The French Canadian Contribution to the Lewis and Clark Expedition: Taking the Measure of a Continent

par Vaugeois, Denis

There are hundreds of books telling the story of the Lewis and Clark Expedition, tasked by President Thomas Jefferson with finding “direct & practicable water communication across this continent, for the purposes of commerce.” For Americans at that time, the area west of the Mississippi was terra incognita. French Canadians, on the other hand, had been traveling the region since the beginning of the 18th century. Indeed, the Jesuit Father Charlevoix had visited Kaskaskia, Cahokia and Natchez as early as 1721, and was of the firm opinion that the Missouri River led to the western ocean.

Saint Louis, a small settlement at the mouth of the Missouri, would be Lewis and Clark’s starting point. There they recruited French Canadians familiar with the river to act as guides, pilots, interpreters and hunters. These French Canadians were the unsung heroes of an expedition that could not have succeeded without them. Lewis, for example, never took any significant action unless accompanied by Georges Drouillard, described as “a man of much merit” in his journals upon the expedition’s return. There is no question that the Lewis and Clark Expedition constitutes an episode in the history of French North America.

Vital French-Canadian Expertise

The first European explorers saw America as a barrier on the route to the Indies. Christopher Columbus, using Ptolemy’s calculations, had underestimated the earth’s circumference by 12,000 km, which is why he thought he had arrived in India. Thus, for Columbus, the people he met were Indians; the corn he found, Indian wheat (still reflected in the French, blé d’inde); the turkey, “Indian fowl” (poule d’inde, which evolved into the French word, dinde). When it became apparent that he had in fact landed on a hitherto unknown continent, another misunderstanding occurred: geographers in Saint-Dié-des-Vosges, France, credited Amerigo Vespucci with the discovery. Thus “America” became a continent along with Europa, Asia, and Africa.

Despite America’s riches, Europeans, including Samuel de Champlain, remained focused on finding a western passage. French explorers soon identified and took control of the principal gateways to North America: the Saint Lawrence and Mississippi rivers and Hudson Bay. They also planned to capture New York at the head the Hudson River, another potential route to the West. At the beginning of the 18th Century, North America was essentially under French control.

Over the centuries, hundreds of voyageurs, trappers and explorers from New France criss-crossed North America to trade furs, conduct official missions or seek adventure. The beaver hat craze helped fuel and finance these voyages of discovery. Mutual interest made for friendly contact with Indians. Throughout the Saint Lawrence River Valley hinterland, cultural and genetic métissage became the norm.

The French who adopted and adapted to Canada became known a Canadiens (later French Canadians). Though few in number, they were everywhere. Travelers’ narratives all tell the same tale: the author ventures forth, sure of charting new territory, only to meet humble French Canadians in even in the most remote backwaters.

The British Conquest of 1763 checked the momentum of French Canadian expansion without bringing it to a halt. Most French Canadians fell back on farming or small trade, although a good number refused to be confined within the borders of the new “Province of Quebec.” Many had already established themselves in the fur-trading territory known as the Pays-d'En-Haut, which stretched along the Wabash River (then the “Ouabash”) in Illinois territory and straddled both banks of the Mississippi.

The Mississippi Border and Westward Expansion

Independence found most Americans still looking toward the Atlantic, but the most intrepid among them already had their eyes on the vast territory west of the Appalachians. These settlers would found Kentucky, Tennessee and Indiana and naturally, they wanted to use the Mississippi River for trade and communication. Under the terms of the 1763 Treaty of Paris, terms renewed in 1783, navigation on the Mississippi was, in theory, free to all. However, the border, despite widespread misconceptions that persist to this day, did not follow the Mississippi from its source to its mouth. There were two reasons for this: first, the source had not yet been discovered; and second, the French had successfully negotiated to have the southern border depart from the Mississippi and follow the smaller d’Iberville River and lakes Maurepas and Pontchartrain. In this way, they were able to keep New Orleans . From the mouth of the d’Iberville River (30º latitude) to the Gulf of Mexico, the banks of the Mississippi were thus occupied by a foreign power.

But even though the French had negotiated the terms of the Treaty of Paris, especially article 7, the main beneficiary was Spain, which had inherited this part of North America under the November 1762 Treaty of Fontainbleau. Settlers to the west of the Appalachians had developed an understanding with the Spanish and used the Mississippi as far as the Gulf of Mexico, as the d’Iberville was not really suitable to navigation.

Upon taking power, Napoleon set his sights on the Antilles and asked Spain to return the concessions granted at Fontainebleau in 1762. He wanted to use the continent, and New Orleans in particular, as a base of operations. News of the plan alarmed the Americans, especially in Kentucky, Tennessee and Indiana. They were certain that their right to travel freely and collect duties would be jeopardized.

President Jefferson took the situation seriously, especially since inhabitants of the lands between the Appalachians and the Mississippi were threatening to secede. He sent emissaries to Paris to negotiate the purchase of the city of New Orleans. Jefferson may have been an avowed francophile, but he was nevertheless willing to launch a military operation and made it clear that he considered the matter a legitimate casus belli.

In response, Napoleon, fresh from a humiliating military defeat in Santo Domingo, made a snap decision to bestow a generous gift upon the Americans, ceding a huge swath of territory in what historians have dubbed the Louisiana Purchase. Was he trying to secure an ally in the fight against the British, creating a force to be reckoned with? In truth, there is no readily apparent reason for such an irrational decision. Jefferson, the visionary, was taken aback. In his mind, the West ended at the Mississippi; beyond lay a territory to be crossed, but not possessed. Since the voyages of Robert Gray and George Vancouver, Jefferson had known that the mouth of the Columbia River was situated at 124º west longitude, i.e. around 5,000 km from Washington (77º west longitude). The brilliant self-taught president conceived of the continent as being symmetrical in shape, with the sources of the Columbia and the Missouri located reasonably close together.

Preparing the Lewis and Clark Expedition

No sooner was Jefferson elected President—a process that nonetheless took 36 rounds of voting!—than he decided to fulfill his old dream of finding a passage to the Pacific. He recruited a young soldier, Meriwether Lewis, who had previously volunteered for a westward expedition. One can well imagine the two men in that the summer of 1802, poring over Alexander Mackenzie’s journals. Mackenzie had succeeded in reaching the Pacific in 1793, but a navigable route had yet to be found. There was no time to lose. Lewis busied himself with lessons of all sorts as well as with material preparations. As he began to appreciate the scope of the undertaking, Lewis decided to approach his friend William Clark and ask him to share leadership of the expedition. The two made a formidable pair, but would not have been able to successfully see the expedition through on their own.

The French had long believed that the Missouri River might be a possible route to the western ocean. The more perceptive among them had even grasped that the Missouri was in fact the continuation of the Mississippi, noting that at the mouth of the Missouri, the Mississippi’s character changed abruptly, becoming “choppy and silty,” as one of Lasalle’s men put it. Had the Europeans arrived from the west, the upper Mississippi would have been considered a tributary of the Missouri, and not vice versa.

The Missouri flowed through what had been, since the 1762 Treaty of Fontainbleau, Spanish territory. In other words, the Americans required permission to explore it. Jefferson approached Spanish authorities outlining the expedition’s scientific and commercial objectives. The Spanish Ambassador found Jefferson to be “hungry for glory” and recommended denying passports. In the end, it was Napoleon’s decisions to cede not only New Orleans but the entire Mississippi River basin to the United States that settled the matter.

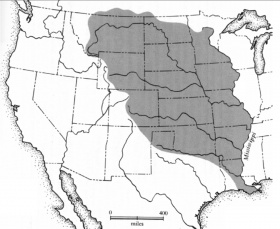

For many, the “Louisiana Purchase” evokes the modern-day state of the same name. In fact the area sold by Napoleon was much bigger than that, so big that it doubled the existing land area of the United States. Jefferson quickly realized just how important this purchase was, although he still had little idea what it would be used for. He imagined that the explorers signing up for the expedition would be travelling into prehistory, and might even encounter woolly mammoths. But he also understood that the source of the Mississippi and its tributaries would henceforth constitute the United States’ northern border. He asked Lewis and Clark to find the northernmost point of the Mississippi River Basin, reasoning that it might be different from the actual source of the river. Jefferson’s intuition proved well founded: The source of the Milk River is at 49º north latitude whereas the source of the Mississippi, Lake Itasca, is near the 47th parallel.

The Louisiana Purchase was finalized in the summer of 1803. Lewis, who was in Pittsburgh at the time awaiting the completion of his custom-built boat, was held up. While he complained of the boat builder’s drunkenness, the resulting delay would indirectly ensure the expedition’s success by pushing back the expedition’s whole schedule. In 1804 residents of Saint Louis looked on as the Spanish flag was replaced by the French tricolour. At the request of the townsfolk, most of whom were French, the French flag was allowed to fly until the next day, to be replaced by the Stars and Stripes. In 48 hours, the final chapter in the drawn-out diplomatic manoeuvring between France, Spain and the United States came to a close.

As a result of the transfer, Lewis and Clark would be traveling in American territory, at least as far as the source of the Missouri. For the Americans, these parts were truly terra incognita. The surprises began upon their arrival in Saint Louis. Jefferson had instructed Lewis to encourage any white settlers encountered west of the Mississippi to return to the east. However, not only were there white settlers at the mouth of the Missouri, but most of them spoke French. Following the British conquest of 1763, French settlers from east of the Mississippi had crossed over to the western side where they founded Cap Girardeau, Sainte Geneviève and Saint Louis.

Lewis and Clark spent the winter of 1803–04 preparing for their adventure. They studied other maps complementing the Arrowsmith map that Jefferson had provided. And they recruited Georges Drouillard, a Métis born of a French Canadian father, while en route to the Mississippi. The expedition’s success would rest on Drouillard’s shoulders. Knowing the challenges the Americans would face, he convinced them to expand the expeditionary team, up to then composed exclusively of soldiers and Clark’s black slave. Three boats were to be used: one keelboat and two prirogues. One pirogue was entrusted to eight French-Canadian engagés, or hired boatmen: Charles Hébert, Jean-Baptiste Lajeunesse, LaLiberté, Étienne Malboeuf, Pierre Pinaut, Paul Primeau, François Rivet and Pierre Roy, under the leadership of Baptiste Deschamps. The other pirogue, manned by soldiers, was under the command of Corporal Richard Warfington. Two Métis, Pierre Cruzatte and François Labiche, also joined the expedition. Born of Omaha mothers, Cruzatte and Labiche were both intimately acquainted with the dangers of navigation on the Missouri. They would take turns at the keelboat’s helm, and serve as hunters and interpreters until the expedition reached Fort Mandan. While Lewis carried a large air rifle to impress the Indians, Cruzatte and his fiddle probably had more impact. These three Métis—Cruzatte, Labiche and Drouillard—would make all the difference to the expedition’s success.

A Francophone Terra Incognita

The expedition had scarcely left Saint Louis when Lewis and Clark found themselves struggling with French names. Their instructions were to record everything. The difficulties began in the neighbouring village, Saint Charles, where they found a hundred-odd families “descendant of the Canadian French.” As Lewis noted, “It is not an inconsiderable proportion of them that can boast a Small dash of the pure blood of the aboriginies of America.” In Saint Charles, Lewis caught up with Clark, who had gone ahead to finish loading the boats. On May 21, 1804, the expedition team set off for real to the cheers of curious onlookers lining the banks. They would not return until September 21, 1806, all safe and sound, save for one officer who had fallen victim to illness.

Saint Charles is better known under “the appellation of petite Cote,” Lewis noted, more or less resigning himself to meeting one French name after another. He observed that the settlers had little interest in farming and were under the dominion of a Catholic priest. The next stop was La Charrette—LaCharatt in Clark’s spelling; Chouritte in Lewis’s. Names were sometimes translated, sometimes written in approximate spellings. Both captains’ renderings of the names of the expedition’s “Frenchmen”—as they called them—were creative to say the least. Baptiste Deschamps becomes Battist de Shone; Lajeunesse appears as Lasoness; even as valuable a member as Labiche is misspelt La Beiche, Labuche or Labuish. The hero of the expedition, Georges Drouillard, most often appears as “Drewyer” and sometimes as Drullier or Drulyard. This was the norm for all the francophones, to the point where on first reading the journals of Lewis and Clark and their officers, it is easy enough to overlook their existence, let alone the scope of their contribution.

In La Charrette, the last white post, the Americans met Régis Loisel, a successful trader who would provide them with vital information. Lewis noted that “Louissell” informed him that there were no Indians until the Ponca River in Sioux country. Here, then, is another surprise for readers of Lewis and Clark’s journals: during the first two months, the expeditionary corps met not a single Indian.

The smallpox brought by Europeans had devastated the area. At the beginning of August, Lewis found himself at the burial grounds of Black Bird, an Omaha chief who had fallen prey to the disease along with 400 of his people. There, a Frenchman referred to as Fairfong, living with his family among the Indians, brokered a meeting with the Otto and Missouri tribes (the latter had taken refuge with the Otto after being decimated by smallpox). The expedition recorded the devastation wrought by smallpox on various Indian tribes, including the Mandan and the Arikara, whose settlements had mostly disappeared.

As it proceeded up the Missouri, the expedition repeatedly encountered French Canadians, invariably referred to as “Frenchmen.” Three of them, Pierre Dorion, Joseph Gravelines and Jean Vallée, would lend valuable assistance. Indeed, Lewis and Clark had learned a lesson: they would need an interpreter. In Fort Mandan, they hired Toussaint Charbonneau and his Shoshone wife, Sacagawea.

The Expedition that Founded a Nation

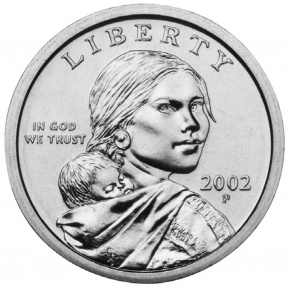

The Lewis and Clark expedition is an American foundation myth. The expedition has inspired thousands of works and brought great renown to its members. Sacagawea is undoubtedly commemorated by more monuments than any other woman. Along with her son, Jean-Baptiste Charbonneau, she even has her place on an American dollar coin.

For the expedition’s centennial, Reuben Gold Thwaites published a remarkable new edition of the journals of Lewis and Clark and their officers. Thwaites, who also brought out an edition of the Jesuit Relations, knew French America well and recognized the important French Canadian contribution to the expedition’s success. But Thwaites’ effort was not to be the final chapter. In honour of the expedition’s bicentennial Gary Moulton oversaw a team of leading scholars who produced a twelve volume edition in which the expedition’s French Canadians figured less prominently.

It comes as no surprise that the Indian contribution receives even more cursory treatment. Yet Indians not only granted safe passage to the expedition, they also actively came to its rescue. The journals of Lewis and Clark still contain untold stories, particularly those of the humble and unheralded people who made the expedition possible.

Denis Vaugeois

Historian

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Chaloult, Michel, Les « Canadiens » de l’expédition Lewis et Clark, 1804-1806 : la traversée du continent, Sillery, Septentrion, 2003, 189 p.

Vaugeois, Denis, America 1803-1853 : l’expédition de Lewis et Clark et la naissance d’une nouvelle puissance, Sillery, Septentrion, 2002, 263 p.

Additional DocumentsSome documents require an additional plugin to be consulted

Images

-

Carte de l'expédition

Carte de l'expédition

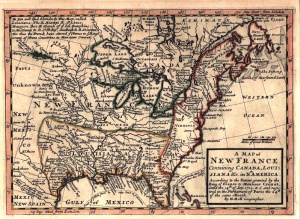

de Lewis et Cl... -

Carte de la Louisiane

Carte de la Louisiane

et du cours du... -

Carte de la Nouvelle

Carte de la Nouvelle

France contenan... -

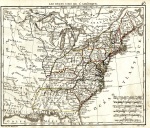

Carte des États-Unis

Carte des États-Unis

d'Amérique, 180...

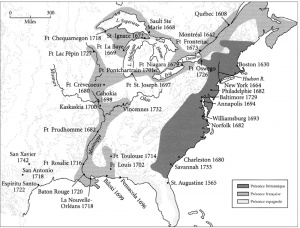

-

Carte montrant la pré

Carte montrant la pré

sence française... -

Carte particulière de

Carte particulière de

s embouchures d... -

Carte présentant cert

Carte présentant cert

ains repères gé... -

Dollar américain mont

Dollar américain mont

rant Sacagawea ...

-

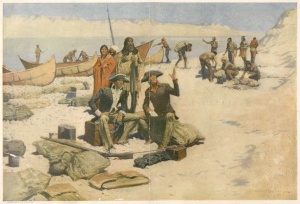

Expédition de Lewis e

Expédition de Lewis e

t Clark (1804-1... -

Expédition de Lewis e

Expédition de Lewis e

t Clark (1804-1... -

Indiens Mandan

Indiens Mandan

-

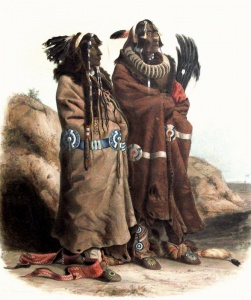

Indiens Missouri, 184

Indiens Missouri, 184

0-1843

-

Indian Life: A Mandan

Indian Life: A Mandan

Cabin -

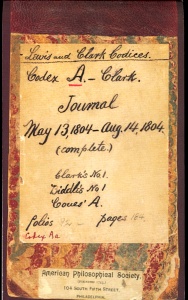

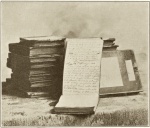

Journal de William Cl

Journal de William Cl

ark, 13 mai au ... -

Journaux originaux de

Journaux originaux de

l'expédition d... -

Le territoire de la L

Le territoire de la L

ouisiane que cè...

-

Murale du Missouri St

Murale du Missouri St

ate Capitol évo... -

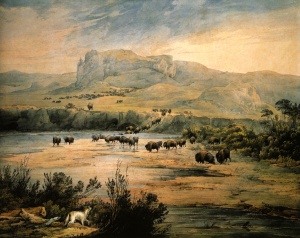

Paysage du haut Misso

Paysage du haut Misso

uri -

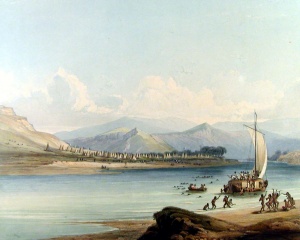

Voyage sur le Missour

Voyage sur le Missour

i (1843) -

William Clark (1770-1

William Clark (1770-1

838)