Jacques Cartier

par Portes, Jacques

Jacques Cartier was among a group of explorers who left Spain, Portugal, England and France in the 16th and 17th centuries, mainly in search of a passage towards the elusive and mythical China. Cartier became one of the "discoverers" of the New World, an immense pair of continents now called the Americas, which blocked the path of all the navigators to the Far East. He was a meticulous explorer who mapped out a vast territory extending from the Gulf of St. Lawrence to the village of Hochelaga (present-day Montreal), all of which he claimed for the King of France. Cartier did not however manage to found a permanent colony. During the 19th century, the first historians of French Canada proclaimed Jacques Cartier the discoverer of Canada, for the idea of a French discoverer served the emerging nationalist interests very well indeed.

Article disponible en français : Jacques Cartier

The Early Days

The historical facts concerning Jacques Cartier, renowned sailor from Saint-Malo, are now well established, but they do not always tally with how he is depicted in popular history. Like the other European kings, Francis I (1494-1547) was searching the Americas for a passage to the elusive, mythical Orient. Giovanni da Verrazano had failed in this quest, so Jean Le Veneur, Grand Almoner of France and Abbot of Mont Saint-Michel, advised his king, who was then on a pilgrimage, to entrust a new expedition to one of the members of his family. That relative was the very experienced Saint-Malo sailor, Jacques Cartier. Born in 1491 near Saint-Malo, in the family's ancestral home in Limoëlou (a name subsequently given to a borough of Quebec City), Cartier had already had experience exploring the Americas. Shortly after becoming a captain, Cartier had participated in expeditions exploring the coast of South America, particularly near present-day Brazil. He had also encountered some the fishemermen who plied their trade off the Grand Banks of Newfoundland. Thus, he was well prepared for the expedition in search of the coveted Northwest Passage that would supposedly lead to China.(NOTE 1)

The First Voyage

On April 20, 1534, two tiny ships, the Triton and the Goéland, left Saint-Malo with Jacques Cartier at the helm and a crew of 61 men. He reached Newfoundland in less than three weeks, making record time. After proceeding through the Strait of Belle Isle, he explored the Gulf of St. Lawrence. In Chaleur Bay, Jacques Cartier made initial contact with the Micmacs, but he seemed disappointed with the Natives-whom he distrusted-and who had only skins to offer (such merchandise was little valued at the time). Sailing farther north, the expedition discovered Gaspé Bay where 200 Iroquoian people from the region of Stadacona (present-day Quebec City) were fishing.

To Cartier, these Amerindians seemed impoverished, without any apparent riches. As a way of asserting the power of his king, the Saint-Malo sailor had an immense wooden cross adorned with the royal Fleur-de-Lys crest erected at Gaspé on July 24th 1534. Then he laid a trap for the Native chief, Donnacona, by inviting him aboard in order to seize his sons, whom he took to France without leaving two of his own men behind in exchange, as custom normally would have had it. The two ships left Gaspé for Anticosti Island. It was there that Jacques Cartier saw the St. Lawrence estuary open up before his eyes, giving the clear impression of a mighty body of water penetrating the heart of the continent. On September 5th, 1534, the little expedition docked back in Saint-Malo without any convincing results to show for their efforts. Nevertheless, when the two Iroquoian hostages were given audience with the king, their apprearance caused a stir, thus kindling imaginations, evoking the fabulous kingdom of the Saguenay and creating a new incentive for another exploratory expedition. The presence of the Natives revived old questions and inspired new ones: Was there really a passage to China? Were there really cartloads of gold to be had in the Saguenay?

The Second Voyage

Jacques Cartier's second voyage was more ambitious and more fruitful than the first. The expedition included three ships (the Grande Hermine, the Petite Hermine and the Émerillon), about 100 men, and provisions for 15 months-enough for the expected winter in the New World. They left Saint-Malo on May 19th, 1535, but did not reach Anticosti before August. When the crew arrived in Stadacona (present-day Quebec City), the Native chief, Donnacona, was delighted to be reunited with his sons, but he did not appreciate the fact that the French had built a fort outside his village, nor that they had ventured as far as Hochelaga (present-day Montreal) to meet with rival tribes. Upon arrival at the future site of Montreal, Jacques Cartier realized that any further navigation was blocked by the Lachine Rapids, but also that the valley seemed suitable for settlement. The winter at Stadacona was particularly difficult: there were Natives prowling about the vicinity and, most of all, scurvy was ravaging the expedition. Twenty-five men eventually succumbed to it quickly before the Natives provided the group with life-giving herbal teas and fresh produce. On May 3rd, 1536, Jacques Cartier once again seized about 10 or so hostages, including Donnacona and his sons, and set sail for Saint-Malo, without having been able to explore the Saguenay or uncover any real evidence of the region's riches. He nevertheless planned to colonize this promising new land.

The Third Voyage

Jacques Cartier did not return to the St. Lawrence Valley until five years later, after a great deal of hesitation on the part of the king. This time he was no more than the pilot for a full-fledged colonization expedition led by Jean-François de La Rocque, Lord of Roberval, who was to lead over 500 men on a fleet of 10 ships. Too impatient to await departure, Jacques Cartier, raised sail early and left on May 23, 1541, taking with him half of the expedition's crew. Once he reached Newfoundland, with his superior nowhere in sight, he proceeded alone to Stadacona. The Saint-Malo sailor lied to Chief Agona concerning the fate of the Natives he had brought with him to France during the previous voyage-for they had all died. Then he visited Hochelaga again, only to conclude once and for all that the much-vaunted passage to China simply did not exist. Wintering was made even more difficult than on the previous occasion by the hostility of the Natives, who harassed the French. But hope returned with the discovery of "diamond-like stones, the most beautiful and of the highest quality lustre and cut that one might ever see." Jacques Cartier decided to return at once to Saint-Malo with his treasure. Thus, in June of 1542, when he finally met up with Roberval in the Gulf of St. Lawrence, the navigator refused to return to Stadacona with his superior. And so Roberval had to go on alone, but he failed miserably in his attempt at colonization, before being forced to return to Saint-Malo the following summer. As for Cartier's diamonds, they proved to be nothing more than iron pyrite (fool's gold), having no value whatsoever.

Jacques Cartier, whom Viscount de Chateaubriand described in his writings as the "French Christopher Columbus," never returned to Canada again. Saddled with financial problems, given the meagre profits he had made from his expeditions, he had no chance of being entrusted with any further expeditions by the king, who had expressed his great disappointment with Cartier's discoveries. Accompanied by his wife Catherine, with whom he had no children, he retired to his Limoëlou manor. Cartier spent the rest of his life offering occasional navigation advice and sifting through memories of his travels before dying of plague in 1557.

What Did Cartier Really Achieve?

Jacques Cartier's successive voyages bore very little immediate fruit. His objectives were commercial in nature and were not fully achieved. His strategic mission also ended in failure and he never sought to convert the Amerindians (whom he considered "savages," to Christianity), even though he developed a 54-word lexicon in order to communicate with them. As for the Amerindians whom he brought to France, they all died prematurely of disease. Over 60 years went by until the French once again ventured up the St. Lawrence with Samuel de Champlain to found Québec City in 1608. The main achievement of Jacques Cartier was that, as a meticulous explorer, he mapped out the region, thereby providing those that would follow a better understanding of the region. He also contributed considerably to the place names of the region, giving names to places we know to day such as the Fleuve Saint-Laurent [St. Lawrence River], the Chute Montmorency [Falls], Île aux Coudres, La Malbaie, and Havre Sainte-Catherine [Harbour]. Moreover, to a large extent,16th-century cartography took its inspiration from his writings.

As opposed to Champlain or Frontenac, who established and defended New France with a flair, Jacques Cartier could have been forgotten entirely. However, such was not the casd, as the awakening of nationalism in Canada (as well as in Quebec) brought the Saint-Malo sailor back to the centre stage of Canadian history.

The Return of the Saint-Malo Sailor

During the 19th century, the name Jacques Cartier was rarely mentioned in France, where he had become nothing more than a remote historical footnote.

On the other hand, in Canada, the Saint-Malo sailor was re-invented and promoted as French Canada's first national hero, as such a key historical figure could conveniently be used during national events to promote the Catholic faith or the province's historical connection with France. The creation of a monument for commemorating Jacques Cartier was considered as early as 1835, and George Barthélemy Faribault published Cartier's diary, which was republished a few years later with a portrait of the navigator. As early as 1850, Quebec began to appropriate Cartier as a national historical figure by giving his name to several locations throughout the province. As a result, a market and several streets in Montreal and Quebec City were named in his honour. The exploits of the discoverer of Canada were lauded and he was given a place in the nation's history equal to that of Champlain. Although the 350th anniversary of his first voyage was not celebrated in 1884, a commemorative monument was erected in Quebec City in 1889.

In Jacques Cartier, the Canadian Confederation proponents saw a likely national hero who had no identifiably precise historical role and who could satisfy both Canadian communities' [English and French-speaking] desire for a central historical figure. Little by little, Cartier was invested with this role. He became the incontestably French "discoverer" of the majoritarily English-speaking Canada. In 1905, the first representatives of Canada to France persuaded the French Government to erect a statue of Jacques Cartier on the ramparts of the town of Saint-Malo. Then, in marked contrast to the uncelebrated 350th anniversary of 1884, in 1934, large-scale events were organised in both France and Canada to mark the 400th anniversary of the first voyage of the Limoëlou navigator. And so, both France and the Province of Quebec joined in the celebrations.(NOTE 2) The 400th anniversary initiative was the result of a 1929 appeal made by Rodolphe Lemieux, a member of parliament from the Quebec riding of Gaspé. Lemieux's idea was quickly taken up by Senator Raoul Dandurand, a member of the Association France-Amérique, as well as by Quebec's Catholic and nationalist associations (the Action Sociale Catholique and the Société Saint-Jean-Baptiste). The movement also had the full-fledged support of the daily newspaper, Le Devoir. It was a particularly Quebec-based French Canadian initiative, as the federal government and English-speaking Canadians stayed out of the picture. French involvement came from the Association France-Amérique, which requested and obtained the support of the French government. And so a national committee chaired by Gabriel Hanotaux, a former French diplomat and academician, was created.

Because of the possibly precarious nature of the situation, the French took precautions in order to forestall the development of any suspicions from Ottawa. For example, the French chose to give the miniature replica of the Grande Hermine to the federal government, rather than to the Government of Quebec. The Catholic Church's fears concerning the secular, republican influence of France also had to be dealt with. And so two religious figures were sent with France's official delegation. All the festivities unfolded without the slightest hitch. Early in July 1934, in order to commemorate its historical connection with New France, the town of Saint-Malo extended a pleasant but relatively subdued welcome to the Canadian delegation. The 200 members of France's official delegation to Canada - who arrived on the ocean liner, the Champlain, escorted by three warships - were received with a great deal more enthusiasm.

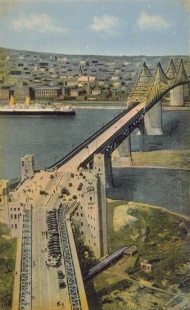

During the festivities held on August 24-26 in the Gaspé, over 30,000 people attended the unveiling of a large granite cross from Saint-Malo. The Gaspé event was followed by celebrations in Quebec City, Trois-Rivières and Montreal that were met with resounding success. The festivities reached a climax on the 1st of September with the inauguration of the Jacques Cartier Bridge in Montreal. The speeches given by the French delegates aroused the admiration of columnists: "The French empire as imagined by French people of the 17th century never materialized. Nevertheless, something more important remains; more than the glorious vestiges of the empire and more than the French place names scattered across the entire continent. For in spite of all the hindrances that have hampered the efforts of the French people and slowed their growth, they remain ever faithful to the language and faith of their ancestors."(NOTE 3) The French were moved by the warm welcome that they received in the Province of Quebec, which contrasted starkly with the subsequent visits to Ottawa and Toronto that were greeted with near indifference.

The celebrations took on a distinctly religious tone, an indication of how the historic person of Jacques Cartier was being altered and used as a political instrument. For historical accounts reveal that religion was far from Cartier's primary motive for contacting the Native peoples. In 1984, it was clear that the federal government had appropriated Jacques Cartier as a national historic figure, as Pierre Elliott Trudeau's Ottawa government was seeking to build a strong Canadian national identity, in order to counter the rise of Quebec nationalism. This explains why the funding for the renovation of Jacques Cartier's manor in Limoëlou came from a Canadian foundation and why the federal government invested in the project. In 2006, with similar intentions in mind, the Government of Quebec took advantage of the discovery of the site of Roberval's settlement in Cap-Rouge (1541-42), in order to carry out its own appropriation of Jacques Cartier. It invested a considerable sum ($7 million) in developing the site, which is the oldest European settlement in North America. Thus, an expedition that was a bitter failure in its own time has today been bestowed with an aura of honour and glory. And so, as the result of the labours of a Saint-Malo sailor, Quebec has been able to discover more of its pioneer roots, thereby asserting its claim on the continent and affirming its North American identity.

The successive movements to appropriate Jacques Cartier as a national historic figure (by the Province of Quebec in 1835, 1934 and 2006 and by the Government of Canada in 1984) merely reflect a desire to make convenient use of the historical facts that best serve the ever-changing interests of various levels of government. The Saint-Malo navigator would probably have not understood this strange manner of interpreting the events surrounding his voyages to the New World-especially since his contemporaries did not see his activities in such a positive light-yet his name will always remain linked with that of Canada.

Jacques Portes

Professor, Université de Paris-VIII, Saint-Denis

NOTES

Note 1: Gilles Havard and Cécile Vidal, Histoire de l'Amérique française (Paris: Flammarion, 2003), pp. 22-27.

Note 2: The following information was taken from an article by Jacques Portes, "1934: le 400e anniversaire du voyage de Jacques Cartier en perspective", Études canadiennes - Canadian Studies, 17 décembre, 1984, pp. 207-213.

Note 3: Homer Héroux, Le Devoir, August 30, 1934. [Original citation translated into English]

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Braudel, Fernand (dir.), Le monde de Jacques Cartier : L'aventure au XVIe siècle, Montréal, Libre Expression, and Paris, Berger-Levrault, 1984, 326 p.

Havard, Gilles, et Cécile Vidal, Histoire de l'Amérique française, Paris, Flammarion, 2003.

Litalien, Raymonde, Les explorateurs de l'Amérique du Nord, 1492-1795, Sillery, Les éditions du Septentrion, 1993.

Portes, Jacques, « 1934 : le 400e anniversaire du voyage de Jacques Cartier en perspective », Études canadiennes - Canadian Studies, 17, December 1984.

Additional DocumentsSome documents require an additional plugin to be consulted

Images

-

Défilé historique: Ja

Défilé historique: Ja

cques Cartier e... -

Intérieur de la maiso

n de Jacques Ca... -

Jacques Cartier

-

Jacques Cartier dress

Jacques Cartier dress

e une croix, Qu...

-

Jacques Cartier monum

Jacques Cartier monum

ent overlooking... -

Jacques Cartier racon

Jacques Cartier racon

tant le récit d... -

Jacques Cartier renco

ntre les Indien... -

Jacques Cartier sur l

Jacques Cartier sur l

e mont Royal, v...

-

Jacques Cartier. phot

Jacques Cartier. phot

ographie d'une ... -

L' arrivée de Jacques

L' arrivée de Jacques

Cartier à Hoch... -

L'arrivée de Jacques

Cartier à Québe... -

La place Jacques-Cart

ier et le vieil...

-

La place Jacques-Cart

ier, à Montréal... -

La signature de Jacqu

La signature de Jacqu

es Cartier -

Le drapeau national "

Le drapeau national "

Jacques Cartier... -

Monument Cartier-Bréb

Monument Cartier-Bréb

euf [Vers 1890]...

-

Pont Jacques Cartier

Pont Jacques Cartier

Bridge, Montréa... -

Québec. 1908. Jacques

Québec. 1908. Jacques

Cartier & Donn... -

Statue de Jacques Car

Statue de Jacques Car

tier à Montréal... -

Tricentenaire de Québ

Tricentenaire de Québ

ec 1908. Jacque...

Vidéo

Document sonore

Documents PDF

-

Arrivée de Cartier à Hochelaga en 1535

Arrivée de Cartier à Hochelaga en 1535

-

Aux grandes fêtes de Gaspé, une croix colossale est dévoilée

Aux grandes fêtes de Gaspé, une croix colossale est dévoilée

-

Extrait décrivant les Amérindiens de l'archipel de Blanc-Sablon en 1534

Extrait décrivant les Amérindiens de l'archipel de Blanc-Sablon en 1534

-

Extrait racontant la plantation d'une croix à Gaspé en 1534

Extrait racontant la plantation d'une croix à Gaspé en 1534

-

Le dévoilement du buste de Jacques Cartier

Le dévoilement du buste de Jacques Cartier

-

Le lexique dressé par Jacques Cartier en 1534

Le lexique dressé par Jacques Cartier en 1534

-

Maladie lors de l'hivernement de 1535

Maladie lors de l'hivernement de 1535

-

Un monument éternel à la mémoire de Cartier

Un monument éternel à la mémoire de Cartier