French-Canadian Trappers of the American Plains and Rockies

par Villerbu, Tangi

The bicentennial celebrations of the expedition led by Lewis and Clark from St. Louis (on the Mississippi) to the mouth of the Columbia River (on the shores of the Pacific) took place in the United States in 2004-2006. The festivities revived interest in this period of history and resulted in a closer look at the situation that prevailed in the western part of the North American continent at the turn of the 19th century. The resulting research revealed two things: that there had been a considerable number of French-speakers in the region at the time of the expedition and that, historically speaking, their presence had received scant recognition. French speakers Toussaint Charbonneau and George Drouillard, who accompanied and guided the expedition, were among the most notable figures whose true role in history finally obtained recognition. Further nearly forgotten historical figures also began to emerge from the shadows: names such as René Jusseaume, Pierre Dorion, Joseph Garreau and so many more-all of whom Lewis and Clark's Corps of Discovery had encountered among the Amerindian tribes with whom they traded for furs on the shores of the Missouri.

Article disponible en français : Trappeurs francophones des Plaines et des Rocheuses étatsuniennes

The Era of the Fur Trade

There is little trace left of what was once the driving force of the economy of the vast interior regions of the American Plains and the Rockies. Starting with the arrival of the Europeans up until the mid-19th century, the dominant commercial activity in the region was without a doubt the fur trade. Although signs of this activity have not been completely erased, the trappers and their trade are no longer considered to be a major part of the contemporary identity of the West-particularly since this part of history has been relegated to an almost imaginary, very distant past. The greatest remaining legacy of the historical impact that this economic activity once had lives on in the forts managed by the National Park Service. Thus, the fur trade continues to benefit the region by way of heritage tourism. Four sites are managed by the parks service: Fort Laramie (Wyoming), Fort Union (North Dakota), Bent's Old Fort (Colorado) and Fort Vancouver (Oregon). All four were private trading posts and regional commercial centres. The problem here lies in the fact that the American conquest of the West in the 19th century transformed a region once characterized by fluid, multiple identities into a "nationalized" space where an exclusively American identity was established and affirmed.

Not only did the establishment of each fort take into consideration the geopolitical context of the various Amerindian nations that inhabited the vast region, but they are also reflective of the diversity of European culture that settled the West. Fort Bent had links to the Hispanic Southwest; Fort Union, with the area of the Plains occupied by the British; and Fort Vancouver, was built by the Hudson Bay Company. The French-speaking community did leave a clear mark on each one of these sites, and recognising their influence would eventually lead to establishing a multi-cultural perspective of the history of the North American West and thus, to re-writing the collective memory of the region.

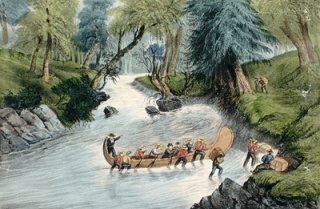

The fur trade in the West-whether in the region beyond the Great Lakes and the Mississippi or the trade established on the Great Plains and later in the Rockies-it all largely originated with French-speaking voyageurs and explorers, Their various east-west incursions, including La Vérendrye's operations out of the St. Lawrence Valley, as well as those of the French settlers residing in the Illinois country, near the Arkansas and the Missouri Rivers. As a whole, the expansion nevertheless remained very tentative until the last quarter of the 18th century, when the fur trade exploded. The industry eventually reaching its peak in the 1830-40 period, well before other forms of colonization came to dominate the region.

Starting in the 1770s, the Hudson's Bay and North West companies (both British, with the former based in London and the latter in Montreal) firmly established themselves in the various British possessions and to the south (particularly along the Upper Missouri River and in the Oregon Country). The activities of the various Spanish establishments along the Missouri River (starting at St. Louis) were less assertive. In this particular region, Canadian traders from the Illinois territory spearheaded the development of the fur trade, but their activities never reached the scope of the British operations. The large American companies that would eventually develop the region, led by the American Fur Company, did not really become established until after the War of 1812. In the American Southwest, the establishment of a real infrastructure took even more time, and so small private operations would have the upper hand in the region until Fort Bent was established in the 1830s.

French Canadian Trappers

Fur companies were structured hierarchically and staffed by a highly varied personnel, which formed a microcosm of the initial wave of colonization (of a non-settled variety) in the interior of the North American continent. More often than not, such firms were headed by English speakers, as was the case in both the British and the American possessions after 1815. Nevertheless, the "French" were on the scene in large numbers as well. William Swagerty calculated that of the 3,000 Rocky Mountain "trappers" (a generic term including all levels of hierarchy), 25.7% were Franco-American or French Canadian (15% were of other European descent). This statistic can be further broken down into four distinct groups, each which represents one form of French culture or another.

The first of these groups, the French-Canadians, were most often hired by the British companies and followed their employers to the south [implies all possessions in today's American interior]. René Jusseaume, whom Lewis and Clark met among the Mandan in 1805, was one of these French-Canadians, as was Charles Chaboillez, a Montreal native and senior manager with the North West Company based in the Red River region. At the time (1806) he was on an expedition to the Upper Missouri Territory. Further west, communities of Canadian origin-offshoots of the fur trade-were established in the Willamette Valley, located in present-day Oregon.

Furthermore, there were the settlers of French-Canadian origin operating in the Illinois country. They plied the Missouri River and other tributaries of the Mississippi deeper into the South, seeking additional fur-trading opportunities. The Chouteau family is a good example of the success of the St. Louis-based entrepreneurs, as does the Céran St-Vrain who is mentioned later. It must also not be forgotten that there were a large number of subordinates, regular, employees from both small and large companies, as well as the self-employed, all of whom worked to assure the day-to-day operation of the fur-trading industry. In the last decade of the 18th century, Jacques d'Eglise, Pierre Dorion, Pierre-Antoine Tabeau, Joseph Gravelines, Jean-Baptistes Meunier, Joseph Ladéroute, and Pierre Berger were all involved in operations along the Missouri, as were literally hundreds of others during the decades that would follow. These are characters who have all long disappeared without a trace, except for their names written in various ledgers-the only written record left in a world where illiteracy reigned supreme.

An additional group should also factored into the equation, a smaller number that nonetheless important: the native-born, second-generation French. Their story differs considerably, given that they were sometimes more educated and could therefore leave a written record of their activities. Both Francis Chardon, born in Philadelphia, and Charles Larpenteur were involved in the fur trade during its heyday in the 1830-40 period. Larpenteur was a native of the Fontainebleau area who followed in his father's footsteps and became a trapper. His father, who had been a Bonaparte supporter, had immigrated to the New World following the events of Waterloo.

The French-speaking trappers differed from their American and British counterparts in that they worked more closely with the Natives that were involved in the trade. As a consequence, they were more willing to establish alliances with native communities through intermarriage. This practice gave birth to a fourth category: the Métis, whose lengthy and complex ethnic and cultural origins made it necessary for them to assert the uniqueness of their distinct cultural identity during the second half of the 19th century.

The Trappers Immortalised in Works of Fiction

At first glance, there seems to be no real reason to romanticize the history of the trappers. Their reality straddled two different worlds where it was necessary to constantly reinvent oneself, in order to adapt to ever-changing social roles and social networks, as they shifted from their own culture to integrate into another. This very fact of the trappers' existence makes them representatives of the world that existed before nationalist rhetoric in all its forms had emerged (or was imposed) in the West. Be that as it may, they were also aware of being instrumental in bringing about the gradual integration of the Plains and Rockies into a world economy that clearly revolved around Western civilisation. In general, they were neither outsiders nor capitalists, but rather they represented an initial phase of colonization. This explains why they disappeared from the scene when the colonising process began to evolve, particularly when trading with the Amerindians gave way to eradicating them in order to make way for settling the territory with European-Americans.

This

fading into history is in fact at the very roots of the movement that enshrines

trappers as heroic figures from a past that had long become the stuff of

legend-a legend that is set in a mythological Far West that predates the United

States itself. This cultural legacy was first evoked in the 1830s by the

authors of some of the earliest American writings, namely those of James

Fennimore Cooper and Washington Irving. In these early texts, any record or

evidence of the role of French-speakers during the trapper era was simply just

brushed aside-just as it would be in the profusion of "dime novels" that were

published later throughout the 19th century. The role of the French

was however a prominent feature of French Westerns-a literary movement that

began to emerge in the late 1840s with the publication of Gabriel Ferry's

novels and rose to fame with the works of Gustave Aimard.

Born in Paris in 1818, Gustave Aimard became a sailor, and then later deserted in Chile (1839). Between 1856 and his death in 1883 he published 88 novels, most of them set in the American West. What is interesting to not is that Aimard's West is not same as that of the Americans, for Aimards works described the region before establishment of national boundaries. In his books the region is a meeting place for various cultures-both Amerindian and European-in which no group (except the Americans) attempted to impose itself by force. The trappers play an essential role in these novels, particularly as they are emblematic of the Western utopia depicted by Gustave Aimard. As such, they are never English speakers, but rather French Canadian (Balle-Franche, Michel Belhumeur), immigrant French (Valentin Guillois, Charles-Edouard de Beaulieu), or Métis (the Berger family). Moreover, they do not work for any company and are thus totally independent of British or American interests. In a sense, they are refugees who have found a haven in the West after having lived difficult lives-particularly as is the case of Beaulieu: "Europe became a hateful place for him and he resolved to leave it for good" (Balle-Franche, 1861, translation).

According to Aimard, the Plains and Rockies appear to be a place where a French-speaking North America could flourish without the restrictions of government, face to face with nature and God. The legacy of Aimard's novels is however double-edged: on the one hand, mass produced editions of his works were being reprinted in France until the end of the 1970s and today they are still being published as a sort of vintage period relic. As a result of these mass-produced works the survival of the French-speaking trapper as a historic figure has been ensured through Aimard's literature. On the other hand, Aimard's literary efforts were rather an isolated case and thus doomed to fail, particularly since his interpretation of the history of Western expansion was quickly drowned out by the highly "nationalist" American version from which the "others" were excluded. After World War I, his novels were given the Hollywood Western treatment, being adapted for screenplay, but with the exception of Howard Hawk's The Big Sky (an adaptation of La Captive aux Yeux Clairs), the involvement of the French voyageurs in the fur trade was by and large absent from the silver screen.

A Scholarly Perspective

Nevertheless, the French trappers' contribution to the history of the West has been granted a certain amount of recognition in some circles in the U.S. American history is not without its own scholars and collectors. At the beginning of the 20th century, their focus turned in part toward the early history of the Far West, particularly to the fur trade, the Age of Exploration and the Westward expansion Movement-all major components in the historical foundation of the country. As a result of this return to the historical basics, Elliott Coues and then Herbert Eugene Bolton, Anne Heloise Abel and LeRoy Hafen rediscovered written accounts from the early days-all which dated from the end of the 18th and beginning of the 19th centuries. In these accounts, French speakers played a definite historical role in the evolution of American cultural heritage. These French speakers however seldom made themselves heard since most of them were involved in the fur trade and, like most of their counterparts, they were illiterate and therefore, they left no written record of their activities. And so, for the most part, French speakers only appear in English language accounts of the era. In a recent study of Canadian trappers, Carolyn Podruchny reveals that there is but one surviving letter written by a French trapper to his family. The same holds true of French speakers in the United States. The accounts provided by English speaking managers of the fur trade are however filled with the names and activities of the "French."

Nevertheless, the writings of a few higher-ranking French-speaking traders were published. The accounts of Pierre-Antoine Tabeau, Charles Larpenteur, and Francis Chardon-to name a few-are all now considered to be classic sources of the history of the period. The lack of accounts written by French speakers raises yet another problem. Since, for many years, the texts of these French speakers were published in conformity with the American view of the history of the Far West, the French fur traders were assimilated into a part and perspective of history that was not their own. As a result, their texts were translated and only published in English-language editions intended for American historians (Larpenteur published his memoirs directly in English). More often than not, the reader is denied the opportunity to read an account of life in the West written from the point of view of the early French-speaking explorers and voyageurs, the trailblazers of pre-American history. During the bicentennial of the Lewis and Clark Expedition, French names were allowed to re-emerge in the historical accounts published for the event, but this clearly did not change the basic order of things-particularly since the celebrations were above all else quite "nationalist", focusing on the two American officers who headed the Corps of Discovery.

Nevertheless, it is still a distinct possibility that, one day, a sort of "rediscovery" of the French cultural contribution to the history of the Missouri Valley and the Rockies will take place. In Quebec, over the last few years, there has been renewed interest in this page of French North American history. However, given that in most people's minds the coureur de bois has long been associated with the Great Lakes and the French colonial era or with that of the Canadian West during the reign of the British companies, rekindling interest and changing perceptions has not always been easy. In 2002 and 2003, two works were published that took a closer look at the French-Canadian involvement in Lewis and Clark's expedition. Then, in 2006, something exceptional occurred: a French-language document from the early fur-trading days surfaced as the main topic of a scientific publication. The featured document consisted of two texts by a Montreal-born resident of St. Louis, one Jean-Baptiste Trudeau, who was sent by the Compagnie du Missouri (a short-lived Franco-Spanish enterprise) to travel up the Missouri in 1794-96 with a group of French speakers. This was a breakthrough for those desirous of seeing the history of Missouri River region, as well as that of the post-1763 Rocky Mountains, presented in the broader perspective of a more multi-cultural North America. Nevertheless, the day that the true history of all the peoples on this wide continent will be told in all its fullness remains yet a long way off.

Tangi Villerbu

Maitre de

conferences [Associate professor] Université de la Rochebelle

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Abel, Annie Heloise (ed.), Chardon's journal at Fort Clark, 1834-1839, introduction and notes by Annie Heloise Abel, introduction to the Bison Books edition by William R. Swagerty, Lincoln, University of Nebraska Press, 1997 (1st edition: 1932), 458 p.

Abel, Annie Heloise (ed.), Tabeau's narrative of Loisel's expedition to the upper Missouri, edited by Annie Heloise Abel, translated from the French by Rose Abel Wright. Norman, University of Oklahoma Press, 1939, 272 p.

Chaloult, Michel, Les « Canadiens » de l'expédition Lewis et Clark, 1804-1806 : la traversée du continent, Sillery, Septentrion, 2003, 189 p.

Coues, Elliott (éd.), Forty years a fur trader on the upper Missouri; the personal narrative of Charles Larpenteur, 1833-1872, textual criticism edition by Elliot Coues, New York, F. P. Harper, 1898.

Hafen, LeRoy R. (ed.), French fur traders and voyageurs in the American West, text selection and introduction by Janet Lecompte, Lincoln, University of Nebraska Press, 1997, 333 p. [The text is a compilation of entries selected from a larger dictionary dating from 1965-1972.]

Lansing, Michael, "Plains Indian women and interracial marriage in the Upper Missouri trade, 1804-1868", Western Historical Quarterly, vol. 31, no. 4 (winter 2000), p. 413-433.

Podruchny, Carolyn, Making the voyageur world : Travelers and traders in the North American Fur trade, Lincoln, University of Nebraska Press, 2006, 414 p.

Swagerty, William, « Marriage and settlement patterns of Rocky Mountains trappers and traders », Western Historical Quarterly , vol. 11, no 1 (spring 1980), p. 159-180.

Trudeau, Jean-Baptiste, Voyage sur le haut-Missouri : 1794-1796, text compiled and annotated by Fernand Grenier and Nilma Saint-Gelais, Sillery, Septentrion, 2006, 245 p.

Vaugeois, Denis, America 1803-1853 : l'expédition de Lewis et Clark et la naissance d'une nouvelle puissance, Sillery, Septentrion, 2002, 263 p.

Villerbu, Tangi, La Conquête de l'Ouest. Le récit français de la nation américaine au 19e siècle, Rennes, Presses universitaires de Rennes, 2007, 306 p.