Recent Articles

The Point: a Franco-American Heritage Site in Salem, Massachusetts

Traditional French Songs in Ontario

Fort William, Crossroad of a Fur Trading Empire

The Guigues Elementary School in Ottawa

Centre franco-ontarien de folklore (CFOF)

Centre de recherche en civilisation canadienne-française (CRCCF)

Articles

-

A Quick History of French-Speakers in Louisiana (1682–1900)

Louisiana, a land of cultural mixing, was officially proclaimed a French territory and named in honour of King Louis XIV by explorer Cavelier de Lasalle in 1682. The territory subsequently changed hands several times—ceded to Spain in the Treaty of Paris in 1763, recovered by France in 1800, then, three years later, sold by Napoleon to the United States—but these shifts of allegiance did not lead to the disappearance of French in the area. They did, however, produce a specific cultural mélange due to successive migrations of Acadians, Creoles, American Indians, Spaniards and Europeans of diverse origins. Up until the early 20th century, francophone language and culture remained predominant. In this article, videographer Helgi Piccinin explores the characteristic mix of cultural influence and colours that continues to survive in francophone Louisiana.

-

Acadian Aboiteaux [Dike and Suice Gate System]

The word aboiteau [dike and sluice system] has become a central part of the identity of the Acadian people, the maritime technology being so closely linked with the rise and evolution of this group of people during the 17thand 18th centuries. Even after the Deportation of the Acadian people in the 1750s, this farming practice was preserved in some of the Acadian regions.The aboiteau-style dike and sluice has now become a symbolic part of the cultural heritage of the Acadian community, which still perpetuates the memory of the maritime technology's historic importance. Throughout the colonial period, Acadians were the only people in North America to cultivate below sea level farmlands to such a large extent. These exceptionally fertile lands were the key to the community's prosperity up until the even of the Deportation in 1755. Moreover, these large-scale earthworks were community projects. This sets them apart from similar projects undertaken elsewhere in the world. The communal tasks necessary to building and maintaining the large network of dikes have helped forge the Acadian identity into what it is today.

-

Baron of Lahontan

After having enjoyed a considerable success in Europe with the 1702-1703 publication of his three-volume memoire - mainly inspired from his long stay in New France (1686-1693) - Lahontan was all but forgotten for more than two centuries. Then his works were rediscovered in the 1970s, and subsequently came to be considered essential, as they offered a better understanding of the literary evolution of the travel literature genre, as well as of the libertarian movement that swept over Europe during the age of Enlightenment of the 18thcentury. His work is also thought to be an invaluable contribution to the history of New France. Lahontan, an antihero who was not nearly as publicised as Champlain or other legendary characters of New France, has produced a work that today still assists scholars in better understanding French cultural heritage and history.

-

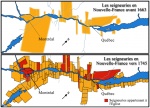

Beauport «Seigneurie»

Few concepts are as closely linked with the history of Quebec as the seigneurial [feudal] system, which was established along the St. Lawrence River in the early days of colonisation by the French. The landscape, heritage assets and place names of the St. Lawrence valley still bear the marks of seigneurial feudalism, which, after having survived for nearly a hundred years under British rule, was abolished in 1854. However, Quebec-especially rural Quebec-continued to be defined by the seigneurial system long after 1854. Although seigneuries were a major cornerstone of Quebec's history, the remaining traces of their existence do not always reflect their importance. In some areas, the remains of a seigneurie have given rise to a veritable heritage industry, while in others they seem to have faded into obscurity. Beauport, one of the oldest seigneuries in Canada, is a perfect example of this paradox.

-

Catherine de Saint-Augustin, Remembered from Quebec to Normandy

Beatified by Pope Jean-Paul II in 1989, Catherine de Saint-Augustin is considered to be one of the founders of the Canadian Roman Catholic church. Born in Saint-Sauveur-le-Vicomte (Normandy, France) in 1632, Catherine de Longpré joined the ranks of the hospital order in Bayeux in 1644. A short time later she volunteered to assist the nuns operating the Quebec City Hôtel-Dieu hospital, and so, in 1648, she set foot in New France for the first time. In the land of her adoption, she led an exemplary life and died there of an illness at a very young age in 1668. Her growing renown in the Province of Quebec in the 19th century for her good works eventually opened the way for her to be venerated in her homeland of France.

-

Étienne Brûlé, The First Franco-Ontarian

Étienne Brulé, despite being an occasional sidekick to Samuel de Champlain, is an obscure character in the history of New France. He left no writings and we know very little about his life. The accounts of life, as few as they may be, have nonetheless have undergone many changes in the last 400 years. Sometimes presented as a traitor and at other times a hero, people are fascinated by his scandals, his achievements, and the mystery surrounding his death. Today, he is celebrated as the first French settler to have lived in the territory that is now the province of Ontario. Some view him as the founder of the French-speaking community in Ontario.

-

Father Potier’s Glossary of Spoken Canadian French

The French language is without a doubt the key heritage element shared by New World French speakers. Over a period of four centuries, North American French has survived and evolved, its various dialects and accents multiplying as a result of the diverse natural and cultural surroundings in which it has taken root. Furthermore, the various cultural encounters and conflicts, as well as the occupations, vocations, and areas of expertise of its speakers have their mark on the vocabulary, the expressions and the structure of each variety of the language. One of the most important documents for the study of the history of North American French is the manuscript entitled Façons de Parler Proverbiales, Triviales, Figurées, etc., des Canadiens au XVIIIe Siècle [Proverbial, Everyday and Figurative Expressions, etc. of 18th Century Canadians]. It is a little notebook compiled between 1743 and 1758 by Father Pierre Philippe Potier, a Jesuit missionary to the Hurons of the Detroit River region. This glossary of spoken Canadian French was the first - and in fact the only - work of its kind to document the French spoken in New France. Potier jotted down most of the words of his glossary while serving in the Detroit River area, where he was a missionary from 1744 until his death in 1781. The document is therefore of great importance to the French speakers of this region.

-

French in Newfoundland

Today, French-speakers represent only a small fraction of Newfoundland and Labrador's population. Although, since the 16th century, the French have left many traces of passing in the history of this territory, their presence today more resembles the stuff of imagination rather than anything concrete or deeply rooted. This anthropological reality is somewhat like a "phantom" cultural community which is fed by numerous memories, cultural echoes that have been passed on by history and literature, as well as by the names of places and a few traces of a past that have almost vanished. Yet, the region's French past is well acknowledged, studied and even commemorated. The 2004 celebrations were such an occasion to renew the French cultural heritage of Newfoundland and Labrador.

-

La Rochelle and French North America

La Rochelle’s history is the history of its various ports, which manifest La Rochellers’ ability to embrace the changing dynamics of the Atlantic seaway in the 12th through the 18th centuries. La Rochelle’s early involvement in the great discoveries and its commerce with the Americas and the rest of the world—determined by the whims of colonial shipping companies and economic opportunities—established this port town as one of the major seaboard towns of the Atlantic realm. La Rochelle’s story goes way back! It is not surprising to find, in La Rochelle and the surrounding territory (greater La Rochelle today boasts a population of nearly 150,000) and in the urban landscape of the old town, the traces of the French adventure in North America—an adventure of Franco-Quebecois cooperation that continues to this day in many forms.

-

Marie de l’Incarnation Memorial Sites in Tours

Marie Guyard, better known as Marie de l’Incarnation, was born in Tours, France. She lived there forty years, from birth in 1599 until she left for Canada in 1639. She is one of the pioneers of New France, where she founded the Ursuline convent at Quebec City, the first school for Indian and French girls in North America. She lived in this convent until her death in 1672. While she is well known in Quebec, her memory was almost forgotten in her native land, where only a handful of devotees, scholars and city councillors remembered this modest provincial woman of the seventeenth century, who left for Canada’s “few acres of snow”. However, since the 1950s, thanks to the tireless efforts of a group made up of Canadians and Tourangeaux, supported by a few elected officials aware of the influence of the French language in North America, the memory of Marie Guyard is finally receiving the attention it deserves in Tours.

-

Musée du Nouveau Monde, La Rochelle, France

Housed in a magnificent 18th century private residence, Musée du Nouveau Monde’s collections tell the story of France’s relations with the Americas as conducted from La Rochelle, one of the main ports of New World trade and migration. Paintings, engravings, old maps, sculptures, furniture and decorative art objects conjure up images of Canada, the West Indies, and Brazil as well, with records of the transatlantic slave trade. A section is also devoted to the indigenous peoples of North America and the Far West.

-

Old Quebec, a UNESCO World Heritage site

Old Quebec, a historic district of Quebec City, was inscribed on UNESCO’s World Heritage List in 1985. At that time it was characterized as “the cradle of the French civilization in America”, a “fortified city” and “always animated”. As the administrative centre of New France, governing a territory that spanned almost a third of North America, the city of Quebec served as headquarters for civil, judicial and religious governance under the French regime. Despite attacks, battles, regime changes and the ups and downs of economic life, Quebec City has maintained its role as capital, preserved its vitality or restored it during more difficult times, and protected and developed its heritage. Because the people living and working there consider its heritage to be their own, Old Quebec is an excellent example of a living urban heritage environment that continues to evolve.

-

Quebec Beer, Brewers and Breweries

Beer is the most popular alcoholic beverage in Canada and Quebec. Beer drinking as a tradition dates back to the days of New France, making brewing one of the oldest trades practiced in the Lawrence Valley. However, both brewing practices and the popularity of beer underwent significant changes, as the British tradition began to have a strong influence on the beer industry through the establishment of the first large-scale modern-day brewery, the Molson Brewing Company. The Industrial Revolution made it possible for beer to become a mass-produced commodity, brewed and bottled in factories and distributed by increasingly sophisticated infrastructures. Nowadays, microbreweries have revived the practices of artisanal brewing, as a number of festivals celebrate the many varieties of this ancient beverage.

-

St. Lawrence Beluga

Since the 1980s, both individuals and communities of researchers have raised their voices in a cry of alarm, calling out for the protection of the St. Lawrence beluga. During this period, this loveable little white whale has become a global symbol of endangered wildlife. Today the beluga is the focus of numerous scientific studies, and although several measures have been put in place to protect it, the species is still in danger of extinction. This, however, has not always been the case. In 1920, for example, a bloody struggle was undertaken to reduce the number of belugas, because at that time, they were considered to be the enemy of the fishing industry. The whales were thought to devour large quantities of cod and salmon and other kinds of fish of commercial value. And so the role of the beluga in the life of the communities established along the St. Lawrence River has changed considerably over time, and what was once a natural resource to be exploited has become a heritage to be preserved.

-

The Chemin du Roy between Quebec City and Montreal

Today the Chemin du Roy, or King’s Highway, is a well known heritage route. Motorists along the north bank of the St. Lawrence River between Quebec City and Montreal can take Highway 138, which follows the approximate path of the original King’s Highway. Along the Chemin du Roy tourist route, blue signs guide drivers from town to village among the region’s heritage buildings and landscapes. Avenue Royale—which is a continuation of the original Chemin du Roy east of Quebec City—is yet a further occasion to visit and take in several additional heritage treasures. But the original King’s Highway, which was the first road to link Quebec City with Montreal was built in 1734. Along its winding course one can discover a condensed history of transportation in the St. Lawrence Valley.

-

True Portrait of Marguerite Bourgeoys

The post-mortem portrait of Marguerite Bourgeoys is the only surviving contemporary depiction of one of the most remarkable figures in the history of Montreal during the 17th century. Painted in 1700 by Pierre Le Ber, the work has been in the hands of the Congregation of Notre-Dame ever since and is currently exhibited at the Marguerite Bourgeoys Museum. During the 19th and early 20th centuries, the portrait was retouched several times, completely altering its appearance. The restoration of the painting in 1963-1964 revealed the true face of Marguerite Bourgeoys and the authentic work of one of Canada's earliest painters.

Images

-

Carte géographique de

la Nouvelle-Fr...Article :

Champlain’s astrolabe: the journey of a mythical Canadian heritage object -

Monument de l'histori

en Guy Frégault... -

Mort héroïque de quel

ques pères de l...Article :

Royal College La Flèche, Wellspring of Missionary Zeal -

Arrivée de l'Aigle d'

Or au Bassin Lo...

-

Défilé des bénévoles

incarnant les F... -

Défilé des bénévoles

incarnant les F... -

Foule assistant à l'a

rrivée des béné... -

L'arrivée de l'Aigle

d'Or transporta...

-

La ministre du gouver

nement du Québe... -

Les bénévoles incarna

nt les Filles d... -

Les bénévoles personn

ifiant les Fill... -

Les Filles du roi se

préparent à déb...

-

Plaque en hommage aux

Filles du roi ... -

Dessin du fort de Cha

rtres tel qu'il...Article :

Fort de Chartres in Illinois -

Les compagnons de Nou

velle-France -

Les compagnons de Nou

velle-France

-

Carte des fondateurs

de la Nouvelle-... -

Copie d'un tableau ré

puté authentiqu... -

Paul Le Jeune, missio

nnaire jésuite ... -

8 mai 2008, le navire

le Bélem passe...Article :

La Rochelle and French North America

-

Affiche de l'événemen

t «En route pou...Article :

La Rochelle and French North America -

Affiche de l'expositi

on permanente «...Article :

La Rochelle and French North America -

Cartes sur la provena

nce des migrant...Article :

La Rochelle and French North America -

Façade de la chapelle

de l'hôpital S...Article :

La Rochelle and French North America

-

Plan de La Rochelle e

n 1685 (copie d...Article :

La Rochelle and French North America -

Première page d'une l

ettre expédiée ...Article :

La Rochelle and French North America -

Vitrail de l'église N

otre-Dame de Mo...Article :

La Rochelle and French North America -

Détail d'une carte de

la Nouvelle-Fr...

-

Requête présentée au

grand voyer de ... -

Eglise paroissiale Sa

int-Rémi, 2004 -

Musée de Falaise, 200

2 -

Musée des huit maison

s à Archigny, F...

-

Plaque commémorative

d'Antoine Bourg... -

Plaque commémorative

de la famille ... -

Plaque commémorative

de la ferme aca... -

Plaque commémorative

du départ vers ...

-

Stèle commémorative d

e Nicolas Denys... -

Vue rapprochée de la

plaque figurant... -

Bibles, psautiers et

livres protesta... -

Bibles, psautiers et

livres protesta...

-

Arrivée des Ursuline

s et des Hospit... -

Marie de l'Incarnatio

n enseignant à ... -

Prermière résidence d

es ursulines de... -

Exposition permanente

Vie bourgeoise...

-

Marguerite Bourgeoys

enseignant la c...Article :

Marguerite Bourgeoys Museum and Notre-Dame-de-Bon-Secours Chapel -

Bulletin de la Sociét

é historique et... -

Carte de l'Amérique

septentrionale ...Article :

Place-Royale: Where Quebec City Began Quebec’s Place-Royale, the Reflection of a City -

Fêtes de la Nouvelle

-France à Place...Article :

Place-Royale: Where Quebec City Began Quebec’s Place-Royale, the Reflection of a City

-

Cartes sur l'organisa

tion des seigne... -

La présence des Sulpi

ciens sur l'île...Article :

Saint Sulpice Seminary, Montreal -

Carte de la Nouvelle-

France, 1657Article :

Sainte-Marie-among-the-Hurons: a little-known gem of “Ontario’s New France”

Vidéos

-

Lieu historique du Fort-Témiscamingue-Obadjiwan

Ce film présente le lieu historique du Fort-Témiscamingue-Obadjiwan, fondé pour le commerce des fourrures à l’époque de la Nouvelle-France et maintenu par les Anglais après 1760. Ce site d’interprétation historique retrace les grandes étapes du Fort-Témiscamingue au sein desquelles les Anglais, les Français et les Amérindiens ont collaboré à la traite. On reconstitue aussi diverses activités reliées à la traite des fourrures, telles que la construction de canots d’écorce. * Durée: 1min29.

Article :

Fort Témiscamingue on Obadjiwan Point: a Place for Meeting and Exchange

Documents sonores

Documents PDF

-

Beaubassin, vestiges de l’Acadie historique

Géopolitique de Beaubassin à l'époque de la Nouvelle-France. Taille: 66 Ko.

-

Lettre que Mgr de Laval écrivait au Général des Jésuites à Rome quelques semaines après son arrivée en Nouvelle-France, en 1659

Taille: 46 Kb

Article :

Royal College La Flèche, Wellspring of Missionary Zeal -

Analyses du portrait de Marguerite Bourgeoys

Ce document présente deux analyses du véritable portrait de Marguerite Bourgeoys tel que peint par Pierre Le Ber à l'époque de la Nouvelle-France. Taille: 3Mb

Article :

True Portrait of Marguerite Bourgeoys