Dance of the Unwed Older Sibling

par Pichette, Jean-Pierre

In French-speaking Ontario, especially in the north of the province, a region, which has been settled for a little more than a century, there is a flourishing wedding tradition that is intended to "punish" the happy couple's unmarried older siblings. Of all the names that have been associated with the tradition over the years and in the various regions it is practiced, the sock or trough dance are the most common. Interestingly enough, the tradition is practiced throughout French-speaking North America, although it has only recently been the object of study, particularly in outlying areas. Furthermore the custom has been largely forgotten by the cultures from which it originated, namely in France, which brought the tradition to the New World.

Article disponible en français : Danse de l’aîné célibataire

A Form of Social Discipline

There is a fundamental

rule which is found consistently throughout the ages and in a number of

cultures, a rule that boils down to primogeniture, or the rights of the oldest

child. When it comes to marriage, this rule means that the oldest child must

marry before his or her younger siblings(NOTE

1). Statistics in French Canada show a similar trend.

(NOTE

2) When someone deviates from the norm, it is up to

family or village leaders to intervene. Such deviations are more than a matter

of individual choice; they are a sort of public offense that upsets the balance

of the entire community. There was a time when the community would simply delay

the younger sibling's marriage, but nowadays offenders must atone for their

crime by carrying out a particular ritual, a sort of amende honorable through which their socially unacceptable actions

are publicly exposed, condemned and temporarily forgiven.

A "punishment" is also incurred for the infraction and the best time for the

customary sentence to be carried out is during the wedding. Sometimes the

"punishment" is handed down on the eve of the ceremony, but it is most commonly

done on the younger sibling's wedding day. In Canada, the sentence has taken on

many forms, but it is almost always a dance.

The Sock Dance in French-Speaking Ontario

There is a tradition among the French-speaking population of North-eastern Ontario that punishes older brothers or sisters that have been beaten to the altar by a younger sibling. The ritual is carried out on the younger sibling's wedding day, usually during the dance that follows the meal. At a specified time, the older sibling is called to the centre of the room and asked to remove his or her shoes and pull up his or her pant legs. The younger sibling or another member of the immediate family then dresses the offender in a pair of multicoloured knee-high socks--in which red is usually a dominant colour--that were made specifically for the event by another family member. The socks are often also decorated with bells, pompoms, ribbons, feathers and similar items designed specifically to make them as garish and ridiculous as possible.

The older sibling then gets up and dances alone to a piece of music with a strong beat, ideally a reel. The display can go on for ten minutes or more, during which time the guests surround the dancer, cheering, teasing and sometimes throwing money and change. Other guests sometimes join in for a few steps, and sometimes they take turns getting the dancer to spin in place, making them dizzy. At the end of the ritual, which is all in good fun, the money on the floor--which can range from tens to a few hundred dollars-- is collected and given to the newlyweds. The older sibling takes off the socks and keeps them as a souvenir.

If there is more than one older sibling, they dance together and it is possible that the same individual wil end up dancing at several weddings-there are stories of one confirmed bachelor dancing seven times before getting married! While the custom is not actually mandatory, it is often seen as such. Refusing to participate could result in mockery, practical jokes or some other form of "punishment."

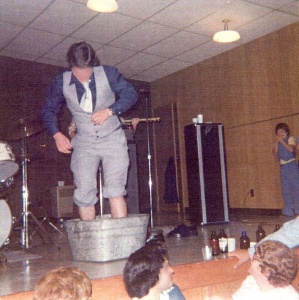

The Trough Dance

Though the tradition of the sock dance seems to flourish throughout French-speaking Ontario, in the past, it has taken on more humiliating incarnations that today are disappearing fast. One of these variations-the trough dance-is still common. It appears to be the only form of the tradition found in South-western Ontario, namely in Pointe-aux-Roches(NOTE 3). The objective is still to discipline an unmarried older sibling on the day of a younger sibling's wedding by making them dance, but in this case, the victim dances in a pig trough (in the past, it was a wash basin). This more rural tradition has evolved slightly in recent years: whereas dirty old troughs were once used for the dance, today's offenders are now made to dance in a clean trough made or purchased just for the occasion. In nearby Grande-Pointe, the ritual was carried out as recently as 1988.

From the Trough to the Washbasin

However, the trough dance and the different variations on the tradition seem most common in the Sudbury area. In the 1950s, according to a witness from Saint-Charles, the dance was done barefoot on an upside-down bench. Another claims that in the 1940s and 1950s, the dance was done in a trough or washbasin or in one's stocking feet on an overturned bench and that no money was thrown. The account is confirmed by another witness describing the tradition's evolution in her own family: "My grandparents learned about the tradition when one of my great-uncles got married before his older brother in the ‘40s or ‘50s. My mother remembers one of her brothers dancing in a pig trough in the 1960s. Before that time, people in Saint-Charles didn't dance in their socks, but rather in a pig trough or a wash basin filled with water. My father did that in 1972 or 1973. The sock dance started in '77 or '78."(NOTE 4)

The Trough Dance in

Acadia

In his study of popular Acadian traditions, ethnologist Jean-Claude Dupont

provides what appears to be the earliest known description of the trough dance

in New Brunswick. He writes that "in Cocogne, Richibouctou, Moncton, Memramcook

and Shédiac, a musician would play a tune and the spinster had to dance in the

pig trough, which had been brought inside for the event. When it was a bachelor

that was being punished for not marrying, he would be made to eat out of the

same trough." Dupont adds that "in recent years, the ladies have been made to

dance around the trough rather than in it, and they are given a bottle of wine

at the end."(NOTE

5) A survey recently conducted in South-eastern New

Brunswick confirmed that the tradition now involves dancing around a trough

filled with alcohol--a mixture of beer and hard liquor--that the dancer must

drink.(NOTE

6)

Other Goals of the Ritual

The tradition was conceived with a number of goals in mind and although its real purpose is to temporarily reset the balance that was upset by the older sibling's inappropriate conduct, it has a number of secondary benefits as well. For the wedding guests, it is an entertaining event, one that is sometimes planned even in the absence of any real offense. For the victim, it is a way of announcing that he or she is available to marry. Finally, it serves as another welcome source of financial assistance for the newlyweds. In the latter case, it replaces other traditions, such as stealing the bride's shoe to pass around for donations or dancing with the bride and pinning money to her dress. Although the economic aspect of the tradition is limited to Northern Ontario, that may have helped it to spread.

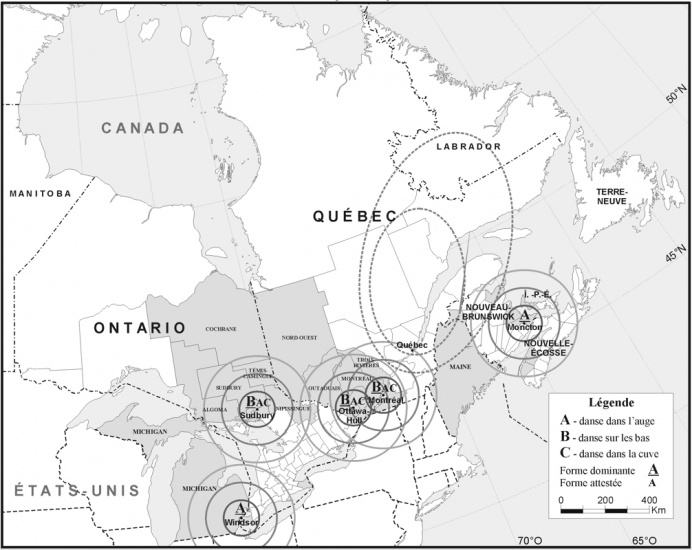

Distribution Across Canada and North America

Recent surveys and studies provide a clearer image of the spread of this tradition across a large part of French-speaking North America. It is an exercise that enables researchers determine the vitality of the custom. The practice is common in northern Ontario, the Abitibi-Temiscamingue region, the Outaouais region in Eastern Ontario and Western Quebec and the Richelieu River Valley. It is also found in South-western Ontario, Acadia (New Brunswick), the North-eastern United States and Louisiana. Similar traditions in which the trough is used are found elsewhere in Western Canada, New Brunswick, Quebec, Prince Edward Island and Louisiana. However, the ritualized dance is completely unknown in several parts of Quebec, such as the Quebec City region, the Saguenay-Lac-Saint-Jean region, the Lower St. Lawrence, the Gaspé and the Eastern Townships. Its popularity is also declining in Trois-Rivières and Montreal.(NOTE 7) While these statistics for the custom's decline or absence are very significant, what is most striking is that the tradition is alive and well in Quebec's outlying regions, as well as among French-speaking minorities across North America.(NOTE 8)

The Sock Dance in Papineau's Day

A letter(NOTE 9) from Joseph Papineau to his brother Denis-Benjamin in Montreal dated January 10th, 1826 contains the earliest known reference to the sock dance in Canada. Regarding his brother André's recent proposal, Papineau notes that it would be difficult for his brother to marry the younger Eugénie before her older sister Adélaïde was married, since the elder sister "would have to dance in her stocking feet." The soon-to-be-newlyweds decided to postpone their marriage by a few weeks in order to avoid interfering with Adélaïde's rights as the first-born daughter. Papineau concludes by promising to go to La Petite Nation and make Adélaïde "dance a reel in her stocking feet" if she did not marry. The letter, which attests to the authority of the tradition, suggests that it was already well established within the Papineau family and that the two brothers had witnessed it regularly throughout their youth (between 1765 and 1775). If the tradition dates as far back as the habitants of New France, then its origins can surely be traced back to the motherland.

European Origins

One thing is certain: the two forms of "punishing" the elder unmarried sibling (dancing in one's sock feet and dancing in a trough) did not originate in Canada. Similar traditions have been recorded in France and French-speaking European countries and even on the British Isles(NOTE 10) and yet the tradition is only found in the French-speaking parts of North America, although the Canadian traditions most closely resemble customs found in Great Britain.(NOTE 11) The search for the missing link should not be limited to Canadians of British (English, Scottish, Irish or Welsh) descent, among whom the tradition is all but absent, but rather should focus on continental Celtic populations, in particular the Bretons, whose ties to both French and Celtic culture could explain the mystery of a tradition that could have only been passed along with French settlers.(NOTE 12)

A Resurgent Tradition

The dance of the unwed older sibling, which exists today with varying frequency in almost every corner of the North American melting pot, continues to thrive in a world that claims to shy away from tradition. In a time when family units are often smaller, fractured and sometimes reconstituted; and in a day when marriage itself isn't necessarily a given, it is surprising that such a tradition has survived. What is even more surprising is the most recent form taken on by the resurging tradition: older brothers and sisters with common-law partners are being forced to dance at the weddings of their younger siblings, be they civil or religious ceremonies. There are even stories of the mother of one of the newlyweds, who was herself not legally married, being subjected to the "punishment." Finally, the spread of the custom throughout Western Quebec and especially in Northern Ontario is proof of a resurgent--not declining--tradition. It is also evidence that outlying regions often cling more tightly to traditions-and such traditions play an important role in preserving cultural heritage.

Jean-Pierre Pichette

Université Sainte-Anne

NOTES

Note 1. Edward Westermarck, Histoire du mariage, translated by Arnold Van Gennep, 3rd edition, Paris, Mercure de France, 1935, volume II, p. 111-112.

Note 2. Gérard Bouchard, Quelques Arpents d'Amérique. Population, économie, famille au Saguenay 1838-1971, [Montreal], Boréal, [1996], p. 201.

Note 3. Personal account by Mr. Paul Tremblay, May 7th, 2001; his account confirms that the ritual was carried out in February of 2001.

Note 4. Personal account by Mélanie Roy, a student in the folklore and ethnology program at the University of Sudbury, 1999.

Note 5. Jean-Claude Dupont, Héritage d'Acadie, Montreal, Leméac, "Connaissance," 1977, p. 231-232.

Note 6. Antonine Maillet alludes to the custom in her novel Pélagie-la-Charrette (English version available: Pélagie: Return to Acadie), placing it two centuries earlier, in 1776: "A girl who's past her twentieth birthday and hasn't yet married could be made to eat from the trough; it's tradition." ([Montreal], Leméac, 1979, p. 236; translated by Philip Stratford, Fredericton, Goose Lane Editions, 2004). The same author explained the tradition in an earlier work: "To make someone eat from the trough: to assert one's dominance over them (especially in matters of love)" (Antonine Maillet et Rita Scalabrini, L'Acadie pour quasiment rien. Guide historique, touristique et humoristique d'Acadie,

Note 7. Note that some regions have yet to be studied.

Note 8. The fading cultural customs of central or originating regions, as compared to the outlying, sometimes isolated regions' farther-reaching shared cultural memories are the origin of the "principe du limaçon," [snail principle], which is explained in an upcoming article ("Le principe du Llimaçon ou la résistance des marges. Essai d'interprétation de la dynamique des traditions," Cahiers Charlevoix. Études franco-ontariennes no. 8)). This principle gave rise to an international seminar titled La Résistance des marges - Exploration, transfert et revitalisation des traditions populaires des francophonies d'Europe et d'Amérique (Port Acadie, no 13-14-15, 2009).

Note 9. Item no. 787 Papineau-Bourassa Collection, which can be found in the Archives nationales du Québec. See "Correspondance de Joseph Papineau (1793-1840)," in Antoine Roy, Rapport de l'archiviste de la province de Québec [RAPQ] pour 1951-1952 et 1952-1953, [Quebec], Secrétariat de la Province, Rédempti Paradis, [1953], vol. 32-33, p. 227-228.

Note 10. Arnold Van Gennep, Manuel de folklore français contemporain, Paris, Éditions A. et J. Picard, tome I, vol. 2 Du berceau à la tombe (fin). Mariage - Funérailles, 1946, p. 628-635. Martine Segalen, who "combined the information contained in the writings of folklorists and personal accounts in order to study marriage folklore in the late 19th century and today," says nothing about the tradition. See Martine Segalen, Nuptialité et alliance. Le choix du conjoint dans une commune de l'Eure, Paris, G.-P. Maisonneuve et Larose, « Mémoires d'anthropologie française », 1972, p. 111-120 ; the subject is also absent from her most recent book: Éloge du mariage, [Paris], Découvertes Gallimard, "Culture et société," [2003], 128 p.

Note 11. The earliest known reference is found in act 2, scene 1, lines 31-34 of The Taming of the Shrew, written by William Shakespeare (1564-1616) in 1594.

Note 12. Jean-Pierre Pichette, "De la Mégère apprivoisée au Roman de Julie Papineau. Origines d'un rituel du mariage franco-ontarien," Cahiers Charlevoix. Études franco-ontariennes no. 6, Sudbury, Société Charlevoix and Prise de parole, 2004, p. 224-233.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Dupont, Jean-Claude, Héritage d'Acadie, Montreal, Leméac, "Connaissance," 1977, p. 231-232.

Pichette, Jean-Pierre, "Danser sur ses bas. Réminence d'une sanction populaire dans le rituel du mariage franco-ontarien," Cahiers Charlevoix. Études franco-ontariennes, no. 5, Sudbury, Société Charlevoix and Prise de parole, 2002, p. 229-311.

Pichette, Jean-Pierre, "De la Mégère apprivoisée au Roman de Julie Papineau. Origines d'un rituel du mariage franco-ontarien," Cahiers Charlevoix. Études franco-ontariennes no. 6, Sudbury, Société Charlevoix and Prise de parole, 2004, p. 195-248.

Pichette, Jean-Pierre, "Le Principe du limaçon ou la résistance des marges. Essai d'interprétation de la dynamique des traditions," Cahiers Charlevoix. Études franco-ontariennes no. 8, Ottawa, Société Charlevoix and University of Ottawa Press, 2010, [59 p. ms. not yet released].

Pichette, Jean-Pierre [editor], La Résistance des marges - Exploration, transfert et revitalisation des traditions populaires des francophonies d'Europe et d'Amérique - Proceedings of an international symposium held from August 15 to 18 at Université Sainte-Anne, in Port Acadie - Revue interdisciplinaire en études acadiennes, no. 13-14-15, spring 2008, fall 2008, spring 2009, Université Sainte-Anne, 478 p.

Van Gennep, Arnold, Manuel de folklore français contemporain, Paris, Éditions A. et J. Picard, tome I, vol. 2 Du berceau à la tombe (fin). Mariage - Funérailles, 1946, p. 628-635.

Ward, Peter, Courtship, Love and Marriage in Nineteenth-Century English Canada. Montréal & Kingston, London, Buffalo, McGill-Queen's University Press, [1990], 219 p.

Additional DocumentsSome documents require an additional plugin to be consulted

Images

-

L’enfilade des bas. A

L’enfilade des bas. A

vant la danse, ... -

La danse dans une aug

La danse dans une aug

e à Pointe-aux-... -

La danse dans une bai

La danse dans une bai

lle à Pubnico, ... -

La danse dans une cuv

La danse dans une cuv

e à Saint-Charl...

-

La danse de l’aîné. L

La danse de l’aîné. L

a mariée encour... -

La danse de l’aînée c

La danse de l’aînée c

élibataire en O... -

La danse en semelles

La danse en semelles

de bas à Ottawa... -

La récolte de la monn

La récolte de la monn

aie. La mariée ...