Mount Royal Park, a Precious Natural and Cultural Heritage

par Les amis de la montagne

Between the Laurentians and the Appalachians, the St. Lawrence Plain is punctuated by a series of hills extending from east to west. These Monteregian Hills, as they are known, were formed by intrusions of molten magma over 100 million years ago. One of them, Mount Royal, dominates the largest island of the Montreal archipelago, right in the heart of Quebec's biggest city. This remarkable urban park is subject to equally remarkable protection and enhancement measures. Exploring the mountain’s rich, multifaceted heritage is a perfect way to reconnect with the natural and human history of Montreal and appreciate the charms of its natural and human landscapes, a testimony to ongoing efforts to balance nature and culture.

Article disponible en français : Parc du Mont-Royal, un précieux patrimoine naturel et culturel

A Site with a Rich History

When Jacques Cartier landed on the island of Montreal in 1535, he was met by aboriginal people who had been living there for centuries. It was these Iroquoians from the village of Hochelaga who guided the French explorer to the top of the mountain dominating the island. Impressed by the view out over the vast wooded plain and the St. Lawrence and other surrounding rivers, Cartier decided to name it “Mount Royal.” Of course, the island environment has changed considerably since Cartier’s day, but Mount Royal remains an ideal place to get in touch with nature.

In addition to its natural heritage, Mount Royal has preserved a significant cultural heritage that bears witness to the successive communities that have made the area their home. Trails follow the steep, rocky contours where, amidst a still dense and diverse forest, people out for a stroll pass prestigious institutions and the numerous private residences that line the sides and base of the mountain. Other pathways wend their way through passes and vales to reveal a succession of rich natural and urban landscapes. Two parks were established to protect this exceptional natural environment, and two large cemeteries were also created.

Genesis of a Mountain

For millions of years, the Montreal area lay buried beneath a vast inland sea. Debris and particles in suspension settled to the sea bed, forming deposits that gradually turned into a thick layer of limestone under the pressure of the water and the accumulation of sediments. Then, molten magma from the earth’s mantle pushed upward through the earth’s thin crust without erupting. The magma cooled and stabilized, forming a highly resistant type of rock called gabbro. Over the course of several million years, natural forces sculpted the land. Masses of gabbro emerged from the sedimentary rock, thrust up by the movement and buckling of the earth’s crust. After the sea withdrew, the action of the freeze-thaw cycle, the sandblasting effect of the wind and the grinding of the glaciers gradually eroded the more fragile sedimentary rock. Eventually, the Monteregian Hills that we know today, including Mount Royal, were formed. These rocky protuberances in the middle of the St. Lawrence Plain were ready to welcome new life.

A Remarkable Natural Habitat

Lichens were the first organisms to colonize the naked rock. They paved the way for a succession of life forms: mosses, herbaceous plants, small woody plants, shrubs and trees that, in their turn, eventually made animal life possible.

On Mount Royal, different organisms colonized the habitat best suited to them. Red oaks took root on higher ground, attracted by the dryer, fast-draining soil. The oak stand, with its weakened trunks and large broken branches, testifies to the harsh environment. Acorns from the oaks provided food for animals, who also sought shelter in tree holes and hollows. On the mountain’s steep, rocky slopes, white birches sent forth their roots, whereas lower down, and in small hollows with deeper, more nutrient-rich soil, sugar maples grew. In hollows where water accumulated, swamps welcomed salamanders and other animals and plants adapted to wetland environments. Gradually, a richly biodiverse ecosystem developed over the entire mountain.

Today, Mount Royal’s forests and woodlands are home to over 250 species of vascular plants, including several that are endangered (May-apple) or vulnerable (white trillium, bloodroot), as well as some 60 tree species, 180 bird species, nearly 20 mammal species, 2 types of amphibian, 2 types of reptile and thousands of species of insects.

This plant and animal diversity stands in stark contrast to the surrounding city, with its vast expanses of brick, cement and asphalt. Despite human disturbances, the mountain remains a remarkable place to discover the living organisms that have made it their home for millennia.

The Urbanization of Mount Royal

Until the industrial revolution, the mountain was far enough from the city centre to remain essentially a wilderness. In the early years, Montreal developed along the river, but between 1850 and 1880, the city underwent a dramatic growth spurt, tripling in population to 300,000. A landscape previously dominated by church steeples and orchards gradually gave way to workshops and industries. Workers crowded into housing close to factories and their belching chimneys, while the city’s wealthier citizens, many of them factory owners, began to settle along the edge of Mount Royal in the neighbourhood known as the Golden Square Mile, with a view of the river in the distance. The creation of the Mount Royal and Notre-Dame-des-Neiges cemeteries and the construction of the Hôtel-Dieu hospital, McGill University and the Grand Séminaire de Montréal bear witness to the appeal that the mountain held for health, educational and church institutions.

Olmsted’s Park

At the end of this period of rapid economic and demographic growth, the City of Montreal acquired a large piece of land on Mount Royal’s tallest summit and created a public park for the benefit of all city residents. Planning and development were entrusted to landscape architect Frederick Law Olmsted, who drew up the first park plan between 1874 and 1881. Olmsted had seen rural residents flocking to the city, attracted by the appeal of urban living, but felt that cities did not have enough natural landscapes. In his eyes, access to nature was fundamental to city dwellers’ spiritual, mental and physical well-being. He therefore planned the park to highlight the poetic charms of the natural scenery. In addition, he saw the park as a place where people from every social class could rub shoulders, contributing to democratic life in the city.

In his initial plan, the architect identified and described eight topographic areas and mapped out a network of roads and trails that would showcase this succession of landscapes. He compared the climbing of the mountain to the reading of a poem, with each area serving as a line of verse forming a cohesive whole.

In the end, Mount Royal Park was not built exactly according to Olmsted’s original specifications. Yet it remains an ideal place to enjoy the type of experience its designer intended it for. The park’s natural surroundings and landscapes are an invitation to contemplation, and a sharp contrast with the hectic pace of work, consumerism and urban transportation and construction.

A Great Urban Park

In 1935, the population of Montreal Island topped the one million mark. Early 20th century life was marked by innovations that encouraged urban expansion, both upward and outward—notably the elevator, automobile and tramway. A tunnel was even dug beneath the mountain, and is still used by commuter trains today. Factory chimneys were gradually replaced by high-rises to provide much-needed office space for the fast-growing services sector. The Royal Bank building was the first in the city to exceed the Notre-Dame Basilica in height. Before long, the 26 storey Sun Life Insurance building rose to dominate the urban skyline.

Little by little, the city continued to grow until it almost encircled the entire mountain, making Mount Royal Park a truly urban enclave. This was the period that saw the construction of the Sir George-Étienne Cartier monument, the famous cross and the chalet, as well as the creation of Beaver Lake. Elsewhere on the mountain, the Westmount summit was protected by the creation of Summit Park, while the Royal Victoria Hospital, Saint Joseph’s Oratory and Université de Montréal were being built at the foot of the mountain.

A Modern-Day Park

In the 1950s, as the population of the island neared two million, further transformations occurred on the mountain. A number of antennas were erected, the Beaver Lake Pavilion was built and cars made their appearance—despite protests—with the construction of Camillien-Houde Way and several parking areas. Another lookout was also added on the northeast side. By now, the mountain was completely encircled by the city and high-rise apartments proliferated along its perimeter. Although population growth on the island slowed dramatically during the 1970s as city dwellers flocked to the suburbs, the urban landscape continued to change. Skyscrapers mushroomed, their height limited only by a municipal by-law forbidding any structure from exceeding the elevation of the mountain. In city neighbourhoods, meanwhile, efforts were made to protect mountain views.

The cemeteries in the park and the universities and other institutions along the mountain’s edge continued to expand. Every new project sparked debate over the conservation and enhancement of the mountain’s natural and historic heritage. More than ever, Mount Royal had become an islet within an island—a distinct and separate environment in need of protection.

A Government Order-in-Council and a Protection Plan

In 2002, with the natural integrity of the mountain and Mount Royal Park under increasing pressure, the citizens’ group Les Amis de la Montagne, founded in 1986, organized the first ever Mount Royal Summit. Some 200 people attended the event to discuss which areas needed protection, determine the type of statutory measures required to attain protection and enhancement goals and identify the most appropriate management structure to put in place. The summit also led to the adoption of the Mount Royal Charter, which sets forth, among other things, a shared commitment: “Individually and collectively, we are all guardians of the natural, landscape, architectural and historic heritage of Mount Royal, not only for ourselves but also for future generations.”

Participants at the summit reached the following conclusions: first, the area to be protected must include all three summits; second, special attention must be paid to the green core made up primarily of Mount Royal Park and the two big cemeteries; third, this area must be protected by provincial legislation, but preferably managed by the City of Montreal; and lastly, a formal consultation mechanism must be put in place to facilitate citizen participation and ensure a comprehensive view of the mountain’s development. These conclusions were formally adopted at the 2002 summit, a turning point in the recent history of Mount Royal.

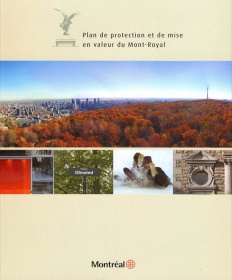

A little over two years later, on March 11, 2005, the government of Quebec officially adopted an order-in-council creating the historic and natural district of Mont Royal. The first and only such designation of its kind in Quebec, it aims to ensure the harmonious development of the mountain’s natural and cultural heritage resources and facilitate the conservation and enhancement of its distinctive features. On the same day, the City of Montreal announced the creation of an issue table—Table de concertation du Mont-Royal—which brought together the mountain’s main institutional landowners, heritage protection associations and elected municipal officials and civil servants. The 60-odd members of the Table were tasked with developing a joint vision for the protection and enhancement of the mountain, notably by updating the Mount Royal Development Plan (dating from 1992). After four years of work and discussions, the Mount Royal Protection and Enhancement Plan was adopted by the City in April 2009. This document became the benchmark for anyone with plans or projects within the limits of the historical and natural district of Mount Royal.

A Look Ahead

The adoption of the protection and enhancement plan marked an important step in Mount Royal’s history. And while the plan seems to have consensus support, its value and effectiveness will depend on the commitment of the municipal and provincial elected officials charged with overseeing its implementation.

The protection and enhancement of Mount Royal’s rich cultural and natural heritage requires ongoing efforts to better understand, care for and improve upon this invaluable resource. Budgets, professional staff and consultation and cooperation structures must be maintained and developed if protection and enhancement efforts are to fully bear fruit. This is the challenge that lies ahead.

Les Amis de la Montagne

In collaboration with Martin Fournier, coordinator of the Encyclopedia of

French Cultural Heritage in North America

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Ballivy, Violaine, « La mémoire de l'eau », Québec Science, mai 2002. « L'eau, une source indispensable à la vie », Ville de Montréal.

Bédard, Pierre, Excursion géologique au mont Royal. Département des Sciences de la terre, Université du Québec à Montréal, automne 1998, 17 p.

Centre de la montagne, Carte - le mont Royal au fil des saisons, 1997. Coordination, Joanne Groulx ; recherche, conception et rédaction, Tom Berryman ; conseils, Jean-Yves Benoit, Daniel Chartier, Nicole Gagnon, Éric Richard, Paul Rioux.

Foucault, A., et J.-F. Raoul, Dictionnaire de géologie, 3e édition, Paris, Masson, 1992, 352 p.

Les amis de la montagne, Les forêts du mont Royal, 2008-2009.

Pinard, Guy, Montréal, son histoire, son architecture, Éditions La Presse, 1986-89, tome 3. Tome 6, éd Méridien, 1995.

Additional DocumentsSome documents require an additional plugin to be consulted

Images

-

Affichette du Mois du

Affichette du Mois du

Mont-Royal 200... -

Belvédère Kondiaronk,

2008 -

Cardinal du Mont-Roya

Cardinal du Mont-Roya

l, 2009 -

Carte postale ancienn

e montrant la r...

-

Cassure cornéenne, Mo

nt-Royal, 2008 -

Chênaie rouge, Mont-R

oyal, 2008 -

Cimetière du Mont-Roy

al, 2009 -

Cimetière juif, sect

ion des communa...

-

Colvert en milieu hum

ide, Mont-Royal... -

Construction du stati

Construction du stati

onnement près ... -

Couleuvre au Mont-Roy

Couleuvre au Mont-Roy

al, 2008 -

Densité urbaine à Mon

Densité urbaine à Mon

tréal, 2008

-

Densité urbaine à Mon

tréal, 2008 -

Effets de la crise du

Effets de la crise du

verglas de 199... -

Érablière à sucre, Mo

Érablière à sucre, Mo

nt-Royal, 2008... -

Feuilles d'érable à s

ucre, Mont-Roya...

-

Fontaine de la rédemp

Fontaine de la rédemp

tion, oratoire ... -

Fougeraie, Mont-Royal

, 2008 -

Frederick Law Olmstea

Frederick Law Olmstea

d -

Grand pic, Mont-Royal

, 2009

-

Junco ardoisé, Mont-R

Junco ardoisé, Mont-R

oyal, 2007 -

Le Mont-Royal, 2010

Le Mont-Royal, 2010

-

Mésange à tête noire,

Mésange à tête noire,

Mont-Royal, 20... -

MUHC Allan Memorial H

ospital, 2008

-

Nerprun cathartique,

Nerprun cathartique,

Mont-Royal, 200... -

Phasme, Mont-Royal, 2

008 -

Pic flamboyant, Mont-

Pic flamboyant, Mont-

Royal, 2009 -

Plan du parc du Mont-

Plan du parc du Mont-

Royal en 1877

-

Promeneurs dans le pa

rc du Mont-Roya... -

Raton laveur, Mont-Ro

Raton laveur, Mont-Ro

yal, 2008 -

Renard roux, Mont-Roy

Renard roux, Mont-Roy

al, 2008 -

Roches calcaires, Mon

t-Royal, 2008

-

Sanguinaire, Mont-Roy

al, 2008 -

Sentier du chemin Olm

stead, Mont-Roy... -

Sentier du parc Summi

t, Mont-Royal, ... -

Souris sylvestre, Mon

Souris sylvestre, Mon

t-Royal, 2008

-

Tamia rayé, Mont-Roya

l, 2009 -

Tilleul en hiver, Mon

Tilleul en hiver, Mon

t-Royal, 2008 -

Tramway, Mont-Royal,

Tramway, Mont-Royal,

1959 -

Trilles au parc Summi

Trilles au parc Summi

t, 2008

-

Voie Camilien-Houde s

Voie Camilien-Houde s

ur le Mont-Roya... -

Vue aérienne de l'ens

Vue aérienne de l'ens

emble du Mont-R... -

Vue aérienne du campu

Vue aérienne du campu

s de l'Universi... -

Vue aérienne du cimet

Vue aérienne du cimet

ière du Mont-Ro...