Forges du Saint-Maurice

par Trottier, Louise

The vestiges of the first ironworks in Canada, in operation from 1730 to 1883, have been preserved and are displayed at the Forges du Saint-Maurice National Historic Site, 15 kilometers north of Trois-Rivières. A commemorative plaque, laid at the site in 1923 by the Historic Sites and Monuments Board of Canada, indicates the early recognition of the historical importance to Canada of the Saint-Maurice Forges. Historical and archaeological research, begun in the sixties by the Quebec Ministry of Cultural Affairs and carried on since 1973 by Parks Canada, has uncovered the rich French contribution to this example of the region's industrial heritage. This research has shown that the complex was built using technology developed and employed in earlier forges in France.

Article disponible en français : Forges du Saint-Maurice

The Site of the Forges

The Forges du Saint-Maurice National Historic site is currently located on 23 hectares along a creek on the west bank of the Saint-Maurice River (NOTE 1). It consists of an expansive green park surrounding the remains of the Forges' production plant, living quarters and utility buildings. As well, the site offers a panoramic view of the Saint-Maurice River. The interpretation program established for the information and enjoyment of visitors includes exhibits and walking trails.

The Use of Natural Resources

In 1730, the King of France granted François Poulin de Francheville the right to mine the ore deposits on his Saint-Maurice seigneury. The granting of the royal warrant was the culmination of many requests for permission to use the mineral resources of New France that had been made by colonial authorities since the beginning of the 17th century. The acquisition of this right marked the beginning of Canada's iron and steel industry.

The Forges du Saint-Maurice were operated by more than fifteen companies in succession between 1730 and 1883. The first companies, established during the French Regime, had limited success (NOTE 2). Beginning in 1741, they were replaced by state enterprises, dependent first on the Crown of France and, later, on the British government. The Forges were operated by lessees from 1767 to 1846, at which time they were purchased by private manufacturing companies who ran them until their closure (NOTE 3).

At the time the warrant from the King of France was granted, it included three different areas. These were: the seigneury of Saint-Maurice and the seigneury of Saint-Etienne, where the actual Forges, including production plants, living quarters and utility buildings, were located, and Crown lands, where the mineral and forest resources needed for the industrial activities were found (NOTE 4). This was the territory used by the Forges for the entire period they were in operation.

The Beginning of Iron Production

When the ironmasters from Burgundy, Champagne and Franche-Comté constructed the industrial components of the Forges du Saint-Maurice plant, they used technological innovations that had been developed from the mid-15th to the 17th century in their native regions of France. The most significant innovation was a two-step indirect ore reduction process: the ore was first transformed into cast iron in a blast furnace, fired by plant-based fuel, and then fined into bars in the forge (NOTE5).

A blast furnace and two forges were built between 1736 and 1740, on a gully at the mouth of the Saint Maurice Creek, which provided hydraulic power (NOTE 6). The pyramid-shaped blast furnace was about 9 meters tall, fuelled by charcoal and run by a water wheel, 10 meters in diameter, located in the adjacent waterway. Built on masonry foundations, the complex included areas for the storage of raw materials and cast iron, work areas for founders and moulders, as well as a charging platform and a vault for the nozzles and the bellows (NOTE 7).

To increase production, the blast furnace was rebuilt in 1854 and underwent other modifications at the beginning of the 1880s. The remains of the foundation of the bellows chamber, a gas recovery system, a moulding floor, a tailrace, as well as a turbine room and a circular brick crucible, provide evidence of these changes.

Built in 1736 and rebuilt, after a fire, in 1747, the lower forge used the renardière process of fining (NOTE 8). A tall chimney, nearly 14 meters in height, was the building's distinguishing feature. Archival documents, together with the structures uncovered in archaeological digs, such as masonry foundations, chaferies, a tilt hammer (NOTE 9) and a hydraulic turbine caisson, attest to changes made during the 19th century. The building was abandoned in 1870 and converted to the manufacture of axes in 1872.

The upper forge was built in 1739 and the remains of the base of its chimney, its hurst frame and the foundations of its bellows have been excavated. Evidence of changes made between 1854 and 1880 is provided by the remnants of the crucible of a second blast furnace, the base of a steam engine, as well as a hydraulic turbine (NOTE 10).

Although technical innovations were introduced in the 19th century, the blast furnace, the upper forge and the lower forge retained their original features until the establishment closed.

Through archaeological digs and archival documents, researchers have been able to uncover, date and determine the function of several outbuildings. These were complementary to the production workshops and appear to date from the 19th century. They include the brick kilns used to make charcoal, sheds, a blacksmith shop, a finishing shop for assembling cast iron parts, as well as a lime kiln and a saw mill (NOTE 11).

Until about 1846, the Forges produced iron bars and consumer goods, such as kitchen stoves and accessories, kettles, nails, anvils, as well as ploughshares, wagons and train wheels, saw mill parts, and artillery pieces and ammunition. After 1850, the company's main product was pig iron for major foundries in Trois-Rivières and Montreal (NOTE 12). The movement of goods and resources, as well as the regional distribution of products manufactured at the forges, led to the development of a transportation network. Because of the proximity of the Saint-Maurice River, raw material, machinery parts and consumer goods were transported to Trois-Rivières first by canoe, then by bateaux or flat-bottomed boats, on barques, as well as by ferry to Cap-de-la-Madeleine on the other side of the Saint-Maurice River, and later, in the 19th century, by steam boat. Roads were gradually built and improved over the 18th and 19th centuries, linking the Forges to Trois-Rivières and to the regions around Montreal and Quebec, with goods transported by horse-drawn vehicles.

The Industrial Community

Over the years it was in operation, the Forges du Saint-Maurice became a real community, characterized by a close relationship between work and domestic activities. Historical and archaeological research has revealed much about daily life at the Forges (NOTE13). The remains of dwellings show that the majority of workers and administrators lived in close proximity to the production plant. Evidence has also been found both of small houses and tenement houses, dating from the end of the 18th century, some accommodating a single family, others, a number of families or groups of specialized workers.

Built in 1737-1738, the Grande Maison was first a residence, then an administrative and sales centre. When the company ceased operations and people began to move away from the Forges, it was gradually demolished (NOTE 14). The main outbuildings were barns, a bakery, stables, warehouses, toilets and a chapel.

Workforce

In 1842, the population of the Forges du Saint-Maurice was 425, made up mainly of those working at the blast furnace and the forges, in the warehouses, in mining and timber trades, in road construction, and in the transportation of goods.

Beginning in the second half of the 19th century, a number of these tradesmen went to work in similar establishments in the Mauricie region, notably in the Radnor, L'Islet, Saint-Tite and Saint-Boniface foundries. Some moulders, a certain number of them of British origin, went on to practice their skills in rural foundries in neighbouring regions or in major ironworks in Montreal (NOTE 15).

A Changing Heritage

At the end of the 1970s, the Forges du Saint-Maurice National Historic Site continued to be one of the largest archaeological dig sites in Canada. The conservation and display of this site, with a history spanning 150 years, presented many challenges: remains from the French Regime had almost completely disappeared; there were several layers of occupation of industrial structures and other buildings one on top of the other; gaps were evident in historical documentation and not all documents were of the same quality. This made it difficult, and perhaps unrealistic, to opt for either the complete reconstruction of all buildings or the selection of the technology or the community of single era when developing an interpretation program.

In these circumstances, a forum of experts, including archaeologists, architects, historians, managers and interpretive guides from the site, chose to focus on the evolution of industrial activities at the Forges and the community that participated in their growth, while ensuring that the site blended into the surrounding natural environment. These experts recommended an interpretation program based on new practices in historical and industrial archaeology and on innovative trends in contemporary architecture.

Accordingly, some structures, such as the lower forge, are preserved in situ. An architectural competition was held and a proposal selected for the site: the erection of "symbolic structures" over a model of the last blast furnace. These modular concrete and steel structures serve both to preserve the remains of the historic complex and to explain the movement of the huge water wheel, the functions of the adjacent buildings, and the process used to produce cast iron. This design for the display of the blast furnace complex received the award of excellence of the Ordre des architectes du Québec in 1985 (NOTE 16).

Below this monumental work, a path runs alongside the Saint-Maurice Creek, leading to what remains of the upper forge and two mills. The ruins of the lower forge can be identified near the Saint-Maurice River by the stone chimney. The complex includes an amphitheatre where the iron-making process is demonstrated to visitors to the site.

Displaying the Collections

The Grande Maison has been rebuilt and serves as a visitors' centre where the extensive Parks Canada archaeological and ethnological collections, made up largely of articles manufactured at the Forges, are displayed in thematic exhibits. For example, domestic articles related to cooking, heating, farming activities and sports are presented in the exhibit, The Forges and the Colony. The exhibit, The Forges and Industry, displays iron wagon wheels and other artefacts associated with technological innovations of the last twenty years of the establishment's operation. There is also a light and sound show that brings to life a large model of the Forges complex in 1845. Based on historical and archaeological research, the purpose of this museographical component is to help visitors understand the functions and the evolution of the industrial operations and of daily life in the community during this period (NOTE 17).

The Continuing Legacy of the Forges du Saint-Maurice

Since the late 1970s, numerous publications resulting from the research, conservation and interpretation program of the Forges du Saint Maurice National Historic Site have been added to earlier published documents on the "Old Forges" by Quebec historians and writers (NOTE 18). The examples these works provide of the various techniques used in the industrial processes and of the material culture associated with the trades and the industrial community confirm that the Forges du Saint-Maurice are central to Canada's industrial heritage (NOTE 19).

This documentation, together with the site's rich archaeological and ethnological collections and interpretation programs, provide the means of ensuring that the memory of this early period of industrial society in Canada will endure.

Louise

Trottier

Historian and Museologist

Museum Research Consultant

NOTES

1. These are the site boundaries set by the Historic Sites and Monuments Board of Canada. "This site refers to the 56-acre industrial complex as surveyed for its sale by the government in 1845 and as shown on the 1846 survey" [Translation]. Mauricie Field Unit, Commemorative Integrity Statement: Forges du Saint-Maurice National Historic Site of Canada, 2003. Unpublished document.

2. In spite of the talent and enthusiasm of the first ironmaster, Pierre-François Olivier de Vézin, a native of the Champagne region in France, several factors hampered progress on the project, notably, a poor understanding of the site on which the plant was situated, technical problems related to estimates of the potential of the stream and to the construction of the industrial structures, discord among the business partners, and a lack of qualified workers. The Forges began producing iron for the royal navy in 1738.

3. Réal Boissonneault, Les Forges du Saint-Maurice, 1729-1883, 150 ans d'occupation et d'exploitation, Booklet No. 1, Forges du Saint-Maurice National Historic Site, 1983.

4. Michel Bédard, Utilisation et commémoration du site des Forges du Saint- Maurice(1883-1963), Parks Canada, Manuscript Report No. 357, 1979, p. 26.

5. Serge Benoît, « La consommation du combustible végétal et l'évolution des systèmes techniques », Denis Woronoff, Forges et Forêts. Recherche sur la consommation proto-industrielle du bois, Paris, Éditions de l'École des Hautes Études en sciences sociales, 1990, p. 89-150.

6. This creek is now called Washery Creek because its source is near an artificial pond formed by a dam where the washery used for cleaning the ore was located. The creek was used by the industrial complex to provide the hydraulic power needed for its operations. Pierre Cloutier, Claire Desmeules et Pierre Drouin, Lieu Historique National des Forges du Saint-Maurice, Inventaire des ressources culturelles, Québec, Parks Canada, 2003, p. 1-10.

7. Roch Samson, The Forges du Saint-Maurice. Beginnings of the Iron and Steel Industry in Canada 1730 - 1883, Québec, Les Presses de l'université Laval and Canadian Heritage, 1998, pp.143-161.

8. The renardière is a hearth used both to heat and to purify the cast iron so that it can then be fined. See Samson, op. cit., p.168-172. This type of hearth was used in France in the 16th and 17th centuries, particularly in the Champagne, Lorraine and Franche-Comté regions.

9. The tilt hammer is a small hydraulic hammer with quick-stroke action used to forge small iron.

10. Pierre Cloutier, Claire Desmeules and Pierre Drouin, op. cit., p. 10-25.

11. Pierre Drouin and Alain Rainville, L'organisation spatiale aux Forges du Saint-Maurice, Typescript, Québec, Parcs Canada, 1980.

12. Johanne Cloutier, Répertoire des produits fabriqués aux Forges du Saint-Maurice, Unpublished Report no 350, Ottawa, Parcs Canada, 1980.

13. Fragments of pottery, clay pipes, glass, utensils, stoves and hearths were used to determine the layout of the dwellings, the location of furniture, lighting, heating, as well as where meals and leisure activities took place. Luce Vermette, La vie domestique aux Forges du Saint-Maurice, Ottawa, Parks Canada, 1982, Histoire et Archéologie no 58.

14. Jean Bélisle, La Grande Maison des Forges du Saint-Maurice, témoin de l'intégration des fonctions, étude structurale, Manuscript Report No. 272, Ottawa, Parks Canada, 1977.

15. Peter Bishoff, « Des Forges du Saint-Maurice aux fonderies de Montréal : mobilité géographique, solidarité communautaire et action syndicale des mouleurs, 1829-1881 », Revue d'histoire de l'Amérique française, n° 43, 1, 1989, p. 3-29; Louise Trottier, « La Fonderie Trottier de Saint-Casimir : la contribution des entreprises rurales au patrimoine industriel du Québec », Le Cageux, 2,3, Automne 1999, p. 22-27.

16. André Bérubé, « National Report for Canada 1984-1987 », Transactions 1, Vienna, Federal Office for the Protection of Monuments, and the Department of the Technical University of Vienna, Under the auspices of the International Committee for the Conservation of the Industrial Heritage, 1987, p. 20-31.

17. Pierre Cloutier, Claire Desmeules and Pierre Drouin, op. cit., p. 74.

18. Louise Trottier, Les Forges : Historiographie des Forges du Saint-Maurice, Montréal, Boréal Express, 1980, 180 p.

19. On the multi-disciplinary approach and methodology associated with the study and display of industrial heritage, see Louise Trottier, Le patrimoine industriel au Québec, Québec, Direction générale des publications gouvernementales, 1985, 85 p. Louise Trottier (dir.) From Industry to Industrial Heritage/De l'industrie au patrimoine industriel, Proceedings of the Ninth International Conference of the Industrial Heritage/Actes du IXe congrès international sur la conservation du patrimoine industriel, Ottawa, Canada Science and Technology Museum, 1998.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Bédard, Michel, Utilisation et commémoration du site des Forges du Saint-Maurice (1883-1963), Parcs Canada, Travail inédit no 357, 1979.

Bélisle, Jean La Grande Maison des Forges du Saint-Maurice, témoin de l'intégration des fonctions, étude structurale, Travail inédit no 272, Ottawa, Parcs Canada, 1977.

Bishoff, Peter, « Des Forges du Saint-Maurice aux fonderies de Montréal : mobilité géographique, solidarité communautaire et action syndicale des mouleurs, 1829-1881 », Revue d'histoire de l'Amérique française, n° 43, 1, 1989, p. 3-29.

Boissonneault, Réal, Les Forges du Saint-Maurice, 1729-1883, 150 ans d'occupation et d'exploitation, Cahier no 1, Parc historique national des Forges du Saint-Maurice, 1983.

Cloutier, Johanne, Répertoire des produits fabriqués aux Forges du Saint-Maurice, Travail inédit no 350, Ottawa, Parcs Canada, 1980.

Cloutier, Pierre , Claire Desmeules et Pierre Drouin, LieuHistorique National des Forges du Saint-Maurice, Inventaire des ressources culturelles, Québec, Parcs Canada, 2003, 84 p.

Drouin, Pierre et Alain Rainville, L'organisation spatiale aux Forges du Saint-Maurice, document manuscrit, Québec, Parcs Canada, 1980.

Parcs Canada, Unité de Gestion de la Mauricie, Énoncé d'intégrité commémorative, Lieu historique national du Canada des Forges-du-Saint-Maurice (Trois-Rivières, Québec), Document inédit, 2003.

Samson, Roch, Les forges du Saint-Maurice. Les débuts de l'industrie sidérurgique au Canada 1730 - 1883. Québec, Les Presses de l'université Laval et ministère du Patrimoine canadien, 1998, 460 p.

Trottier, Louise « La Fonderie Trottier deSaint-Casimir : la contribution des entreprises rurales au patrimoine industriel du Québec », Le Cageux, 2,3, Automne 1999, p. 22-27.

Le patrimoine industriel au Québec, Québec, Direction générale des publications gouvernementales, 1985. 8 5p.

Les Forges : Historiographie des Forges du Saint-Maurice, Montréal, Boréal Express, 1980, 180 p.

Trottier, Louise (dir.), From Industry to Industrial Heritage/De l'industrie au patrimoine industriel, Proceedings of the Ninth International Conference of the Industrial Heritage/Actes du IXe congrès international sur la conservation du patrimoine industriel, Ottawa, Musée national des Sciences et de la Technologie, 1998.

Vermette, Luce, La vie domestique aux Forges du Saint-Maurice, Ottawa, Parcs Canada, 1982, Histoire et Archéologie, no58.

Additional DocumentsSome documents require an additional plugin to be consulted

Images

-

Couverture du livre «

Couverture du livre «

Les Forges du S... -

Couverture du livre «

Couverture du livre «

Les Forges du S... -

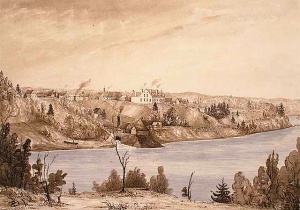

Forges de M. Bell sur

Forges de M. Bell sur

la rivière Sa... -

Forges du Saint-Mauri

Forges du Saint-Mauri

ce, 1919

-

Forges du Saint-Mauri

Forges du Saint-Mauri

ce, Trois-Rivie... -

Grande-Maison, Forges

Grande-Maison, Forges

du Saint-Mauri... -

La maison des Forges,

La maison des Forges,

Trois-Rivière... -

Les Forges du Saint-M

Les Forges du Saint-M

aurice, 1886

-

Les Forges du Saint-M

Les Forges du Saint-M

aurice, Trois-R... -

Les Forges du St-Maur

Les Forges du St-Maur

ice, 2009 -

Les Forges du St-Maur

Les Forges du St-Maur

ice, 2009 -

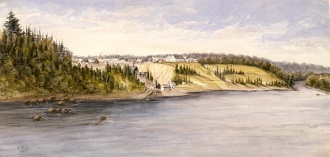

Les forges, rivière

Les forges, rivière

Saint-Maurice, ...

-

Les vieilles forges d

Les vieilles forges d

u Saint-Maurice... -

Plaque commémorative

Plaque commémorative

des Forges du S... -

Timbre commémoratif «

Timbre commémoratif «

Les Forges du S... -

Vase et fragments d'a

Vase et fragments d'a

ntiquité trouv...

-

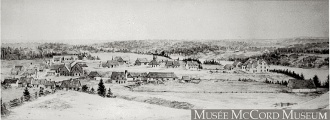

Vue à vol d'oiseau d

Vue à vol d'oiseau d

e Trois-Rivièr... -

Vue intérieure du ki

Vue intérieure du ki

osque "au lieu ... -

Vue panoramique des F

Vue panoramique des F

orges du Saint-... -

Vue rapprochée de la

Vue rapprochée de la

roue à aubes, L...

Document sonore

Document PDF

Hyperliens

- Forges du Saint-Maurice National Historic Site of Canada

- Mining History Centre of Lewarde

- Itinéraires européens du patrimoine industriel

- Musée des techniques et cultures comtoises

- The Ironbridge Gorge Museums

- Canadian Industrial Heritage

- TICCIH, The International Committee for the Conservation of the Industrial Heritage