Saving the American White Pine

par Quenneville, Raymond and Thériault, Michel

The white pine, often described as a majestic tree of extraordinary size, has fascinated and inspired naturalists and artists for generations. With a height of more than 40 m and a trunk diameter often more than 100 cm, it is the giant of northeastern North American forests. In the right conditions, the white pine is fast-growing and surprisingly long-lived. Some trees alive now witnessed the arrival of European explorers of the early seventeenth century. Of the millions of hectares of pine forests that covered eastern North America 400 years ago, only a few remain, between 0.25 and 5% according to various authors. These scattered forests, changed and weakened, depend today on the care that owners and governments are willing to provide. What is being done to ensure the survival of this precious natural heritage?

Article disponible en français : Pin blanc d'Amérique: préservation

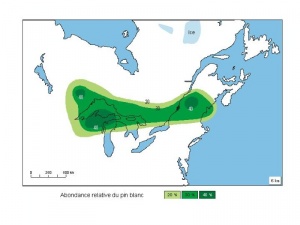

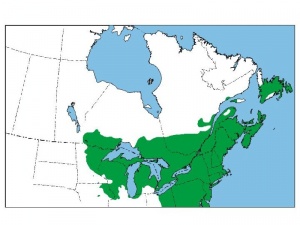

The white pine (Pinus strobus L.) that we know today appeared on the North American continent some tens of millions of years ago. The species evolved with the climate and geological phases, which isolated it and led to its differentiation from other pine species found in Canada and the United States. This pine, which died out in Europe, is now found only in the northeastern part of the North American continent. During the last glaciation the species gradually died out in the northern territories, to occupy only a limited area in the foothills of the Appalachians in the southern United States. With the gradual melting of the glacier about ten thousand years ago, the white pine spread north again, reaching its greatest numbers about 6000 years ago. At that time, the greatest concentrations of pines were found along the valleys of the Saint Lawrence and of the Great Lakes. It made up between 30% and 40% of the forests of that great area.

In North America the white pine has always been part of people’s lives. Native people used its bark for the outer covering of long houses, and its resin mixed with ash served as a sealant, which was used in making bark canoes and other objects (Josephy, 1992).

The white pine is one of the best lumbers produced in temperate climates. Its fine grain and high-quality fibre make it suitable for many uses: construction, furniture, boats, etc. For this reason it played a very important role in the economic life of French America between the arrival of the first European colonists and the end of the nineteenth century. Especially in the nineteenth century, logging and the log drive of this valuable resource contributed to economic growth and provided a living for generations of workers. At that time, billions of cubic metres of white pine were taken from the forests.

As could be

expected, this overexploitation had considerable ecological consequences. John

A. Macdonald, prime minister of Canada, showed foresight when he wrote in 1871:

“We are recklessly destroying the timber of Canada and there is scarcely a

possibility of replacing it.” (Letter to Sandfield Macdonald, June 1871)

He was right, for today North American white pine populations are in a critical

state. Over the last centuries, pine stands have been drastically eliminated or

so changed by logging that their survival is threatened. Clifford Ahlgren

summarized the situation in 1976:

Modern influences on succession, even in remote areas, tend to eliminate rather than perpetuate the longer lived red pine and white pine following natural disturbances. These species cannot be restored by natural means to the position they represented in the forests of the past. [...] A choice must be made between (1) establishing, through man's efforts, forests resembling the primeval stand or (2) by natural means, permitting the development of a forest in which other species predominate. (Journal of Forestry, March 1976)

The main causes of the gradual disappearance of the white pine are:

1) overlogging

2) changes due to fire regimes

3) the appearance of an exotic disease, the white pine blister rust (Cronartium ribicola J.C. Fisher)

4) competition from other forest species, in particular the balsam fir.

To understand these better, we must know the ecological context in which the white pine lives.

Ecology of the white pine

The white pine is present from Newfoundland to the extreme southeast of Manitoba, including the southern parts of Quebec and Ontario. It is found around the Great Lake region as well as the Maritime provinces, and in the Appalachians of the United States as far as northern Georgia.

This is a species that can adapt to a great diversity of substrata. However, growth of the white pine is often favoured by sandy, well-drained soils (Kafka and Quenneville, 2006).

The white pine provides food and shelter to many animal species. Its seeds are attractive to a great variety of birds and small mammals, and its foliage is grazed by the American hare and the Virginia deer. Veteran trees, living or dead, provide refuge to eagles, magpies and a number of mammals. The black bear often digs its den under the roots of a large pine. Its cubs will later take refuge in the branches of the tree (Rogers et Lindquist, 1992).

A species adapted to fire

The ecology of the white pine is in most cases closely related to forest fires (Van Wagner, 1965). The species is adapted to fire, and its resistance to forest fires increases with age. The thick bark of adult trees protects the trunk from heat, and the distance of the first branches from the ground does the same for the foliage. Periodic low-intensity fires have helped to maintain the species for thousands of years. The occurrence of a fire in a pine stand favours preparation of an adequate germination bed by eliminating the top level of forest floor and the aerated part of humus. It reduces competition from other species more susceptible to fire and creates openings in the forest cover, allowing light to reach the ground. All these conditions help seedlings to grow for a time. If there is no fire, the white pine cannot easily become established in places where its competitors are abundant. This is clearly the case in the provinces of Ontario and Quebec, and in some of the northern states of the United States. Numerous studies have pointed out the inability of pine stands to regenerate in the absence of fire. This phenomenon is of great concern to the scientific community, which is trying to protect the few stands of pines that have escaped logging.

The concordance between distribution of the white pine and territory occupied by First Nations peoples suggests a link between human use of fire and the development of the great white pine forests. Burning was widely used to the native people of North America for agriculture and hunting, and for development of their land (William, 2003). Could this practice have helped in many places to create conditions favourable to the spread of white pines? It is quite possible that it did.

In some parts of Nova Scotia and New Brunswick as well as some other places in its distribution area, one sees a good density of white pine seedlings where the fire did not occur. It seems that other disturbances such as insect infestations and windthrow (trees blown down by wind) can also create conditions favourable to regeneration of white pine. The absence of competing species also allows the pine to maintain itself on poor and dry soils (slopes, rocky outcrops, fallen rocks, zones of anthropogenic disturbances, etc.).

The main pathogens

The main disease affecting pine forests is white pine blister rust. In a number of places the trees are seriously affected by this exotic fungus, which was not present in ancient ecosystems (Wilkins, 1994). Although it causes most harm to regeneration, it can also affect trees of any age. The disease cycle passes through an intermediary host, Ribes (currants and gooseberries). The infected leaves produce spores which, dispersed by wind, transmit blister rust. The fungus attacks the needles first, and then spreads to the branches and trunk, killing the tree.

Another aggressive pathogen is the white pine weevil (Pissodes strobi Peck), an indigenous insect whose influence was surely less marked at the time when there were more forest fires. This insect feeds on the terminal leaders of young stems, which become deformed, and growth of the tree is slowed down.

Side effects of logging

Logging has greatly changed the structure of pine stands, and has encouraged the implantation of new species that compete with the pine for water, light and nutrients. These new populations, where maple and fir are kings and the pine is a minority, no longer have the structure necessary for the development of pine stands.

Selection due to logging has also affected the genetic diversity of the species. Since almost all the finest specimens were harvested in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, perpetuation of the species depends in many places on trees that are less vigorous, unhealthy, or suffering from various deficiencies.

Conservation efforts

A number of small areas have been reserved over the last thirty to fifty years in the distribution area of the white pine, in order to preserve mature forests. These total preservation areas promote protection of adult trees, but current management practices only rarely allow for solutions to the problems of regeneration and for ensuring the growth of new trees.

Some Canadian and American national parks have adopted fire as a tool for managing ecosystems. They carry out controlled burns under prescribed conditions to recreate the effects of natural processes, and to allow pine forests to survive or develop. In Canada, the work of the Petawawa Research Forest, as well as work by the province of Ontario, have opened the way to use of this tool (McRae et al., 1993). The La Mauricie National Park has applied these techniques, and since 1995 has carried out about fifteen burns for this purpose. The results so far have been very encouraging (Quenneville and Thériault, 2001). A low-intensity surface fire in spring conditions allows a new generation of white pine to germinate and grow, without endangering mature trees. Other national parks in Ontario, Quebec and the Atlantic Provinces that faced similar challenges have used or will soon use controlled burning to regenerate white pine and other species that depend on fire.

In other places, efforts at reforesting to rebuild forest reserves have been carried out since the 1970s. The results were mixed at first. Some plantings in open areas were attacked by the white pine weevil and by white pine blister rust. New approaches have been developed, sometimes favouring mixed plantings (for example, in combination with red pine and Norway spruce), and underplanting. In all these cases, careful monitoring and regular maintenance of the plantings are required, to ensure that the new growth gets the right amount of light for seedlings to grow and to avoid conditions favourable to the spread of blister rust. In the United States, shelterwood cutting has been widely used. This system consists of removing some of the mature trees to allow penetration of light, and of various mechanical or chemical treatments designed to prepare the soil or to control competing plant species.

While a number of research groups are working to develop white pines genetically resistant to rust, others prefer the direct approach: they systematically prune plantings to eliminate affected branches and prevent the spread of the disease. Some go so far as to eradicate currants and gooseberries (Ribes spp.) near plantings, since plants of this kind favour development of the fungus responsible for the disease.

New commercial management systems

Forestry companies have used a succession of techniques to reduce the negative impact of their actions and to obtain maximum yield. The first approaches emphasized protection of growing trees in view of the harvest, rather than ensuring that the resource would be renewed. In the last few years, forestry approaches pay more attention to choosing sites and preparing the terrain to promote germination and growth of seedlings. The governments of Quebec, Ontario and several American states, in collaboration with research groups and universities, are trying out practices that promote both production of high-quality wood and the long-term sustainability of white pine populations (Partenariat innovation forêt, 2008). The scientists of the Institut québécois d'aménagement de la forêt feuillue are working to develop new forestry models and approaches that take account of the ecological processes favourable to the white pine.

The disappearance of the American white pine forests is a prime example of the sometimes irreversible consequences that human negligence can have for the environment. This abundant resource, which seemed almost inexhaustible, was in fact vulnerable. In only few centuries this species, well-established for thousands of years, was put in peril. This situation shows clearly that our relation to our natural heritage is crucial. The efforts that are being made today to preserve the remaining pine stands and to maintain this unique ecosystem in the long term are of vital importance.

Raymond Quenneville

Fire Management Specialist

Parks Canada

Quebec Service Centre

Michel Thériault

Fire Management Specialist

Parks Canada

La Mauricie National Park

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Ahlgren, Clifford E., « Regeneration of red pine and white pine following wildfire and logging in North eastern Minnesota », American Journal of Forestry, Vol.74 no. 3, 1976, 6 p.

Beaulieu, Jean, La noble histoire du pin blanc, Recueil des conférences du colloque tenu à Mont-Laurier les 3 et 4 juin 1998, 1998, pp. 5-12.

Josephy, Alvin M. Jr., America in 1492 - The World of the Indian poeples Before the Arrival of Colombus, Alfred A. Knopf, New York, 1992, 477 p.

Kafka, Victor et Raymond Quenneville, Cadre pour la restauration écologique du pin blanc et du chêne rouge, Parc national du Canada Forillon, Service de la conservation des écosystèmes, Parcs Canada, 2006, 67 p.

McRae, Douglas J., J. Timothy Lynham and Robert J. French, Implementing a successful understory red pine and white pine prescribed burn, Proceedings paper from the white pine/red pine workshop, Chalk River, 1993, 11 p.

Partenariat innovation forêt, Les grands pins au Québec : Un choix d'avenir, Bibliothèque et Archives nationales du Québec, ISBN : 978-2-9808476-1-5, 2008, 28 p.

Quenneville Raymond et Michel Thériault, « La restauration des écosystèmes de pin blanc (Pinus strobus) : Un enjeu majeur pour le parc national de la Mauricie », Le Naturaliste canadien, vol.125, no. 2, 2001, pp. 39-42.

Rogers, Lynn Leroy and E.L. Lindquist, Supercanopy white pine and wildlife, The white pine symposium, Duluth, M.N., 1992, pp. 39-43.

Van Wagner, Charles E., Prescribed burning experiments red and white pine, Department of Forestry Canada, Publication no. 1020, Forest Research Branch, 1965, 27 p.

Wilkins, Charles, « The mythic white pine is in trouble », Canadian Geographic, September/October, 1994, pp. 59-66.

Williams, Gerald W., References on the American Indian use of fire in ecosystems, USDA Forest Service, Washington, D.C., 2003, 94 p.