Fleming Mill

par Gravel, Denis

The Fleming Mill is located in Stinson Park overlooking Lac Saint-Louis in the Montreal borough of LaSalle. The mill was built out of stone in 1827 and is the only Anglo-Saxon-inspired mill still standing in the Province of Quebec. Since 1982, it has been the emblem of the LaSalle borough. In 1983, the mill was officially recognised as an archaeological heritage site by the Ministère des Affaires Culturelles du Québec. After being restored in 1990, it became a historical interpretation centre. The mill itself is a part of LaSalle's industrial heritage and its history tells the story of Scottish immigration into the area. The mill is thus an integral part of Montreal and an important part of its history.

Article disponible en français : Moulin Fleming

An InterpretationCentre

The Fleming Mill Interpretation centre welcomes several thousand visitors every summer. An interpreter-actor accompanies the visitors along the guided tour. Inside the mill, visitors learn about the typical life of a miller in the 19th century and get a chance to observe artefacts that were discovered on the site in 1989. The building is located on the tourist circuit on the southwest part of the Island of Montreal close tothe Lachine Canal. The mill is a recognisable landmark for cyclists, pedestrians and is even visible from boats on the Saint Lawrence River. Surrounded by trees in Stinson Park (NOTE 1), the mill's interpretation centre is also used for theatre intended for a school-aged audience.

A One-of-a-Kind Mill in Quebec

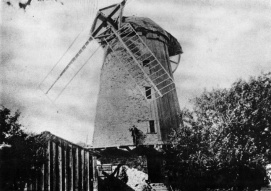

The mill is located on a bank overlooking Boulevard LaSalle. This majestic structure is both the largest mill on the island of Montreal and the only Anglo-Saxon-inspired mill in the Province of Quebec. The mill is built of fieldstone and has a truncated-cone-shaped tower capped with a cone-shaped roof. Its architectural features confirm its Scottish origins. In order to protect it from north-easterly winds, the masonry on that side of the structure is covered with wooden panels. Visitors to the site can also get a glimpse of the mill's machinery. The exterior mechanism, which enabled the miller to point the blades in the direction of the wind, was rebuilt for the benefit of visitors. From the gallery the miller could pull a cable linked to a wind vane, in order to pivot the roof and blades towards the wind. Today, the system can no longer be used because the interior mechanism no longer exists (NOTE 2).

The Fleming Mill Case: an Attack on the Seigneurial System

In 1814, the Scotsman William Fleming bought a plot of land located in Bas-Lachine, facing Lac Saint-Louis. This was close to the chemin du Roi (NOTE 3) (present-day Boulevard LaSalle), which was major thorough fare and transportation route at the time. The following year, he built a wooden windmill on his property. This building was in direct conflict with the Seigneurial banalité rights of the Séminaire de Saint-Sulpice de Montréal (referred to as the Montreal Seminary hereafter) (NOTE 4). In fact, at that time, the Seminary had had a monopoly on all flour-producing mills since 1663. On the 28th June, 1816, the Seminary insisting on its Seigneurial [feodal] rights, ordered that the mill be demolished (NOTE 5). Fleming's lawyers replied that the Seminary had no legal power to rule in Canada. Their status was given by the Séminaire de Saint-Sulpice de Paris, which had no authority in Canada. Later in 1816, the legislative council raised its doubts as to the legitimacy of the Montreal Seminary's claims. The Seminary replied shortly thereafter, publishing a treatise entitled "Consultation de Douze des Plus Célèbres Avocats de Paris" [Notes from Consultations with 12 of Paris's Most Renowned Lawyers] (NOTE6). The document argued that the Saint-Sulpician community did have such legal rights under the British regime and that the Montreal Seminary was independent of its Parisian counterpart.

In 1822, the King's Bench ruled in favour of the Seminary stating precedents that established the Seminary's power. They thus ordered non-regulation mills to be demolished (NOTE 7). Unsatisfied, Fleming appealed the decision. Three years later, the eight judges of the Court of Appeal were unable to reach a majority decision (NOTE 8). This stalemate constituted a victory for Fleming, since, in the absence of a decision, the Montreal Seminary could not force him to demolish his mill. William Fleming subsequently took advantage of the victory to rebuild the mill in stone in 1827(NOTE 9).

The slowness of legal proceedings (which could often take ten years) encouraged other citizens to express their discontent with the feudal rule of the Catholic Church. Between 1816 and 1840, around forty individuals expressed their grievances in a variety of ways. Fleming, however, was the only person to take his claim to court (NOTE 10). At the time, the Seminary's power was heavily contested by the upper-class English-speaking community. A Royal decree issued in 1840 finally recognised the legal status of the Montreal Seminary (NOTE 11). At this time, there was a struggle between the two different legal systems used in the colony: the first had been inherited from the French regime and the second took its inspiration from British law. In this context, the Fleming Mill found itself in the middle of a battle for the abolition of the Seigneurial System and the establishment of a free market.

The Enduring Tenacity of a Threatened Building

From its very beginning, the Fleming Mill had an uncertain future because of the conflict between Fleming and the Montreal Seminary. In 1827, Fleming signed a building contract with the mason, William Morrison to build the stone windmill that stands to this very day. From 1827 to the 1880s the ownership and operation of the mill remained within the Fleming family.

Despite the rise of industrial mills during the 19th century, the Fleming Mill stayed active for occasional use by those who enjoyed traditional methods. When William Fleming died in 1860, his son John took over operation of the mill. When activities ceased in the 1880s, the mill's condition rapidly deteriorated. In 1892, the mill lost two of its blades andthe rotating mechanism collapsed. At the turn of the century, the roof and the mechanism had fallen inside the building (NOTE 12). After John Fleming's death, his widowed wife, Isabella Wylie bequeathed the property to Reverend Martin Callaghan. Subsequently, Callaghan transferred the property to Reverend E.P. Curtin. Then in 1914, Curtin made it a donation to the religious community known as the Presentation Brothers of Ireland. During the first quarter of the 20th century the mill was somewhat neglected since its owners had little interest in conserving it or restoring it.

In 1928, The Wellcome Foundation (Burroughs Wellcome) acquired the mill and the surrounding land from the Presentation Brothers of Ireland with the intention of establishing a pharmaceutical company in the area. Around 1930, the mill and its internal mechanism were restored. Atthat time, the mortar between the stones was weathered. In addition to the rusted condition of the internal mechanism, the millstone and the roof had all fallen to the ground. As a result of the company's efforts, the mill was saved from total destruction. However, at that time no further work to restore the mill was planned.

In 1947, the City of LaSalle acquired the site from Burroughs Wellcome. At that time, the city was undergoing vast expansion. From 1949 to 1971, LaSalle's population went from 9,000 to 71,000 inhabitants .During this period municipal authorities were more concerned about residential and industrial development than about heritage protection. Along boulevard LaSalle, many old houses were demolished to make room for more modern buildings. Among the notable houses destroyed was that of the miller who ran Montreal Seminary's watermill. The house, which was probably built in the 18th century by the Saint-Sulpice Seminary, was located next to the Lachine rapids. In April of 1971, it was used in a training exercise by the local fire department despite protests by many residents.

In 1976, the Cavelier-de-LaSalle Historical Society convinced the city to apply to the Ministère des Affaires Culturelles du Québec, in order to have the mill recognised an official heritage site. They felt that their application was justified even if the millstones and the interior mechanism had disappeared without a trace. In 1982, the city of LaSalle adopted the mill as its official emblem and continued to put pressure on the Quebec government to accelerate the processing of the heritage recognition application. In the process, the city was also trying to improve its own public image, which had been tarnished when it demolished the Ogilvie Manor. Designed by Alexander C. Hutchison, the manor had belonged to William Watson Ogilvie, a mill owner who died in 1900. The destruction of the Ogilvie Manor in 1981, which had served as a clubhouse for the old LaSalle golf club, infuriated the population. Residents responded by voting out the mayor, Gerald Raymond, in the 1983 municipal elections. The city somewhat regained its reputation on the 13th of January, 1983, when the Fleming Mill was recognised as an official archaeological heritage site by the Ministère des Affaires Culturelles du Québec.

Restoringand Developing the Mill as a Heritage Site

When the reconstruction work began, the, goal was to only protect the building from weather. However, in 1989, the City of LaSalle decided it not only wanted to protect the structure, but it also wanted to promote the site as a public attraction. And effectively, this is just what the political party in power, Action Civique, promised their electorate. Accordingly, the mayor Michel Leduc signed an agreement with the Ministère de la Culture that granted official permission to the researchers to start archaeological digs and historical research, in order to better understand the mill's history and origins.

The goal of the restoration project was not to return the mill to its fully functional state, but to give it a new role in the community. The mill would serve as a reminder of 19th century Montreal and the tumultuous circumstances during which the mill was built. The main challenge facing authorities was to adapt the building to modern uses. Restoration work intended to bring mill's external appearance back to its former glory (particularly the stonework) was carried out using methods and criteria commonly used in the conservation of architectural heritage. Old photographs and drawings were used to reproduce the original style and dimensions. However, the inside of the mill underwent more modern renovations since no records existed that described how it used to look. This was also necessary in order to accommodate future visitors.

The municipal and provincial authorities intended to create an interpretation centre that would put the mill's history on display. However, the mill ended up being given a much larger role. It became an Interpretation Centre for the history of LaSalle. Because of its proximity to bike and pedestrian paths, main routes and the Saint Lawrence River, it also became a tourist attraction. Furthermore, it became popular for educational field trips school-age children. The Fleming Mill's new status was finally confirmed, when the interpretation centre was inaugurated on the 7th of July, 1991.

In 1991, the city of LaSalle commissioned Quebec author and biographer Georges-Hébert Germain to write a book about the mill titled "Moulin Fleming, un Moulin pas Banal" [The Fleming Mill; Not Your Ordinary/Seigneurial Mill] (NOTE 13). His book tells the story of William Fleming and his family and his famous court case-making mill.

In 2003, the Montreal borough of LaSalle did an archaeological inventory of the Fleming Mill, in order to better understand how buildings were constructed between 1815 and 1875. This process was intended to continue the work carried out between 1989 and 1991, whose objective was to locate the miller's house, forge, shed and other outbuildings (NOTE 14).

In 2005, investments made the City of Montreal and the Ministère des Affaires Municipales made it possible to construct an out-door theatre right next to the mill. The theatre is a public place where people, especially youth, can be educated abou tthe need for heritage conservation in an entertaining manner.

The site of the Fleming Mill Interpretation Centre is a popular attraction during the summer, particularly on weekends. There are guided tours and live entertainment or people can come just to relax in the park'sgreen space. It is difficult to determine just how popular the mill is, simply on the basis of the number of visitors. However, it was never the intention of municipal authorities to make it a spot to attract large crowds. The size of the building only has a capacity for about twenty visitors at a time. Today, the interpretation centre is mostly a stop for educational field trips. Nevertheless, the Fleming Mill continues to be a landmark for all residents of LaSalle and Montreal and for whom ever else might be curious to learn more about the site.

Denis Gravel

Historian

Cavelier-de-LaSalle Historical Society

NOTES

Note 1. Name of a former municipal councillor, Albert Wesley Stinson, whose wife, Leta Greydon Stinson, was one of the founders of the Cavelier-de-LaSalle Historical Society in LaSalle. Denis Gravel and Viviane Bouchard, LaSalle Then and Now, Montréal, Cavelier-de-LaSalle Historical Society, 1999, p. 217.

Note 2. For a more detailed description of the Fleming Mill's features, see Denis Gravel, Moulins et meuniers du Bas-Lachine, 1667-1890, Sillery, Les Éditions du Septentrion, 1995, p. 88 à 92. See the summary available on the City of Montreal's website [page visited on the 10th November, 2009]: patrimoine.ville.montreal.qc.ca/inventaire/fiche_bat.php?arrondissement=0&batiment=oui&lignes=2&id_bat=9231-25-2681-01&debut=245

Note 3. Former name: le chemin du Bas-Lachine [Lower Lachine Road], today boulevard LaSalle.

Note 4. Also known as Messieurs les ecclésiastiques du Séminairede Saint-Sulpice de Montréal : les Sulpiciens.

Note 5. Denis Gravel, Monographie du moulin Fleming à Ville de LaSalle, LaSalle, Société historique Cavelier-de-LaSalle, 1990, p. 23 à 28. Chapter 3 (III) gives an account of the legal battle between the miller and the Séminaire de Montréal.

Note 6. Denis Gravel, Monographie du moulin Fleming à Ville de LaSalle, LaSalle, Société historique Cavelier-de-LaSalle, 1990, p. 25.

Note 7. Brian Young, In its Corporate Capacity, The seminary of Montreal as a Business Institution, 1816-1876, Montréal, McGill-Queen's University Press, 1986, page 42. In 1774, court appeals obliged censitaires [tenants] to bring their grain to the Seigneurial mill [in order to be able to levy the banalités (tithes levied fora seigneurial lord)] and required that all free (banalité exempt) mills to be demolished.

Note 8. It was a split decision: four in favour of Fleming, four against.

Note 9. BAnQ, minutier Peter Lukinfils, 13 juillet 1827, Agreement settled between William Fleming and the mason William Morrison.

Note 10. Brian Young, In its Corporate Capacity, The seminary of Montreal as a Business Institution, 1816-1876, Montréal, McGill-Queen's University Press, 1986, p. 177-181.

Note 11. The court order confirmed the Seminary's property rights, but also included the censitaire's [tenant's] commutation [exchange or transfer] rights, which enabled him (upon request), to sunder his concession plot from the seigneurial system and the responsibilities that were associated with it. Commutation is a form of feudal indemnity [e.g. banalité] that was to be paid to the Seminaire de Montréal. The amount of the indemnities due was based on the value of the tenant's land. Thereafter (the ruling) each individual could decide what he wanted to do with his land assets, inaccordance with the law enforced by the government. Paul-Yvan Marquis (Me), La tenure seigneuriale dans la province de Québec, Chambre des notaires du Québec, 1987, p. 134-144; Brian Young, Inits Corporate Capacity, The Seminary of Montreal as a Business Institution, 1816-1876, Montréal, McGill-Queen's University Press, 1986, p. 114-115.

Note 12. Groupe de recherche en histoire du Québec, Le potentiel archéologique du site du moulin Fleming, Ville de LaSalle/ ministère des Affaires culturelles, November 1989, p. 19.

Note 13. This text takes its inspiration from the Monographie du moulin Fleming à Ville de LaSalle by the Historian Denis Gravel, as is indicated on the title page of his book. [Translators note: the term banal is used in a word play. Here the French banal can mean: "not your ordinary run-of-the mill" OR "not a Seigneurial mill"]

Note 14. Le moulin Fleming. Inventaire archéologique du parc Stinson et du site du moulin Fleming, BiFj-7, Montréal, 2003. SACL inc. En 1989 et en 1991, This is the Groupe de recherche en histoire du Québec [History Research Group] which does the archaeological surveys.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Dionne, Pierre-Yves, La technologie traditionnelle du moulin à vent du Québec, mécanisme et fonctionnement, Thèse (M. A.), Université Laval, 1984, 108 p.

Germain, Georges-Hébert, Moulin Fleming. Un moulin pas banal, LaSalle, Ville de LaSalle/ministère des Affaires culturelles, 1991, 70 p.

Gravel, Denis, Monographie du moulin Fleming à Ville de LaSalle, LaSalle, Société historique Cavelier-de-LaSalle, décembre 1989, 92 p.

Gravel, Denis, Moulins et meuniers du Bas-Lachine, 1667-1890, Sillery, Les Éditions du Septentrion, 1995, 122 p.

Gravel, Denis et Viviane Bouchard, LaSalle Then and Now, LaSalle, Cavelier-de-LaSalle Historical Society, 1999, 256 p.

Groupe de recherche en histoire duQuébec, Le potentiel archéologique du site du moulin Fleming, Villede LaSalle/ministère des Affaires culturelles, novembre 1989, 70 p.

Groupe de recherche en histoire du Québec, Sondages exploratoires et surveillance archéologique sur le site du moulin Fleming, Ville de LaSalle/ministère des Affaires culturelles, 1991.

Pinard, Guy, Montréal, son histoire, son architecture, T. 2, Montréal, La Presse, 1988.

SACL inc., Le moulin Fleming. Inventaire archéologique du parc Stinson et du site du moulin Fleming, BiFj-7,Montréal, Ville de Montréal, 2003, 72 p.

Young, Brian, In it sCorporate Capacity, The seminary of Montreal as a Business Institution, 1816-1876, Kingston/Montréal, McGill-Queen's University Press, 1986, 295p.

Additional DocumentsSome documents require an additional plugin to be consulted

Images

-

Le moulin Fleming apr

Le moulin Fleming apr

ès sa restaurat... -

Le moulin Fleming ava

Le moulin Fleming ava

nt sa restaurat... -

Un comédien-guide à l

Un comédien-guide à l

'entrée du moul...

Hyperliens

- Old windmill on the Lachine Road, near Montreal, QC, about 1910

- On the Lower Lachine Road, Lasalle, near Montreal, QC, about 1865

- Fleming Mill, circa 1905