Fort de Chartres in Illinois

par Gagné, Joseph

Located near Prairie du Rocher in the state of Illinois, Fort de Chartres is the only stone fort constructed by the French in the heart of the North American continent. Three forts were consecutively built between 1720 and 1755, bearing witness to the French colonial empire established in the Mississippi basin during the XVIIIth century. Abandoned for many decades, it was during the wave of historical site development in the first half of the XXth century that the state of Illinois partially rebuilt it to perpetuate the memory of the French presence in the region.

Article disponible en français : Fort de Chartres en Illinois

A Relic of a Colonial Empire

Fort de Chartres as it appears today consists of the reconstructed north wall along with its two bastions. Besides the original powder magazine, the guardhouse, as well as the storehouse, have been reconstructed. The latter contains a museum exhibiting archaeological artefacts discovered on the grounds. The buildings that have not been reconstructed are commemorated by wooden frameworks evoking their original forms. The symbolic importance of Fort de Chartres resides in the fact that it represented the administrative and economic headquarters of the Illinois Country, also known as Upper-Louisiana, during the French colonial period.

An Expression of Territorial Possession and Control

Fort de Chartres was the most imposing French military construction between Niagara and Mobile (NOTE 1). It was named in honour of Louis, Duke of Chartres, son of the regent Philippe d’Orléans. It quickly became the main trading post and supply center for the Illinois country. Its main function, however, was to express formal French domination in a territory which, despite colonisation, remained largely composed of wilderness. Thus, it supplied a military presence to the region with the goal of pacifying the Fox and Chickasaws Nations, who were enemies to the French. Not only did the commander of the fort have the responsibility of controlling these two Nations, but he also had to constantly negotiate with allied natives to prevent them from changing alliance through closer ties with the English. This military and political presence thus reaffirmed the possession of the territory, increasing resistance against westward English colonization.

The First Fort

The French West India Company undertook the construction of the first Fort de Chartres between 1719 and 1721. Its erection was meant to pursue three economic goals set by the company: to facilitate the fur trade, to kick-start lead mining, and to develop regional agriculture. The company decided to build the new fort between two villages, should they ever need to quickly intervene in either place: Cahokia to the north, and Kaskaskia to the south. Its construction, led by Captain Pierre Dugué, sieur de Boisbriant and first lieutenant of the king, was fairly rudimentary. Its shape was rectangular with two diagonally opposed bastions. Its wooden palisade, measuring about 58 metres on each side, was surrounded by a dry moat. This fort contained only three buildings, lodging up to about one hundred men. Two chapels, one in Prairie du Rocher, and the other in Saint-Philippe, were managed by the parish of Saint-Anne which, in turn, was alternately run by the Society of Foreign Missions, Jesuit, and Recollect missionaries. Unfortunately, the fort, constructed at a “musket’s shot” distance from the Mississippi river, was regularly flooded by rising waters in the spring. Consequently, the first fort was only used for a few years before being replaced.

The Second Fort

The second fort was constructed sometime around 1725. Erected in proximity to the first fort, it was a little smaller than its predecessor but it included four bastions. A small chapel and a hospital were constructed outside the palisade. Just like the first fort, it often flooded. After the West India Company’s failure to find gold and precious minerals, the government of New Orleans took control of the region and the fort. The decrepit state of the fort forced the garrison to move to Kaskaskia in 1747.

The Third Fort

Though the land exploitation never yielded precious metal deposits, the region turned out to be an important source of lead and especially of fertile ground that was favourable to agriculture. The Illinois country quickly became a sort of “breadbasket to Louisiana”(NOTE 2). In order to protect commerce and exchanges, the colonial administration decided from then on that a stronger military presence was required in the area.

Initially, the government of New Orleans wanted to reconstruct Fort de Chartres in Kaskaskia. Founded in 1703, this community was indeed larger than that of the old fort. In 1751, governor Vaudreuil(NOTE 3) decided, however, to leave the administrative center of the Illinois where it then stood. To avoid annual floods, however, it was reconstructed about one kilometre north of the first fort, under the supervision of engineer Jean-Baptiste Saucier. Construction was difficult. The lack of experienced workers and the many desertions slowed the work effort. Furthermore, construction material was brought in from north of Prairie du Rocher, located several kilometres from the construction site. The cost of construction, evaluated at some five million livres, according to some estimates, rapidly escalated to the point where the French crown threatened to abandon the work in progress. The new governor of New Orleans, Louis Billouard de Kerlerec, assured the French minister that construction was nearly complete. In reality, the fort would only be completed in 1760.

Contrary to Louisbourg or Michilimackinac, the inhabitants did not live within Fort de Chartres. Instead, the Louisiana government founded a village that shared the same name outside of the enclosure. In 1752, Commander Jean-Jacques Macarty’s census tallied the population to 198 French, 89 black slaves and 36 panis (native) slaves. Thus, the population of the village of Chartres was classed third in importance after Cahokia and Kaskaskia. The fort itself could accommodate up to 300 soldiers.

This new fort, as would be revealed by archaeological digs, measured up to 52 metres from one bastion tip to another. According to contemporary eyewitnesses, the walls were covered by plaster, it measured between 18 and 24 inches in thickness, and it had gun loops at regular intervals. Each bastion wall contained two post-holes for cannons. All agreed that the gate was impressive and of “nice appearance”(NOTE 4). Inside the enclosure were the commander’s house and that of the commissary, the storehouse, the guardhouse and two soldier’s barracks. At the heart of each bastion were the powder magazine, a bake house, and a prison comprised of four dungeons that were divided between the underground and the second floor. Philip Pittman wrote, in 1764: “It is generally allowed that this is the most commodious and best built fort in North America”(NOTE 5).

The End of the Fort

Although it was constructed out of stone, the new fort was not made to resist grand artillery fire; rather, it was made to resist native sieges. Luckily, despite the apprehensions of Commander Pierre-Joseph Neyon de Villiers, Fort de Chartres was never the target of any English offensive. In theory, should Canada be lost, the head staff of the French army expected to retreat to it with a few thousand soldiers in order to attack Virginia and Carolina (NOTE 6). In the end, this plan was never put into action (NOTE 7).

After the signature of the Treaty of Paris in 1763, officialising the French defeat at the end of the Seven Years’ War, Fort de Chartres wound up in British hands and was renamed Fort Cavendish (NOTE 8). The new occupants of the fort quickly faced the same problems as did their predecessors: disease, in particular malaria, and soil erosion. The British tried different methods to attenuate the effects of the erosion that threatened to engulf the fort, but maintenance costs soon exceded the fort’s worth in the eyes of British authorities. The garrison thus abandoned it in 1771. One year later, the South wall and its bastions collapsed.

As for the residents of the East shore of the Mississippi, most moved onto the western shore, which was thought to be more hospitable because of the presence of a Spanish catholic government (NOTE 9). The village of Chartres disappeared shortly after 1765 making way instead for the parish of Saint-Joseph in Prairie du Rocher, which still exists to this day.

From Deterioration to Valorization

Once abandoned, Fort de Chartres was only occasionally occupied by errant natives. The fort quickly deteriorated and vegetation reclaimed the land; thus, by 1804, about thirty years after having been abandoned, the presence of trees measuring 7 to 12 inches in diameter was reported within the old enclosure (NOTE 10). The repetitive scavenging of material from the fort by the inhabitants of neighbouring communities contributed to the gradual disappearance of its last remains.

In 1913, the state of Illinois purchased the nearly 20 acres of land on which the ruins lay, probably giving in to the insistence of certain history amateurs and professionals, like Joseph Wallace who, in his 1904 article, strongly suggested the preservation of this “relic” (NOTE 11). Henceforth established as a state park, work began in 1917 to restore the powder magazine, the only relatively intact structure in the fort and thought to be the oldest military structure in Illinois.

The partial reconstruction of the fort, undertaken through a governmental construction program, spread over many years: the storehouse was rebuilt in 1929; the gate in 1936; the guardhouse in 1940; finally, the foundations of anything that wasn’t reconstructed were covered with a layer of cement to stop erosion. In 1966, the site was recognized as a National Historic Landmark before being added to the National Register of Historic Places in 1974.

Systematic archaeological digs at Fort de Chartres were only undertaken in the 1970’s and 1980’s. These first systematic digs were held following public pressure insisting that the fort be rebuilt in the most authentic way possible (NOTE 12): thus, the North wall was reconstructed during the 1980’s on its original foundations. Essentially carried out on the site of the third fort, these digs were followed by a second archaeological search which confirmed the location of the first Fort de Chartres.

A Place Enriched By French Military Memory in the United-States

The efforts invested in research and reconstruction guarantee Fort de Chartres’ place in the heart of the Illinois Country’s French heritage. Currently managed by the Illinois Historic Preservation Society, the site is open to visitors who not only have access to its museum, but also to a library dedicated to the history of the fort. The area often hosts various historical interpretive events geared towards the general public, as well as re-enacting gatherings. The fort also hosts many yearly festivals, such as the “Bal du Commandant”. Community affection for this heritage site is expressed notably through private donations which supplementState funding. Public support, whether it be expressed through monetary donations or volunteer work, is assured notably by the Coureur des Bois gun club, and it should secure the fort’s maintenance and promotion for years to come.

Joseph Gagné

Post-graduate student, Université Laval

Additional DocumentsSome documents require an additional plugin to be consulted

Images

-

L'interprétation hi

L'interprétation hi

storique au for... -

«Fort Chartres on the

«Fort Chartres on the

Mississippi Ri... -

À gauche, la Maison d

À gauche, la Maison d

es gardes, reco... -

Amérindien Kaskakia

Amérindien Kaskakia

-

Bienvenue au fort de

Bienvenue au fort de

Chartres -

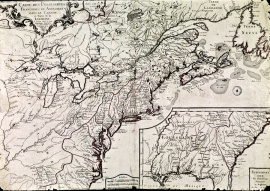

Carte des Possessions

Carte des Possessions

françoises et... -

Carte moderne montran

Carte moderne montran

t la localisati... -

Carte où l'on aperçoi

Carte où l'on aperçoi

t le fort de Ch...

-

Chambre de soldats au

Chambre de soldats au

fort de Chartr... -

Des figurants commémo

Des figurants commémo

rent la prise d... -

Des figurants incarne

Des figurants incarne

nt les troupes ... -

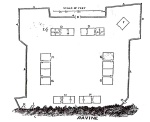

Dessin du fort de Cha

Dessin du fort de Cha

rtres tel qu'il...

-

Dessin du fort de Cha

Dessin du fort de Cha

rtres tiré de l... -

Entrée du fort de Cha

Entrée du fort de Cha

rtres. Notons q... -

Fort de Chartres tel

Fort de Chartres tel

que relevé par ... -

Fort de Chartres: les

Fort de Chartres: les

meutrières et ...

-

Foyer dans la chambre

Foyer dans la chambre

d'officier du ... -

L'intérieur de la cha

L'intérieur de la cha

pelle de la mai... -

L'intérieur de la cha

L'intérieur de la cha

pelle de la mai... -

L'intérieur de la voû

L'intérieur de la voû

te de la poudri...

-

La plupart des bâtim

La plupart des bâtim

ents du fort de... -

La porte du fort de C

La porte du fort de C

hartres -

La poudrière du fort

La poudrière du fort

de Chartres ava... -

La poudrière du fort

La poudrière du fort

de Chartres. Bi...

-

Le fort de Chartres t

Le fort de Chartres t

el qu'on le ret... -

Le fournil du fort de

Le fournil du fort de

Chartres: à l'... -

Plaque commémorative

Plaque commémorative

du fort de Char... -

Plaque commémorative

Plaque commémorative

du fort de Char...

-

Portail du fort de Ch

Portail du fort de Ch

artres après la... -

Porte du fort de Char

Porte du fort de Char

tres avant les ... -

Vue aérienne du fort

Vue aérienne du fort

de Chartres de ...

Document PDF

Hyperliens

- Fort de Chartres - official website

- Center for French Colonial Studies

- Visitors’ Guide to French Colonial Country [en anglais]

Catégories

Notes

1. René Chartrand, The Forts of New France: The Great Lakes, the Plains and the Gulf Coast, 1600-1763, Oxford, Osprey Publishing, 2010, p. 43.

2. For example, in 1748, 800 000 livres of flower were sent to New Orleans. Carl J. Ekberg, French Roots in the Illinois Country: The Mississippi Frontier in Colonial Times, Urbana et Chicago, University of Illinois Press, 1998, p. 220.

3. Pierre de Rigaud de Vaudreuil de Cavagnial was the governor of Louisiana between 1742 and 1753. He is the same Vaudreuil who would be the governor general of New France during the Seven Years’ War.

4. Philip Pittman, quoted in Chartrand, The Forts of New France: The Great Lakes..., pp. 43-44, and John Jennings, Journal from Fort Pitt to Fort Chartres in the Illinois Country, The Pennsylvania Magazine of History and Biography, Vol. 31, No. 2 (1907), p. 155.

6. Louis-Antoine de Bougainville, Écrits sur le Canada. Mémoires – Journal – Lettres, Québec, Septentrion, 2003, p. 33.

7. When the Eastern shore of the Mississippi was transferred to the English following the signature of the Treaty of Paris in 1763, the commander of the fort (Neyon) was forced to wait either for the arrival of the English or that of his successor. He eventually lost patience and left the fort in June 1764, a few months before the arrival of his replacement Louis Saint-Ange de Bellerive. It is he who handed the fort over to the British on 10 October 1765. With his total of about thirty men, he re-joined the newly founded post of Saint-Louis.

8. Library and Archives Canada, Nouvelle-France: Correspondance officielle, 1re série, A1, 1re série, vol. 17, Fº220-228, Procès-verbal de la cession du fort de Chartres, le 10 octobre 1765.

9. In reality, the massive Anglo-American influx that the French feared was belated until the end of the century. Ekberg, French Roots…, pp. 91 and 241.

10. Amos Stoddard, quoted in Joseph Wallace, “Fort de Chartres–Its Origin, Growth and Decline”, in Transactions of the Illinois State Historical Society For the Year 1903, Springfield, Phillips Bros., 1904, p. 113.

11. “Something, however, may yet be done to safeguard the memory of this ancient citadel. The State of Illinois can, and I think it should, purchase the site of the fort, clear and enclose the ground, trace out as far as possible the lines of the exterior walls and the foundations of the principal buildings, and transform it into a historic little park. And thus this relic and legacy to us from the remote past might be, in some material form, handed down to posterity.” Wallace, Fort de Chartres…, pp. 116-117.

12. A new roof was added to the powder magazine in 1974, but it doesn’t follow historical rigour, giving it a double- sided slanted roof instead of respecting the original vaulted shape.

Bibliographie

Bougainville, Louis-Antoine de, Écrits sur le Canada. Mémoires – Journal – Lettres. Québec, Septentrion, 2003, 425 p.

Brown, Margaret Kimball et Lawrie Cena Dean, The Village of Chartres in Colonial Illinois 1720-1765, Nouvelle-Orléans, Polyanthos, 1977, 1042 p.

Chartrand, René, The Forts of New France: The Great Lakes, the Plains and the Gulf Coast, 1600-1763, Oxford, Osprey Publishing, 2010, 64 p.

Ekberg, Carl J, French Roots in the Illinois Country: The Mississippi Frontier in Colonial Times, Urbana et Chicago, University of Illinois Press, 1998, 359 p.

Jelks, Edward B. et Carle J. Ekberg, Excavations at the Laurens Site. Probable Location of Fort de Chartres I, Springfield, Illinois Historic Preservation Agency, 1989, 136 p. Coll. « Studies in Illinois Archæology (No.5) »

Jennings, John, Journal from Fort Pitt to Fort Chartres in the Illinois Country. The Pennsylvania Magazine of History and Biography, Vol. 31, No. 2 (1907), pp. 145-156. [En ligne : http://www.jstor.org/stable/20085378].

Keene, David, « Fort de Chartres: Archaeology in the Illinois Country », dans John A. Walthall, dir. French Colonial Archaeology: The Illinois Country and the Western Great Lakes, Chicago, University of Illinois Press, 1991, p. 29-41.

Price, Anna, « French Outpost on the Mississippi: The Three Lives of Fort de Chartres », Historic Illinois Magazine (1er juin 1980). [ En ligne : http://www.ftdechartres.com/articles/article/6007979/101616.htm ].

Wallace, Joseph, « Fort de Chartres–Its Origin, Growth and Decline », dans Transactions of the Illinois State Historical Society For the Year 1903,Springfield, Phillips Bros., 1904, p. 105-117.