés par le gouvernement du Québec, vont chercher à affirmer l’identité française de l’architecture québécoise à travers la conception d’édifices et de maisons du Vieux-Québec et de ses environs. L’Hôtel du Parlement (1877-1886) et le Pavillon Camille-Roy (1855-1875) du Séminaire de Québec (anciennement le pavillon central de l’Université Laval) s’inscrivent dans cette mouvance. Luc Noppen, « L’image française du Vieux-Québec », Cap-aux-Diamants, vol. 2, no 2 (1986), p. 13-17.

12. À partir des années 1920, à la suite de l’élection du Premier ministre Louis-Alexandre Taschereau, le gouvernement provincial fait preuve d’une volonté implicite de refrancisation et de préservation du patrimoine francophone de la ville de Québec. En 1922, le gouvernement vote une loi qui donnera naissance à la Commission des monuments historiques, étape décisive vers une protection juridique du patrimoine. Cette loi, modifiée en 1952 et 1963, sera remplacée en 1972 par la Loi sur les biens culturels qui augmentera considérablement le pouvoir d’intervention de l’État sur la valorisation et la préservation des biens patrimoniaux. Muni de cet important outil légal, le gouvernement du Québec sera le véritable maître d’œuvre du projet de reconstruction de la Place-Royale. Son intervention redonnera au « berceau de l’Amérique française » son caractère francophone, effaçant par la même occasion, à cet endroit, toute référence à son passé de ville anglaise. Pour un aperçu de l’historique de la protection du patrimoine par le gouvernement du Québec. http://www.mcccf.gouv.qc.ca/index.php?id=2398

Bibliographie

Les chemins de la mémoire. Monuments et sites historiques du Québec, tome 1, Québec, Les Publications du Québec, 1991.

Cousson, Claire, « La constitution de Place-Royale en lieu symbolique : entre construction identitaire et promotion touristique », Rabaska : revue d’ethnologie de l’Amérique française, vol. 8 (2010), p. 19-28.

Côté, Renée, Place-Royale : quatre siècles d'histoire, Montréal, Musée de la civilisation, Fides, 2000, p. 56.

Faure, Isabelle, « La reconstruction de Place-Royale à Québec », Cahiers de géographie du Québec, vol. 36, no 98 (1992), p. 324-325.

Faure, Isabelle, « Critique du projet de Place Royale à travers les valeurs investies dans sa politique de conservation », Urban History Review/Revue d’histoire urbaine, vol. 25, no 1 (1996), p. 48.

Morisset, Lucie K., Des régimes d’authenticité. Essai sur la mémoire patrimoniale, Québec, Presses universitaires de Rennes, Presses de l’Université du Québec, 2009, p. 113.

Noppen, Luc, « L’image française du Vieux-Québec », Cap-aux-Diamants, vol. 2, no 2 (1986), p. 13-17.

Noppen, Luc et Lucie K. Morisset, « De la ville idéelle à la ville idéale : l’invention de la place royale à Québec », Revue d’histoire de l’Amérique française, vol. 56, no 4 (2003), p. 453-479.

Noppen, Luc et Lucie K. Morisset, Au cœur de la ville marchande, Place-Royale : la valorisation architecturale de la fonction commerciale, Montréal, SODEC, 2003.