Harvesting the Stands of Eastern White Pine

par Quenneville, Raymond

In recent centuries, the forests of eastern North America have undergone drastic changes. Land clearing by European settlers and the various episodes of logging that followed have irrevesably altered the ecological course of timber stands across the continent. The white pine forests were not spared this upheaval, for they were the target of relentless harvesting that lasted over 250 years-a process so intense that the majority of the stands once populated by this precious resource have now disappeared. The logging reached its peak in the 19th century, initially in order to meet the needs of the British Navy and then to support the development of Canadian and American cities, towns and villages.

Article disponible en français : Pin blanc d'Amérique: exploitation des peuplements

The Great White Pine Forests

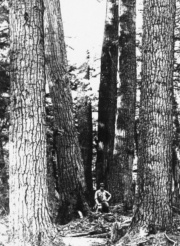

The first explorers to reach the coasts of the new continent were confronted with an untamed wilderness and forests that had been managed for millennia according to the laws governing nature and the subsistence economy practiced by the Native American peoples. These landscapes were described by a number of authors, each praising the magnificence and quality of the woodlands. The explorers' accounts highlight the abundance and omnipresence of the white pine (Pinus strobus L.), a tree of truly gigantic dimensions.

Testimonies such as the following are common in historical accounts: "As far as the eye can see, the country offered a regular succession of mountains gradually rising in height... the peaks and valleys are thickly wooded, especially with white pine, birch, spruce, and balsam, as well as a few small cedar trees." (Ingall, 1829 - original citation translated into English)

The white pines found on the continent were very large indeed: "During the period that I am describing, they felled only the biggest trees; there were many pines with a diameter of four to five feet at the bottom of the trunk." (Boucher, 1952 - original citation translated into English)

A Heritage Resource

For many millenia, these impressive trees were intimately linked to the lives of the various peoples of North America. It is said that the Iroquoians of the St. Lawrence Valley lived in the land of the white pine. The tree was at the centre of their concept of the cosmos, and they called it "the tree of peace." Later on, it truly became manna in the desert for the first European settlers, particularly because the tree has so many uses. For many years, the white pine was eastern Canada's most highly valued conifer and, at a certain point, was even considered as the most important source of lumber in the world. The first reason the tree is desirable is because it is the largest tree of eastern forests and due to the high branches, it has a very long, knot-free trunk. Although the wood of the white pine is easy to work with and to polish, it is also quite resilient. The excellent quality wood fibres make it a stable building material that is not prone to warping and cracking. Furthermore, it floats well and is water resistant. Early settlers quickly discovered the virtues of this species and used it profusely to build houses, farm buildings, furniture, doors, windows, and articles of decoration. The tables, chests, cupboards, and other objects of the daily life of North America's first French settlers were very often made out of white pine and thus, because it was such an integral part of their daily lives, it eventually became a part of their unique cultural heritage.

The resource was abundant and seemed inexhaustible. So what exactly did cause the disappearance of the vast majority of the vast Eastern White Pine stands of the Atlantic coast, the St. Lawrence Valley and the Great Lakes region, within a few hundred years of the arrival of the settlers?

The Fate of the Great Eastern Forest Sealed the Wars in Europe

During the 17th and 18th centuries, timber was essential to the British economy. The impressive fleet of British ships (of the Royal Navy) created an ever-increasing demand for wood to build and repair its vessels. At the time of the first Anglo-Dutchwar (1652-54), the British Empire began to make use of the forest resources of the New England colonies. Realizing that it had a wealth of forest products at its disposal, in 1721, the crown reserved the exclusive right to harvest the white pine forests of its new North American. Some time later, the British government set aside further forestry reserves where the white pine was abundant, including the vast region between Lake Champlain and the St. Lawrence River (Gillis, 1975).

Although, by the end of the 18th century, North Amercian pine was already being harvested in ever increasing quantities, the vast majority of the timber used by the naval industry still came from the Baltic countries. It was only at the beginning of the 19th century that the fate of the Eastern White Pine forests took a radically different turn, due to the escalation of conflicts between the French and the British. Since 1793, French troops had been advancing towards Northern Europe. As a result, in 1806-07, Emperor Napoleon imposed a blockade on the Baltic, thereby depriving Great Britain of its main source of lumber. And so, the British turned to their North American colonies for timber supplies. And so began the destruction of the immense pine forests covering the north eastern part of the continent.

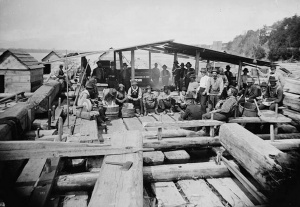

The beautiful white pine stands located along the coast of Nova Scotia were logged rapidly and then Prince Edward Island's pine forests disappeared quickly as well. They were followed by the stands at the edge of the Saint John, Miramichi, St. Croix, Richibucto, Kouchibouguac and other rivers of New Brunswick (Arthur, 1973). The latter were subject to intensive logging operations targeting the finest specimens, leaving only the bare minimum required to meet the timber needs of the local population. The trees were felled and the logs were squared on site, before being transported to be floated downriver to the main seaports where they were loaded on boats that would take them to the other side of the Atlantic. In this way, several thousands of tons of squared timber from New Brunswick was shipped to Great Britain.

A bit earlier, logging operations had made a foray into the Lake Champlain region in search of pine and oak, and it was not long before its white-pine stands were also eradicated. The squared timber was made into rafts and floated down the Richelieu River toward the port of Quebec City or, after the 1819 opening of the Champlain Canal, it was sent south towards the Hudson River to supply the American market.

The vast forests of the upper St. Lawrence region were also exploited, and the logging of the area, which had already been in operation for a few years, started to boom the beginning of the 19th century. The square timber industry expanded at a rapid pace in order to meet the enormous demand coming from Great Britain, which at that time was undergoing industrialization. Until 1810, the port of Quebec City exported square timber in quantities comparable to those shipping from Saint John, New Brunswick, when it suddenly became the hub of the North American timber industry. Hundreds of rafts of pine were floated downstream to the port, broken up and loaded into boats, which left for Liverpool, Bristol, London and the British naval ports. From this time on, the timber industry would surpass the fur trade in Canada. Logging contractors and ship owners made fortunes and the timber harvesting and transporting industry created thousands of new jobs, which would in turn encourage the arrival of new immigrant settlers.

The 1812 war brokes out between the United States and Great Britain, and the number of rafts coming down the Richelieu dropped suddenly. The new areas to be exploited were now the upper St. Lawrence region and the Ottawa Valley, where unbelievably vast, thick stands of pine had been discovered.

The Raftsmen

Pine harvesting in the Outaouais region was an important phase in the history of Canada's logging industry. The region was thickly forested and the region's pine was of exceptional quality. However, since the lumber camps were very far from the port of Quebec City, Outaouais logging operations had to use all sorts of ingenious methods to ensure the port would be kept supplied with plenty of timber. And so the era of the raftsmen began. The square timber was first assembled into small rafts that could be floated down the narrow waterways and structures were built along the streams to insure that the timber could be navigated past the main natural obstacles. Then as the river widened, the rafts were joined together to create larger floating platforms. The combined rafts were so immense that vertible floating villages would be set up for the duration ofthe trip down the St. Lawrence River. Life on these rafts would grow to play an important role in the evolution of popular folklore and traditional music.

A song originating in the Ottawa valley, dating back to the second half of the 19th century. Here is the original French version followed by the English version (NOTE 1):

Les Raftsmen:

Là ousqu'y sont, tous les raftsmen? (X 2)

Dans les chantiers y sont montés.

REFRAIN (après chaque couplet)

Bing sur la ring! Bang sur la rang!

Laissez passer les raftsmen

Bing sur la ring! Bing, bang!

Et par Bytown y sont passés (X 2)

Avec leurs provisions achetées.

En canots d'écorc' sont montés(X 2)

Et du plaisir y s'sont donné.

Des "porc and beans" ils ont mangé (X 2)

Pour les estomacs restaurer.

Dans les "chanquiers" sontarrivés (X 2)

Des manch's de hache ont fabriqué.

Que l'Outaouais fut étonné [Allof Outaouais was amazed] (X 2)

Tant faisait d'bruit leur hach' trempée [At the noise their steel axes made].

Quand le "chanquier" fut terminé [When the logging camp had finished its work] (X 2)

Chacun chez eux sont retournés [Everyone returned home].

Leurs femm's ou blond's ont embrassé [To kiss their wives or lasses] (X 2)

Tous très contents de se r'trouver! [Allso happy to be together again].

The Raftsmen:

The gay raftsmen, oh where are they? (X 2)

To winter camps, they're on their way.

REFRAIN (after each verse)

Bing on the ring! Bang onthe rang!

Hear the raftsmen loudly sing!

Bing on the ring! Bing, bang! (Hey)

Across Bytown they went today (X 2)

They've packed their grub, they cannot stay.

Bark canoes they make their way (X 2)

They reach the camp and shout, "Hurray!".

When meal time comes the men all say, (X 2)

"It's pork and beans again today."

There axes sharp with no delay (X 2)

They swing and strike, the tall trees sway.

The logs they trim and drag away, (X 2)

To drive down when the ice gives way.

In spring they draw their winter's pay (X 2)

And go back home on holiday.

To greet them come their ladies gay, (X 2)

Who help them spend their hard-earned pay!

New Exports

Around 1850, the Baltic nations once again began to supply Great Britain with timber, and more and more iron began to be used for ship building. Demand for North American timber to construct British ships was becoming a thing of the past. At the same time, new markets were opening up, and pine logs were no longer being exported only to the British market, for timber was also starting to be transported to the United States and to other regions of Canada for making cabinets and constructing buildings. It was during this period (1850-80) that the massive logging of the pine forests of the Mauricie and Saguenay regions occurred. Land surveyors were astounded to discover the abundant forests of the Saint Maurice Valley. The forests were thick with white pine, the stands extending from the far north of the St. Lawrence all the way to the Vermillon and Trancherivers (Gélinas, 1984). These stands were rapidly logged with a great deal of waste and little care or concern about the future. So fell the last of the great ancient pine forests of Eastern Canada.

"For instance, a 40-inch log with any sort of defect, such as a bit of rot in the heartwood, a punk knot or a surface crack was left to rot on the site. The Sainte-Flore and Saint-Boniface area remains strewn with these giant trunks, from which hundreds of feet of good sawn planks could have been cut. This wasteful practice lasted until the end of the last century [the 19th], when high-quality pine timber began to be a rare commodity in the Saint Maurice Region." (Boucher, 1952 - original citation translated into English)

From Square Timber to Sawn Lumber

Timber was the cornerstone of Canadian commerce for most of the 19th century. It helped to fuel economic expansion and encouraged increased investmenting, immigration, as well as the creation, growth and development of villages, towns and cities. Practically all of the rivers flowing into the Atlantic Ocean, the Great Lakes and the St. Lawrence River were used for floating timber downriver. Ports of varying importance were constructed at the mouths of rivers.

The years between 1850 and 1875 are considered a transitional period in the history of national forests. By then, all the pine forests of New Brunswick and the Gaspé Peninsula had nearly been exhausted, and a number of forest-management measures were put in place by provincial governments, including the creation of forest concession areas in Quebec and Ontario. The timber market shifted from square timber to sawn lumber. The industrialization process, modest as it still was at this time, had already reached a turning point. Demand for pine and spruce lumber was on the rise and more and more was being milled (seven times more in 1873 than in 1850). On the other hand, the square timber market (95 percent of which was made up of pine) had begun to level off. During the 1865-55 period, the balance tipped in favour of sawn lumber once and for all-fewer and fewer logs of squared timber would be hauled from the public forests (Gaudreau, 1999).

Depending on the region, the change over from squared to sawn timber seemed however to have varied. This can be explained by the fact that timber operations would first cut down the finest specimens to be squared. Per cubic foot, square timber was worth more than sawn timber and so, once the biggest trees were all harvested, then the logging companies would begin harvesting the lower grade specimens to be sent to the sawmills. Since the finest specimens had already been cut, the diameter of the logs arriving at the mills was gradually getting smaller. Slowly but surely pine gave way to spruce.

From 1866 to 1874, American demand for lumber grew by leaps and bounds. The Atlantic coast was urbanizing as the forests of New England were being exhausted. The cities of New York and Philadelphia already had populations of one million and 500,000 respectively. Although more difficult to measure, from this time on, the domestic [North American] demand for timber would constitute a significant part of the market. Thus, the industry was no longer exporting all of the timber to the other side of the Atlantic. The advent of the steam engine (locomotives, boats, etc.) and the coming of the railway would soon facilitate the building of additional sawmills and the shipment of timber to growing regions.

A Fragile Natural Resource and Forestland Heritage in Need of Protection

The lumber industry reached its peak during the second half of the 19th century. Timber companies began to expand and build more and more sawmills, around which boom towns and entire cities were springing up. Such was the case of Hull (Quebec) and Carleton (New Brunswick). The access routes created to facilitate logging operations were soon used for settling new areas. Toward the end of the 19th century, even though the sawmills were still flourishing, the pulpwood industry began to emerge just as the square timber industry collapsed entirely. In the new paper industry, the smaller heartwood billet (log) reigned supreme (Claveau and Laframboise, 1983) and so spruce became the most sought-after species of tree, thereby marking the end of the intensive logging of the white pine forests.

Over a period of only a few short centuries, over three billion cubic metres [3.92 billion cu yds] of pine timber was logged from eastern North American forests. The impact of the logging on the region's forest ecosystems was tremendous and it would appear that the point of no return had been reached a very longtime before. Although today it would seem impossible to restore the white pine to its former glory, preserving the remaining pine forests remains a major challenge for both present and future generations. Significant protection and conservation initiatives will have to be approved if we truly wish to safeguard what is left of this precious natural heritage.

Raymond Quenneville

Fire-management Specialist

Parks Canada

Quebec Service Centre

NOTES

1. The English version of this song is not a translation, but rather two similar versions of the same song. The first half of the song is nearly a translation, but from the fifth verse on, the themes change. There are substantial differences in the last three verses (to compare, see translations in brackets), particularly the difference between the French Canadian cultural theme of the importance of social life and relationships and the English cultural theme of earning and spending hard-earned money. For more information please see: Plouffe, Hélène, "Les Raftsmen", The Canadian Encyclopedia, http://www.thecanadianencyclopedia.com/index.cfm?PgNm=TCE&Params=U1ARTU0002917

Bibliography

Boucher, Thomas, Mauricie d'autrefois, Édition du bien public, Collection Histoire régionale, no. 11, 1952, 206 p.

Claveau, P. et Y. Laframboise, L'exploitation forestière destinée au commerce du bois au 19e siècle, Ethnotech inc., 1983, 443 p.

Gaudreau, Guy, La récolte des forêts publiques au Québec et en Ontario, 1840-1900, McGill-Queen's University Press, Montréal et Kingston, 1999, 173p.

Gélinas, Cyrille, L'exploitation et la conservation forestière au parc national de la Mauricie, 1830-1940, Dossier documentaire, Parcs Canada, Québec, 1984, 460 p.

Lower, Arthur Reginald Marsden, Great Britain's Woodyard, British America and the Timber Trade, 1763-1867, McGill-Queen's University Press, Montreal and London, 1973, 271 p.

Gillis, S.J., The timber trade in the Ottawa Valley, 1806-54, Parks Canada, Department of Indian and Northern Affairs, Manuscript Report no. 153, 1975, 515 p.

Ingall, Mr., Remarques sur le territoire traversé par l'Expédition du Saint-Maurice dans l'été de 1829, Section F (Journal), Ed. Neison & Cowan, Québec, 1830, UQTR microfilmMFM0021.

Additional DocumentsSome documents require an additional plugin to be consulted

Images

-

Le Limeur de Scie

-

Les chantiers Goudie

sur le rivière ... -

Les scieux de long

-

Montréal vue du Saint

-Laurent. extra...