Anticosti National Park

par Brisson, Geneviève

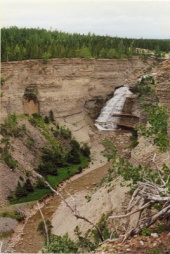

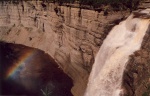

With the creation of Anticosti National Park in 2001, this wilderness area was officially preserved as part of the Province of Quebec's natural heritage. The park includes the Vauréal Falls Area, which is considered to be a place of extraordinary natural beauty meriting public protection and government recognition. Anticosti is however so much more than the sum of its physical and natural features. It is impossible to fully grasp the ramifications of the park's newly acquired heritage status without taking into consideration the various social factors involved, as well as island's history of human inhabitation. When examined from this perspective, Anticosti becomes a model example of the inextricable relationship between humans and their environment, which are key elements essential to the process of protecting and promoting natural areas in the Province of Quebec.

Article disponible en français : Parc national d'Anticosti

The Natural Heritage of Anticosti Today

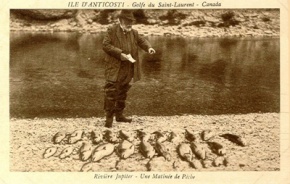

Located where the St Lawerence River joins the Gulf of St. Lawrence, Anticosti Island is 222 km (138 mi) long and 56 km (35 mi) wide at its maximum width, or roughly about the size of Corsica. It has 230 year-round residents, all of whom live in the village of Port-Menier. Many are descendants of the families that originally settled Anticosti. From May to December, the island is also home to seasonal workers, both loggers and foresters working in the forest and wildlife management areas, along with a number of outfitters. The island's economy is largely based on these outfitting operations, but forestry comes in as a close second. Tourist facilities can be found all along the coast on locations formerly inhabited by commercial fishermen, fish and wildlife rangers or lighthouse keepers.

Today a number of areas on the island are protected by the Government of Quebec because of their natural or geological features. Today there are two established biodiversity reserves on the island: Grand Lac Salé and Pointe-Heath .(NOTE 1) In addition, a national conservation park was established in 2001(NOTE 2), as a means of protecting Vauréal River Falls, the Observation River Canyon, and the Jupiter River watershed. These areas were selected as representative examples of the island's geological features, as well as for their spectacular scenic beauty.

In conjunction with these government policies, there are also more locally-based initiatives to protect and promote Anticosti's natural beauty and resources. The Industrial Research Chair has two interpretative sites open to visitors that are intended to illustrate the various forestry research projects in progress. Furthermore, all the outfitters organize tours of the island and talks on the state of conservation of various natural features of area, as well as of its flora and fauna. The municipal museum features the various types of fossils that can be found on Anticosti, as does the SÉPAQ outfitter at the Carleton site. Furthermore, Safari-Anticosti, a private outfitter, has created a sculpture garden that includes geological specimens. Finally, it should be noted that local residents requested that the Anticosti Park interpretation centre be set up in the main village, Port-Menier, so that the interpretive activities on the island's natural and geological characteristics would be more accessible to the general public.(NOTE 3) This request was however not included in the final proposal for creating Anticosti National Park.

The Natural Features of Anticosti Island

The western sector of Anticosti Island is forested predominately with coniferous species. The eastern end is covered with stands of spruce and peat bogs and a number of rare plants, including orchids, have been identified in the area. The topography of the island consists mostly of karst plateau with cliffs rising in the north. It is an enormous limestone mass stratified in multiple geological layers imprinted with numerous fossils. A large number of rivers have cut fjords and canyons into the topography of the island. The indigenous wildlife population (salmon, speckled trout, white-tailed eagle, seagull, fox, bear, etc.) was considerably altered through the deliberate introduction of mainland species over the course of the 20th century (white-tailed deer, moose, grouse, beaver, leopard frog, etc.), as well as by the effects of hunting and fishing. Human activity has considerably disrupted the island's ecosystems. For example, it lead to the disappearance of the black bear and to an overpopulation of white-tailed deer, Anticosti's emblem species . Without a natural predator, the latter has proliferated unchecked since it was introduced in 1905. At the last count, the population numbered 166,000 (NOTE 4) and overgrazing has prevented many plant species from growing back, which threatens even the very long-term survival of the white-tail itself. This realization, combined with the fact that the deer is a major attraction for outfitting activities, is currently motivating the development of conservation projects, as well as specialized scientific research funded by the Government of Quebec and the private sector.

The History of Anticosti Island

Anticosti Island was originally inhabited by Native peoples from both sides of the river, particularly the Micmac and the Innu.(NOTE 5) They would spend the spring season on the island hunting bear, the activity from which Natiscotec, the Innu name for the island, originated.(NOTE 6) In 1660, the island was granted to Louis Joliet by Louis the 14th of France, in recognition of his exploits in exploration. He settled there with his family and, on the western end of the island, he built a trading post, which was destroyed by the English in 1690. After that, it was mostly fishermen from the Isle of Jersey that settled on Anticosti. A number of dwellings and canneries (fish, lobster, etc.) were built along the coast of Anticosti Island, but no permanent village was established, although there were several attempts to do so. The majority of the settlers to particpate in these settlement projects were Acadians and French Canadians, many of whom would subsequently remain on the island.

Many imagine Anticosti to be a totally isolated and wild place.(NOTE 7) During the 19th century, Louis-Olivier Gamache helped perpetuate this idea. Between 1810 and 1854, all sorts of tales about the eccentric personality of this farmer and trapper fed the popular notion of the ‘Wild Anticosti', which eventually gave rise to the legend of the "Sorcer of Anticosti."(NOTE 8) The island had acquired a bad reputation amongst sailors as well, since numerous shipwrecks had occurred close to the island. As a result, in 1830, the Canadian government built a network of lighthouses on the island to be maintained by keepers and their families. A number of these lighthouses are still in operation although now mechanized.

The Island in the 20th Century

In spite of the wild image associated with the island, Anticosti was settled much earlier than the 20th century. One particular event has however frequently served to obscure the historical facts: that of the purchase of the island by Henri Menier in 1895. This event has frequently been identified as the starting point of most historical accounts on the region. The episode does nevertheless represent an important turning point for the economy and for the settlement of the island. And even more importantly, it affected the idea people had of the place, particularly the names given to places on the island.(NOTE 9)

Henri Menier, wealthy French industrialist dubbed the "king of chocolate", was also something of a Utopian.(NOTE 10) When he purchased Anticosti, his intention was to turn it into a hunting and fishing paradise for his personal use. With this in mind, he imported several species of game animals to the island and also had a hunting lodge built, which the locals would eventually refer to as the "chateau". The building was abandoned by the 1930s and deliberatly burned down in 1953.

Originally, Henri Menier had wanted to set up a self-sufficient economic model on the island. With the help of his steward, George Martin-Zédé, he had planned to establish settlements, infrastructures (railroads, aqueducts, electricity, health services, etc.), "modern" agriculture, and industrial development of the island's resources (forestry, hydroelectricity and fisheries). In pursuit of his goal, he did not hesitate to purchase or expropriate private holdings along the coast of Anticosti, thereby-to his manner of thinking-setting down the basis for a civilization in a hitherto unconquered wilderness:

And when we think back on what the island was like upon our arrival and all the work that has been done since... we will be certain that, because of the intensity of the effort and the sheer force of the human spirit spent to conquer the wilderness will have gone so far, that it will be then impossible to go back. No matter what happens in the future, Anticosti Island, justly referred to as the Queen of the Gulf, will no longer be able to revert to barbarism.(NOTE 11)

Menier died in 1914 having only partially accomplished his planned projects. In 1928, his heirs sold the estate to a Canadian paper-making company that later became Consolidated Bathurst, which continued with industrial-scale logging operations in addition to simultaenously developing another business venture: a hunting and fishing outfitters operation. The village (Port-Menier) remained company property, as did the wooded portion of the island. As a result, Anticosti residents would lose access to the island's forests until the mid 1980s.

The Government of Quebec acquired Anticosti in 1974 and continued to develop the same industries already established in the area.(NOTE 12) The province's ministry of tourism, wildlife and recreation managed the island and the village until 1982, when the local community of residents demanded and were granted municipal status.(NOTE 13) With the logging industry collapsing, tourist-related activities began to be developed, particularly by the Société des Établissements de Plein Air du Québec (SÉPAQ) [Quebec Society for Outdoor Recreational Services]. This government agency, is currently in charge of over half of the island's territory and offers tour packages for hunting, fishing and recreation. Since 2001, the agency has also taken on the management of Anticosti National Park.

Preserving and Promoting the Natural Legacy of Anticosti

Whereas certain conservation initiatives have concentrated on a single aspect of Anticosti's natural heritage - for instance, geology or the history of the Menier era - most cannot help but combine both natural and social aspects. For example, the Safari-Anticosti outfitting operation offers hunting and fishing packages, an exhibit featuring the Menier era and tours combining both historical and natural aspects of the area. SÉPAQ has opted for a similar approach to its outfitting and promotional activities associated with the national park, even though the latter has the sole mission of preserving the island's biodiversity.

Since the mid 19th century, scientists have been particularly interested in Anticosti from a geological point of view.(NOTE 14) This perspective is particularly evident in descriptions that refer to the island as a "fossil layer-cake." (NOTE15) Since the beginning of the 20th century, the island's plant life has also been the focus of many studies, including those of Jacques Rousseau and Brother Marie-Victorin.(NOTE16) Recent analyses have undertaken a more thorough assessment of Anticosti's ecosystem, particularly ecological changes brought about by the white-tailed deer, a species that has been the focus of both university and government research.(NOTE17)

These scientific studies, as well as the widespread exposure they have had in various circles, has awakened the public's interest in the island's natural heritage, thereby encouraging the conservation and tourist-oriented development of certain parts of the island.

Initiatives for conserving and promoting Anticosti's natural heritage are varied (NOTE18), but they do not all have the same degree of impact on a local level. Major repercussions have recently ensued from the creation of Anticosti National Park. The governmental recognition of the natural assets of a specific area of the island has given rise to discussions concerning the social and "cultural" changes that such recognition may bring, including how it will effect resident and local worker land use.

The Vauréal River and the falls are at the heart of Anticosti National Park. The heritage value of this site has however not always been recognized. For example, between 1850 and 1930, proposals brought foward to harness the river, in order to generate the electricity needed for commercial and forestry-related activities.(NOTE 19) It was only over the course of the 20th century that the island's industrial use gave way to a new vocation as a hunting and fishing paradise characterising romantic epitome of nature. The insular nature of Anticosti lends itself easily to this iconic representation of a virgin wilderness, untouched by man, in which one can rediscover the adventure and excitement of the early explorers. This image was quickly taken up by the island's outfitters, and at the end of the 20th century, concern for protecting Vauréal had emerged as an integral part of this romantic representation of nature. The splendour of the falls and the abundance of fish having become emblematic of Anticosti Island's natural wealth, it was then deemed necessary to protect them from the logging operations taking place on the island. Originally only intending to incorporate the area around the river and the falls, the plan for creating a park was founded on a romantic conceptualisation of the area and on the importance of preserving intact the rapidly disappearing tracts of virgin wilderness. One must however mention that, during the 20th century, considerable tracts of forest in the national park were logged and that, due to the presence of a large number of deer, the area's ecosystem was substantially altered, transforming what was once an area thickly forested with balsam fir into stands of spruce.(NOTE 20)

The Creation of a National Park on Anticosti: the Debates and their Consequences

The initiative for protecting Anticosti Island's natural heritage is composed of both nationall and regional-level environmental groups. This movement did not originate in the local community-as a matter of fact the choice of the park site was not met with unianimous approval, for both Anticosti residents and certain scientists were opposed to it. Some citizens suggested that the conservation area should include a number of historically significant sites in the Anticosti community. This proposal was rejected, but not without dividing the community in the process, mainly due to hunting and area access restrictions arising from the creation of the park. These governmental protection measures have imposed limits that are difficult for local residents to accept, due the fact that they have once again lost their cherished free acces to the island.

Thus, the process of officially recognizing Anticosti's natural heritage has been very divisive. On one hand, it has created tensions and conflicts concerning current and future land use, as the same piece of land has been long associated with very diverse uses. On the other hand, it has also failed to incorporate the various assets and locations deemed to have significant heritage value on both a local and national level. This has occurred in spite of all the official public rhetoric on a sustainable development that allows for the ongoing development of the social dimension of the project. The local population does not actively feel included in the new park project, even though the park zone has become part of the national heritage of the region without fully representing the concept that the population has of Anticosti. In spite of the natural beauty and symbolic importance of Anticosti Island, as it relates to the various dimensions of Quebec heritage, a global assessement of the situation is that the park continues to promote the image of the island as "nature without culture."

Geneviève Brisson, Ll.B. Ph.D.

Anthropologist

NOTES

Note 1: "Réserve écologique de Grand Lac Salé," Ministère du Développement durable, de l'Environnement et des Parcs, site consulted on October 31, 2007 [on line].

Note 2: "Réserve écologique de la Pointe-Heath," Ministère du Développement durable, de l'Environnement et des Parcs, site consulted on October 31, 2007 [on line].

Note 3: Municipalité de l'île-d'Anticosti, "Briefing presented to Guy Chevrette during public hearings concerning the planned Vauréal River park," 1999.

Note 4: F. Potvin, P. Beaupré and C. Dussault. La population de cerfs de l'île d'Anticosti: élaboration de modèles densité-habitat et prévisions pour l'horizon 2000- 2100, NSERC-Anticosti Forest Products Industrial Research Chair, Université Laval, 2006, 45 p.

Note 5: For a historic persective on the island see P. Frenette (ed.), Histoire de la Côte-Nord (Québec City: Les éditions de l'IQRC, 1996); D. Mc Kay, Le paradis retrouvé, Anticosti (Montréal: La Presse, 1979) and L.-E. Hamelin, "Mythes d'Anticosti," in Recherches sociographiques, 23: 1-2 (1982), pp. 139-162.

Note 6: Commission de toponymie du Québec, Noms et lieux du Québec, Québec City, the official editor, 1996.

Note 7: G. Brisson, "La capture du sauvage. Les transformations de la forêt dans l'imaginaire québécois, le cas d'Anticosti (1534-2001)," Thèse de doctorat (anthropologie), Université Laval, 2004, 475 p.

Note 8: R. Choquette, Le sorcier de l'île d'Anticosti (Montréal: Fides, 1976).

Note 9: W. P. Anderson, Place-names on Anticosti Island, Québec (Ottawa: F. A. Acland, 1922).

Note 10: G. Messence and B. Logre, Chocolat Menier, évitez les contrefaçons! (Paris: Éditions du May, 2005), 191 p.

Note 11: J. Schmitt, Monographie de l'Ile d'Anticosti (Golfe Saint-Laurent), (Paris: Plon-Nourrit, 1904), p. 347. [Original citation translated into English]

Note 12: G. Brisson, "L'État et la forêt: une appropriation de l'espace sauvage à l'île d'Anticosti" in Frédéric Lasserre and Aline Lechaume (eds.), Les territoires pensés - représentations territoriales au Québec (Québec: PUQ, 2003), pp. 179-192.

Note 13: P. Ayotte and G. Galipeau, Aspirations de la population de l'île d'Anticosti (Québec: Ministère des Affaires municipales, 1974).

Note 14: Works by James Richardson (1856), Hyatt, Verukk and Shaler (1861), Laflamme (1900) and Scuchert and Twenhofel (1908 and 1928) have helped highlight this aspect. Also see Frenette, op. cit., p. 413.

Note 15: The expression [Original citation translated into English] can be found in, among others, Y. Ouellet and A. Dumas, Anticosti, l'Éden apprivoisé (Québec: Trécarré, 2000).

Note 16: J. Rousseau, Notes sur l'ethnobotanique d'Anticosti (Montréal: Montréal Botanical Garden, 1948); Marie-Victorin (Conrad Kirouac) and Rolland Germain, Flore de l'Anticosti-Minganie (Montréal: PUM, 1969), 523 p.

Note 17: The Anticosti Industrial Chair oversees these projects, carried out for the most part by Laval University's Faculty of Forestry and Department of Biology and by government researchers from Québec's Ministère des Ressources Naturelles et de la Faune [Ministry of Wildlife and Natural Resources].

Note 18: G. Brisson, "Consulter le public et intégrer le paysage vécu: le rendez-vous manqué du Parc de conservation d'Anticosti," Études Canadiennes/Canadian Studies, No. 62, 2007, 17 p.

Note 19: Schmitt, op. cit.; P. Combes, Exploration de l'île d'Anticosti: rapport de M. Paul Combes (Paris: J. André, 1896).

Note 20: Société de la Faune et des Parcs du Québec, Plan directeur, Parc national d'Anticosti [Anticosti National Park Management Plan], Québec, Dirction de la Planificaiton des Parcs, Société de la Faune et des Parcs du Québec, 2004, 52 p.

Bibliography

Brisson, G., « La capture du sauvage. Les transformations de la forêt dans l'imaginaire québécois, le cas d'Anticosti (1534-2001) », thèse de doctorat (anthropologie), Université Laval, 2004, 475 p.

Dumais, N., L'embarquement pour Anticosti, Montréal, P. Tisseyre, éditeur, 1976.

Gagnon, L. et J. Schell, Anticosti, guide écotouristique, L'Acadie, Broquet, 1994.

Guay, L., À la découverte des îles du Saint-Laurent, de Cataracoui à Anticosti, Québec, Septentrion, 2003.

Lejeune, L., L'époque des Menier à Anticosti, St-Hyacinthe, Éditions JML, 1989.

Lejeune, L. et J.-N. Dion, Anticosti, l'époque de la Consol, St-Hyacinthe, Éditions JML, 1989.

McCormick, C., Anticosti, St-Nazaire-de-Chicoutimi, Éditions JCL, 1979.

MacKay, D., Le paradis retrouvé; Anticosti, Montréal, La Presse, 1983.

Marie-Victorin (Conrad Kirouac), Croquis Laurentiens, Montréal, Fides, 1969 [1924].

Martin, P.-L., La chasse au Québec, Montréal, Boréal, 1989.

Nash, R., Wilderness and the American Mind. New Haven, Yale University Press, 1982.

Roper, E., Ice Bound or The Anticosti CrusoesMM, Londres, Partridge & Co, non daté.

The Governor and Company of Anticosti, The Settler and Sportman in Anticosti. Londres, Moms & Co., 1885.

Additional DocumentsSome documents require an additional plugin to be consulted

Images

-

Journal de l'Île d'An

Journal de l'Île d'An

ticosti de Geor... -

Pavillon de pourvoiri

Pavillon de pourvoiri

e aux abords de... -

Port-Menier, vue aéri

Port-Menier, vue aéri

enne -

Port-Menier. La villa

Port-Menier. La villa

.

Vidéo

Documents PDF

-

Anticosti : un parc excessif

Anticosti : un parc excessif

-

Anticosti (poème)

Anticosti (poème)

-

Le croque-mitaine du Golf Saint-Laurent

Le croque-mitaine du Golf Saint-Laurent

-

Oui j'ai aimé... Ou la vie d'une femme

Oui j'ai aimé... Ou la vie d'une femme