Tadoussac between Forest and Sea

par Carpin, Gervais and Équipe de rédaction de l'Encyclopédie

Tadoussac, lying at the confluence of the Saguenay and Saint Lawrence rivers, possesses a rich natural and cultural heritage. Originally a site for trade between Amerindian nations, it was later frequented by Basque, Breton and Norman fishermen. Its first permanent settlements were built in the first third of the seventeenth century. Tadoussac became New France's most important port, and the main trading post of the huge Domaine du Roi. Later, with industrialization and development of the region, its economic and touristic value grew. With its magnificent countryside, natural resources and history, Tadoussac makes its mark on land and on sea, as seen by the numerous heritage events still taking place today.

Article disponible en français : Tadoussac entre mer et forêts

Tadoussac today

Tadoussac enjoys a choice location. For centuries, it has attracted travellers, and it is still highly esteemed for its cultural and historical interest and for the opportunities it offers tourists and vacationers. Although the built heritage is no longer standing, some knowledge of history allows tourists visiting these sites to recreate the past in imagination, and to absorb the atmosphere of times gone by. A walk might lead to some half-hidden ruins, and spirits of ancient human presence may be evoked near the Centre des loisirs or at sites between Tadoussac and the Moulin-à-Baude dunes (NOTE 1), such as the Hovington farm lands, formerly called the Delporte farm.

Occupation through the ages

Human presence in Tadoussac goes back thousands of years. At the end of the Wisconsin glaciation about 10,000 years ago, melting snow and retreating waters on the North American continent gradually gave way to returning life: flora, fauna, and then human groups in search of food. Archeological excavations in the area around Tadoussac, which became accessible 2000 to 4000 years BCE, have revealed a great number of stone artifacts. Some of the objects from prehistoric times are now stored at the Quebec Ministry of Cultural Affairs in Quebec City.

Aside from stone artifacts, pottery with Iroquoian motifs has been found near the mouth of the Moulin-à-Baude River. This discovery corresponds to observations made by Jacques Cartier on his second voyage in 1535. Other reports from the 1540s, in Cartier's writings and in the judicial archives of the Basque country of Spain, suggest that the whole north shore of the Saint Lawrence River and of the Gulf of Saint Lawrence as far as Newfoundland, as well as the south shore as far as Gaspé, were frequented in summer by groups of Iroquoians from the greater Quebec region on hunting and fishing expeditions. There were not yet any Innu or other Amerindian nations there.

A meeting of cultures

In 1603, at Pointe-aux-Alouettes (located at Baie Sainte-Catherine on the west shore of the Saguenay), a French expedition including Samuel de Champlain met a group of Innu (probably including a few Algonquin and Etchemin) of about a thousand people, who decided to move their camp to Tadoussac to form an alliance with the French. At that time, Amerindians had been trading with Europeans on the banks of the Saint Lawrence at Tadoussac for at least thirty years. According to reports gathered in France by Thevet, a sixteenth-century historian, the Basques had erected a fortified house at Tadoussac (which he calls Thadoizeau) in the 1580s. The Saint Lawrence Iroquoian groups left this region after the 1640s, at an undetermined date and for unknown reasons that may have included wars, epidemics, or climate changes. Archaeological excavations have found proof of whaling in the region, mainly by Basque expeditions. Although no Basque sites, traces of camps, or ovens for melting whale fat have been found, it is possible that the bay was a place for exchanges among groups.

An Innu territory

During the three quarters of a century from the meeting of Basque fishermen with the first Saint Lawrence Iroquoian groups around 1580 until approximately the end of the 1640s, the Innu (or Montagnais) of Saguenay Lac-St-Jean jealously maintained, by violence if necessary, a monopoly on trade with the French. The French on their side quickly established a trading monopoly as well. Following a decline in their numbers due to epidemics, and a loss of social cohesion resulting from conversion to Christianity, the Innu were not able to maintain their monopoly against other Canadian, French and later English groups. The name Tadoussac (NOTE 2) is said to be a deformation of the Innu word tatouskak (breasts), a reference to the hills around the mouth of the Saguenay where whales come to feed.

The 1824 census lists three Innu families; only one family appears in 1891. After 1859, when the monopoly on exploitation of the territory ended, a number of families squatted on the Pointe de l'Islet, where they built houses on the rocks. They hunted belugas, fished, and built boats. There seem to have been many Metis among them. In the mid-twentieth century, it was reported that smells from these houses disturbed tourists at the Hotel Tadoussac, and as a result the squatters were evicted from the Pointe. Today a pleasant trail around the Pointe de l'Islet leads to this heritage area with its flora and fauna, but little remains to mark more than a century of rather less comfortable habitation.

From outpost to permanent settlement

For a long time Tadoussac was the outpost and main trade centre of a large territory assigned to the Domaine du Roi (the King's Domain, or as we would say today, the public domain), then to its English equivalent, the King's Posts, managed by the North West Company and finally by the Hudson's Bay Company. The principle of monopolies is important in Tadoussac's history, because one could say that until the King's Posts were abolished on 14 November 1859, settlement was not permitted in Tadoussac and all its hinterland, in that no concession could be granted to settlers, and no village could be founded.

However, the monopoly on exploitation of resources in effect before 1859 did not mean that Tadoussac was uninhabited. The post included five buildings in 1760 and fourteen in 1785. The people who lived there were company employees, not settlers. In 1785 a report mentions a chapel, a presbytery, a house, two stores, a forge, a bakery, a cooperage, a powder magazine, three sheds, a barn-stable and a stable, along with three cows, one ox and one horse. The employees not only worked in fur trading; they fished commercially for salmon, mackerel, herring and cod, and hunted porpoises for the oil trade. All the buildings were located along the terrace overlooking the beach.

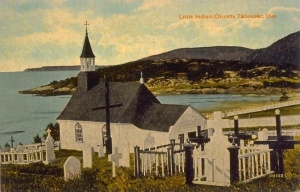

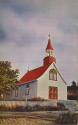

The first chapel and the first cemetery

More or less substantial traces remain from this period before the area was opened to settlers and the village was established. In the early 1640s a first permanent chapel was constructed to replace the seasonal chapel, built like an Amerindian cabin. It burned down in 1645. It is possible that the foundations of this building are the ones found under the former Girard house, near the dry dock. The whole area from the Tadoussac Hotel to the dry dock was probably the place where the Innu camped during the trading season. This spot is ideal because both it and the next hill overlook the Saguenay and the Saint Lawrence, and because trade goods were unloaded on the beach where the agent's post was located. The oldest residents of this part of Tadoussac can also tell about the discovery of human bones revealed by various earthmoving works. Beside the chapel there was no doubt a cemetery, used particularly in times of epidemics among the Amerindians and for the few French sailors for whom Tadoussac was the last port of call. It is probably not a pre-contact Amerindian cemetery, for these groups did not normally reside at their burial places. Artifacts that were found in excavations of what were probably the foundations of the first chapel, beneath the Girard house, are now at the Musée du Saguenay Lac-St-Jean in Chicoutimi.

The Chauvin House and the Chapelle Sainte-Anne

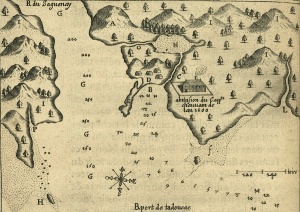

A recent reconstruction and an authentic heritage building are located to the east of this beach-front area: the reconstituted Pierre Chauvin trading post, and the small Tadoussac chapel. The trading post was described by Champlain, who had seen its ruins; he gave its dimensions, and showed its approximate location on his 1608 map. When William H. Coverdale, director of Canada Steamship Lines and a great amateur heritage collector, began reconstruction of the Hotel Tadoussac in 1941, very old foundations were revealed. Coverdale concluded that they were the foundations of the failed winter trading post of Chauvin's employees in 1600-1601.

Specialists pointed out that the dimensions of the foundations did not correspond to those described by Champlain, and that they might be, for example, from a trading building from the eighteenth or even the nineteenth century. Coverdale, foreseeing how interesting a presentation of the first 1600 trading post might be to tourists, brushed aside these objections, and had a building constructed on these foundations according to Champlain's descriptions. It will probably never be known exactly to what building the foundations belonged, but Coverdale gave the community a display space that enriches its heritage and provides an undeniable tourist attraction. The foundation stones were used to build the central fireplace of the building and can be seen today. With the second site, the Chapelle Sainte-Anne, we have an authentic heritage building dating from 1747-1750, classified as a historic monument in 1965, which is now an important stop on heritage walks through the village.

The monopolies end and a village is built

In the first half of the nineteenth century, a built heritage with industrial and agricultural functions was added to the commercial built heritage that had begun with the first trading post. Neither of these heritages has left more than very small tangible traces.

The British-born merchant William Price built a sawmill at Anse-à-l'Eau in 1838 (NOTE 3). No visible traces remain; it was probably located at the place where ferries land today. The sawmill included a dock, a mill, offices, houses and warehouses, with eighty employees and their families. For about ten years, a village that was not yet recognized as such stood there. The only store accessible to the employees belonged to Price, and although a chapel and a school were built, no property rights were granted to the employees. Soon the forests had lost their commercially valuable trees, and most of the employees were moved to a new sawmill built on the Petit-Saguenay River.

In 1843, as the most productive period of the Anse-à-l'Eau sawmill was coming to an end, a certain Thomas Simard, by building a second sawmill on the Moulin-à-Baude River, installed infrastructure that attracted part of the life and activities of what was to become the village of Tadoussac. Indirectly, construction of this mill finally justified the name given to the little river. Although the Moulin-à-Baude sawmill and the flour mill that complemented it provided work for only ten employees during three months of the year, this activity attracted farm families who settled on the plateau of what is today the top of the Tadoussac dunes (NOTE 4). This agricultural hamlet of Moulin-à-Baude, the forerunner of a permanent village, did not last. In 1861, with a population of 300, clearing of the forest and working of the thin layer of arable land turned the place into a desert of sand.

In 1874 the Anse-à-l'Eau sawmill was replaced by a government fish hatchery to restock the local salmon rivers. In 1900 this building was demolished to make way for another one, probably the building still occupied by the present-day fish hatchery, on the right side of the road before the ferry. The Simard mill, which was bought by Price in 1848, ceased its activities in 1890, and was replaced by a new sawmill that was in use until 1940.

The oldest remains of the Moulin-à-Baude sawmills were buried by a rockslide. For the more recent buildings, a 1940 mill and a hydroelectric power station built in the same year (in operation until the 1960s to serve Tadoussac and Sacré-Coeur), there remain some stones of the facade still standing behind the dune house, bits of wood and cement fragments scattered among the rocks leading down to the beach, and broken remains of concrete blocks at the beginning of the path from the beach up to the dune house. A little further from Tadoussac, beyond the dunes, in the inlet beyond the Moulin-à-Baude Bay, the vestiges of three lime kilns used at the turn of the twentieth century can be seen. It is fortunate that access to them is difficult, for this archaeologically valuable site is not yet sufficiently protected from the damage that large numbers of visitors would cause.

Tadoussac, a tourist destination on land and sea

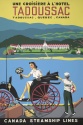

Tadoussac's location has made possible its rich touristic heritage. For a century from 1860 to 1960, the big white passenger steamboats going from Montreal to above the Saguenay brought tourists or summer residents; in summer, there was a ship every day. Lighter craft such as sail or motor schooners also transported merchandise and passengers until the middle of the twentieth century. With the reign of the automobile, the only watercraft still used today to transport tourists are the ferries that cross three times a hour from one bank of the Saguenay to the other, carrying cars, motorcycles and trucks.

Tourism, depending as it did on the white boats and schooners, began in the early 1860s and grew five or six years later with construction of the Hotel Tadoussac. The visitors were rich English-speaking families from Quebec City and Montreal, as well as American families. The leaders were the Price family. Other visitors built summer houses rather than staying at the hotel.

In addition to the residence of Governor General Lord Dufferin, behind the little Chapelle Sainte-Anne, there are the Price houses including two properties located directly west of the Chauvin house, and the houses built on the rocks of Pointe de l'Islet. The anglophone community, still recognized as such today, occupies the family houses seen across from the golf course along the Rue des Pionniers or in the Parc Languedoc, and they have a Protestant chapel.

Today, one of Tadoussac's best-known tourist activities is whale watching, which began in the 1970s and has become extremely popular. A visit to the Sea Mammals Interpretation Centre shows that the presence of whales has long been an integral part of Tadoussac: in the past they were one of the reasons for Europeans to come to North America, and they are now one of the main tourist attractions.

An evolving heritage

With its scenery and its historic buildings, Tadoussac shows how heritage evolves, changing along with changing human activities. Of course, visitors today cannot see the dock that served Anse-à-l'Eau, but the present-day ferry dock and the dock for whale-watching boats bear witness to this dynamic character. Heritage descriptions may soon include the Tadoussac Song Festival (whose 30th edition will take place in 2013) and the whale-watching excursions, to name only two activities, which will enrich this centuries-old heritage at the meeting of land and sea.

Gervais Carpin, Historian

Additional DocumentsSome documents require an additional plugin to be consulted

Images

-

Affiche promotionnell

Affiche promotionnell

e «Une Croisièr... -

Ancien four à chaux,

Ancien four à chaux,

Tadoussac -

Ancienne chapelle de

Ancienne chapelle de

Tadoussac, 1898 -

Arrivée des bateaux d

Arrivée des bateaux d

e pêche à Tadou...

-

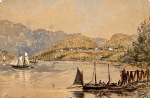

Baie de Tadousac, 188

Baie de Tadousac, 188

0 -

Baleine à Tadoussac,

Baleine à Tadoussac,

2006 -

Beluga (Delphinapteru

Beluga (Delphinapteru

s leucas), Tado... -

Carte montrant le por

Carte montrant le por

t de Tadoussac,...

-

Cottage de Lord Duffe

Cottage de Lord Duffe

rin à Tadoussac... -

Église amérindienne,

Église amérindienne,

Tadoussac, Qué.... -

Expédition aux balein

Expédition aux balein

es à proximité ... -

Fac-similé d'une plaq

Fac-similé d'une plaq

ue en plomb tro...

-

Falaise près de la pl

Falaise près de la pl

age des dunes à... -

Hôtel Tadoussac

Hôtel Tadoussac

-

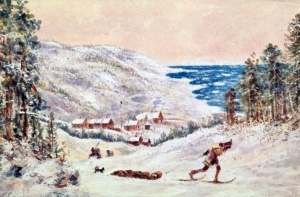

La baie de Tadoussac

La baie de Tadoussac

en 1870 -

Le port du Roi, Tadou

Le port du Roi, Tadou

ssac, 1842

-

Le Village, Tadoussac

Le Village, Tadoussac

, Qué. -

Quelques vues du Sagu

Quelques vues du Sagu

enay et de Tado... -

Reconstitution du pos

Reconstitution du pos

te Chauvin à Ta... -

Tadoussac (Canada): l

Tadoussac (Canada): l

a petite chapel...

-

Tadoussac, 1863

Tadoussac, 1863

-

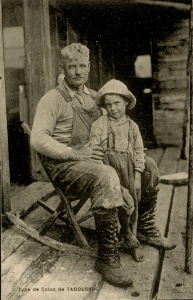

Type de Colon de Tado

Type de Colon de Tado

usac [sic] -

Une famille de Montag

Une famille de Montag

nais à Tadoussa... -

Une scène de rue, Tad

Une scène de rue, Tad

oussac, P.Q.

-

Vieille église amérin

Vieille église amérin

dienne de 1747,... -

Vue de Tadoussac à bo

Vue de Tadoussac à bo

rd du traversie... -

Vue générale de Tadou

Vue générale de Tadou

ssac, 1879 -

Vue générale de Tadou

Vue générale de Tadou

ssac, 1898

Document PDF

Catégories

Notes

1. The name Moulin-à-Baude may be a deformation of the expression "môle Baude", the môle being a place to drop anchor sheltered by a jetty, since there was no mill at this place before the 1850s. This suggestion is supported by Champlain's observation that boats had a very safe place to anchor before entering the Tadoussac harbour.

2. The name Tadoussac, with spellings that varied with authors, was no doubt used by sailors from the second half of the sixteenth century, and may have appeared on maps that have been lost. Its first known use is in Champlain's first account when his expedition anchored there and stayed from 24 May to 18 June. His map of Tadoussac and the mouth of the Saguenay, including Pointe aux Alouettes to the west and the bay of Moulin-à-Baude to the east, dates from 1608. It was published in his 1613 edition.

3. A pragmatic alliance between Charlevoix settlers who wanted to obtain lands on the North Coast at Saguenay and Lac-St-Jean, and forestry entrepreneurs who wanted to exploit the region's forests, led the Société des Vingt-et-Un (a group of Charlevoix heads of families) to purchase timber rights from the Hudson's Bay Company in 1837. The Société sold its logs to William Price, in exchange for transporting and provisioning settlers.

4. The 1851 census lists thirteen small concessions of 5 to 23 acres; the thirteen families include a total of about a hundred people. Despite sand skiing in the mid-twentieth century, the more recent motorized vehicles and the many visitors, one can still sometimes on a walk in the dunes pick up a piece of pottery or metal, the only known remains of this hamlet. It is hard to imagine the forty or so farms where 300 people lived, including perhaps two hundred children, and all the activity generated by the settlement. A few rare photos show that it did indeed exist.

Bibliographie

Beaty, Bennie, Tadoussac, les sables d’été, Montréal, Price Paterson Ltd, 1995.

Cartier, Jacques, Relations, édition critique par Michel Bideaux, Montréal, BNM, Presses de l’Université de Montréal, 1986.

Champlain, Samuel de, Œuvres, dans Charles-Honoré Laverdière, Œuvres de Champlain, Montréal, Éditions du Jour, 3 vol., 1973.

Dubreuil, Steve, Réactualisation de la recherche historique, Tadoussac, Municipalité de Tadoussac, 2010.

Dufour, Pierre, La peau des autres : traite de peletries à Tadoussac, Tadoussac, Municipalité de Tadoussac, 2 vol., 1988.

Hamel, Nathalie, La collection Coverdale, Québec, Presses de l’Université Laval, 2010.

Marie de l’Incarnation, Correspondance, dans Dom Guy Oury, Marie de l’Incarnation, ursuline (1599-1672), Solesmes, 1971.

Moss, William et Michel Plourde, Inventaire archéologique en la municipalité de Tadoussac, Tadoussac, Municipalité de Tadoussac, 2 vol., 1986.

Picard, François, Tadoussac. Étude ethno-historique et étude potentiel archéologique, historique et préhistorique, Québec, Ministère des Affaires culturelles, 2 vol., 1983.

Villeneuve, Gaby, Tatoushak, Grandes-Bergeronnes, Atelier de communication inc., 1982.