Saint-Roch: Quebec City’s Urban Core is Reborn

par Lemoine, Réjean

Saint-Roch began its life as a working class quarter, the first outside Quebec City’s walls. For many years the most prosperous and populous part of the city, it was also home to much of the francophone community. From the mid 19th century to the late 1950s, Saint-Roch was Quebec City’s commercial, industrial and manufacturing centre. Today, with its rich architectural heritage and creative, resourceful population, Saint-Roch is the living legacy of four centuries of urban history, a testimony to the massive effort to save, restore, and bring new life to the city’s urban core.

Article disponible en français : Quartier Saint-Roch, la renaissance du coeur urbain de Québec

Downtown Transformed

Located in Quebec City’s lower town, Saint-Roch is separated from the upper town by the Cap Diamant escarpment and from the neighbourhood of Limoilou by the Saint-Charles River. To the east the Dufferin-Montmorency Autoroute, an artificial border, brutally cleaves Saint-Roch from the Old Port sector, its close neighbour until the 1960s. Langelier Boulevard, with its attractive tree-lined walkways, marks Saint-Roch’s western border with Saint-Sauveur, a residential neighbourhood.

Much of Quebec City’s population traces its roots back to Saint-Roch. So do many of the businesses that later relocated to other parts of the city and the surrounding region, Biscuits Leclerc being a prime example. By the 1970s Saint-Roch had fallen on hard times and was riddled with poverty and crime. But in the 1990s it began to rise from the ashes, reborn as a hip and creative neighbourhood, like so many other former working class and downtown districts in other Western cities. Students, artists and professionals began flocking to the area, drawn by Saint-Roch’s vibrant atmosphere. Whether they are aware of it or not, these new residents have been building on the neighbourhood’s traditional strengths: innovation, popular culture, socioeconomic diversity and entrepreneurship.

Saint-Roch: Four Centuries of History

People have lived in the area known as Saint-Roch since Quebec City’s colonial beginnings. Samuel de Champlain chose it as the site for Ludovica, the model city he one day hoped to build. The Recollect missionaries erected a convent on the banks of the Saint-Charles in 1620. In the late 17th century, under the auspices of the Augustinian Hospital Sisters, the convent became the city’s first General Hospital, a massive building that still stands not far from Parc Victoria. In 1692 the Recollects also built the Saint-Roch Hermitage, a small chapel on the site of the present day Dufferin-Montmorency overpass, as a place of devotion and retreat. Saint Roch, who lived in the Middle Ages during the black plague, was the patron saint invoked by city dwellers to protect against the influenza and smallpox epidemics common at the time. The neighbourhood and later the parish, founded in 1829, retained the name of this protector, who would be again invoked during the 18th century cholera epidemics and the 20th century Spanish flu.

At the end of the 18th century, urban development began along Saint-Vallier Street, then the start of the first road linking Quebec City and Montreal. It grew up around the Maison blanche, residence of Charles Aubert de la Chesnaye, the richest merchant in New France at the time. His house still stands at 870 Saint-Vallier Street East, between the Dufferin-Montmorency Autoroute and Comptoir Emmaüs, a large thrift store.

Saint-Roch grew swiftly in the early 19th century. Despite the swampy land and unhygienic living conditions, thousands of workers and craftsmen flocked to the area, attracted by the twenty-odd shipyards along the Saint-Charles River, which then employed some 3,000 workers. Irish immigrants also flooded into the neighbourhood during this period. With time, Saint-Roch became home to most of the city’s francophone residents while the English-speaking elite lived in the upper town.

The neighbourhood developed around Jacques Cartier Square, present day site of the Gabrielle Roy Library. In 1857 a covered market opened. The second floor of the market housed two halls for cultural events, one of which accommodated 500 people. Lectures were presented by learned societies, but the performing arts were by far the main attraction. They became a neighbourhood specialty, with Saint-Roch spawning theatre troupes, music halls, and, later, movie theatres. Saint-Roch’s cultural vocation developed even as the whole neighbourhood was rebuilding in the wake of the great fire of May, 1845, which destroyed 1,200 homes and left 12,000 people homeless.

As shipbuilding declined in the second half of the 19th century, Saint-Roch industrialized. Tanneries, potash plants and shoe factories sprung up in strategic locations throughout the district. Most of these businesses were owned by francophones, an unusual state of affairs at the time. One of them, Guillaume Bresse, built a mechanized shoe factory in 1864, a move that helped spark the creation of dozens of shoe and boot manufacturers clustered around Arago and Christophe-Colomb streets, an area still sometimes known as Îlot des tanneurs. The often harsh working conditions in the local factories led to the mobilization of hundreds of workers, many of them women, in the 20th century. Together, they founded the Catholic union movement, a forerunner of Quebec’s modern union movement and the Conféderation de Syndicats Nationaux (CSN) which still has offices in Saint-Roch. The parish clergy, at that time a particularly vital and powerful institution, played a key role in this chapter of local history.

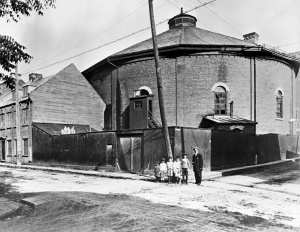

Saint-Roch’s golden age came

in the first half of the 20th century. During this period,

Saint-Roch and neighbouring Saint-Sauveur were home to two-thirds of Quebec City’s total population

and the vast majority of its francophone residents. Saint-Joseph Street, home to such big

department stores as Paquet, Laliberté, Pollack and Syndicat de Québec, reigned

as the city’s undisputed commercial centre. Electric tramways and train stations

brought thousands of people to local stores, cinemas, restaurants and theatres.

More than ever, Saint-Roch was the city’s hub of entertainment and popular

culture. One landmark venue was La Tour, built inside a former fuel reservoir.

This working class counterpart to Chez Gérard Cabaret was the city’s most

popular theatre from 1936 to 1965, with a capacity of 500 on two levels. La

Tour welcomed popular singers like La Poune and Juliette Huot, French stars

like Charles Trenet, American jazz bands, boxing and wrestling matches and even

cockfights.

Saint-Roch’s Decline

In Quebec City, as in most North American cities, the mid-fifties brought an exodus to newly-developed suburbs. Over three decades 100,000 people left the city’s older neighbourhoods for bungalows built on former farmland in Sainte Foy, Charlesbourg and Beauport. As Saint-Roch emptied out, the population plummeted from 20,000 to 5,000. The middle class abandoned the neighbourhood, leaving only the poor and the elderly behind.

In 1961 a study on housing in Quebec City concluded that

half of Saint-Roch’s housing stock was substandard and recommended a city-wide

operation to eradicate urban blight. The Commission split the city into urban

renovation zones. Saint-Roch was designated Area 10 and subdivided into two

zones: Zone 1 to the north of Charest

Boulevard and Zone 2 to the south. The commission

recommended demolishing all substandard residential and industrial buildings in

Saint-Roch while setting aside residential areas for senior citizens’ housing.

The era of expropriations and demolitions had begun.

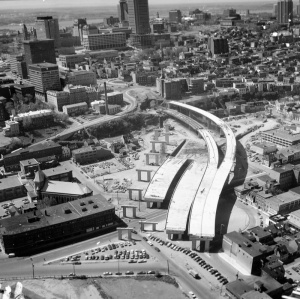

In the late 1960s the Laurentienne, Charest, and Dufferin highway projects

precipitated the unravelling of Saint-Roch’s urban fabric. The 1969

Dufferin-Montmorency Autoroute was especially devastating: to build it the city

demolished over 300 dwellings and 30 commercial buildings, expropriated the

property of over 200 families, and razed the entire parish of

Notre-Dame-de-la-Paix. The neighbourhood was split in two and severed from its

roots (the Saint-Roch Hermitage, the Maison Blanche, and Îlot des Palais), cut

off from the pillars of local nightlife (Chez Gérard cabaret, the Voûtes du

Palais, La Tour) and robbed of its traditional cultural diversity (a small Chinatown and a Jewish area with a synagogue).

To fight these demolitions and expropriations, the Area 10 Citizen’s Committee was formed in the mid-sixties by Monsignor Raymond Lavoie, priest of Saint-Roch parish. He also demanded that expropriated residents be relocated within the neighbourhood. Despite the Committee’s best efforts, however, many residents ended up being “deported” to distant parts of town, notably Place Bardy in the D’Estimeauville district. The deep scars left on both individuals and the neighbourhood as a whole took a long time to heal.

The late fifties also saw the construction of Quebec City’s first shopping malls—first Place Sainte Foy, then Place Laurier. Consumers stopped patronizing the big department stores on Saint-Joseph Street. Except for Laliberté, they all closed or went bankrupt in the 1970s. Saint-Roch’s industrial base was also shrinking fast as manufacturing businesses faltered one after another. The 1988 closure of the Dominion Corset factory marked the end of an era. Today, Rock City Tobacco is the last industrial concern still operating in Saint-Roch. By the late 1970s the neighbourhood was underpopulated and its storefronts boarded up. The Mail Centre-Ville, which converted a stretch of Saint-Joseph Street into a covered mall by adding walls and a roof, did little to help. The neighbourhood’s tallest and most prestigious structure, the Lafayette building, stood vacant.

Attempts at Urban Renewal

Between 1960 and 1980 municipal authorities tried repeatedly to halt Saint-Roch’s decline and get the neighbourhood back on its feet again. Their attempts often did more harm than good. In 1966 Mayor Gilles Lamontage (1965–1977) launched a project to rehabilitate the Saint-Charles River by encasing its heavily polluted banks in concrete. Another project known as Kabîr Kouba consisted of new housing built on abandoned industrial sites. Lamontagne also ordered the removal of railroad tracks along the river and in the rest of the neighbourhood and launched construction of the Mail Centre-Ville, an attempt to beat the large suburban malls at their own game. He even convinced Holiday Inn to open a hotel in the lower town in the hope of slowing the neighbourhood’s commercial decline.

The next mayor, Jean Pelletier (1977–1989), brought passenger trains back to Gare du Palais after a decade’s absence. He also had the Gabrielle Roy library built in 1982. But these projects alone weren’t enough to reverse the fortunes of a neighbourhood that had totally turned its back on its past.

La Grande-Place: “Renewal” Razes Everything in its Path

Most of these early urban renewal projects displayed a fundamental disregard for local history. Perhaps the worst of them all was the Grande-Place project, which epitomized everything that was wrong with the 1970s approach to renewal in Saint-Roch. The idea was to create a huge vacant space, stretching from the Dufferin overpass to de la Couronne Street, in the aim of launching a massive development project that would get the whole neighbourhood back on course. At the same time, plans were made to raze most of Îlot des tanneurs to build a highway along the escarpment between Langelier Boulevard and Côte d’Abraham. Two levels of government were involved in this plan; 500 people were displaced and nearly 200 buildings and homes demolished.

But neither the planned relocation of Collège F.-X.-Garneau nor the construction of a giant shopping mall came to pass. Opposition from citizens and businesses like Le Soleil, the daily broadsheet, proved too great. The 1973 Energy Crisis also led people to question the wisdom of major highway projects liable to permanently scar the neighbourhood. For 15 years, the project left a gaping hole in the city, an urban wasteland of dilapidated and boarded-up buildings nicknamed “Plywood City” with an open air “shooting gallery” at its centre.

Renewal

Mayor Jean-Paul L’Allier and his team took power in 1989 with a novel strategy to breathe new life into the neighbourhood. Culture and education would mend the urban fabric and make Saint-Roch vital again.

The city had come to understand the importance of considering the area’s history and character when planning renewal projects. For over ten years Saint-Roch was the focal point of municipal investment. Academics and researchers worked with the city on studies and consultations that used sociological, geographical, archaeological, historical and urban planning methodologies to better understand the neighbourhood. This research soon generated a substantial body of knowledge that highlighted Saint-Roch’s important legacy in the development of industry, trade, the arts, and the community movement in Quebec City.

Instead of building on the sprawling vacant lot of La Grande Place, the city first decided to reinforce the urban fabric around this “gaping wound.” First, the vacant Dominion Corset building was renovated and repurposed as La Fabrique, a new home for Université Laval’s faculty of visual arts. This brought more young people and a creative element to the neighbourhood. The City implemented a commercial revitalization program targeting Saint-Joseph, De La Couronne and Dorchester streets, with special funding to tear down Mail Centre-Ville and restore the newly visible façades of the historic buildings formerly obscured by the covered mall. Rather than demolishing the ageing heritage buildings on Côte d’Abraham, a city-funded restoration initiative helped set up an artists’ cooperative, Meduse. The F.X. Drolet. building, once a factory, was converted into a municipal workshop. A renovation subsidy program for former factories in the area around Arago and Christophe-Colomb streets facilitated the creation of over 150 artists’ lofts.

The 1993 decision to build a new public park on the site of La Grande Place was another milestone in Saint-Roch’s renewal. It put an end to the old dream of building a highway along the escarpment, a project that still had its proponents at City Hall and Quebec’s transport ministry. The new park built on and went further than an earlier endeavour at nearby Îlot Fleurie, a grassroots movement by residents who had taken over the area with art installations and guerrilla gardening. Jardin Saint-Roch embellished the neighbourhood, curbed the pervasive culture of petty crime and laid the groundwork for a number of real estate developments, including an Université du Québec campus and a hundred new housing units. In the early 2000s, after nearly 30 years of hard work, the gaping hole left by the Area 10 Zone 2 redevelopment project was finally filled. Urban life has returned this formerly barren space, given a new push with the arrival of new employers in the video games and Internet technology sectors.

At the same time, Saint-Roch has become increasingly aware of what it has to

offer tourists, with new hotels, upscale restaurants and walking tours. In 2009

Cirque du Soleil moved in with a free outdoor performance under the

Dufferin-Montmorency overpass in order to lure tourists from the Old Port

and Old Quebec.

Lingering Challenges

In 2011 Mayor Régis Labeaume’s administration is tackling a host of new projects: the Diamant theatre complex, brainchild of esteemed director Robert Lepage; residential development around the former public landfill near Point-aux-Lièvres; street furniture and public art design competitions; the tramway; and more. And several major challenges remain, from renovating the Gabrielle Roy library and Jaccques Cartier Square to turning the area under the Dufferin overpass into a viable pedestrian gateway to the Old Port and Old Quebec. For Saint-Roch to keep moving forward and continue enhancing quality of life in the neighbourhood, it will have to plan new residential developments, further boost business and nightlife, and calm traffic.

The rebirth of Saint-Roch has given Quebec City’s urban core a new lease on life and restored pride of place to its traditional “downtown.” Increasingly, locals and tourists alike are recognizing Saint-Roch as the place to go to get a sense of where the city is coming from—and where it is headed.

Réjean Lemoine

Historian, Urban Commentator

Additional DocumentsSome documents require an additional plugin to be consulted

Images

-

Ancien cimetière de S

Ancien cimetière de S

aint-Roch, util... -

Ancienne église Saint

Ancienne église Saint

-Roch, avant 19... -

Bénédiction de l'Égli

Bénédiction de l'Égli

se Saint-Roch, ... -

Cale sèche de la fond

Cale sèche de la fond

erie FX Drolet,...

-

Communauté chinoise d

Communauté chinoise d

e Québec, vers ... -

Consécration épiscopa

Consécration épiscopa

le de Mgr Garan... -

Construction de l'aut

Construction de l'aut

oroute Dufferin... -

Construction de la Bi

Construction de la Bi

bliothèque Gabr...

-

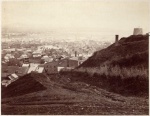

Côte d'Abraham, vers

Côte d'Abraham, vers

1900 -

Démolition de l'immeu

Démolition de l'immeu

ble qui abritai... -

Détournement de la Ri

Détournement de la Ri

vière Saint-Cha... -

Église Jacques-Cartie

Église Jacques-Cartie

r, vers 1880

-

Église Jacques-Cartie

Église Jacques-Cartie

r, vers 1880 -

Église Saint-Pierre e

Église Saint-Pierre e

t escalier Lépi... -

Église Saint-Roch, ve

Église Saint-Roch, ve

rs 1900 -

Employés de manufactu

Employés de manufactu

re

-

Escalier de la Chapel

Escalier de la Chapel

le (aujourd'hui... -

Escalier du Faubourg

Escalier du Faubourg

-

Escalier La Chapelle

Escalier La Chapelle

(actuellement a... -

Escalier Lépine

Escalier Lépine

-

Foule, spectacle en p

Foule, spectacle en p

lein-air Les Ch... -

Halle Jacques-Cartier

Halle Jacques-Cartier

, fin XIXe sièc... -

Incendie de juin 1845

Incendie de juin 1845

et ruines de l... -

Intérieur de l'Église

Intérieur de l'Église

Saint-Roch, ve...

-

La Tour, avant 1950

La Tour, avant 1950

-

Le mausolée de Zéphir

Le mausolée de Zéphir

in Paquet, comm... -

Magasin Laliberté, 18

Magasin Laliberté, 18

94 -

Magasin Laliberté, ve

Magasin Laliberté, ve

rs 1955

-

Magasin Paquet, vers

Magasin Paquet, vers

1920 -

Magasin Pollack, vers

Magasin Pollack, vers

1930 -

Magasin Pollack, vers

Magasin Pollack, vers

1950 -

Magasin Syndicat et P

Magasin Syndicat et P

lace Jacques-Ca...

-

Mail Saint-Roch

Mail Saint-Roch

-

Maison, rue des Commi

Maison, rue des Commi

ssaires, 1969 -

Palais Royal (actuel

Palais Royal (actuel

Théâtre Impéria... -

Parc Saint-Roch, dura

Parc Saint-Roch, dura

nt le Bivouac U...

-

Place Jacques-Cartier

Place Jacques-Cartier

, vers 1920 -

Procession, rue de la

Procession, rue de la

Couronne, Prem... -

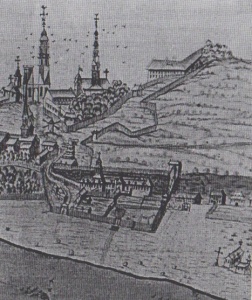

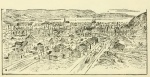

Québec vu du nord-oue

Québec vu du nord-oue

st (détail), 16... -

Rue de la Couronne, v

Rue de la Couronne, v

ers 1860

-

Rue Saint-Dominique,

Rue Saint-Dominique,

1972 -

Rue Saint-Joseph, ver

Rue Saint-Joseph, ver

s 1900 -

Saint-Roch et Saint-S

Saint-Roch et Saint-S

auveur après l'... -

Site des actuelles br

Site des actuelles br

etelles de l'Au...

-

Théâtre Princesse, Ru

Théâtre Princesse, Ru

e Saint-Joseph,... -

View of Quebec from G

View of Quebec from G

rant's Wharf, (... -

Vue de Saint-Sauveur

Vue de Saint-Sauveur

et Saint-Roch, ... -

vue du quartier Saint

vue du quartier Saint

-Roch, (vers 18...

Hyperliens

- Site promotionnel du quartier Saint-Roch

- Saint-Roch (Québec) - Wikipedia

- Rivière Saint-Charles - Wikipedia

Catégories

Bibliographie

Blanchet, Danielle. Les quartiers de Québec. Québec, 1987, « Saint-Roch : un quartier en constante mutation » 54 p.

Bluteau, Marc-André et. al., Les cordonniers artisans du cuir, Ottawa, Musée national de l’Homme. 1980, 154 p.

Bourque, Hélène. L’architecture domestique des faubourgs Saint-Jean et Saint-Roch avant 1845. Québec, IQRC, 199 p.

Duberger, Jean et Jacques Mathieu. Les ouvrières de la Dominion Corset à Québec 1886-1988. Québec, PUL, 1993, 148 p.

Gamache, Jean-Charles. Histoire de Saint-Roch de Québec et ses institutions. Québec, Charrier et Dugal, 1929, 335 p.

Lebel, Jean-Marie et Alain Roy. Québec 1900-2000. Le siècle d’une capitale. Québec, Multimondes, 2000, 157 p.

Lemieux, Frédéric. Gilles Lamontagne sur tous les fronts. Montréal, Del Busso éditeur, 2010, 688 p.

Morisset, Lucie K. La mémoire du paysage : histoire de la forme urbaine d’un centre-ville : Saint-Roch de Québec. Québec, PUL, 2001, 286 p.

Noppen, Luc et Lucie K. Morisset. Architecture de Saint-Roch. Guide de promenade. Québec, Ville de Québec, 2000, 139 p.