The Guigues Elementary School in Ottawa

par Pelletier, Jean Yves

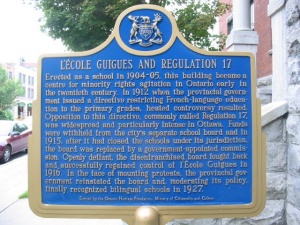

In front of the old Guigues elementary school in Ottawa, two historic plaques, one erected by the City of Ottawa and the other by the Ontario Heritage Trust, bear witness to the epic battle Ontario francophones fought to save their schools and conserve French as a language of instruction in their province. The plaques serve as a reminder that the Guigues elementary school was at the heart of a movement to protect minority rights in Ontario at a time when, in 1912, a provincial directive commonly known as Regulation 17 ordered that French-language education be limited to the first two years of elementary school. An outcry of protests, notably at the Guigues elementary school in 1915-1916, forced the government to soften its policy and, in 1927, bilingual schools were officially recognized in Ontario.

Article disponible en français : École Guigues d’Ottawa

A predominant role, a major symbol

Guigues elementary school has played a significant part in the development of a Franco-Ontarian identity and collective memory. Serving as an educational centre for young Franco-Ontarians for over a century, the Guigues elementary school is one of the most well-known French schools in French Ontario. The school, which for a time was for boys only and then coeducational, was run for a hundred years by the Brothers of the Christian Schools, and also for a few years at the turn of the 20th century by the Sisters of Charity of Ottawa.

The school, located on Murray Street in Ottawa’s Lower Town district, was originally opened in 1864. Built by the Ottawa Roman Catholic Separate School Board, it is initially called the Central School, but in 1889 it is renamed “l’école Guigues” [Guigues elementary school] in honour of Monsignor Joseph-Eugène-Bruno Guigues, O.M.I., Ottawa’s first bishop. With an increasing number of pupils, a new school is built of stone and brick in 1904. Over the years, the school has welcomed thousands of students and many of its graduates have gone on to become important leaders of the Franco-Ontarian community. However, what sets this Ontario French-language school apart from all the others is its predominant role in the Franco-Ontarian resistance movement against the unjust Regulation 17 that greatly restricted the teaching of French in Ontario schools.

Diane and Béatrice Desloges: heroines in the struggle against Regulation 17

Right from the start of the 1915 school year, two sisters, Diane Desloges and Béatrice Desloges, natives of Ottawa and both teachers at the Guigues elementary school, refuse to implement the provisions of Regulation 17, thus defying the ministerial order [issued by the Ontario ministry of Education] that limits teaching in French to the first two years of elementary school. Because the two teachers vigorously oppose the Regulation, in October, a temporary school board appointed by the provincial government (nicknamed “Petite Commission” or Small Board), bans them from entering the Guigues elementary school property. The Desloges sisters, with the support of some parents and members of the community, decide to open clandestine classes in a “free school” located in a church basement and later in a commercial building. They maintain their steadfast opposition, even after the provincial authorities refuse to pay them their salaries and revoke their teaching certificates. Students leave the Guigues elementary school in droves and the teachers hired to replace the Desloges sisters soon find themselves alone in the empty building!

Both French and English newspapers of the period report on the exploits of the Desloges sisters, and public protests are organized. After a few months of uncertainty, the parents decide they have had enough and a popular movement of civil disobedience is launched. A group of women – for the most part the mothers of pupils – storm the Guigues school and, after what comes to be known as the “battle of the hatpins,” a few teachers and mothers undertake a long siege of the “school of resistance.”

The resistance becomes organized

On Tuesday, January 4th, 1916, a group of mothers armed with scissors and hatpins manage to occupy the Guigues elementary school and begin guarding the school’s entrance (Note 1). The Small Board reacts swiftly and obtains a court injunction ordering the Desloges sisters to immediately leave the school grounds or face arrest and imprisonment. But the Desloges sisters refuse to obey and, protected by the mothers of their pupils known as the “school guardians,” they continue teaching for two days. At night, the pupils, the staff and the guardians go home.

On Friday, January 7th, there is a sensational turn of events: inside the school, policemen are waiting for the Desloges sisters and their “guardians” and they try to prevent them from entering the building. But some parents, both men and women, manage nevertheless to gain access to the school with a group of pupils. They, in turn, allow the Desloges sisters to enter the school through a window. A meeting takes place inside the school while the Small Board’s president, Arthur Charbonneau, tries to get the protesters to accept the new teachers that he has appointed to replace the Desloges sisters. But the opposite happens. The parents at the school force Charbonneau to resign and physically remove him from the premises. Later that same day, Samuel Genest, the chairman of the Ottawa Catholic Separate School Board, arrives in the afternoon to hail the victory of the parents.

From that day on, the “school guardians” remain at their post day and night and the Desloges sisters resume teaching the following Monday. The movement gains momentum. At the end of January 1916, French students in Ottawa take part in a series of protests, and in particular one held on January 31st, where they send a delegation to City Hall to demand that the salaries owed to their teachers be paid. Their pleas go unheeded.

The Association canadienne-française d’éducation d’Ontario (ACFEO) [French-Canadian Association for Education in Ontario] and the Ottawa Roman Catholic Separate School Board (ORCSSB) decide to adopt an even more aggressive strategy. The schools of the ORCSSB shut down and, on February 11th, 1916, 4,300 striking students from these schools march in protest in the streets of Ottawa waving signs and singing a song against Regulation 17 to the tune of “It’s a long way to Tipperary.” World War I is raging at the time, and this popular song serves as a rallying cry for all those in uniform. Joining the ranks of the students of all the other bilingual schools in the city, the pupils of the Guigues elementary school take part in this protest march in front of the Parliament of Canada and in the streets of Ottawa.

A number of protests take place, one after the other, until the spring of 1916, while the “guardians of the school” maintain their vigil in the schools on strike until June. In order to thwart any attempt by the provincial authorities to expel the teaching staff, groups of women, mostly the mothers of pupils, remain on guard in front of the school armed with their hatpins, led by Diane and Béatrice Desloges. Finally, with the beginning of the school year in the fall of 1916, the schools are reopened. In November of the same year, the Privy Council of London, at that time the highest court in Canada’s justice system, rules that the Small Board is illegal. Consequently, the ORCSSB resumes its normal activities and pays the teachers their salaries in arrears.

The last chapter of this epic struggle unfolds when anglophone ratepayers take the chairman of the ORCSSB to court over his decision to authorize the payment of the teachers’ salaries in arrears. It takes the personal intervention of the pope, Benedict XV, who orders Ontario Catholics not to take legal action against each other for questions pertaining to language rights, to put an end to the legal proceedings. But, since the issue at the heart of the matter is still not settled, the ORCSSB continues its opposition to Regulation 17. The crisis finally comes to an end in 1921 and bilingual schools in the province are officially recognized in 1927.

The road to celebrating the heritage of the Guigues elementary school

The Guigues elementary school earned its badge of honour during the events surrounding the opposition to Regulation 17. A council of friends of the school was founded in 1920 and remained very active until the 1950s. In 1979, a celebration marks 75 years of the historic building with open house days, during which hundreds of people visit the school and receive a copy of a souvenir booklet produced for the occasion. However, a dark cloud casts its shadow over the event since, in the summer of 1979, the school board announces the school’s closure due to declining enrolment. The building, deemed surplus to requirements by the school board, is rented out during the 1980s.

Over a period of fifteen years, from 1979 to 1994, many efforts are made to preserve the old Guigues elementary school. Because of the building’s historic and symbolic importance, several potential projects are put forward to give it new life: cultural centre, theatre centre, archive. Unfortunately, all of these attempts prove unsuccessful. The condition of the decommissioned school, which remains without a tenant and unheated since the end of the 1980s, deteriorates to a critical state. Swift action is required. In 1992, when the old Guigues elementary school is put up for sale by the Catholic division of the Conseil scolaire de langue française d’Ottawa-Carleton [Ottawa-Carleton French-language school board], a group of individuals concerned about Franco-Ontarian heritage conservation meets with the Regroupement des organismes du patrimoine franco-ontarien (ROPFO) [Network of Franco-Ontarian Heritage Organizations] to discuss the situation.

The Guigues elementary school being an important symbol for the Franco-Ontarian community of its struggle to have its education rights recognized, and also the scene of so many key events in the fight for French-language education in Ontario during the time of Regulation 17, everyone is keenly aware of the need to protect this heritage building. A committee to save the school is formed on the spot, and private and public meetings are organized with the media, the public, and civic authorities. As part of its objectives, the committee prevents the building from being demolished in the short term while it searches for suitable francophone buyers for the school. Five female activists form a subcommittee of “new women guardians” that becomes the public face of the committee to save the school.

After months of efforts, an ideal buyer, a francophone seniors’ day care centre, the Centre polyvalent des aînés francophones d’Ottawa-Carleton (CPAFOC), comes forward with an offer. Finally, in 1994, this organization signs a contract to purchase the former school. The adult day care centre’s administration sets up its offices in the building and enters into a partnership with a contractor to renovate the upper floors into condominiums. The cost of these renovations rises to $4 million; every level of government signs on to the project and the Franco-Ontarian community raises approximately half a million dollars through an aggressive fund-raising campaign. Working with the CPAFOC’s management, a committee oversees the renovations to ensure that they conform to heritage building standards and that they include a heritage space (designing a permanent historical exhibition and naming some of the rooms for famous Franco-Ontarian men and women from Ottawa). This committee also undertakes the establishment of an archive.

The building is renovated in 1996-1997 and the adult day programme centre, le Centre de jour, renamed “Centre de jour Guigues,” is finally opened. The official opening takes place on May 30th, 1997, before a crowd of several hundred guests. The unveiling of a permanent heritage space and the launch of a souvenir booklet mark the occasion. All those present at the celebration are beaming with pride, and with good reason. Seventy years after saving French-language education in Ontario, the Guigues elementary school is also finally saved.

The determination of the two Desloges sisters earned them the admiration of the entire Franco-Ontarian community and turned them into a symbol of the resistance to Regulation 17. In 1997, the francophone community of Ottawa, which has never forgotten the key role played by these two teachers, named a new high school opened in Orléans, a suburb of Ottawa, Béatrice-Desloges in honour of these heroines.

The Guigues elementary school, a central element in the teaching of Franco-Ontarian history

The occupation of the Guigues elementary school is a spectacular illustration of a grassroots resistance strategy. The teachers demonstrated exceptional devotion and courage during the struggle to ensure French-language education for Franco-Ontarian students, as did the mothers of the children who mustered to defend the school. The highly symbolic “hatpins” incident so galvanized the opposition against Regulation 17 that the ensuing outcry of protests forced the provincial government to soften its policy. Through its contribution to saving French-language education in Ontario, the Guigues elementary school serves as a strong symbol of Franco-Ontarian identity.

Jean Yves Pelletier

Heritage consultant, Ottawa.

Additional DocumentsSome documents require an additional plugin to be consulted

Images

-

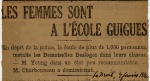

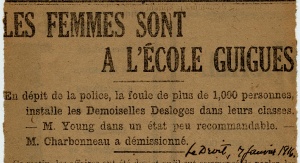

“The women are at the

“The women are at the

Guigues elemen... -

A scene from the play

A scene from the play

“Oui l’automat... -

Brigadiers de l’école

Brigadiers de l’école

Guigues, 1949-... -

École Guigues, classe

École Guigues, classe

de 8e année, 1...

-

Finissants de l’école

Finissants de l’école

Guigues, 1960... -

Frère Cyprien Ouellet

Frère Cyprien Ouellet

te, directeur d... -

Guigues elementary sc

Guigues elementary sc

hool, 2009. -

La chorale des Petits

La chorale des Petits

chanteurs de l...

-

Membres de la Ligue A

Membres de la Ligue A

micale Guigues ... -

Ontario Heritage Trus

Ontario Heritage Trus

t plaque in fro... -

Personnel enseignant

Personnel enseignant

de l’école Guig... -

School children prote

School children prote

sting against R...

-

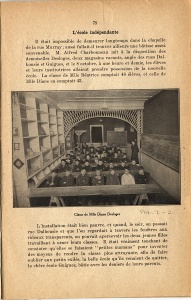

The class of Miss Dia

The class of Miss Dia

ne Desloges in ... -

The Guigues elementar

The Guigues elementar

y school guardi... -

The Guigues elementar

The Guigues elementar

y school, Ottaw... -

Une chanson sur le Rè

Une chanson sur le Rè

glement 17 sur ...

Catégories

Notes

1. This partial account of the events of the Regulation 17 crisis is taken from information included in the virtual exhibition project “La présence française en Ontario : 1610, passeport pour 2010” [The French presence in Ontario: 1610, a passport for 2010], presented online by the Centre for Research on French Canadian Culture (Centre de recherche en civilisation canadienne-française) of the Univerisity of Ottawa.

Bibliographie

Album-souvenir du 75e anniversaire de l’école Guigues : 1904 à 1979, Ottawa, Le Conseil des écoles séparées catholiques d’Ottawa, 1979, 112 p.

Le Centre artistique Guigues : étude de faisabilité/Guigues Centre for the Arts : project presentation, préparé par Marie Lanoue, Marc Gendron, André Thériault [Ottawa, 1982], 68 p.

« Le Centre de jour Guigues : un bel exemple de préservation et de conservation historique d’un édifice riche en patrimoine », dans Newsletter/Bulletin, Council of Heritage Organizations in Ottawa/Conseil des organismes du patrimoine d’Ottawa, no 21, juillet 1997, p. 11-12. (Article reproduit dans Fleur-de-trille, Ottawa, Regroupement des organismes du patrimoine franco-ontarien, automne 1997).

L’école Guigues : fanal de la francophonie/L’École Guigues: Minority’s landmark. Ottawa, Ottawa, Comité local pour la conservation de l’architecture/Local Architectural Conservation Advisory Committee, 1980, [15] p.

« L’école Guigues… l’école de la résistance », dans Le Métropolitain (Toronto), semaine du 9 au 16 janvier 1996, p. 2.

PELLETIER, Jean Yves, Cahier-souvenir de l’École Guigues d’Ottawa (1864-1997), Ottawa, J.Y. Pelletier et Centre de jour Guigues, 1997, 34 p.

PELLETIER, Jean Yves, L’école Guigues d’Ottawa. Chronologie des événements. Première partie : dates importantes depuis la fermeture de l’école (1978-1992). Deuxième partie : dossier de presse (1981-1992). Troisième partie : dossier historique (1864-1992), Toronto, chez l’auteur, 2 décembre 1992, 60 p.

SOCIÉTÉ SAINT-JEAN-BAPTISTE D’OTTAWA. SECTION NOTRE-DAME. Livre d’or de l’école Guigues, Ottawa, Imprimerie Le Droit, 1917, 93 p.

Lectures complémentaires

ASSELIN, J.-A. Émile, Les mamans ontariennes, Ottawa, Le Droit, 1917, 43 p.

BEGLEY, Michael, Le règlement XVII : l’étude d’une crise, Ottawa, Association des enseignants franco-ontariens, 1979, 41 p.

CHOQUETTE, Robert, La foi gardienne de la langue en Ontario, 1900-1950, Montréal, Bellarmin, 1987, 282 p.

GODBOUT, Arthur, Historique de l’enseignement français dans l’Ontario 1676-1976, Ottawa, Centre franco-ontarien de ressources pédagogiques, 1979, 102 p.

GODBOUT, Arthur, L’origine des écoles françaises dans l’Ontario, Ottawa, Éditions de l’Université d’Ottawa, 1972, xvi-183 p.

GODBOUT, Arthur, Nos écoles franco-ontariennes : histoire des écoles de langue française dans l’Ontario, des origines du système scolaire (1841) jusqu’à nos jours, Ottawa, Éditions de l’Université d’Ottawa, 1980, 144 p.

SIMON, Victor, Le règlement XVII : sa mise en vigueur à travers l’Ontario, 1912-1927, Sudbury, Société historique du Nouvel-Ontario, collection « Documents historiques » no 78, 1983, 58 p.

![A scene from the play Oui lautomate obéit à la main qui le conduit[Yes, the robot obeys the hand that guides it], performed by pupils at the Guigues elementary school.](/media/thumbs/7953/300x204-7953_guigues_4E.jpg)