Blacksmith’s Trade in the Province of Quebec

par Tremblay, Robert

In recent years, there has been a veritable renaissance in the traditional blacksmith's trade, especially with regard to art metal work, decorative wrought iron and the restoration of historic buildings. Some interpretation centres even offer visitors and neighbouring communities a range of useful products made to order by artisan blacksmiths. It is impossible to fully appreciate the re-emergence of these almost forgotten practices without first understanding the long and storied history of blacksmithing in Quebec, which was marked by a continuous evolution of trade practices and techniques that started back in the days of New France. It is also important to point out the resilience of the blacksmiths despite the many threats to their trade: harsh working conditions, fickle economic cycles, the dawn of industrial mass production after 1850 and the advent of the automobile in the early 20thcentury.

Article disponible en français : Métier de forgeron au Québec

The Birth and "Canadianization" of the Trade in the 17th and 18th Centuries

In 1627, in order to encourage trades people to emigrate to New France, King Louis 13th decreed that French artisans which had practiced their trade overseas for more than six years would be allowed to set up shop as master craftsmen in Paris or any other city in the kingdom, should they decide to return to the mother country. His initiative succeeded in attracting a number of unlicensed locksmiths, gunsmiths, nailmakers, toolmakers, knife makers and farriers to the colony's cities and villages. (NOTE 1) However, a lack of organisation to protect their respective areas of competence, combined with difficulty in finding work year-round, forced many of these metal workers to change occupations. By the end of the 17thcentury, a number of them had decided to practice agriculture along with their original profession, while others had already left the trade to become carpenters, stonemasons, traders or coureur des bois [voyageurs]. (NOTE 2) Though the iron-working trades did not disappear completely, most of them did merge throughout the 18th century, giving rise to a "jack of all trades" variety of blacksmith, who shoed horses and made tools, nails, wheels and the occasional cart or carriage. The creation of the Forges du Saint-Maurice in the 1730s, led to the birth of a new category of "heavy-duty" blacksmiths (hammersmiths, stokers and goujats [workers responsible for shaving imperfections from iron as it was forged]), but their work had nothing to do with that of rural smiths; rather, they refined the raw iron that came out of blast furnaces. Canadian blacksmiths, born out of the French artisan tradition, practiced a semi-skilled trade based on both first-hand knowledge acquired over the years and advances brought about by the latest scientific and technological developments. (NOTE 3)

Despite the variety of services offered by blacksmiths, their location sometimes elevated certain tasks above others. In certain environments, such as seigneurial fiefdoms, the fabrication of hand tools (felling axes, adzes, planes, etc.) and farm implements (ploughs, harrows, etc.) was very important. Elsewhere, in fortified cities such as Quebec or in remote trading posts, smiths spent a great deal more time fashioning rifles and pieces of artillery. Work in fishing villages, on the other hand, mainly involved making hooks, anchors and ironwork for boats. However, horseshoeing came to occupy more and more of blacksmiths' time as more horses were brought to the colony, mainly for transportation, but also for manual labour.

Once a blacksmith's workshop was established within a community, it of course became a place where customers could acquire any iron object they might need, but it was also a place where young apprentices hoping to one day become master craftsmen could learn the trade. Since the flow of immigrants from France was constantly disturbed by the many armed conflicts that plagued the colony, such apprenticeships played a key role in providing manpower for workshops and in "Canadianizing" the trade.

The rise of the British regime brought a number of English, Scottish and Irish blacksmiths to the colony. These artisans, as well as those that came to Canada following the American Revolution (1776-1783), made important contributions to the technical heritage of local blacksmiths. Because of England's technical superiority in metal processing, which was due in large part to the crucible and puddling methods, blacksmiths in Quebec soon had access to a much more malleable iron that helped improve the quality of their products. (NOTE 4)

A Changing Trade, A Disputed Monopoly

However, the future did not hold the same fate for all. While the early 19th century was the dawn of a new era of expansion for country blacksmiths in Lower Canada (Quebec), the same was not true for blacksmiths in urban centres, who were simply unable to meet the growing demand for iron products brought on by a new trade economy characterised by the growth of transit trade with Upper Canada (Ontario) and the development of steamships. These short falls were aggravated by three outside factors: the importation of iron products from Britain and Sweden, the rise of smaller forges flooding local markets withcast-iron products (stoves, ploughs, steamship engines, etc.) and finally, there-emergence of traditional specialised trades (toolmakers, nail makers, wheelwrights, etc.). As a result, the work of blacksmiths in cities was reduced to what was once but part of their responsibilities: horseshoeing and fixing tools. At the same time, the number of forges in the cities reached a plateau. In Montreal, for example, the number of forges peaked at about 30 in 1830, then began its steady decline in 1850. (NOTE 5)

Adapting to a New Industrial Reality in the Second Half of the 19th Century

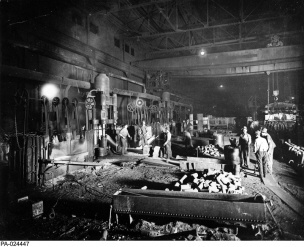

Finding few opportunities to practice their trade in the city, many young smiths took jobs in industrial foundries making steam engines or in industrial manufacturing plants created after 1850 to supply major railroad companies. Specialised workshops for casting iron parts soon cropped up alongside existing casting, boiler making and finishing shops.

Throughout the 19th century, a number of machine tools-forge hammers, dimpling machines, shearers, etc. began appearing in workshops, instantly changing the smiths' traditional routines. However, given the imperfect and rudimentary nature of the first machine tools, which resulted in a product that needed to be tweaked and perfected by an experienced worker, many smiths managed to maintain a great deal of professional independence within the factories. Nonetheless, because of rapid advances in mechanisation and the improvement of the original prototypes in the 1880s, some of the blacksmiths' skills were put to the test against competition from new industrial tradesmen such as machinists. (NOTE 6)

The Impact of the Automotive Age

For country blacksmiths, who had already suffered for decades from the availability of cheaper hardware items (nails, locks, tools, vehicle springs, etc.) in urban areas, the advent of the automobile in the early 20th century was a crushing blow, this time to the final vestiges of their trade: horseshoeing. In fact, the account ledgers of blacksmiths in rural areas show a clear decline in profit from 1910 onward. (NOTE 7) A number of Quebec blacksmiths thus decided to leave their hometowns for newly settled areas of Western Canada, where chances of succeeding at their trade were higher. Others went to work in WWI munitions factories. For some, however, the best option was to transform their old smithies into workshops for repairing automobiles and farm equipment. While their knowledge of iron certainly helped with making the transition, they still needed to learn basic repair techniques and familiarise themselves with new equipment, such as pneumatic tools and acetylene welding torches, which were introduced in the 1920s.

As automobiles slowly replaced horses, many former blacksmiths in the city were also forced into non-traditional activities. Some managed to pull through by turning to niche markets such as machining dies or manufacturing aircraft components. (NOTE 8) Another, larger group survived thanks to the decorative iron craze that swept urban high society in the 1930s and 1940s. Inspired by the art nouveau movement, cities such as Montreal and Quebec launched urban development projects (parks, squares, promenades, gardens, etc.) that featured extensive use of wrought iron, typically in the form of lampposts, fountains, gates, fences and balustrades. This allowed a small group of metalworkers, such as Montreal's Arthur Faustin and Quebec City's Philibert Marchand, to live comfortably off their art. (NOTE 9)However, new industrial techniques for bending iron sounded the death knell for this small-scale artisanal production as early as the 1950s. (NOTE 10)

The final remnants of a long tradition of striking and shaping iron in Quebec gradually disappeared in the latter half of the 20th century. Arthur Tremblay's forge in Les Éboulements, the last in a town that once had four, closed in 1978. Four years later, the forge owned by Montreal's Cadieux brothers, who specialised in elevator parts, another vestige of an artisanal tradition, also closed for good. (NOTE 11) Only a handful of workshops were fortunate enough to be recognised as historic monuments by the Ministère des Affaires Culturelles, leaving the rest to fade into oblivion. Since the work was no longer being done, the transfer of knowledge was interrupted, thus threatening the techniques and methods that characterised the blacksmith's trade in Quebec for over 300 years.

At a time of globalisation and the reorganisation of the Canadian iron and steel industry around giants such as Arcelor-Mittal, a new generation of trades people is attempting to revive local traditional ironwork practices in the name of cultural diversity and heritage conservation. The 1995 opening of the Musée de la Forge Cauchon in La Malbaie, on the site of a forge that folded 32 years prior, is a perfect example of this trend. (NOTE 12) Similar projects to save traditional forges with the help of local communities have also been spearheaded on the Gaspé coast, in Rock Island (Stanstead county) and in Drummondville. Even more promising for the future of the trade was the re-emergence in the 1990s of a dynamic core of practitioners looking to breathe new life into the old techniques and use them to restore historic buildings and create art, as evidenced by the work of Guy Bel of Île d'Orléans. This new generation of blacksmiths is currently part of the Confrérie des Forgerons du Québec [Quebec blacksmiths guild], which is already 25 members strong. (NOTE 13)

RobertTremblay

Historian, Canadian Science and Technology Museum

NOTES

Note 1. J. Lacoursière, "De quelques métiers sous le Régime français", in C. Simard(dir.), Des métiers ... de la tradition à la création : anthologie en faveur d'un patrimoine qui gagne sa vie, Sainte-Foy, Éditions GID, 2003, p.60.

Note 2.J.-C. Dupont, "Forge au Canada français", L'Encyclopédie du Canada, Montreal, Éditions Alain Stanké, 1987, p. 768.

Note 3.Dupont, loc. cit., p. 768.

Note 4. C.K. Hyde, Technological Change and the British Iron Industry, 1700-1870, Princeton, Princeton University Press, 1977, pp. 83-84.

Note 5. R.Tremblay, Du forgeron au machiniste : l'impact social de la mécanisation des opérations d'usinage dans l'industrie de la métallurgie à Montréal, de 1815 à 1860, Ph.D thesis, Montreal, Université du Québec à Montréal, 1992, pp. 57-60.

Note 6. In 1891, blacksmiths only represented an estimated 41% of steel and ironworkers inCanada, whereas the figure had been 69% forty years earlier. See: W. Wylie,"Une matière nébuleuse : description de l'emploi dans le secteur du fer et de l'acier d'après les rapports des recensements imprimés de l'Amérique du Nord britannique, 1851-1891," Rapport de recherche # 199, Ottawa, Parks Canada, 1983, p.7.

Note 7.J.-C. Dupont, L'artisan forgeron, Sainte-Foy, Presses de l'Université Laval, 1979, pp.187-188.

Note 8. C. Fournel and J. Drolet, Profil sectoriel : l'industrie québécoise de la forge, Quebec, Ministère de l'industrie et du commerce, 1986, pp.23-25.

Note 9. Canada Trade Index, 1930, 1936, 1940.

Note 10. C. Simard, Artisanat québécois: technique, qualité, conservation, 3 vol., Montreal, Éditions de l'homme, 1975-1977, vol 2 : p.185.

Note 11. F. Dubé and B. Genest, Arthur Tremblay, forgeron de village, Quebec, Ministère des affaires culturelles, 1978, pp. 11-12; and Montreal Gazette, June 11th, 1982. The author would like to thank Mr. Larry McNallyfor providing precious information on the Cadieux forge.

Note 12. "La Forge-Menuiserie Cauchon", http://www.forgecauchon.ca, page viewed29/02/08.

Note 13. "La Confrérie des forgerons du Québec", http://www.forgerons.qc.ca, pagevisited 29/04/08.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Bealer, Alex W. The Art of Blacksmithing, New York, Harper & Row, 1984, 487 p.

Bérubé, André et al., Le forgeron de campagne : un inventaire d'outils, Ottawa, National Museums of Canada, 1975, 67 p.

Bradley-Smith,H. R., Blacksmiths' and Farriers' Tools at Shelburne Museum, Shelburne, Vt., Shelburne Museum Inc., 1966, 272 p.

Dupont, Jean-Claude, L'artisan forgeron, Sainte-Foy, Les Presses de l'Université Laval, 1979, 355 p.

Fournel, Carol and Jacques Drolet, Profil sectoriel : l'industrie québécoise de la forge, Quebec, Ministère de l'industrie et du commerce, 1986, 75 p.

Hardy, Jean-Pierre, Le forgeron et le ferblantier, Montreal, Boréal Express, 1978, 126 p.

Hardy, Jean-Pierre et David-Thiery Ruddel, Les apprentis artisans à Québec, 1660-1815, Montréal, Les Presses de l'Université du Québec, 1977, 220p.

Hyde, Charles K., Technological Change and the British Iron Industry, 1700-1870, Princeton, Princeton University Press, 1977, 283 p.

Lacoursière, Jacques, "De quelques métiers sous le Régime français," in Cyril Simard (dir.), Des métiers ... de la tradition à la création : anthologie en faveur d'un patrimoine qui gagne sa vie, Sainte-Foy, Éditions GID, 2003, pp.58-63.

Ruddell, David-Thiery et Robert Tremblay, By Hammer and Hand, all Acts Do Stand:Blacksmithing in Canada before 1950, Ottawa, Canadian Science and Technology Museum, ‘Transformation' Collection, #18, 2010, 80 p.

Tremblay, François, "Artisans du Québec," in Cyril Simard (dir.), Des métiers ... de la tradition à la création : anthologie en faveur d'un patrimoine qui gagne sa vie, Sainte-Foy, Éditions GID, 2003, pp.72-85.

Tremblay, Robert, Du forgeron au machiniste: l'impact social de la mécanisation des opérations d'usinage dans l'industrie de la métallurgie à Montréal, de 1815 à1860, Ph.D thesis, Montreal, Université du Québec à Montréal, 1992, 383 p.

Tremblay, Robert, Histoire des outils manuels au Canada, de 1820 à 1960 :héritage européen, techniques de fabrication et entreprises manufacturières, Ottawa, Canadian Science and Technology Museum, ‘Transformation' Collection, #10, 2001, 105 p.

Wylie, William, The Blacksmith in Upper Canada, 1784-1850: A Study of Technology, Culture and Power, Gananoque, Ont., Langdale Press, 1990, 216 p.

Wylie, William, Une matière nébuleuse : description de l'emploi dans le secteur du fer et de l'acier d'après les rapports des recensements imprimés de l'Amérique du Nord britannique, 1851-1891, Parks Canada, Research report #199, Ottawa, 1983, 17 p.

FILMOGRAPHY

Léo Plamondon, "Émile Asselin, forgeron" (1974). Ministère des Communications (Québec), Centre de documentation en civilisation traditionnelle. Content: Émile Asselin, a blacksmith from Saint-François, l'Île d'Orléans, speaks about his trade and shows how to shoe a horse and fabricate a variety of objects (axes, cold chisels, hooks, etc.). A copy is available at Université Laval's Cinémathèque.

Additional DocumentsSome documents require an additional plugin to be consulted

Images

-

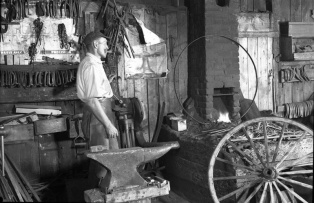

Atelier de forge de l

Atelier de forge de l

a Canadian Car ... -

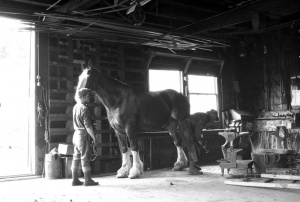

Extraction d’un fer à

Extraction d’un fer à

cheval par un ... -

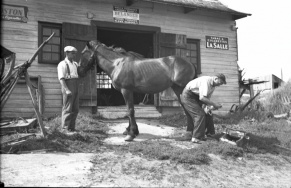

Ferrage d’un cheval d

Ferrage d’un cheval d

e labour canadi... -

Forgeron de Saint-Fid

Forgeron de Saint-Fid

èle, Québec, co...

-

Jeune recrue apprenan

Jeune recrue apprenan

t l’art de la s... -

Machiniste et son ass

Machiniste et son ass

istant procédan... -

Marteau-pilon à vapeu

Marteau-pilon à vapeu

r inventé en 18... -

Modèle de forge porta

Modèle de forge porta

tive encore en ...

Document PDF

Hyperliens

- Confrérie des forgerons du Québec

- Forge Cauchon (La Malbaie, Qué.)

- Forum de l’artisanat du métal

- Gaspesian British Heritage Village