The French Language in Manitoba: French-Canadian and European Roots

par Hallion Bres, Sandrine

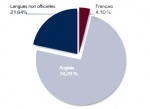

According to the 2006 census, Manitoba residents whose mother tongue is French account for slightly less than 4% of the province’s overall population. The history of the French language spoken in Manitoba, surviving through stubbornness and a wilful activism for the conservation of its cultural and linguistic particularities, nonetheless bears the imprint of the rich and varied origins out of which it has grown. The varieties of French used by the French-speaking community in Manitoba still bear the marks of their linguistic forebears—regional varieties of French brought to Manitoba by settlers who had come from Quebec or from French-speaking Europe in the early years of the 20th century.

The Fragility of Linguistic Diversity

Languages are nonmaterial treasures to be protected. Various actions undertaken by UNESCO to preserve linguistic diversity around the world (NOTE 1) are evidence of this organization’s adherence to this principle. While the French language, with its history as an instrument of colonial domination, its present-day status as an international language, and its status as a language spoken by millions of people worldwide, cannot truly be considered to be endangered, its status as a minority language in certain locations is nonetheless a source of some concern. Such is the case in Manitoba, where the influence of English often reduces the range of contexts in which French speakers actually speak French—and indeed leads some members of the population to abandon French usage altogether. Moreover, the promotion of a standard, more prestigious variety of French, carried out primarily by educational and cultural institutions and by French-language media, has tended to erase some particularities specific to vernacular varieties of French. Yet these inherited linguistic traits provide information on the cultural specificities of a particular segment of the population while making an essential contribution to maintaining the desire among French speakers to perpetuate their own language, along with its emotionally emblematic and culturally identifying linguistic attributes. In a word, the French language in Manitoba is faced with a twofold threat—the threat of assimilation of French speakers into the English-speaking majority, and the threat of extinction of local varieties of French that are often intertwined with values in regard to stylistic characteristics and speakers’ sense of identity.

French speakers in Manitoba: A Few Historical Reference Points

To an outside observer, the province of Manitoba is not at first glance the most visible symbol of the French-speaking world in North America. Yet from the time when the very first settlers settled along the banks of the Red River at the beginning of the 19th century, the French language has played an integral role in the history of Manitoba. When Manitoba entered the Canadian Confederation in 1870, the majority of the population were French speakers, primarily of Métis heritage, and the fledgling province was officially bilingual. However, over the next 20 years, the proportional demographic heft of this group would steadily decline in the face of mass immigration from Ontario and non-francophone countries. In 1891, French speakers had already become a small minority—comprising less than 10 % of the population of the province—with very little clout. Moreover, as the 20th century progressed, French speakers would experience an ongoing series of setbacks due to linguistic policies that were not conducive to the survival of the French language in Manitoba. In particular, the abolition of French in the legislature and in the courts (1890), then in schools (1916), would contribute to the decline of public French usage in Manitoba. This left French speakers feeling guilty or unjustly treated, or both, and led to assimilation of those who were disinclined to fight for the right to speak French while redoubling the determination of the feistier members of the French-speaking population. This tension persisted until the officialization of bilingualism at the federal level in the 1970s. Today, the French-speaking community has recovered its constitutionally protected language rights, and French enjoys institutional support that allows it to extend its reach beyond the sphere of family life in private homes.

Immigration of French Speakers, 1870–1920

The ancestors of the core members of today’s Franco-Manitoban community came to put down roots and, in most cases, work the land, during the period from 1870, when Manitoba became a province, to the end of World War I. The Catholic clergy, which prior to 1870 had already played a vital role in bringing settlers to the Red River Colony, continued after this date to be actively involved in organizing immigration of French speakers to Manitoba. In 1870, the francophone Métis group that had settled in the colony still tended to prefer a semi-nomadic way of life that involved a westward migration during buffalo hunting season. For this reason, but also due to the discriminatory treatment inflicted upon them by new arrivals, most Métis left the lands that they occupied in Manitoba to settle farther to the west.

The French-speaking population was replenished in the period from 1870 to 1890 as initiatives taken by the clergy to encourage francophone colonization attracted many immigrants. Recruiters directed their efforts primarily towards Quebec and New England, where a great many Quebecois had gone to find work in the textile industry, and towards states in the American west (such as North Dakota and Minnesota), where some French Canadians had gone to continue farming on lands that seemed well suited to agricultural development.

Le Colonisateur Canadien—a newspaper first published by the Canadian Pacific Railway, then run by the reverend Charles-Agapit Beaudry, a colonizing priest from Saint Hyacinthe, Quebec—was one of many recruitment organs at use in these regions at this time. In January 1874, La Société de Colonisation du Manitoba was founded on the initiative of the clergy, which favoured a system of reserves for populating Manitoba. The purpose of such a system was to safeguard cultural and religious cohesiveness among new arrivals, who would group together, then, in small perishes to the south of Winnipeg, two notable examples being Sainte Agathe and Notre-Dame de Lorette (present-day Notre Dame Parish in Lorette, Manitoba). This way of populating the province, by fostering concentrated enclaves of French-speaking Catholics, contributed to strong homogeneity among French speakers within the rural communities that were springing up during this period, and helped to ensure cultural and linguistic survival despite a dwindling francophone population.

Beginning in 1890 and continuing into the 1920s, it was primarily French-speaking immigrants from Europe that would make a modest but steady contribution to filling out the ranks of the francophone population of Manitoba. Colonizing missionaries were sent to the Old World, where they worked alongside the agents of La Société d’Immigration Française. This organization, which planned to make Manitoba a French-speaking province, vaunted the agricultural merits of the region in a brochure distributed in France, Belgium and Switzerland (NOTE 2). Additionally, collections of propaganda letters in which settlers recounted their experiences were published and distributed in Europe. Notre Dame de Lourdes, founded by Father Paul Benoît in 1891, was one of the so-called French parishes established in Manitoba during this period. Numerous settlers who settled in this community and in the neighbouring parish of Saint Claude hailed from the French regions of Jura (Father Benoît’s native region), Savoy, and Brittany.

Varieties of French Spoken in Manitoba—European and Quebecois Roots

At the end of the 19th century, life in rural Manitoba was defined by toil, privation and isolation. The latter (isolation) is of particular importance, as it provided a favourable environment for maintaining French as the everyday language of families living on isolated farms and in rural communities with a strong French-speaking majority. In these places, social life took place under the watchful eye of the Franco-Catholic clergy, despite the predominance of English province-wide and the absence of political support for the French language. Isolation was also a factor in the preservation of the vernacular traits of spoken French dialects that continued to be imported to Manitoba into the 1950s. At this time, the urbanization of the province began to attract numerous French speakers to Winnipeg, leading to the disintegration of protectionist and homogeneous parochial structures affecting religion, culture and language. As a result, the proportional demographic importance of French speakers in rural Manitoba underwent significant change.

These new social factors would have a marked impact on the rate at which French speakers became English speakers, as suggested by the discourse of Gaston Dulong, who analyzed the state of the French language in Manitoba at the beginning of the 1960s (NOTE 3). Dulong painted a very dire picture of the French-speaking minority, observing that it was “...making rapid progress to shifting over to English on a massive scale” (NOTE 4) and affirming the importance of re-establishing instruction in French. Since the 1970s, the revitalization of the status of the French language has occurred in part through the intervention of francophone institutions that reinforce French usage in the province. This institutionalization, while offering a space for the French language in the public arena, has also been accompanied by heightened reinforcement of a standardized variety of French.

Descriptive Linguistic Studies

Before the mid-20th century, there was not a single study—even a fragmentary one—on the state of spoken French in Manitoba. In 1954, a short article by J. B. Sanders described certain aspects of the process of language shifting that occurs when two languages are in close contact and speakers are compelled to adapt to new social environments. He pointed out such details as a diminishing field of job opportunities in the minority language and a growing domination of English in specific semantic fields, such as farming or automotive language. This article, however, conveyed a traditionalistic ideology that called for a linguistic conservatism purported to be vital to conserving the “purity” of the language while decrying the “contamination” brought about by language contact (NOTE 5).

More in-depth linguistic research would not be forthcoming until the mid-1970s, which saw publication of an article by Clyde Thogmartin (NOTE 6). The results of his research would subsequently be referred to regularly by linguists interested in varieties of French spoken in the Canadian West. He focused on the distinctive phonological attributes of three varieties of French spoken in Manitoba—namely, varieties with European, Canadian and Métis roots. The study of linguistic traces left by European varieties of French remains largely undeveloped. Certain aesthetic assessments discernible in epilinguistic remarks made by French-speaking Manitobans and gathered by linguists show that the French spoken in the Saint Claude region continued well into the 1990s to be perceived as a distinct and highly regarded variety of French—with interviewees referring to the “lovely accent” (NOTE 7) found in this region. Anne-Sophie Marchand has noted, especially among older speakers, some surviving phonetic and lexical characteristics passed down from patois or regional varieties of French spoken in France. An example of this is pochon, which refers to a ladle (une louche in standard French) in the patois spoken in the Jura region of France (NOTE 8). In the absence of a more methodical linguistic description of the current state of these European varieties, we may legitimately wonder if these assessments are not made on the basis of stereotypical perceptions, if these vestiges of European varieties of French are not likely to fade away with the next generation, or if there are indeed significant linguistic particularities that endure to this day.

French Rooted in Quebec

Manitoba French shares a significant number of linguistic attributes with Quebec’s French. This can be explained by their shared roots. These attributes are found at all levels of language. It is without a doubt the relative intensity of the contact with English that has been and continues to be the primary factor differentiating these two varieties of French. In Manitoba, the more dominant presence of English in society is the source of the code switching (regular back-and-forth switching from one language to the other), borrowings and calques that characterize all situations of close contact between two languages. Some examples: “... and then, tu voulais-tu encore venir à Subway avec moi ?” “I can’t remember if it was dix-huit heures ou dix-neuf heures.” “Les batteries sont dead, anyway .” The French spoken in Manitoba has also evolved independently in its own way and, even in an urban setting, it shows some attributes that may have disappeared from urban usage in Quebec, or that have different frequencies of use in the two provinces. Manitoba French benefits, moreover, from Quebec’s active involvement in matters of terminology and translation, and Quebecois coinages (clavardage, courriel, hameçonnage, webmestre) are often adopted and assimilated into widespread use.

Describing Diversity

The matter of variation of usage in different French-speaking areas and the need for objective descriptions of these usages that also acknowledge the existence of a plurality of standards continue to attract the attention of linguists interested in the French-speaking world of today (NOTE 9). In the particular case of Manitoba, it is important to carry on with research on the present-day varieties of French that subsist in the province in order to gain a better understanding of the specific characteristics of these varieties and to contribute to the preservation of a linguistic heritage that has been passed down over several generations.

Sandrine Hallion Bres

Associate professor at Saint

Boniface College (Collège universitaire

de Saint-Boniface)

Co-investigator on the research project Identités

francophones de l'Ouest canadien (Francophone Identities in the Canadian

West)

NOTES

1. http://www.unesco.org/fr/languages-and-multilingualism/historical-background/

3. Dulong, Gaston, L’état actuel du français au Manitoba, Université Laval, 1963, Archives of the Collège Universitaire de Saint-Boniface, Fonds collection générale (General Collection), P013/002/019, 16 p.

4. Op. cit., p. 5.

5. Sanders, J.B., “St. Claude, French Citadel in Western Canada,” Revue canadienne de linguistique, 1.1, 1954, pp. 9–12.

6. Thogmartin, Clyde O., “The Phonology of Three Varieties of French in Manitoba,” Orbis, 23, 2, 1974, pp. 335–349. Since this time, research by Robert Papen, Liliane Rodriguez, Anne-Sophie Marchand and Sandrine Hallion Bres has enriched the body of knowledge on varieties of French in Manitoba; however, the combined research of these individuals does not constitute an exhaustive description.

7. Marchand, Anne-Sophie, “L’identité franco-manitobaine : de l’identité métisse au métissage des identités ,” Thèmes canadiens/Canadian Issues, vol. XX, 1998, p. 14.

8. Op. cit., p. 15.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Amprimoz, Alexandre L. et Antoine Gaborieau, « Les parlers franco-manitobains », dans L'état de la recherche et de la vie française dans l'ouest canadien, Winnipeg, Actes du premier colloque du cefco (1981), 1982, pp. 99-109.

Dulong, Gaston, L’état actuel du français au Manitoba, Université Laval, mai et juin 1963, ACUSB, Fonds collection générale, P013/002/019, 16 p.

Hallion, Sandrine, Étude du français parlé au Manitoba, thèse de doctorat, Université de Provence, Aix-en-Provence, 3 tomes, inédite, 2000, 464 p. + 859 p. (corpus).

Marchand, Anne-Sophie, « La francophonie plurielle au Manitoba », Francophonie d’Amérique, n° 17, printemps 2004, pp. 147-159.

Marchand, Anne-Sophie, « L’identité franco-manitobaine : de l’identité métisse au métissage des identités », Thèmes canadiens/Canadian Issues, vol. XX, 1998, pp. 57-72 .

Painchaud, Robert, Un rêve français dans le peuplement de la Prairie, Saint-Boniface, Éditions des Plaines, 1987, 303 p.

Papen, Robert A., « La diversité des parlers de l’Ouest canadien : mythe ou réalité ? », Cahiers franco-canadiens de l’Ouest, vol. 16, n° 1-2, 2004, pp. 13-52.

Rodriguez, Liliane, La langue française au Manitoba (Canada), Histoire et évolution lexicométrique, Tübingen, Niemeyer, Canadiana Romanica, 2006, 519 p.

Sanders, J.B., ”St. Claude, French citadel in Western Canada”, Revue canadienne de linguistique, 1.1, 1954, pp. 9-12.

Thogmartin, Clyde o., ”The Phonology of Three Varieties of French in Manitoba”, Orbis, 23, 2, 1974, pp. 335-349.

Additional DocumentsSome documents require an additional plugin to be consulted

Images

-

Annonce publicitaire

Annonce publicitaire

pour des terres... -

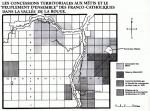

Carte de Réal Bérar

Carte de Réal Bérar

d intitulée « ... -

Carte montrant les mu

Carte montrant les mu

nicipalités bil... -

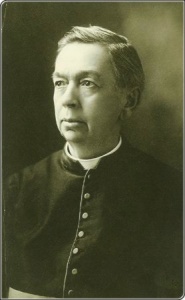

Charles-Agapit Beaudr

Charles-Agapit Beaudr

y, prêtre-colo...

-

Couverture de l'ouvra

Couverture de l'ouvra

ge de Jacquelin... -

Entrefilet paru en pa

Entrefilet paru en pa

ge couverture d... -

Entrefilet paru en pa

Entrefilet paru en pa

ge couverture d... -

La chanteuse d'origin

La chanteuse d'origin

e franco-manito...

-

La quartier francais

La quartier francais

de Saint Bonifa... -

Le drapeau franco-man

Le drapeau franco-man

itobain -

Le personnel du burea

Le personnel du burea

u d’immigration... -

Logo de la Société

Logo de la Société

franco-manitoba...

-

Ouvrage Le Nord-ouest

Ouvrage Le Nord-ouest

: la province ... -

Page couverture d'un

Page couverture d'un

guide pour l'é... -

Page couverture du Co

Page couverture du Co

lonisateur cana... -

Photo d'enfants assis

Photo d'enfants assis

sur un char lo...

-

Photo d'un groupe d'h

Photo d'un groupe d'h

ommes suisses d... -

Photographie du cénot

Photographie du cénot

aphe (Piroiton)... -

Population du Manitob

Population du Manitob

a selon la lang... -

Retour de la messe de

Retour de la messe de

minuit au Mani...

Hyperliens

- La colonisation francophone au Manitoba 1870-1914

- Histoire du Manitoba français

- Dossier de Radio-Canada sur la culture française au Manitoba : «La culture française, so what?»