Recent Articles

The Point: a Franco-American Heritage Site in Salem, Massachusetts

Traditional French Songs in Ontario

Fort William, Crossroad of a Fur Trading Empire

The Guigues Elementary School in Ottawa

Centre franco-ontarien de folklore (CFOF)

Centre de recherche en civilisation canadienne-française (CRCCF)

Articles

-

Adapting to Winter: Transportation

Winters in Quebec are long and harsh. When the first French immigrants settled on the banks of the Saint Lawrence, adapting to Quebec’s winter was a major challenge. Every aspect of day-to-day living was affected—agriculture and food supply, transportation, lodging, clothing, human relations, and culture. Amerindians were instrumental in helping the settlers to adapt. Then, as one generation gave way to the next, the ingenuity of the inhabitants and their determination to alleviate the hardships of winter led to the invention of ever more effective tools and equipment and the development of new ways of dealing with the harsh conditions. Today, Quebeckers can take part in most of the same activities year round—a situation that was still inconceivable not so long ago. Our gradual adaptation to winter marks our history and our heritage and provides the artifacts that fill our museums and our memories.

-

Association Canadienne Française de l’Alberta (ACFA)

In 2011 Alberta’s francophones comprised 2.2% of the province’s population. Protecting the French language in Western Canada has long been a struggle. As far back as 1926, Franco-Albertans formed an association to defend their interests and provide French-language education to the francophone population. Association canadienne-française de l’Alberta (ACFA) is active both on the ground in francophone communities and in provincial and federal politics where it has been instrumental in ensuring that Alberta’s francophone cultural heritage is preserved and passed on.

-

Brother André, Founder of Saint Joseph’s Oratory

Brother André, a man of the people, orphan, worker of modest means and humble brother of the Holy Cross, hardly seemed destined for great things. Yet for over a century, his name has been associated with one of the world’s biggest Christian shrines, Saint Joseph’s Oratory on Mount Royal in Montreal. Pilgrims flock to the basilica that he had built and masses are celebrated there daily. But in keeping with Brother André’s wishes, the hallmark of the Oratory is the care and attention paid to the sick and the suffering. Brother André’s compassion for others and the scope of his accomplishments are a valued part of Quebec’s cultural heritage.

-

Canadian National Vimy Memorial

The Canadian National Vimy Memorial is the largest monument to Canadian soldiers who gave their lives in the First World War. Located on Vimy Ridge in northern France, the memorial is the centrepiece of the park marking the site of the battle of the same name, which took place from April 9th to 12th, 1917. The monument also commemorates the sacrifice of Canadian soldiers whose graves are unknown. The history and symbolic importance of the Vimy Memorial andthe numerous commemorative ceremonies held there lend international importanceto this place of remembrance.

-

Cirque du Soleil (Origins): Les Échassiers de la Baie and the Baie-Saint-Paul Fête Foraine [Festival]

To date (2009), the Cirque du Soleil is without a doubt Quebec's most internationally renowned cultural enterprise. This undeniable commercial success is the fruit of projects that took place in Baie-Saint-Paul (in the Charlevoix region) in the 1980s. At the time society was ripe for such an experimental endeavour, particularly because during the 1970s in Quebec, a substantial part of the rising generation left urban population centres in search of a different worldwith different values. As a result, many "rediscovered" Charlevoix and Baie-Saint-Paul and since, the region has become a mecca for many hippies and migrant peoples. It was truly of a case of somewhere between "the Gaspé and all the way to California," to cite Pierre Flynn. 25 years after its humble beginnings in Charlevoix, this monumental cultural enterprise today known as the Cirque du Soleil has finally taken its rightful place in the history of the community of Baie-Saint-Paul and now it constitutes an important piece of cultural heritage for Quebec.

-

Citadel of Quebec

The Citadel of Quebec is the largest military fortification in Canada still in active service. Perched on top of Cap Diamant adjacent to the Plains of Abraham, it is an integral part of the city's old defensive works. The Citadel was built by the British in the early 19th century to protect Quebec City against American invasion. Today, it is the home of the Royal 22e Régiment of the Canadian Armed Forces and also houses an official residence of the Governor General of Canada. The Citadel of Quebec is recognised as a National Historic Site of Canada.

-

Félix Leclerc, Québec’s pioneering singer-songwriter

Félix Leclerc, already a highly-acclaimed author in the early 1940s, and well-known in particular for his trilogy, Adagio, Allegro and Andante, did not initially see himself as a singer-songwriter or chansonnier. The reason was simple: the French Canadian literary establishment saw no inherent value in the poetic character of Leclerc’s few early musical texts. For the literary pundits of the time, such songs could at best be considered in the same category as French music hall ditties, a genre they considered frivolous, or else folk music, which they looked down on. It was the response in France to Félix Leclerc’s songwriting and performing style that transformed perceptions of his “poetry given voice”. Leclerc was a pioneer who opened the way for the concept of “songs with content”, and in fact gave legitimacy to this way of singing which would become so popular in France, in Québec and all across French Canada.

-

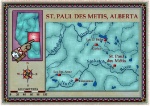

From Saint Paul des Métis to Saint Paul: A Patch of Franco-Albertan History

The year 2009 marked the centennial of the year in which Saint Paul des Métis was opened to French-Canadian colonization. While the community had existed since 1896, it is interesting to note that it is the anniversary of the arrival of French Canadians in the region that is celebrated, while the Métis background of the community is passed over in silence. The decision to open this Métis colony to French Canadians has been the subject of debate among historians over the years, but for the Métis families who were compelled to leave Saint Paul to settle elsewhere, the event has left lasting scars. Over time, Saint Paul became a dynamic community determined to preserve the town’s French language and francophone culture, but also a town known for its multiculturalism.

-

Montreal Canadiens; a Religion

The Université de Montréal announced in January 2009 it would offer a 16-week graduate course to future clerics called "The Religion of the Montreal Canadiens," and instead of poking fun at the ivory tower of academia, the media took the question quite seriously. Two months later, when word came out that the cash-strapped American owner of the Canadiens had put the team up for sale, the news was met with even more serious soul searching, if not a widespread spiritual crisis. The speculation was that Quebec-based saviours such as Cirque du Soleil's Guy Laliberté and René Angelil would come to the rescue of the faith. In a short time, these two events suggested that the Canadiens were much more than a hockey team, but rather, an essential component of Quebec identity in the way the Catholic Church used to be. The Canadiens' very existence provides a meaning of life for millions - for the game, its heroes and their fans do indeed make up a sort of "secular religion".

-

Mount Royal: The Importance of Civic Engagement

Mount Royal is part and parcel of Montreal’s history and identity. Dominating the city, “the mountain,” as Montrealers affectionately call it, has traditionally been—and continues to be—a geographical landmark and heritage symbol melding nature, culture and history. At 232 meters in height, the small Monteregien Hill named by Jacques Cartier in 1535 in honour of the King of France, and coiffed with a cross by de Maisonneuve in 1643, has long held a special place in the hearts of Montrealers. Their indefatigable efforts to protect it over the past 150 years testify to its powerful defining influence. And their civic engagement also bears witness to the key role that the public can play in preserving and promoting our collective heritage.

-

Orléans: A Franco-Ontarian Suburb

In a mere forty years Orléans has gone from an overwhelmingly French-speaking village to a suburb of Ottawa where scarcely one-third of the population has French as its mother tongue. Nonetheless, the French presence remains vibrant and local francophones are exceptionally dedicated to preserving their language and culture and building on their achievements. No other place in Ontario boasts cultural programs and facilities like those that serve Orléans’ francophone community. The fight twenty years ago to have the provincial government spell “Orléans” with the accent on the “e” is an eloquent example of the community’s determination to stand up for its rights with regional and provincial authorities.

-

Private French-language Radio in Manitoba

Not enough attention has been paid to the struggle to develop French language radio in Manitoba and the resulting victory. Nevertheless, these efforts constitute an important and necessary step towards the preservation of French culture in Manitoba. French-language radio was an important milestone for the defence, development and affirmation of Franco-Manitoban identity. Thanks to initiatives such as this one, the French-speaking people of Manitoba were able to preserve their cultural and artistic heritage despite the daily overwhelming onslaught of English on radio.

-

Quebec City’s Cantilever Bridge

The Pont de Québec [Bridge] has left its mark on the history of transportation and engineering in Canada. It is the world's longest cantilever bridge, with 549 metres of clear span between its main pillars; it exceeds the Firth of Forth Bridge near Edinburgh, Scotland, by 28 metres. At the beginning of the 20th century, the promoters of the Quebec Bridge project described the endeavour as the future eighth wonder of the world, particularly because its construction represented such a colossal challenge for the era. In fact, this feat of civil engineering was accomplished with great difficulty, and that, only after decades of expectation and two unsuccessful attempts that caused the death of 89 workers. The Quebec Bridge was, at last, successfully completed on September 20th, 1917, as over 125,000 spectators watched enthusiastically. Today it is considered as a world-class engineering masterpiece and has been designated as an International Historic Civil Engineering Landmark and a National Historic Site of Canada.

-

St. Lawrence Beluga

Since the 1980s, both individuals and communities of researchers have raised their voices in a cry of alarm, calling out for the protection of the St. Lawrence beluga. During this period, this loveable little white whale has become a global symbol of endangered wildlife. Today the beluga is the focus of numerous scientific studies, and although several measures have been put in place to protect it, the species is still in danger of extinction. This, however, has not always been the case. In 1920, for example, a bloody struggle was undertaken to reduce the number of belugas, because at that time, they were considered to be the enemy of the fishing industry. The whales were thought to devour large quantities of cod and salmon and other kinds of fish of commercial value. And so the role of the beluga in the life of the communities established along the St. Lawrence River has changed considerably over time, and what was once a natural resource to be exploited has become a heritage to be preserved.

-

The Acadian Games and the Growth and Development of the Acadian Community

The year 1979 was a significant one in Acadia: not only did the nation celebrate the 375th anniversary of its founding, but the famous Tintamarre – held on August 15th – was born and permanently established. In addition to that, two important social networks were created: the Conseil économique acadien – which will later become the Conseil économique du Nouveau-Brunswick – and the Jeux de l'Acadie. As Daniel O’Carroll wrote in 1993, these represent “the most popular annual event and one of the greatest achievements of modern Acadia.” Indeed, the Jeux represent a wonderful opportunity for Acadians of all ages to learn and excel. The Jeux were a major factor in the development of a modern Acadia full of talents and achievements.

-

The Cathedrals of Saint-Boniface

Since 1818, six churches have stood in succession in Saint-Boniface, Manitoba testifying to the longstanding French and Catholic presence in western Canada. The Red River town—now a borough of Winnipeg— grew by leaps and bounds over its first fifty years, from the humble Saint-Boniface Mission to the seat of a vast archdiocese covering most of western Canada. This growth led to the successive construction of five cathedrals. The largest and most prestigious, completed in 1908 under second Archbishop Adélard Langevin, was destroyed by fire in 1968, to the dismay of the francophone population for whom it was a symbol of strength. Today’s cathedral, consecrated in 1972, stands within the great edifice’s ruins, preserving the heritage value of a site that strongly symbolizes the francophone presence in western Canada.

-

The Chemin du Roy between Quebec City and Montreal

Today the Chemin du Roy, or King’s Highway, is a well known heritage route. Motorists along the north bank of the St. Lawrence River between Quebec City and Montreal can take Highway 138, which follows the approximate path of the original King’s Highway. Along the Chemin du Roy tourist route, blue signs guide drivers from town to village among the region’s heritage buildings and landscapes. Avenue Royale—which is a continuation of the original Chemin du Roy east of Quebec City—is yet a further occasion to visit and take in several additional heritage treasures. But the original King’s Highway, which was the first road to link Quebec City with Montreal was built in 1734. Along its winding course one can discover a condensed history of transportation in the St. Lawrence Valley.

-

The Habitation at Port-Royal, Acadia

Situated near the little town of Annapolis Royal in Nova Scotia, Port-Royal National Historic Site of Canada brings to life the French colony founded in 1605 by Pierre Dugua de Mons and his companions, including the famed Samuel de Champlain and the no less illustrious Jean de Biencourt de Poutrincourt et de Saint-Just. Visitors arriving at the site by Route 1 along the Annapolis Basin could easily mistake the fortified complex for the original construction, built in the early 17th century. In fact, the old buildings reminiscent of another time are actually a historical reconstruction dating from the late 1930s, the first of its kind in Canada.

-

The Montreal Olympic Stadium Complex

Unique in all of North America, the bold architectural style of the Montreal Olympic Stadium makes the building’s architecture one of the emblems of the City of Montreal. Designed by the French architect Roger Taillibert, in order to host the 1976 Summer Olympic Games, today the building has not only become a part of the architectural heritage of metropolitan Montreal, but also of the Province of Quebec and of Canada. Even though the general populace has a special affection for this piece of organic and sculptural architecture—which testifies to the international significance of an event that marked the rising of modernism in the Province of Quebec—many facets of the story how it was built and its short, but varied history remain unknown.

-

The schooner Saint-André, a jewel of the Charlevoix Maritime Museum

The schooner Saint-André was built in 1956 at La Malbaie, in Charlevoix County, by master carpenter Philippe Lavoie, one of the last schooner builders of the Saint Lawrence. Its owner, Captain Fernand Gagnon, engaged in coastal trading on the Saint Lawrence, mainly between Montreal and Sept-Îles, until 1976. At that time wooden schooners were replaced by metal ships, which were much larger, more profitable and better adapted to winter navigation. The Saint-André, one of the last witnesses to Quebec's particular long maritime tradition, was classified as a cultural property in 1978. Recently restored, it is conserved at the Charlevoix Maritime Museum, near the shores where it was born.