Recent Articles

The Point: a Franco-American Heritage Site in Salem, Massachusetts

Traditional French Songs in Ontario

Fort William, Crossroad of a Fur Trading Empire

The Guigues Elementary School in Ottawa

Centre franco-ontarien de folklore (CFOF)

Centre de recherche en civilisation canadienne-française (CRCCF)

Articles

-

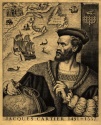

Jacques Cartier

Jacques Cartier was among a group of explorers who left Spain, Portugal, England and France in the 16th and 17th centuries, mainly in search of a passage towards the elusive and mythical China. Cartier became one of the "discoverers" of the New World, an immense pair of continents now called the Americas, which blocked the path of all the navigators to the Far East. He was a meticulous explorer who mapped out a vast territory extending from the Gulf of St. Lawrence to the village of Hochelaga (present-day Montreal), all of which he claimed for the King of France. Cartier did not however manage to found a permanent colony. During the 19th century, the first historians of French Canada proclaimed Jacques Cartier the discoverer of Canada, for the idea of a French discoverer served the emerging nationalist interests very well indeed.

-

Arthur-Villeneuve House: a Testimony to an Artist’s Life and Work

Visitors to the Musée de la Pulperie de Saguenay are undoubtedly surprised to see painter Arthur Villeneuve's home displayed inside the museum like some piece of artwork. The residence, originally a museum within a house, is filled with pieces by local barber and painter Arthur Villeneuve. The residence-cum-museum was the object of many heated discussions before being established as a remarkable artistic statement. Considered naïve art, or perhaps art in its most basic form, Villeneuve's pieces may at first glance seem traditional or picturesque in origin, but they sometimes reveal a hint of surrealism. The artist's home, recognised as a national heritage asset by the Canadian government in 1993, has since come to hold a special place in the history of 20th centuryQuebec art.

-

Assomption Sash

The Assomption (or arrow) sash is a symbolic piece of clothing central to the culture of the French-speaking population of North America. The item was widely worn for almost a century, from the end of the 18th to the end of the 19th century, before it fell into disuse, a result of the decline of the fur trade industry. Subsequently, this "masterpiece of Canadian domestic textile industry", as E.-Z. Massicotte once put it, came to be associated with the traditional cultures of the French-Canadian and the Métis. Today, enthusiasts have committed themselves to safeguarding of this cultural custom. Thanks to artisans who continue to weave sashes according to traditional methods, this unique technique has been kept alive.

-

Cirque du Soleil (Origins): Les Échassiers de la Baie and the Baie-Saint-Paul Fête Foraine [Festival]

To date (2009), the Cirque du Soleil is without a doubt Quebec's most internationally renowned cultural enterprise. This undeniable commercial success is the fruit of projects that took place in Baie-Saint-Paul (in the Charlevoix region) in the 1980s. At the time society was ripe for such an experimental endeavour, particularly because during the 1970s in Quebec, a substantial part of the rising generation left urban population centres in search of a different worldwith different values. As a result, many "rediscovered" Charlevoix and Baie-Saint-Paul and since, the region has become a mecca for many hippies and migrant peoples. It was truly of a case of somewhere between "the Gaspé and all the way to California," to cite Pierre Flynn. 25 years after its humble beginnings in Charlevoix, this monumental cultural enterprise today known as the Cirque du Soleil has finally taken its rightful place in the history of the community of Baie-Saint-Paul and now it constitutes an important piece of cultural heritage for Quebec.

-

Community Governance of the Francophone Minority: a Cultural Heritage

As a whole, the francophone minority in Canada has survived and is developing thanks to a constant investment in what could be called community governance, that is, the forms of organization that it has adopted in order to form a group and to influence public authorities. Governance of the francophone minority, now woven throughout the fabric of the country, was formed gradually to protect against the attacks of an often-hostile majority. By its persistence and its resilience, this governance is rich in lessons learned and is an integral part of French cultural heritage in North America.

-

Dollard des Ormeaux

Adam Dollard des Ormeaux, an emblematic figure representative the history of New France, was long the object of extraordinary patriotic fervor. The battle that he waged with a handful of comrades against an entire Iroquois army in 1660 left its mark on the collective memory. The festivities in honour of his "Long Sault exploit" reached its peak during the 1920-70 period and was celebrated in many ways, most notably the Fête de Dollard celebrated every year in Quebec on the same date as Victoria Day in the rest of Canada. Nevertheless, since 2003, this celebration has been replaced by National Patriots' Day, a clear indication that this figure and his heroic feats no longer have the same widespread significance. One day, the question may arise as to what extent Dollard des Ormeaux is still part of French cultural heritage in North America.

-

French Culture in North America; Chateaubriand’s Travels and Literature

Chateaubriand's voyage that took him to the United States and along the Canadian border in 1791 was one of discovery that left its mark on his life's work. His ode to the New World sung in his novels and travel books have made him, in the eyes of generations of 19th century romantics, the "inventor of America" and, more precisely, the one who reinvented Louisiana. In retelling and glorifying the experiences of explorers, missionaries, travellers, and naturalists from the early days of New France to his own times, his works gave numerous generations of Europeans a yearning for the Americas. And so, for these reasons, Chateaubriand should be considered an integral part of French cultural heritage in North America.

-

French in Newfoundland

Today, French-speakers represent only a small fraction of Newfoundland and Labrador's population. Although, since the 16th century, the French have left many traces of passing in the history of this territory, their presence today more resembles the stuff of imagination rather than anything concrete or deeply rooted. This anthropological reality is somewhat like a "phantom" cultural community which is fed by numerous memories, cultural echoes that have been passed on by history and literature, as well as by the names of places and a few traces of a past that have almost vanished. Yet, the region's French past is well acknowledged, studied and even commemorated. The 2004 celebrations were such an occasion to renew the French cultural heritage of Newfoundland and Labrador.

-

La Rochelle and French North America

La Rochelle’s history is the history of its various ports, which manifest La Rochellers’ ability to embrace the changing dynamics of the Atlantic seaway in the 12th through the 18th centuries. La Rochelle’s early involvement in the great discoveries and its commerce with the Americas and the rest of the world—determined by the whims of colonial shipping companies and economic opportunities—established this port town as one of the major seaboard towns of the Atlantic realm. La Rochelle’s story goes way back! It is not surprising to find, in La Rochelle and the surrounding territory (greater La Rochelle today boasts a population of nearly 150,000) and in the urban landscape of the old town, the traces of the French adventure in North America—an adventure of Franco-Quebecois cooperation that continues to this day in many forms.

-

Marie de l’Incarnation Memorial Sites in Tours

Marie Guyard, better known as Marie de l’Incarnation, was born in Tours, France. She lived there forty years, from birth in 1599 until she left for Canada in 1639. She is one of the pioneers of New France, where she founded the Ursuline convent at Quebec City, the first school for Indian and French girls in North America. She lived in this convent until her death in 1672. While she is well known in Quebec, her memory was almost forgotten in her native land, where only a handful of devotees, scholars and city councillors remembered this modest provincial woman of the seventeenth century, who left for Canada’s “few acres of snow”. However, since the 1950s, thanks to the tireless efforts of a group made up of Canadians and Tourangeaux, supported by a few elected officials aware of the influence of the French language in North America, the memory of Marie Guyard is finally receiving the attention it deserves in Tours.

-

Mount Royal Park, a Precious Natural and Cultural Heritage

Between the Laurentians and the Appalachians, the St. Lawrence Plain is punctuated by a series of hills extending from east to west. These Monteregian Hills, as they are known, were formed by intrusions of molten magma over 100 million years ago. One of them, Mount Royal, dominates the largest island of the Montreal archipelago, right in the heart of Quebec's biggest city. This remarkable urban park is subject to equally remarkable protection and enhancement measures. Exploring the mountain’s rich, multifaceted heritage is a perfect way to reconnect with the natural and human history of Montreal and appreciate the charms of its natural and human landscapes, a testimony to ongoing efforts to balance nature and culture.

-

Musée du Nouveau Monde, La Rochelle, France

Housed in a magnificent 18th century private residence, Musée du Nouveau Monde’s collections tell the story of France’s relations with the Americas as conducted from La Rochelle, one of the main ports of New World trade and migration. Paintings, engravings, old maps, sculptures, furniture and decorative art objects conjure up images of Canada, the West Indies, and Brazil as well, with records of the transatlantic slave trade. A section is also devoted to the indigenous peoples of North America and the Far West.

-

Old Quebec, a UNESCO World Heritage site

Old Quebec, a historic district of Quebec City, was inscribed on UNESCO’s World Heritage List in 1985. At that time it was characterized as “the cradle of the French civilization in America”, a “fortified city” and “always animated”. As the administrative centre of New France, governing a territory that spanned almost a third of North America, the city of Quebec served as headquarters for civil, judicial and religious governance under the French regime. Despite attacks, battles, regime changes and the ups and downs of economic life, Quebec City has maintained its role as capital, preserved its vitality or restored it during more difficult times, and protected and developed its heritage. Because the people living and working there consider its heritage to be their own, Old Quebec is an excellent example of a living urban heritage environment that continues to evolve.

-

Parc national de l’île Bonaventure et du Rocher Percé

Perched at the easternmost tip of the Gaspé Peninsula, Percé, with its unique and awe-inspiring geology, has garnered centuries of attention. With a landscap ecomposed of sheer cliffs, a giant limestone monolith, red soil and a white cape, Percé is an awe-inspiring marriage of sea and mountains that stands out as one of Quebec's natural wonders. Percé's centuries-old human history was marked first and foremost by the fishing industry and then by the tourist trade. Furthermore, the area houses two of Canada's natural heritage crown jewels: breath taking Percé Rock and Bonaventure Island, home to the world's largest colony of gannets. Parc National de l'île-Bonaventure-et-du-rocher-Percé was founded in 1985 to ensure that these exceptional natural assets would be protected for future generations.

-

Parc national du Bic

Parc national du Bic is a Quebec national park created in October 1984 to preserve and present a representative sample of the St. Lawrence Estuary’s south shore. Long renowned for its unique and spectacular scenery, the park is home to numerous animal and bird species, including white-tailed deer, red foxes and fishers. Visitors flock to see harbour seals—the park’s emblem—as well as common eider and various birds of prey. And over 744 vascular plants have been catalogued by botanists over the past 100 years, not counting moss and carex. Every year, the park welcomes more than 160,000 people who come to enjoy the breathtaking surroundings and a host of outdoor and discovery activities.

-

Plains of Abraham

Of all the places associated with French heritage in North America, the Plains of Abraham are undoubtedly among the most frequently visited and best known natural and historic sites. The battles that were fought there in 1759 and 1760 between the French and English armies have marked the collective memory as a major turning point in the history of Canada and the Western world. Over the course of the years, in accordance with ever-shifting and evolving loyalties, the site has served to convey a number of symbolic representations and has stood for many ideals. Nevertheless, the real history of the Plains of Abraham remains little known.

-

Quebec City’s Cantilever Bridge

The Pont de Québec [Bridge] has left its mark on the history of transportation and engineering in Canada. It is the world's longest cantilever bridge, with 549 metres of clear span between its main pillars; it exceeds the Firth of Forth Bridge near Edinburgh, Scotland, by 28 metres. At the beginning of the 20th century, the promoters of the Quebec Bridge project described the endeavour as the future eighth wonder of the world, particularly because its construction represented such a colossal challenge for the era. In fact, this feat of civil engineering was accomplished with great difficulty, and that, only after decades of expectation and two unsuccessful attempts that caused the death of 89 workers. The Quebec Bridge was, at last, successfully completed on September 20th, 1917, as over 125,000 spectators watched enthusiastically. Today it is considered as a world-class engineering masterpiece and has been designated as an International Historic Civil Engineering Landmark and a National Historic Site of Canada.

-

Quebec’s Flag, the Fleurdelisé

Between the end of the Troubles of 1837 and 1838 and the Second World War, French Canadians usually flew the blue, white and red tricolor flag of France, which to them best represented their distinct character. But at the turn of the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, francophones began to call for a flag of their own that would be more in accord with their North American identity. A number of designs submitted from 1901 to 1905 helped lead the way to the present flag, particularly the Fleurdelisé of Father Elphège Filiatrault and the Carillon Sacré-Cœur. Finally, on 21 January 1948 the Fleurdelisé as we know it today became the official flag of Quebec. Since then it has been a strong symbol of Quebecois identity, flying over the official buildings of Quebec and in front of many private residences, or proudly raised by the people in various circumstances, particularly at important historical moments.

-

Saint-Jean-Baptiste Society Network: from French-Canadian Unity to Quebec Nationalism

The Réseaux des Sociétés Saint-Jean-Baptiste [Network] has always been at the front lines of the various movements for claiming and affirming French Canadian identity and language rights (and more recently those of French-speaking Quebeckers) . Founded in 1854, this network, which is an offshoot of the Montreal Saint-Jean-Baptiste Association, has helped to forge the legends and symbolism associated with the shared history of French-speaking North Americans, a group that includes not only communities of Canadian origin, but also groups composed of U.S. Acadian emigrants. The Network has held a leadership role in political, cultural and social circles for over 150 years. This is why the history of the network can be considered as being synonymous with the identity discussions that have marked the past of the various French-speaking communities in North American, particularly because the Society has played a key role in the development of French-Canadian heritage.

-

Saint-Roch: Quebec City’s Urban Core is Reborn

Saint-Roch began its life as a working class quarter, the first outside Quebec City’s walls. For many years the most prosperous and populous part of the city, it was also home to much of the francophone community. From the mid 19th century to the late 1950s, Saint-Roch was Quebec City’s commercial, industrial and manufacturing centre. Today, with its rich architectural heritage and creative, resourceful population, Saint-Roch is the living legacy of four centuries of urban history, a testimony to the massive effort to save, restore, and bring new life to the city’s urban core.

-

St. Lawrence Beluga

Since the 1980s, both individuals and communities of researchers have raised their voices in a cry of alarm, calling out for the protection of the St. Lawrence beluga. During this period, this loveable little white whale has become a global symbol of endangered wildlife. Today the beluga is the focus of numerous scientific studies, and although several measures have been put in place to protect it, the species is still in danger of extinction. This, however, has not always been the case. In 1920, for example, a bloody struggle was undertaken to reduce the number of belugas, because at that time, they were considered to be the enemy of the fishing industry. The whales were thought to devour large quantities of cod and salmon and other kinds of fish of commercial value. And so the role of the beluga in the life of the communities established along the St. Lawrence River has changed considerably over time, and what was once a natural resource to be exploited has become a heritage to be preserved.

-

Tadoussac between Forest and Sea

Tadoussac, lying at the confluence of the Saguenay and Saint Lawrence rivers, possesses a rich natural and cultural heritage. Originally a site for trade between Amerindian nations, it was later frequented by Basque, Breton and Norman fishermen. Its first permanent settlements were built in the first third of the seventeenth century. Tadoussac became New France's most important port, and the main trading post of the huge Domaine du Roi. Later, with industrialization and development of the region, its economic and touristic value grew. With its magnificent countryside, natural resources and history, Tadoussac makes its mark on land and on sea, as seen by the numerous heritage events still taking place today.

-

Wayside Crosses

Nearly3,000 wayside crosses are still standing along the highways and byways of theProvince of Quebec. They representa precious heritage-a legacy of the past. The first crosses were erected by Jacques Cartier as a symbol ofterritorial appropriation. Later,the pioneers used them to mark the founding of a village and French Canadianpeasant farmers (then known as habitants) did thesame upon staking their land claims. All sorts of reasons have led French Canadians to put up waysidecrosses: farmers set them up closeto their fields for divine protection; parish priests erected them to indicatethe site of a future church; parishioners raised them up on the halfway pointalong a concession or range road, where they would gather for the eveningprayer. Although wayside crossesare first and foremost religious objects, over time they have taken on a moreheritage-oriented significance, their distinctive outline characterising aparticularity of the Quebec countryside that has come to be associated with thefaith of the French Canadian forefathers.

Images

-

Caribou sur le Mont J

acques CartierArticle :

Gaspé Caribou -

Caribou sur le Mont J

acques CartierArticle :

Gaspé Caribou -

Caribou sur le Mont J

acques CartierArticle :

Gaspé Caribou -

Jeune caribou (faon)

sur le Mont Jac...Article :

Gaspé Caribou

-

Charte de la Commande

rie Alexandre-A...Article :

Centre de recherche en civilisation canadienne-française (CRCCF) -

Charte de la Commande

rie Alexandre-A...Article :

Community Governance of the Francophone Minority: a Cultural Heritage -

Jacques Cartier prena

nt possession d...Article :

Wayside Crosses -

Le drapeau national "

Jacques Cartier...

-

Défilé historique: Ja

cques Cartier e...Article :

Jacques Cartier -

Intérieur de la maiso

n de Jacques Ca...Article :

Jacques Cartier -

Jacques Cartier

Article :

Jacques Cartier -

Jacques Cartier Bridg

e Montreal, Can...Article :

Jacques Cartier

-

Jacques Cartier dress

e une croix, Qu...Article :

Jacques Cartier -

Jacques Cartier monum

ent overlooking...Article :

Jacques Cartier -

Jacques Cartier racon

tant le récit d...Article :

Jacques Cartier -

Jacques Cartier renco

ntre les Indien...Article :

Jacques Cartier

-

Jacques Cartier sur l

e mont Royal, v...Article :

Jacques Cartier -

Jacques Cartier. phot

ographie d'une ...Article :

Jacques Cartier -

L' arrivée de Jacques

Cartier à Hoch...Article :

Jacques Cartier -

L'arrivée de Jacques

Cartier à Québe...Article :

Jacques Cartier

-

L'arrivée de Jacques

Cartier a Québe...Article :

Jacques Cartier -

L'arrivée de Jacques

Cartier à Stada...Article :

Jacques Cartier -

La signature de Jacqu

es CartierArticle :

Jacques Cartier -

Pont Jacques Cartier

Bridge, Montréa...Article :

Jacques Cartier

-

Portrait imaginaire d

e Jacques Carti...Article :

Jacques Cartier -

Québec. 1908. Jacques

Cartier & Donn...Article :

Jacques Cartier -

Saint-Malo, avril 153

4, vers 1928Article :

Jacques Cartier -

Statue de Jacques Car

tier à Montréal...Article :

Jacques Cartier

-

Tricentenaire de Québ

ec 1908. Jacque...Article :

Jacques Cartier -

Université de Montréa

l, division des...Article :

Jacques Cartier -

Jacques Cartier sur l

e mont RoyalArticle :

Mount Royal Park, a Precious Natural and Cultural Heritage -

Buste de Jacques Cart

ier

-

Intérieur de la maiso

n de Jacques Ca... -

La rue de Buhen où se

trouvait la ma... -

Le Manoir de Jacques

Cartier à Limoi... -

Le Manoir de Jacques

Cartier à Limoi...

-

Manoir de Jacques Car

tier à Limoilou... -

Sépulture de Jacques

Cartier -

Statue de Jacques Car

tier -

Statue de Jacques Car

tier

Vidéos

-

Jacques Cartier

(Film muet) Ce film présente divers monuments et évènements commémorant les découvertes et les voyages de Jacques Cartier au Canada. Sur l’avenue du Parc à Montréal, on assiste à une célébration devant le monument érigé à la mémoire de Cartier. En 1935, à North Bay, Ontario, la communauté canadienne-française érige une croix pour commémorer l’arrivée de Cartier en 1534. On voit aussi la réplique du bateau la Grande Hermine lors de l’Expo 67 à Montréal, à l’occasion d’une animation historique. On découvre aussi les stèles gravées d’images et d’écritures retraçant la rencontre historique entre Cartier et les Amérindiens, à Gaspé.

Article :

Jacques Cartier

Documents PDF

-

Le dévoilement du buste de Jacques Cartier

« Le dévoilement du buste de Jacques Cartier », La Patrie, 4 septembre 1934, p.19

Article :

Jacques Cartier -

Le lexique dressé par Jacques Cartier en 1534

Taille: 56 Kb

Article :

Jacques Cartier