The Habitation at Port-Royal, Acadia

par LeBlanc, Ronnie-Gilles

Situated near the little town of Annapolis Royal in Nova Scotia, Port-Royal National Historic Site of Canada brings to life the French colony founded in 1605 by Pierre Dugua de Mons and his companions, including the famed Samuel de Champlain and the no less illustrious Jean de Biencourt de Poutrincourt et de Saint-Just. Visitors arriving at the site by Route 1 along the Annapolis Basin could easily mistake the fortified complex for the original construction, built in the early 17th century. In fact, the old buildings reminiscent of another time are actually a historical reconstruction dating from the late 1930s, the first of its kind in Canada.

Article disponible en français : Habitation de Port-Royal en Acadie

A Site Rich in History

The Habitation is part of Port-Royal National Historic Site of Canada, a 19 hectare site situated on the shores of the Annapolis Basin, just opposite Goat Island. Part of the site was ceded to the Canadian government by the government of Nova Scotia in 1938 with a view to building a replica of the Port-Royal Habitation on its presumed original location, based on the plan drawn by Samuel de Champlain some 300 years earlier. The Habitation and its vegetable garden are surrounded by woods stretching north to the heights of North Mountain, bordering the Bay of Fundy. In 1923, four years after the founding of the Historical Sites and Monuments Board of Canada, the Board had recommended that a plaque be erected to commemorate the historic site. However, several groups of history enthusiasts wanted to do more. After fifteen years of lobbying and efforts on their part, the government of Canada began reconstruction work on the Habitation, which was completed in 1939.

The Port-Royal Habitation is a replica of one of the oldest European settlements on the North American continent. Between 1605 and 1613, numerous French colonists lived here, forging close ties with the local Mi’kmaq First Nation, an alliance with France that would endure for a century and a half. It was at Port-Royal that the first play in North America was performed, The Theatre of Neptune, written by Marc Lescarbot. The reconstruction of the Habitation was also the first heritage initiative of its kind in Canada.

The Beginnings of the Habitation at Port-Royal

It was during their exploratory voyage in 1604 in search of a suitable site for a colony that de Mons and his companions first entered the basin that Champlain would name Port-Royal. Struck by the beauty of the surroundings and the potential for settlement, Poutrincourt convinced Sieur de Mons to give him a grant to the land. The following summer, near a stream, the first buildings were erected in a rectangle around an interior courtyard, a fortified farm configuration common at the time. The first winter was difficult, but with the fresh meat provided by the neighbouring Mi’kmaq, only 12 colonists died of scurvy. The following winter proved even less deadly thanks to the Order of Good Cheer created by Champlain: members of the Order took turns finding game and preparing sumptuous meals for their compatriots. In 1605, the settlers began clearing land around the Habitation and on the present-day site of Annapolis Royal in order to plant grain and vegetables, which yielded good harvests. Poutrincourt even built a mill on Allain’s Creek for the grain.

A Strategic Hub for the Development of the Region

In addition to Sieur de Mons, Poutrincourt and Champlain, other well-known figures of New France spent time at Port-Royal, including Marc Lescarbot, François Gravé du Pont and Louis Hébert, who went on to become one of the first settlers in Quebec. The chief of the Mi’kmaq nation, Membertou, also played a vital role. Without the help of the chief and his people, the European colonists would never have been able to establish themselves and survive on North American soil. In fact, it was very much in the interest of the French to forge friendly ties with the First Nations. And when the Port-Royal settlers were called back to France in 1607, they left the Habitation under Membertou’s guard.

Poutrincourt, who had in the meantime been appointed lieutenant governor of Acadia and granted fur trading privileges and fishing rights for Port-Royal, recruited new settlers. They included his own son, Charles de Biencourt de Saint-Just; Claude Turgis de Saint-Étienne de La Tour and his son Charles (who would later play an important role in the development of Acadia); Father Jessé Fléché, a Recollet priest; the apothecary Louis Hébert; Thomas Robin, Vicomte de Coulogne, who helped finance the expedition; and some 20 tradesmen.

In 1610, Poutrincourt and his companions returned to the Habitation, which had been maintained in tip-top condition by Chief Membertou and his people. To prove to the court that he took his religious responsibilities seriously, Poutrincourt had Membertou and 20 members of his family baptized by Father Fléché, then asked his son, Charles de Biencourt, to return to France with Thomas Robin to notify the court of the conversions. There they were ordered to take several Jesuits back to Acadia with them to pursue the evangelization efforts begun by Father Fléché. The expedition, composed of fathers Pierre Biard and Énemond Massé and some 30 men, arrived in Port-Royal in the spring of 1611.

The French initiatives in this part of Acadia were undermined, however, by internal tensions and English attacks led by Samuel Argall. In the fall of 1613, English forces destroyed what remained of the Sainte-Croix Island settlement, then pillaged and burned the Port-Royal Habitation, effectively sealing the fate of the colony founded by de Mons some eight years earlier.

In the spring of 1614, Poutrincourt returned for the last time to Acadia to find the colony in ruins. Biencourt, the La Tours and a group of settlers decided to stay on to ensure a French presence in the region. They remained there until 1632, when England recognized France’s claim to Acadia under the Treaty of Saint-Germain-en-Laye. In the interval, a Scottish colony had been founded in 1629 on the present-day site of Annapolis Royal, the very place where French settlers had sowed grain crops some 20 years earlier. The colony was taken over in 1632 by the French, who turned it into the administrative capital of Acadia, and by the same token, the cradle of the Acadian people.

Commemorative Efforts

After 1613, the site of the original Port-Royal Habitation was largely forgotten, apart from occasional references to the ruins of the settlement on French and English maps published a century after its destruction. Over 300 years went by before steps were taken to commemorate this key site in the history of the young Canadian nation. In 1924, the Historic Sites and Monuments Board of Canada declared the founding of Port-Royal an event of national historic importance and unveiled a plaque near the location identified by William Francis Ganong in 1911 as the probable site of the Habitation. Shortly afterward, the idea of rebuilding the colonial outpost was born.

It was an American, Harriette Taber Richardson, who provided the impetus for this bold historic initiative, a symbolic gesture championed by the descendants of the English settlers of New England and Virginia who had destroyed Port-Royal three centuries earlier. Taber Richardson, who spent her summers in the Annapolis Royal area, forged ties with the local community, notably the Historical Association of Annapolis Royal. A fundraising campaign launched by the Associates of Port-Royal in the late 1920s—before the impact of the Crash of 1929 had truly been felt—brought in the tidy sum of $10,000, which was earmarked for reconstruction of the Habitation. In the meantime, the Historical Association of Annapolis Royal pledged to acquire the presumed site of the original settlement.

In Ottawa, however, government officials did not share the same enthusiasm, and for most of the following decade, the project progressed at a snail’s pace. Both the National Historic Sites and Monuments Board of Canada and the Canadian Parks Service questioned the wisdom of reconstructing the Habitation. Fortunately, restoration projects undertaken in the mid-1930s in Ontario (at Fort York in Toronto and Fort Henry in Kingston) and in the United States (Williamsburg) proved that historic enhancement projects helped create jobs and develop infrastructure for the fast-growing tourism industry. In 1938, the Canadian government finally recognized the value of the project and incorporated the reconstruction of the Port-Royal Habitation into a job creation program aimed at countering the effects of the Depression in the region.

In conjunction with the Historical Association of Annapolis Royal and the province of Nova Scotia, the federal government purchased the property where the Habitation was presumed to have stood. Archaeological excavations and reconstruction work got underway in fall 1938. The project marked a turning point in the history of the Canadian Parks Service, which had never been involved in a private land purchase before, let alone any historic reconstruction work.

A Forgotten Site Brought Back to Life

In 1938, Charles W. Jeffreys, a Canadian artist specialized in the visual recreation of historical events from the nation’s past, began to conduct research, notably on early 17th century French architecture. Inspired by the writings of Champlain and Lescarbot, among others, and the plan of the Habitation drafted by Champlain himself, he drew up architectural blueprints for the reconstruction. Jeffreys also produced illustrations showing the daily life of French settlers at the Habitation in the early 17th century.

The reconstruction effort sought to reconcile old and new, both in terms of the materials used and the construction techniques employed. Local tradesmen still familiar with traditional techniques in brickmaking, joinery, carpentry and masonry were brought in. Interestingly, the number of workers hired was the same as the number of men who built the original Habitation in 1605. Once the buildings were complete, they needed to be furnished. Again, the job went to C.W. Jeffreys, who was able to identify historic objects like clothing, tools and furniture. His involvement in the reconstruction project clearly contributed to its success by enhancing its historical credibility. Along with the objects reproduced according to Jeffrey’s instructions, the French government agreed in the 1960s to provide a number of authentic period objects that were used to furnish and decorate the forge, kitchen, bakery and chapel.

From the moment Port-Royal officially opened in the summer of 1941, efforts were made to provide historic interpretation of the site. Even before reconstruction work began, steps were taken to recreate the garden Champlain had established during his time at Port-Royal. Seeds were obtained from France, along with vines from New England. The Canadian government also decided to acquire the neighbouring properties and demolish the buildings there in order to recreate the Habitation’s historic landscape. Since the 1980s, park interpreters have worked hard to recreate the daily life of the French settlers at the colony of Port-Royal.

The Historical Reconstruction Phenomenon, a Heritage in Itself

When this ambitious historic reconstruction project was undertaken in the late 1930s, it was a first for the Canadian government. Given the limited knowledge available at the time, notably in the areas of historical and archaeological research, the project provided an opportunity to learn more about period construction techniques. Attention to detail and to historical accuracy considerably enhanced the project’s credibility.

For the Canadian heritage conservation movement, the reconstruction marked the start of a new phase in which the government agreed to play a greater role by getting directly involved in historical property acquisition and in funding ventures of this type. Moreover, the reconstruction of the Habitation at Port-Royal was the result of a collective effort on the part of the community and various levels of government, both within Canada and internationally. In 1995, the Historic Sites and Monuments Board of Canada went so far as to recognize the historic reconstruction as being of national historical significance, both as the first project of its kind in the country and as an important milestone for the Canadian heritage conservation movement. As a result, Port-Royal National Historic Site of Canada maintains its intrinsic value, while also providing visitors with an educational glimpse into the site’s history.

Ronnie-Gilles

LeBlanc

Parks Canada

NOTES

1. Without the assistance of the First Nations, the French settlers would have had a tough time surviving in their new surroundings. They quickly adopted certain types of aboriginal clothing and means of transportation, including snowshoes, the toboggan and the canoe, which eased their adaptation to the North American environment. As for the First Nations, they got their first taste of the Christian faith and also adopted certain technologies introduced by the Europeans, notably metal weapons and tools like the axe and the copper pot that completely transformed their traditional way of life.

2. However, de Mons chose instead to establish an agricultural settlement at Sainte-Croix Island, which proved to be a mistake. Nearly half the colonists—35 out of 79—died of scurvy during the winter of 1604–1605. When spring arrived, de Mons and his companions left the island, dismantling their buildings and bringing them to Port-Royal.

3. It is worth noting that the Huguenot merchants financing this new expedition refused to let the Jesuits embark unless the funds they had put up were reimbursed. Madame de Guercheville, a devout and highly influential lady of the court, did some court fundraising of her own and raised enough money to pay off the Huguenots in exchange for a partnership between Biencourt, Thomas Robin and the Jesuits.

4. During the 1960s, certain repairs became necessary on the 20-year-old buildings at the site. Archaeologists brought in during the course of the work had the opportunity to reassess the discoveries made at the site in the late 1930s. Their investigation revealed that most of the artifacts recovered during reconstruction of the Habitation were from a later occupation of the site. In other words, the true location of the Habitation has yet to be found. This is not necessarily a bad thing, because it means that the 1605 site was not disturbed during the original reconstruction work.

Additional DocumentsSome documents require an additional plugin to be consulted

Images

-

Abitasion [sic] ou ha

Abitasion [sic] ou ha

bitation de Por... -

Chantier pour la reco

Chantier pour la reco

nstitution de l... -

Chantier pour la reco

Chantier pour la reco

nstitution de l... -

Chantier pour la reco

Chantier pour la reco

nstitution de l...

-

L'habitation en 1940

L'habitation en 1940

-

L'inauguration en jui

L'inauguration en jui

llet 1941 -

La reconstitution de

La reconstitution de

l'habitation de... -

La reconstitution de

La reconstitution de

l'habitation de...

-

Le chantier de Port-R

Le chantier de Port-R

oyal -

Le chantier pour la r

Le chantier pour la r

econstitution d... -

Le chantier pour la r

Le chantier pour la r

econstitution d... -

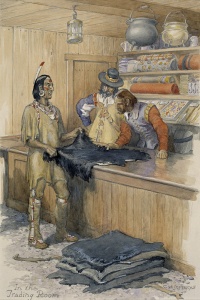

Lescarbot reading his

Lescarbot reading his

play. The Thea...

-

Ouvrier pendant la co

Ouvrier pendant la co

nstruction de l... -

Ouvriers pendant la c

Ouvriers pendant la c

onstruction de ... -

Ouvriers travaillant

Ouvriers travaillant

à la constructi... -

Ouvriers travaillant

Ouvriers travaillant

à la contructio...

![Abitasion [sic] or habitation of Port-Royal, built in 1605](/media/thumbs/5105/300x213-5105_port_royal_planancien.jpg)