Parc national de Miguasha

par Charest, France

Parc national de Miguasha is one of the world’s most prestigious fossiliferous sites. Thousands of fossils of fish, plants, and invertebrates some 380 million years old have been discovered there. UNESCO added this natural site on the Gaspé Peninsula to its World Heritage List on 4 December 1999. But well before being recognized as a world treasure, this site had long been a part of the daily life of the inhabitants of Miguasha who collected fossils. Indeed, these people were tremendously helpful to the scientists who began to appear in their region at the beginning of the 20th century. Scientists still take an active interest in the site, and the park’s team of paleontological researchers continue to gather new specimens from the now-famous cliff. Some of these marvellous fossils are on display in the permanent exhibition of the Miguasha Museum of Natural History located on the very site where they were discovered!

Article disponible en français : Parc national de Miguasha

The Miguasha Museum of Natural History

Few fossiliferous sites have the

opportunity to exhibit their star pieces in a museum located right on the site

where they were discovered. The

Miguasha Museum of Natural History (Musée d'histoire naturelle de Miguasha), a stone’s throw away from the fossiliferous cliff,

is one of the lucky few. Visitors to the museum can learn about the fossils,

including how they were discovered and how they were organized in a collection,

while enjoying an introductory overview of the scientific research carried out

on these fossils.

At the heart of this museum, which was expanded and renovated in 2002–2003, lies

the exhibition room where the fossiliferous treasures are presented to their

best advantage in a modular exhibition that can be updated and modified to stay

in tune with the ongoing research carried out on the site. Visitors are thus

apprised of new discoveries shortly after they are unearthed. The exhibition includes

a variety of sections on such topics as the Miguasha paleoenvironment, the

fossilization process, the human history of the area, research projects and of

course the different fossil species that lived here some 380 million years ago.

The museum is also equipped with a research centre made up of three collection

rooms, two fossil preparation labs, a darkroom and a research room. The main

collection, also called the “national collection,” boasts over 9,000 fish fossils, some

1000 plant specimens, and several dozen invertebrate specimens (90 at this

writing). As for the stratigraphic collection, it contains thousands of fossil

specimens that help to reconstitute the history of the Gaspé Peninsula and Quebec through different geological periods. And finally, type specimens collection was

designed to house all specimens that have served as references in scientific

publications.

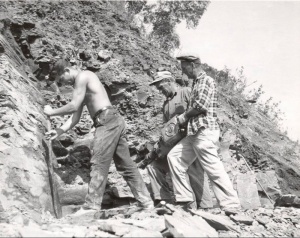

Every summer, the park’s research staff carry out digs on this exceptional

fossiliferous site. These digs aim to unearth new specimens or, better still,

new species, and to give scientists a better understanding of the Miguasha paleoenvironment.

In addition, members of research staff collaborate from year to year with

paleontologists around the world who either borrow specimens or come to the

site to do their research.

Miguasha’s Geological Heritage

The territory encompassed by Parc national de Miguasha is a narrow strip of land two kilometres long that runs along the coast and covers less than one square kilometre. It is on the western side of Miguasha Point, on the Gaspé Peninsula. This hilly point of land, which separates the fresh water of the Ristigouche River from the salt water in Chaleur Bay, is known for its beautiful landscapes.

The geological

history of the Miguasha cliff is closely related to that of the Appalachian

Mountains, which were formed about 400 million years ago during the Devonian geological

period (from 416 million to 359 million years ago). The sediment that makes up

the cliff is the product of the erosion of these once-gargantuan mountains. At

that time, sediment was carried by rivers and streams. Over time, the deposits

of sediment built up and were compacted into a vast paleoestuary. The fish,

plants and invertebrates that lived in or around this estuary were part of this

slow process. The sedimentary and fossiliferous layers, initially horizontal,

have since undergone a series of morphological changes caused by the effect of

tectonic forces exerted on the Earth’s crust. The resulting geological

formation was called the Escuminac Formation. Its layers of sandstone and argillaceous

rock are exposed in a cliff that now stands some 30 metres above the

present-day level of the estuary.

A second formation—the Fleurant Formation—is also exposed in some places on the

Miguasha cliff. The Fleurant Formation, which predates the Escuminac Formation,

and therefore lies beneath it, is a conglomerate—that is, an assemblage of

pebbles of various sizes held together by sand. This formation was likely the

bed of an ancient river with a high rate of flow that probably predated the

more gently flowing paleoestuary.

Although it does not lie within the boundaries of the park, the Bonaventure Formation adds to the charm of Miguasha Point with its surprisingly flamboyant dashes of red. This formation, exposed at several spots along the cliff—as well as elsewhere on the south coast of the Gaspé Peninsula—is a conglomerate from the Carboniferous Period (359 to 299 million years ago). Its red colour, resulting from oxidation of the iron contained in the sediment, is what gave Miguasha its name, Miguasha being derived from the Mi'kmaq word megwasag, meaning red earth or red cliff.

Miguasha and Quebec’s Scientific Heritage

For over 100

years, from 1879 into the 1980s, as many as 8,000 fossils were gathered from

the park’s current location then studied in various museum-related and academic

facilities around the world, where they are still kept. Scores of important

articles have been written by foreign scientists on the fossils of Miguasha.

With the creation of a conservation park in the 1980s, the site became a hub

for research activity and was no longer simply the place where specimens were

gathered. Creation of the park meant that all fossils would henceforth be

preserved at Miguasha, and foreign establishments, such as universities and

museums, would have to work with the park’s staff in order to gain access to

the site. This new way of doing things has been the basis for numerous international

collaborations involving park research staff and researchers from all over the

world. These collaborative endeavours have provided opportunities to train a

whole new generation of Quebecois palaeontologists who are at last able to take

an active part in research activity.

There are very few universities in Canada that offer studies in paleontology.

In Quebec, the only existing program is a Canada Research Chair in Vertebrate

Paleontology at McGill University. For this reason, the majority of Quebecois

palaeontologists were trained in the United States or Europe. However, there is

a project underway involving a favoured-partners arrangement between Parc national de Miguasha and L’Université

du Québec at Rimouski, which will foster research carried out in Quebec by

French-speaking students. A brand new generation of paleontologists is already

being trained, laying the way for a bright future for Quebec-based

paleontological research. This promises to yield a dynamic and diversified body

of research that ranks among the world’s best, and Quebec will thus be in a

position to have a greater impact in the field of paleontological research

internationally.

Discoveries of the Miguasha Site

Before the

first European settlers arrived in the 18th century, Miguasha Point

was a crossing point for the Mi'kmaqs, a nomadic aboriginal people that

frequented the area. The British were the first to establish a European

presence in Miguasha following the 1760 Conquest. Then, in 1855, the abolition of

the seigniorial system provided favourable conditions for many Acadians to

settle in the area.

The earliest discovery of fossils in Miguasha was made in 1842 by New Brunswick

provincial geologist Dr. Abraham Gesner. Despite its inclusion in a report,

this discovery fell away into obscurity. Miguasha gained renown, not with the

1842 discovery, but rather, when the site was rediscovered in 1879 by Robert W.

Ells, a geologist for the Geological Survey of Canada. The first organized digs

took place in the years that followed, and the first writings describing the

fossils of Miguasha were published in 1880–1882. Following these publications, many

teams of scientists came from Europe and the United States to gather thousands

of specimens, which are now preserved in museums around the world.

Local Collectors

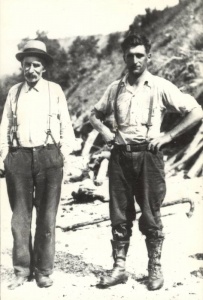

The first scientists who had come to take samples were welcomed by families in Miguasha, among them the Plourde family. Antoine Plourde, who was 19 at the time of the 1879 discovery, guided foreign scientists to the cliff’s richest fossil layers. He even guided a group of scientists during the 12th International Geological Congress in 1913. On this occasion, he had set out his finest specimens on tables on the beach. They went like hotcakes! By this time, Antoine’s son Euclide Plourde had also developed a passion for the cliff and its fossils, and he took part in the digs alongside the scientists.

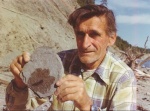

Another family, the Landrys, offered room and board to visiting scientists for a dollar a day. They also collaborated with the scientists on research. Indeed, it was Mr. Joseph Landry who sold one of the most exceptional specimens of the species Eusthenopteron foordi, also known as the Prince of Miguasha, to the scientists of the Swedish Museum of Natural History in Stockholm (Sweden). This specimen, preserved in three dimensions, which was sold for $50 in 1925, was studied for 25 years and yielded many discoveries on the anatomy of this species.

The Quebecois Discovery

It was not until 1937 that Quebeckers who were not residents of Miguasha—namely Léo-Georges Morin of l'Université de Montréal and Reverend J.W. Laverdière of Laval University in Quebec City, both geologists—visited the site. Upon their arrival in Miguasha, they were intrigued by a sign offering “Fossils for sale,” which led them to the Plourde family home. These two academics then learned that the site was the summer destination of several foreign scientists. They immediately notified Quebec provincial government officials, and René Bureau, who was at that time a technician for Quebec’s Department of Natural Resources (now called the Ministère des Ressources naturelles et de la faune), was given the mandate to compile the first Quebecois collection of Miguasha fossils. During his expeditions to the site, Mr. Bureau received help from Joseph Landry, who provided him with a place to stay, and Euclide Plourde, who acted as his assistant and guide.

Actions Taken to Protect and Enhance Miguasha Fossils—1937 to Present

René Bureau lost no time in issuing recommendations on how best to preserve the Miguasha fossiliferous site. However, with the outbreak of World War II, the government’s priorities quickly shifted. Mr. Bureau was not to renew his efforts to achieve protected status for the site until the 1960s. In 1972, land adjacent to the cliff was purchased at last, thanks to a joint effort by Mr. Bureau and Quebec’s department of tourism, hunting and fisheries (Ministère du Tourisme, de la Chasse et de la Pêche). In 1975–1976, management of the site was entrusted to l'Université du Québec at Rimouski, whereupon a team came to gather specimens for the purpose of establishing a collection. Responsibility for managing the site was returned to the ministry in 1977. At this time, Marius Arsenault, who was completing a master’s degree in paleontology, was appointed head of a new team that gathered newly unearthed fossils and established an interpretive facility. The first museum, then, opened its doors in June 1978, thanks to a concerted effort by Mr. Arsenault’s team, René Bureau and a citizen committee. Henceforth, guided tours of the exhibition and the cliff were available to visitors. These guided tours have become a tradition and are available to the general public to this day!

In 1985, the

concerted efforts to establish a conservation park finally came to fruition,

and the importance of this fossiliferous site in the natural heritage of Quebec

was thus officially recognized.

Subsequently, in 1991, the museum underwent an expansion, which included

the addition of an initial official collection room, where fossil samples taken

from Miguasha since 1975 were repatriated to be housed in a single location. In

the same year, the 7th International Symposium on Early and Lower

Vertebrates, an event of international importance, was held in the new museum.

There was still one major accomplishment that remained to be realized: the

park’s inclusion in the UNESCO list of World Heritage sites. This idea had been

tossed around since the late 1970s, for Marius Arsenault, the park’s director

from 1977 to 2003, remained convinced that the site was worthy of this

distinction. Indeed, he was one of

the first people to take an active interest in the file. Creation of the conservation

park was a crucial prerequisite, but there was still much work to do and many

people to persuade. For a fossiliferous site to be included on the list, it

must be shown to be objectively the best such site in the world for the fossils

of a particular geological period. A sweeping study was therefore undertaken by

two paleontologists—Dr. Richard Cloutier, from Quebec, and Dr. Hervé Lelièvre, from

France—to compare some 15 important fossiliferous sites representing the

Devonian period, according to a new set of criteria set forth by the International

Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) and UNESCO. This study showed that the

Miguasha fossiliferous site stood out from all of the other Devonian sites.

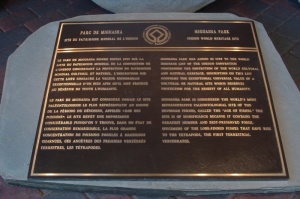

This considerable effort led to registration of Parc national de Miguasha as a UNESCO

World Heritage natural site on December 4, 1999. Since this time, the park and

the museum have continued to grow and to attract ever-increasing numbers of

visitors. In 2007, one of the first individuals to have worked to protect the

site was honoured when the famous fossiliferous cliff at Miguasha was

officially named Falaise René-Bureau.

Efforts to protect the site, undertaken as early as 1937, contributed

ultimately to preserving this unique treasure of our natural heritage for

present and future generations. The park’s current staff continue to work with

unflagging passion to protect this exceptional site and to present it in its

best light, accomplishing this through their research and through updates and

improvements to the outreach and education program made available to the

approximately 24,000 people who visit the site each year.

France Charest

Co-Manager of Conservation and Research

Parc national de Miguasha

Bibliography

Cloutier, Richard et Hervé Lelièvre, Étude comparative des sites fossilifères du Dévonien, Ministère de l'Environnement et de la Faune du Gouvernement du Québec, 1998, 88 p.

Cloutier, Richard, Le parc de Miguasha : De l'eau à la terre, Publications MNH Inc., Collection In Situ 3, 2001, 143 p.

Cournoyer, Raymond, Parc de Miguasha : Le plan directeur, Ministère de l'Environnement et de la Faune du Gouvernement du Québec, Direction des parcs québécois, 1998, 88 p.

Schultze, Hans-Peter et Richard Cloutier (Éds), Devonian Fishes and Plants of Miguasha, Quebec, Canada, Verlag Dr. Friedrich Pfeil, München, 1996, 374 p.

«De l'eau à la terre : Le parc national de Miguasha», Société des établissements de plein-air du Québec (SEPAQ), site consulté le 23/04/09 [en ligne], http://www.sepaq.com/pq/mig/miguasha/

Additional DocumentsSome documents require an additional plugin to be consulted

Images

-

Antoine Plourde et so

Antoine Plourde et so

n fils Euclide ... -

Certaines roches argi

leuses de la fo... -

Coup d’œil sur l’expo

sition permanen... -

Euclide Plourde en 19

Euclide Plourde en 19

76. Il est rest...

-

Gravure d'un fossile

Gravure d'un fossile

-

L’équipe de fouille à

L’équipe de fouille à

l’œuvre!... -

La collection nationa

le avec ses cab... -

La falaise fossilifèr

e de Miguasha e...

-

La plaque dévoilée en

juillet 2000 p... -

La visite guidée de l

’exposition per... -

Le musée d’histoire n

aturelle de Mig... -

Le musée d’histoire n

aturelle de Mig...

-

Le musée d’histoire n

aturelle de Mig... -

Le pavillon d’accueil

du musée d’his... -

Le premier musée, ouv

Le premier musée, ouv

ert en 1978 -

Le travail du prépara

teur, qui netto...

-

Les fouilleurs au tra

vail -

Lors des fouilles, ce

Lors des fouilles, ce

rtaines roches ... -

Moulage d’un spécimen

Moulage d’un spécimen

3D de l’Eusthe... -

René Bureau (droite)

René Bureau (droite)

accompagné de E...

-

Un magnifique spécime

Un magnifique spécime

n 3D de l’Eusth... -

Un site de fouilles s

ystématiques où... -

Vue aérienne du musée

d’histoire nat...