The Point: a Franco-American Heritage Site in Salem, Massachusetts

par Blood, Elizabeth and Duclos-Orsello, Elizabeth

Salem, Massachusetts is a cultural palimpsest, a geographical space that bears traces of communities of people who have called this city their own. French-Canadians, who immigrated to Salem in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, made their mark in a neighborhood called “The Point.” A devastating fire razed the neighborhood in 1914, forcing its French-Canadian and Franco-American inhabitants to reimagine and rebuild it. One hundred years later, the Point was named to the National Register of Historic Places in the United States due to the uniformity of its architectural style and its cultural importance to Salem’s Franco-American community.

An Immigrant Neighborhood

While Salem today is most known for its Halloween festivities, many also acknowledge the Native Americans who were the original inhabitants of this land, the Puritans and the women they condemned as witches here in the 17th century, and the famous 19th-century Anglo-American authors like Nathaniel Hawthorne whose legacy is memorialized with statues and tourist sites throughout the city. Less well-known is the history of the several waves of immigrants—including an important francophone population of French-Canadian immigrants and their descendants—who have transformed the socio-cultural, economic and physical space of this city since the mid nineteenth century. The Point’s recognition as a national historic site affirms and formally marks on the city’s landscape the locations of work, play, worship, business and community life built by generations of French-Canadian and Franco-American residents, a group of people who shaped all areas of life in Salem for more than a century. [Illustration 1]

Between 1840 and 1930, approximately 900,000 French-speaking Canadians left Québec to find work in the United States, and many were drawn to New England’s manufacturing industries. Salem, with its textile mills and leather factories, was one of a number of popular destinations. In the first decades of the 20th century, French-Canadian immigrants from Quebec and their Franco-American children made up over 20% of Salem’s population, a significant percentage which rivalled some of the other popular French-Canadian destinations in New England, and the Point neighborhood in which they originally clustered was dubbed a Petit Canada or Little Canada. As they did in other New England cities like Lowell, Worcester, and Fall River in Massachusetts, Woonsocket in Rhode Island, Lewiston in Maine, and Manchester in New Hampshire, the Franco-Americans of Salem built churches and schools, started businesses and opened shops, created credit unions, newspapers, and social clubs. They eventually became teachers, policemen, firemen, doctors and nurses, lawyers, tradesmen, business people, professionals and politicians. They held on to French-Canadian traditions while beginning new traditions in their Franco-American families. They changed the city just as they themselves were changed by it.

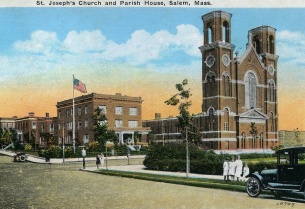

The neighborhood called the Point (la Pointe to French speakers) was historically the most populous of two main French-speaking neighborhoods in Salem. Located east of Lafayette Street, from Leavitt Street to Peabody Street, between the South River and Palmer Cove, this area was anchored by St. Joseph’s, the city’s first French-language church, to the west and the Naumkeag Steam Cotton Company to the east. [Illustration 2] Many of the Point’s inhabitants were Naumkeag mill workers and their families. The St. Joseph’s church and school were the center of the neighborhood’s spiritual, social and cultural life. Large families lived in triple-decker homes and apartment buildings, some of which were owned by the mill. The streets were peppered with corner markets, variety stores, businesses, clubs and bars catering to the French-speakers in the neighborhood.

French was the first language of new immigrants and of their first-, second- and even third- and fourth-generation Franco-American children. Children attended the parish school, where French-speaking women religious offered half-day instruction in English and half-day in French. The neighbors all knew each other and children played in the streets and at what is now the Palmer Cove Park. One of the most common memories of Franco-Americans raised in this neighborhood is the smell of pork cooking in almost every kitchen as mothers and grandmothers worked to feed large families with Franco-American favorites like tourtière, a pork pie, and a pork spread called cretons or gorton.

The Great Fire of 1914

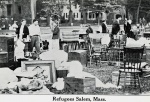

In June of 1914, on the eve of the worst fire the city had ever experienced, the Franco-American community had just opened their new brick church which had over 16,000 registered parishioners. [Illustration 3] On June 25th, the Great Fire of Salem spread from a leather tanning factory in north Salem down to the city center, destroying all in its path, including the vast majority of buildings in the city’s Point neighborhood. The fire reduced to rubble the Naumkeag Steam Cotton mill and all but the spires of the newly built St. Joseph’s. In the end, over 1,800 buildings were destroyed and approximately 15,000 people displaced. Astonishingly, there were no deaths. The Francophone community living in the Point was the hardest hit by the fire. [Illustration 4] Among the 3,500 Salem residents left homeless, the largest percentage were from the St. Joseph’s parish, and many lived in tents called “refugee camps” on the Salem Common and in Forest River Park for months. Thousands also left Salem to move to surrounding communities like Lynn and Beverly. Some chose to stay with relatives in other states like New Hampshire, while others returned to their homeland in Canada.

Families who stayed in Salem were in need of shelter, food and clothing. Aid poured in from the government, the Red Cross, and local organizations and individuals. Other nearby Franco-American communities, such as the one in Lowell, Massachusetts, held fundraisers to contribute to those displaced by the fire. Benefit shows were held in local theaters. Businesses offered special deals or donations of shoes and clothes. Tourists also poured into Salem to view the expanse of rubble in areas razed by the fire. Almost immediately, however, the Franco-American community demonstrated its will to clean up and rebuild. An editorial by Arthur Beaucage entitled “L’Incendie de notre ville” (“The Fire in Our City”) was published in the local French-language newspaper Le Courrier de Salem in the first edition after the fire, on the eve of 4th of July, encapsulating the community’s resilience and commitment to rebuilding “their” city anew:

“Haut les coeurs, donc, et courage, espoir et confiance! Bien avant que le premier rayon de soleil de 1915 ait doré l’horizon, il ne restera plus de cette catastrophe sans nom que la sinistre date et l’horrible souvenir” (Note 1)

“Chin up, then, and have courage, hope and faith! Well before the first ray of sun of 1915 gilds the horizon, nothing will be left of this nameless catastrophe, except the sinister date and the horrible memory”

Before the fire, the vast majority of buildings in the Point neighborhood were wooden multi-family homes and apartment buildings, often labeled tenements, packed closely together with limited green spaces. After the fire, the city established the Salem Rebuilding Commission (SRC) to report on the state of affected areas in Salem and to oversee their reconstruction. The SRC report noted that pre-fire, the wood buildings in the Point neighborhood were so close together that residents could reach out of one kitchen window into another. Their new vision for the neighborhood, informed by reform-era ideology, included wider streets, green spaces and parks, and more durable brick buildings. In fact, per SRC regulations, 30% of new buildings were required to be built in masonry (brick or brick veneer). Only those homes built on a smaller scale were allowed to be constructed in wood, so in order to avoid the masonry requirement, residents constructed more four-family houses, rather than the typical six-unit triple-deckers that can today be found in working class neighborhoods throughout eastern Massachusetts. The characteristic four-family homes were Colonial Revival-style three-bay structures featuring hipped roofs with two-story central entrance porches flanked by square columns and turned balusters.

Others seized the opportunity to build larger brick apartment buildings or commercial buildings, which remain today the most visually distinct building form in neighborhood. [Illustration 5] These long, linear 2-4 story Colonial Revival buildings with flat roofs feature many distinctive architectural features, including decorative brickwork around windows and doorways, cornices, fanlights, and other embellishments. Many of the buildings in this neighborhood, particularly in the areas along Lafayette street near the site of the old St. Joseph’s church and around what is today Lafayette Park, still proudly bear the names of the Franco-American families who built them. Inscribed over the entryways are names like Audet, Napoleon, Gagnon, and Martel and at ground level one sees cornerstones boasting build completion dates of 1915, 1918 or 1920.

Saint Joseph’s Church

As life returned to normal in the years immediately post-fire, families returned and businesses reopened. So too did the Naumkeag Mill and the St. Joseph’s church and school. The buildings surrounding the church, including the rectory and the St. Joseph’s School, were rebuilt slowly as parish funds were available. The church itself was the last to be reconstructed. Parishioners worshiped in the basement of the fire-damaged church, the only part of the edifice not destroyed, until the 1940’s when funds for a new church allowed for its replacement. The new church was funded by donations from then prominent Franco-American professionals, business owners and community leaders, clergy members, and hundreds of parishioners, as well as donations from large companies in Salem who relied on the Franco-American workforce (The Naumkeag Steam Cotton Company, Hytron, Sylvania, and the department store of Almy, Bigelow & Washburn). Along with the church, the parish commissioned a monument that was donated to the City of Salem entitled “La Victoire du deuil” (“Mourning Victory”) and designed by Norman Nault, a Franco-American from Worcester and graduate of the Harvard School of Architecture. The monument commemorates the 2,105 parishioners of St. Joseph’s who served in World War I and World War II and bears the inscription: “Time will not dim the glory of their deeds”. [Illustration 6] The commemoration ceremony, attended by prominent members of the local and state government was chronicled by church historians who reported the following speech made by church representatives:

"Notre pays est devenu grand et fort à cause de son attitude en fait de tolérance. Il fut formé de nationalités venant de tous les pays...Ce monument attestera puissamment de notre dévotion, de notre patriotisme, et des sacrifices de nos Américains de descendance française. Puisse-t-il toujours être une source d'inspiration pour la jeunesse de notre ville et un exemple de tolérance et d'égalité." (Note 2)

"Our country has become great and strong because of its belief in tolerance. It was formed by people from nations all over the world...This monument will strongly attest to our devotion, our patriotism, and the sacrifices of Americans of French descent. May it always be an inspiration to the youth of our city and an example of tolerance and equality.”

The monument still stands today in Lafayette Place park even though the church does not. The diocese closed the church in 2004 and sold the land. The building was razed in 2013, replaced by a mixed-use residential and commercial building. The statue of St. Joseph that once adorned the 1913 steeple and was buried on the site of the 1948 church was re-interred on the site in a public ceremony in 2013 and now lays under the ground behind the current building: a hidden symbol of an institution that was the heart and soul of the Franco-American community in Salem for many generations.

The Evolution of the Franco-American Community

During the mid to late 20th century, the Franco-American community continued to grow and flourish as Franco-Americans became part of the city’s political, economic, social and cultural fabric. The city had a Franco-American mayor, Jean Levesque, who served from 1973 to 1983, and a Franco-American Chief of Police, Robert St. Pierre, who was the longest serving chief from 1984 to 2009, both of whom were born and raised in the Point. Franco-Americans also became teachers, lawyers, firemen, professionals and business owners. With the close of the mill in the 1950’s and the continued advancement of Franco-Americans into the middle and upper classes through higher education and enhanced employment opportunities, Franco-Americans began to move out of the Point and into single family homes in other neighborhoods and surrounding communities. A new wave of immigration from the Caribbean and Latin America in the 1980’s brought many changes to the Point, where today one is more likely to hear Spanish than French, to find a restaurant serving pastellitos rather than a market selling the makings for tourtière.

However, this is not simply the story of one ethnic group replacing another. As in the case in so many cities across New England, Salem today is a palimpsest: a city where there are remnants and traces of the layers of the past, of the peoples, cultures and sites that have shaped it over centuries. The lives and locations of French-Canadian and Franco-American Salem, and the built environment that is their legacy, have been essential in the transformation of Salem’s identity. From an identity centered on Anglo-American colonial and literary history to one marked by the dynamic and layered histories of immigrants.

A visitor to Salem can see this in the Point’s distinctive architecture, in the buildings inscribed with Franco-American names, and in the monument in Lafayette Park. These sites of memory hold the stories of so many who shaped the city a century ago. And much remains of the Franco community in Salem, including many Franco-owned or operated businesses that still thrive in the Point and Lower Lafayette business district, as well as the central business district. There are two French-language social clubs in Salem, the Club Richelieu and the Club Nord-de-Boston, both initiated by the leaders of St. Joseph’s in the 1960’s in an attempt to preserve the use of the French language by new generations of Franco-Americans. And, there are the people. According to the 2010 census (http://censusviewer.com/city/MA/Salem/2010), nearly 10% of Salem residents self-identify as being of French origin and likely many more who can identify at least one ancestor of French origin. Their ongoing presence and active participation continues to make this place the vibrant city it is today.

Dr. Elizabeth Blood, Professor of French

Dr. Elizabeth Duclos-Orsello, Professor of American Studies

Salem State University

Additional DocumentsSome documents require an additional plugin to be consulted

Images

-

“Refugees” with house

“Refugees” with house

hold belongings... -

Aerial view of The Po

Aerial view of The Po

int neighborhoo... -

Colonial revival buil

Colonial revival buil

dings as seen i... -

Destruction of the Po

Destruction of the Po

int neighborhoo...

-

Dinner time at the “r

Dinner time at the “r

efugee camp” in... -

Gagnon’s Shoe Repair,

Gagnon’s Shoe Repair,

a Franco-Ameri... -

Header of the Courrie

Header of the Courrie

r de Salem, Sal... -

Many immigrants left

Many immigrants left

French Canada t...

-

Mill workers leaving

Mill workers leaving

the Naumkeag St... -

Monument La Victoire

Monument La Victoire

du Deuil in Laf... -

New building construc

New building construc

ted on the site... -

Postcard depicting St

Postcard depicting St

. Joseph’s Chur...

-

Statue of Nathaniel H

Statue of Nathaniel H

awthorne in Sal... -

The former rectory of

The former rectory of

St. Joseph’s c... -

The ruins of St. Jose

The ruins of St. Jose

ph’s Church aft...

Catégories

Notes

Note 1 : Beaucage, Arthur, « L’incendie de notre ville », Le Courrier de Salem, 3 juillet 1914.

Note 2 : La Paroisse Saint-Joseph: Salem, Massachusetts, Salem, Association Laurier, 1948.

Bibliographie

Franco-Americans in Salem:

La Paroisse Saint-Joseph: Salem, Massachusetts, Salem, Association Laurier, 1948.

Curley, Jerome M. and Nelson L. Dionne, Salem: Then & Now, Charleston, SC, Arcadia Publishing, 2009.

Donnell, Robert P., ed., Locational response to catastrophe: the shoe and leather industry of Salem, Massachusetts, after the conflagration of June 25, 1914, Syracuse NY, Syracuse University, 1976.

Kampas, Barbara Pero, The Great Salem Fire of 1914, Charleston, SC, The History Press, 2008.

Franco-Americans in New England

Brault, Gerard J., The French-Canadian Heritage in New England, Lebanon, NH, University Press of New England, 1986.

Fox, Cynthia A., "Franco-American Voices: French in the Northeastern United States Today", The French Review, no. 80, 2007, pp. 1278-1292.

Gosnell, Jonathan, "Between Dream and Reality in Franco-America", The French Review, no. 80, 2007, pp. 1336-1349.

Roby, Yves, The Franco-Americans of New England: Dreams and Realities, Mary Ricard, Trans. Montréal, Septentrion, 2004.

Audiovisual and online resources:

- “Franco-American Oral Histories”, University of Maine Franco-American Centre, site consulted 30/01/17 [online], http://francoamericanarchives.org/

- “Franco-American History”, Marianopolis College, site consulted 30/01/17, http://faculty.marianopolis.edu/c.belanger/QuebecHistory/frncdns/default.htm

- “Franco Heritage in Salem, Massachusetts”, Maple Stars and Stripes, site consulted 30/01/17 http://maplestarsandstripes.com/shownotes/mss-032-franco-heritage-in-salem-massachusetts/

- “Great Salem Fire of 1914”, Salem State University Library Digital Commons, site consulted 30/01/17, http://digitalcommons.salemstate.edu/salem_fire/

- “Franco-American Oral History Project”, Salem State University Archives and Special Collections, site consulted 30/01/17, http://www.salemstate.edu/library/28306.php (the videos are not yet available online, except a few clips are on YouTube like this interview with Robert St. Pierre : https://youtu.be/S7b6wci0VZI )