Maurice Richard, the Legendary Figure (part 2)

par Melançon, Benoît

Maurice Richard (1921-2000), the hockey player, was much more than just another run-of-the-mill athlete. Nicknamed ‘The Rocket', the celebrated Number 9 of the Montreal Canadiens, has been written up in all kinds of media: magazine articles and scholarly texts, biographies and souvenir collections, short stories and folk-tales, novels and children's literature, poems and plays. Songs, comic books, sculptures, paintings, films, and television shows have also been dedicated to him. His portrait has appeared on articles of clothing and toys, as well as in all sorts of advertising. Public places have been named in his honour, for without a doubt, Maurice Richard is a Quebec legend.

Article disponible en français : Maurice Richard, 2e partie: le mythe

Historians, sociologists, and specialists in literary studies have often asked whether Quebec has its own legends and legendary figures. They have proposed many candidates, including poets Octave Crémazie, Émile Nelligan, Saint-Denys Garneau, and Claude Gauvreau; essayists Arthur Buies, Edmond de Nevers, Édouard Montpetit, and Lionel Groulx; journalist Jean-Charles Harvey; strongman Louis Cyr; race car driver Gilles Villeneuve; politician René Lévesque; and many more. Yet none of these figures has ever had as much symbolic magnitude as Maurice Richard.

Maurice Richard was born in 1921 and played right wing for the Montreal Canadiens from 1942 to 1960. His career was marked by a good many athletic feats; for example, in 1944-45, he became the first player in National Hockey League history to score 50 goals in a 50-game season. Before retiring at the end of the 1959-60 season, Richard racked up one exploit after another. His statistics tell the story: 1,111 games played; 1,473 penalty minutes; 1,091 points (including 626 goals); 18 seasons; 14 times selected to the league's first or second all-star team; a member of 8 Stanley Cup championship teams; and the Most Valuable Player of 1946-47.

An Omnipresent Public Figure

Richard does not belong to the world of sports alone, for he has left his mark on Quebec society and culture and continues to make his presence felt today. This is why it is possible to describe him in terms of a legendary figure. The history of how he came to be portrayed as such can be divided into four key phases.

The first accounts concerning Maurice Richard, which come from the 1940s and 1950s, are characterized by two seemingly contradictory trends. On the one hand, his admirers felt very close to him, in that Richard was not that different from themselves: he wasn't a seven-foot-tall basketball player; he didn't run the 100-metre-dash in under 10 seconds; and he wasn't given to making great speeches. He was just an ordinary fellow, much like a friend or a relative. On the other hand-if the stories about him are to be believed-he was an entirely different person once a game began; for he wasn't just another player-he was in a league of his own! He was consumed by the desire to lead his team to victory, by an obsession with scoring goals, by unwavering determination. You could see it in his eyes. In those moments, he embodied success for a people much in need of role models-at least that was what everyone at the time kept saying.

During the 1960s, Richard's star declined somewhat. He had been a model of French-Canadian success for over 15 years in an area of the public arena typically perceived as English-Canadian dominated. But then, his style and way of being seemed to go out of synch-historically speaking-with what was happening in Quebec, or even throughout the Western world. The Rocket was a man of few words and so he felt out of place in the articulate discursive effervescence and general cultural ferment of a decade marked by a universal desire for self-expression. He was a devout Catholic, a family man, whose way of life did not fit in with the new modes of being: the revolutionary transformation of male-to-female and parent-to-child relationships; the loss of religious foundations; and the radical restructuring of values. After his hockey career ended, Richard became a businessman and represented the archetypal traditionalist in an era when rebellion was the order of the day. During the 1960s, the Rocket temporarily left the spotlight.

At the beginning of the 1970s, he once again became the topic of an astonishing variety of discussions popular among Quebec French-speakers. He was material for novelists and storytellers (Roch Carrier and Jacques Poulin), singers (Pierre Létourneau), playwrights (Jean-Claude Germain), filmmakers (Gilles Gason and Pierre L'Amare), comic-strip artists (Arsène and Girerd), as well as biographers (Jean-Marie Pellerin). Social scientists became interested more and more in what he had represented and continued to represent. The main preoccupation was as to why such a shift in the perception of Maurice Richard had occurred, long after his athletic career had ended. During the 1970s, Maurice Richard became a national celebrity. He would henceforth be much more than a simple symbol of success in the specialized field of professional sports. He had come to be considered the ideal spokesman for all those who no longer simply considered themselves to just be French-Canadians, but rather specimens of a new breed altogether: the Québécois. This transformation occurred at the very moment a new form of nationalism was emerging in Quebec-a cause that would be taken up and rapidly come to be embodied by the Parti Québécois. These neo-nationalists were searching for precursors and models-and Maurice Richard fit the bill.

In the end, the significance of Maurice Richard-whether on a political, cultural or social level-was never again challenged after the 1970s. Several statues of him were unveiled in Montreal and in Ottawa. He was also the subject of paintings (Louis Hébert, Serge LeMoyne, and Jean-Paul Riopelle) and the topic of films and television broadcasts (Charles Binamé, Jean-Claude Lord and Pauline Payette; Karl Parent and Claude Sauvé; and Luc Cyr and Carl Leblanc). Popular singer Félix Leclerc even dedicated a text to Richard and poet Bernard Pozier composed several poems about him. Maurice Richard's name still appears in advertising today (2008), nearly a decade after his death.

The fourth phase of the legend-making process began with the passing of the Rocket on the 27th of May 2000. On that day and for a number of days thereafter, the name Maurice Richard was on everybody's lips. Then, on May 30th, the Molson Centre was turned into a mortuary chapel where he was laid in state. It is estimated that over 115,000 faithful fans and devotees filed past the hockey legend's open casket. The next day, Richard was honoured with a national funeral in Montreal's Notre Dame Basilica. The media analyzed his life and career from every possible angle. His admirers left innumerable [written] testimonials in front of his home in Montreal, at the foot of his statue in front of the local arena bearing his name, at the old Montreal Forum where he played his entire career and under a marquee near the Molson Centre. The general opinion was unanimous: Maurice Richard had brought people together.

A Quebec Legend

And so, just why is it possible to describe Maurice Richard as a legendary public figure? If the many accounts of his exploits are to be believed, they were decidedly impressive. Did the opposing players try to bring him down alone or in numbers? Nothing the opposing team could do could stop him from bearing down on their goalie and hitting the puck into the net behind him (February 3rd, 1945). Did the Toronto Maple Leafs, the Montreal Canadian's archenemy and rival team need to be defeated? Richard went and scored five goals and was named the game's first, second, and third star (March 3rd, 1944). And wasn't he totally exhausted after just moving into his new home? He merely proceeded to score five goals and pick up three assists (December 28th, 1944). Wasn't he knocked senseless by an opponent? Nevertheless, he resumed the game, not knowing where he was, and drawn to the net by instinct, he managed to score the winning goal (April 8th, 1952). Did the game go into overtime and need resolution? He would, if needs be, score the winning goal, as he did in several games (March 27th - 29th, 1951, and April 16th, 1953). The cult followers of the legends of Maurice Richard still continue to sing the praises of his exploits on the ice, for without a doubt, Maurice Richard is one of the greats-if not the greatest of them all!

From 1942 up until the early 21st century (except for a brief reprieve during the 1960s) Maurice Richard remained squarely in the spotlight. Other athletes have profoundly marked the imagination of the people of Quebec, but none other has done so in such an enduring manner. One particularly significant event during Richard's 60-year reign of fame deserves special attention. It is the event that would thereafter be referred to as the "Richard Riot." On March 13th, 1955, in Boston (MA), Maurice Richard fought with Hal Laycoe of the Boston Bruins and assaulted one of the linesmen. On March 16th, the president of the National Hockey League (NHL), Clarence Campbell, suspended the Rocket for the three remaining games of the regular season and for the entire playoffs. On March 17th, fans enraged by the decision and sparked by Richard's suspension, caused a riot to break out in the vicinity of the Montreal Forum. Cars were overturned; streetcars were brought to a standstill; fires were set in roadways; windows were broken; phone booths and newspaper stands were vandalized; businesses were looted; police officers and civilians were wounded (although not seriously); and demonstrators were arrested. On March 18th, Richard addressed his fans with an appeal for a restoration of order. Of course it is a necessity that such a legendary figure have staying power, but one also needs a defining moment when all the facets of the legend converge. For Richard, that moment was the spring of 1955.

Before, during, and after the riot, did Maurice Richard truly represent all French-Canadians and, by extension, all Québécois? Was he only defending his own interests or did he defend the collective concerns of the community at large? The answers are clearly yes on both accounts. It is impossible to put just what Richard personified on a national scale into a few simple words. Nevertheless, everyone associates the Rocket with community. The Quebec population's conception of Richard's private and public image cannot be dissociated from the very evolution of the Rocket legend.

For a legend is based on real, tangible exploits. Socially speaking, it has a collective dimension and unfolds in a conscious space void of time. Furthermore, it is necessary that it be transmitted from generation to generation. The legacy of Maurice Richard has taken on two different forms. The intangible or ‘cultural' aspect of the legend is the topic of novels, stories, poetry, theatre, children's literature, biographies, memoirs and autobiographies, text-books, eulogies, paintings, drawings, sculptures, songs, television programs, films, comic strips, magazines and newspapers, radio broadcasts, on-line articles, illustrated albums, and scholarly treatises-particularly those written by historians. However, the tangible or ‘material' aspect of the Richard legend has been embodied in household products (soup, oatmeal, bread, breakfast cereals, beverages, heating oil, wine, etc.), television and printed advertising, toys and games, clothing, hockey cards, autographs, national symbols (bank notes, stamps, etc.) and all sorts of highly coveted collector's items-all bearing an endorsement or an image of Maurice Richard. These two aspects of Richard's legacy have been assembled in a pair of exhibits: the first is at the Maurice Richard Museum located in the arena that is named after him; and more importantly, the second is a part of the Canadian Museum of Civilization's travelling exhibit (Une légende, un heritage; "Rocket Richard" the Legend - the Legacy), which opened in 2004. The legend of Maurice Richard has endured because, at all levels of society and in all spheres of culture-from the most official to the most marginal-all have eagerly appropriated his image and persona.

Thus, legend is a form of discourse that harbours contradictions. It is not a discourse about absolute truth, but rather one of multiple truths. The accounts concerning Maurice Richard are numerous and sometimes contradictory. Gilles Gascon's film Peut-être Maurice Richard [It Might be about Maurice Richard] (National Film Board of Canada, 1971) presents a few of these contradictory accounts. When it comes to some of Richard's exploits, all truths have equal claim, because each individual has his or her own version, which may contradict that of his neighbour-yet remain compatible with it. For legend is composed of personal accounts that simply have to be believed.

Consequently, although it is possible to affirm and establish with certainty that Maurice Richard is a legendary figure, such an assertion requires an added nuance at one particular level. With which community should the legend of Maurice Richard be associated? While it is true that Richard has represented, and continues to represent, the French-Canadian/ Québécois community, it should not be forgotten that he is also a cult figure for English-speaking Canada as well. English-Canadian novelists, such as Clark Blaise, Mordecai Richler, and Scott Young; poets, including Roger Bell, Marty Gervais, and Al Purdy; singers such as Robert G. Anstey; playwrights including Kenneth Brown and Rick Salutin; and film-makers such as Sheldon Cohen, Brian McKenna and Tom Radford all have waxed eloquent on the virtues of the famous Number 9. Of course their perceptions of their hero, the Rocket, are not exactly the same as those of the French-speaking community, for-to each community, its own heritage!

Benoît Melançon

Professor

Département des littératures de langue française

University of Montréal

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Carrier, Roch, Le Rocket, Montréal, Stanké, 2000, 271 p.

Daoust, Paul, Maurice Richard. Le mythe québécois aux 626 rondelles, Paroisse Notre-Dame-des-Neiges, Éditions Trois-Pistoles, 2006, 301 p. Ill.

De Repentigny, Alain, Maurice Richard, Montréal, Éditions La Presse, coll. «Passions», 2005, 126 p. Ill. Avant-propos d'André Provencher. Préface de Stéphane Laporte.

Foisy, Michel et Maurice Richard fils, Maurice Richard. Paroles d'un peuple, Montréal, Octave éditions, 2008, 159 p. Ill.

Goyens, Chrystian et Frank Orr, avec Jean-Luc Duguay, Maurice Richard. Héros malgré lui, Toronto et Montréal, Team Power Publishing Inc., 2000, 160 p. Ill. Préfaces d'Henri Richard et de Pierre Boivin.

Lamarche, Jacques, Maurice Richard. Album souvenir, Montréal, Guérin, 2000, 133 p. Ill.

Melançon, Benoît, Les Yeux de Maurice Richard. Une histoire culturelle, Montréal, Fides, 2008 (nouvelle édition revue et augmentée), 312 p. Ill. URL: <http://www.lesyeuxdemauricerichard.com/>.

Pellerin, Jean-Marie, Maurice Richard. L'idole d'un peuple, Montréal, Éditions Trustar, 1998 (nouvelle édition revue et augmentée), 570 p. Ill.

Posen, I. Sheldon, 626 par 9. Une énumération chronologique des buts marqués par Maurice «Rocket» Richard en photos, statistiques et récits, Gatineau, Musée canadien des civilisations, 2004, 34 p. Ill. Traduction de Marie-Anne Délye-Payette. Révision de Jean-Luc Duguay. Avant-propos de Roch Carrier.

Additional DocumentsSome documents require an additional plugin to be consulted

Images

-

Arena Maurice Richard

Arena Maurice Richard

-

Aréna Maurice Richard

Aréna Maurice Richard

-

Banquet de clôture de

Banquet de clôture de

la convention ... -

Exposition agricole d

Exposition agricole d

e Sherbrooke, a...

-

Exposition agricole d

Exposition agricole d

e Sherbrooke, a... -

Exposition agricole d

Exposition agricole d

e Sherbrooke, a... -

Maurice Richard

Maurice Richard

-

McAvity M59M Hydrant

McAvity M59M Hydrant

-

Monument, Arena Mauri

Monument, Arena Mauri

ce Richard -

Old Montreal Forum si

Old Montreal Forum si

te -

Place du Centenaire -

Place du Centenaire -

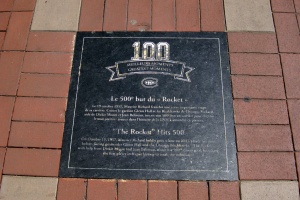

100 Meilleurs ... -

Place du Centenaire -

Place du Centenaire -

Maurice Richar...

-

Place du Centenaire -

Place du Centenaire -

Pièce du Cente... -

Richard Soup

Richard Soup

-

Salon de l'agricultur

Salon de l'agricultur

e de Montréal, ... -

Statue de Maurice Ric

Statue de Maurice Ric

hard à Gatineau...

Vidéo

Documents PDF

-

Émeute au Forum: qui sème le vent...

Émeute au Forum: qui sème le vent...

-

L'émeute au Forum, première révélation du mythe Richard

L'émeute au Forum, première révélation du mythe Richard

-

Le devoir de philo - Maurice Richard, héros stoïcien

Le devoir de philo - Maurice Richard, héros stoïcien

Hyperliens

- Online Exhibition: « Rocket » Richard,Canadian Museum of Civilization

- Reportage photo, Radio-Canada: Maurice « Rocket » Richard (1921 - 2000) [French only]

![Allo [Hello] Maurice](/media/thumbs/2400/300x200-maurice_richard_statue_gatineau.jpg)