A Bit of French North America Takes Root at Versailles

par Dassié, Véronique

The Versailles Palace Park receives nearly 10 million visitors each year and, since 1979, has been registered on the UNESCO World Heritage List. In 1999, a devastating storm hit Versailles, and in its aftermath many French, Canadian and Quebec citizens rose to the occasion and demonstrated their attachment to this heritage site by planting their emblematic trees there. The restoration of this "place of shared memory" provided an opportunity to initiate research in order to take a fresh look at the history of the location. The results of the research revealed the complexity of the site's heritage appropriation history. Due to these latest developments, the relations the governments of Canada and Quebec maintained with the French government took on fresh new meaning. In addition, the regular tree re-planting activities organized after the storm demonstrated the increased scope and importance of the findings as they related to the various cultural identities involved.

Article disponible en français : Amérique française enracinée à Versailles

Trees as a Shared Heritage Asset

The Versailles Palace Park currently covers 800 hectares, including 300 hectares of forest and a number of gardens. The so-called "classical" garden or Petit Parc [Small Park], located behind the palace and the Grand Parc surrounding the Trianons, serve to delineate the two main sectors.

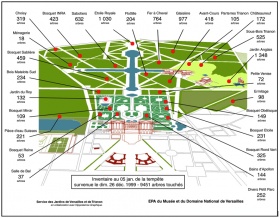

The devastation of the park during the 1999 storm (over 9,000 trees were affected) triggered an unprecedented concern for the site's heritage vale. Extensive media coverage of the event and the setting up of an international fund-raising campaign led to the mobilization of the public on a global scale. The damages incurred provided an opportunity to replant a great many trees, particularly in the Grand Parc sector where the winds did the most damage.(NOTE 1)

Private donations poured in from every corner of the world and a number of countries expressed their solidarity with the restoration project, adding their support to the various private initiatives. As a result of this international interest, the park, particularly the Jardin du Roi [King's Garden] -which is a wooded area located in the Little Park- it became a preferred location for receiving foreign political dignitaries on official visit to France. For example, in 2000, Milos Kuzwart (the Czech minister of the environment), Rudolf Schuster (the president of the Slovak Republic) and Rafic Hahiri (the prime minister of Lebanon) were welcomed in the garden during their official state visits. Representatives of the Quebec and Canadian governments also visited the gardens to offer their so-called ‘symbolic' plantings.

The Gardens of Versailles

Until the 17th century,the trees of the royal holdings were considered valuable only because they made up the forests that were home to the game required for royal hunting expeditions. However the Sun King's [Louis the 14th] colonial policy would change their status once and for all.

In 1663, Louis the 14th ordered his steward to create a park around his Palace at Versailles. At the same time, he established New France as a colony and set up a royal government in the New World, which was under the supervision of his most important minister, Jean-Baptiste Colbert. It was at this point that New France acquired the status of a French province. The administration of these new territories led to an increase in the shipbuilders' need for wood and to the establishment of an official forestry policy, which was also administered by Colbert. As a result of this policy, trees were no longer considered solely as immediately usable resources (for purposes of hunting or heating), but also as assets-in-the-making from which future generations could also benefit.(NOTE 2) This notion was particularly pertinent in the field of shipbuilding, as century-old trees were required in order to build ship masts. Rationalized production gave the trees added heritage value, since the shipbuilding process would thereafter be determined by the renewability of a limited collective asset that could be transmitted from generation to generation.

Nowadays the Petit Parc - the "French-style" garden designed by Charles Brun and André le Nôtre in the 17th century - is still the first garden that visitors see when they arrive at the Versailles Palace. Its most striking features is the orderly formal layout of the garden's symmetrical wooded groves, which are a perfect example of the French classical style. The Petit Parc is home to ornamental lakes and an exceptional collection of lead and bronze statues. Its current heritage value is partially based on site's lavish artistic features, which explains why so many were touched by its devastation following the 1999 storm. Moreover, the influence that the colonial context had upon its creation make it rather understandable as to why it received so much attention (particularly on the other side of the Atlantic).(NOTE 3)

From the Classical to the Picturesque: the King's Garden

The classical garden evolved throughout the reign of the Sun King in conjunction with the project to drain of the swamp surrounding the palace. For example, two new wooded areas were planted south of the Allée Royale (Royal Lane) between 1670 and 1674. Separated by the Allée de Saturne [Saturn Lane], they were landscaped around two ornamental lakes: Île Royale [Royal Island Water] (NOTE 4) and Miroir [Mirror Water]. The fact that the king's gardener's had succeeded in making "fresh water flow in what was once a swamp"(NOTE 5) was deemed to be symbolic of perfect mastery over nature and was yet another demonstration of the absolute power of Louis the 14th.

Today the classical garden remains, for all intents and purposes, as it was originally laid out by Louis the 14th's gardeners. Nonetheless, after the death of the king, his grandson commissioned a few changes. Certain trees that had become old and unstable had to be replaced; and, furthermore, the garden's impeccable symmetry was no longer in keeping with the latest trends, as the Romantic style had become the rage. As a consequence, Royal Island was gradually allowed to disappear, until Alexandre Dufour, the architect of the Versailles palaces at the dawn of the 19th century, decided to replace it once and for all by a less strictly ordered garden, which is today's King's Garden.

The visitor can still trace the original outline of the former ornamental lake, Île Royale, whether by examining the symmetry of the King's Garden lawn that now replaces it or by looking at its "mirror image," the Mirror basin, which remains unchanged. Nevertheless, majestic trees, planted here and there, do much to erase the memory of the earlier formal layout in favour of a more natural look.

It was in the King's Garden that the "symbolic" plantings took place after the 1999 storm. A wide variety of public figures-politicians on official visits to France, generous patrons and show-business celebrities-all came to plant a tree during ceremonies that were held under the attentive gaze of the media. Twenty-five such plantings took place in the King's Garden between 1999 and 2001.

Along with the emblematic tree contributed by their country, the dignitaries also "planted" a bottle of champagne containing a coin from their country, dated that year. The bottle was sealed with the French royal fleur-de-lys emblem in red-wax, adding a festive touch to the occasion. Representatives from the Government of Canada and the Government of Quebec participated in this sort of ceremonial ritual by planting two trees at Versailles during the year following the storm.

A Royal Garden for Canadian Trees

On June 24, 2000, Prime Minister Jean Chrétien ended an official visit to France with a ceremony in the King's Garden. Guided by the Versailles Park president, Hubert Astier, the Prime Minister made his way to a hole prepared for the planting of a Canadian maple. A chrome-plated spade had already been prepared for his use and all was ready for the ceremony to begin.

In his speech, the Prime Minister expressed his solidarity with France, which had just suffered "considerable human and material losses." He underlined the newly established collaborative relationship between the Canadian and the French forestry departments: "The experience of the Canadian forestry workers and the speed with which they intervened in France have been greatly appreciated. The work to be done is dangerous and requires a great deal of dexterity. Certain forestry workers drew upon the experience that they had acquired during the ice storm that struck Quebec and Ontario in January of 1998."(NOTE 6) The foresters' efficiency, reinforced by having experienced a similar sort of crisis two years earlier, made the Canadian intervention that much more effective. As a follow-up to this joint effort, Mr. Chrétien announced yet another initiative: in the near future, Canadian forestry students would arrive as reinforcements and 2,000 additional maple trees would be jointly offered to the palace by the George and Helen Vari Foundation and the Garden Club of Toronto.

On May 21, 2001, a French-Canadian couple, George and Helen Vari, accompanied by the Canadian ambassador to France, Jacques Roy, kept this promise by presiding over the planting of a new Canadian maple in the King's Garden; meanwhile, not far away, Canadian students, accompanied by their French counterparts, planted a maple grove that was dubbed the "Canadian grove."(NOTE 7)

Meanwhile, on November 7, 2000, a Quebec delegation, headed by Clément Duhaime, Quebec's delegate general in France, also contributed to the endeavour by planting a tree-yet another addition to the new legion of trees foresting the King's Garden.

This political interest reveals just how significant Versailles really is on the world stage. But this time, the international efforts involved intricacies that were not usually a part of the offers of material assistance extended in such instances, particularly since it was overshadowed with overtones of political confrontation. The distinction between "Canadian" and "Quebecker" was powerfully asserted throughout the various official speeches and discussions, all of which revealed the identity issues that concerned each government.

Moulding the Past and the Present to Conform to an Ideal of Common Heritage

The speech given by the Canadian Prime Minister, Jean Chrétien, clearly expressed the intentions of the Canadian state "to pursue and develop exchanges between the two countries in the areas of forestry research and mechanization, as well as the lumber industry."(NOTE 8) Investment in Heritage therefore presupposes an alliance based on a shared experience of forestry management. The fact that both nations possess forests means that they also share certain practices: timber harvesting and forestry management. Nevertheless, the traditional dimension of these practices, and therefore details as to how and where they fit on a historical timeline, were not mentioned in the Prime Minister's speech. And so, as it has already emphasized earlier, only the two nations' recent shared common experience-that of similar natural catastrophes-is acknowledged here.

The discourse of the Quebec delegation significantly differed in this regard from those of the Canadian prime minister. Clément Duhaime also referred to the relationship between Quebec and France, but used a radically different tone, declaring that "this gift is proof that we the people of Quebec have also been touched by the damage caused to Versailles resulting from last December's storm [...] and the reason that we feel the effects of the devastation so deeply is that Versailles, with its palace and parks, is, in a certain way, part of our history and our heritage." Here it is the intimate relationship created by shared suffering due to the devastation of common heritage that is highlighted. This compassion is the result of a long, shared history that goes back to the founding of Quebec. For "although preoccupied with supervising the creation of his gardens, the Sun King did not neglect his duty towards the far off colony of New France, but decided to send his illustrious steward, Jean Talon there, in order to ensure that this French possession in North American would flourish."(NOTE 9) Emotions were stirred to a fever pitch by this reference to history: "recalling that era, I cannot help but be struck by the contrast between the refinement of these royal gardens and the untamed nature that awaited the first French colonists on the other side of the Atlantic. Nevertheless, they held on, through thick and thin, and kept the French language alive and well on North American soil. The yellowbirch that we will plant is a worthy symbol of this tenacity which we have inherited from them," concluded Clément Duhaime.(NOTE 10)

In this discourse, there is a reference to the past with a curiously ironic twist: a well organized French colony in North America was indeed being planned at Versailles, just as the palace grounds landscaping project designed by André Le Nôtre, principal gardener to Louis the 14th, was reaching its peak, but the yellow birch, known as a pioneer tree species, recognised as an official emblem of Quebec since 1993, was planted in the King's Garden on the occasion of the Quebec delegation's visit to Versailles, a garden that did not exist when New France was founded. Nevertheless the site's significanceis in relation to the classical garden, and therefore, in opposition to the idea of untamed nature. The birth of Quebec, like that of the classical garden, was based on the idea of mastering the wilderness with its "sylvan" elements serving as archetypes.(NOTE 11) The Le Nôtre landscaping project at Versailles, which endeavoured to domesticate nature, was a symbolic manifestation of the new political order established in the New World.

Promoting and commemorating the grand era in which French exploration and colonisation flourished serves to root the French-speaking world in common soil. The very tree planted in the year 2000 is "a product of Quebec's natural heritage"(NOTE 12) and it symbolizes just how, in all its French-speaking glory, the Quebec government has succeeded in putting down such distinctive roots on the North American continent. Naturally, the very same French North American colony later became a British possession in 1763, a fact that Clément Duhaime failed to mention in his uniquely Quebec flavoured interpretation of history.

A Heritage with Multiple Meanings

For the Canadian representative, the heritage initiative is legitimized by recent circumstances and is tangibly manifested through economic and technical exchanges. For the Government of Quebec however, it is the common past that empowers them to elicit values and language as the historical cornerstones of Quebec's distinctiveness. The material quality that emerges in first discourse contrasts with symbolic quality of the second in the very same way that the rational confronts the emotional.

The interest of the various governments in the Versailles Palace Park serves to highlight the multiplicity of ways that heritage can be appropriated. Each party feels linked to the place, but it would be difficult to evoke a common experience in this regard. Still, such subtleties are barely perceptible for the visitors who crisscross the park today: the Canadian government's sugar maple and Quebec's yellow birch cohabit as good neighbours along with many other trees that are just discreet about their own natural history.

Véronique Dassié

Postdoctoral Intern at the LAHIC and the ATER at Université de Tours François Rabelais

NOTES

Note 1: At the time, the classical garden, or "Small Park" had already been undergoing restoration since 1990. Given that its trees were younger, they proved to be more resistant.

Note 2: Thierry Mariage, "Du territoire au jardin: le cas de Versailles", in École nationale du patrimoine, Patrimoine culturel et patrimoine naturel, Proceedings of the conference of December 12-13, 1994, Paris: La documentation française, 1988, pp. 161-168.

Note 3: It should be noted that, in addition to the assistance provided by Canada and Quebec, there was also, an important donor from the United States-yet another sign of North American involvement in the protection of Versailles' heritage.

Note 4: Simone Hoog, Le jardin de Versailles, Versailles: Art Lys, 2003, p. 49.

Note 5: Michel Baridon sees the complete mastery over nature, as itis reflected in the creation of the classical garden, as an illustration of the absolutist power established by the Sun King, 1998, Les jardins, Paris: Robert Laffont, p. 713.

Note 6: Jean Chrétien, official speech at the King's Garden, June 24th, 2000. [Original translated into English for this text].

Note 7: It should, however, be noted that the "Canadian grove" is not marked by any sign posting and therefore it is impossible for most visitors to identify it without expert assistance.

Note 8: Jean Chrétien, op. cit.

Note 9: Clément Duhaime, the Quebec's delegate general's speech in Paris, November 7th, 2000. [Original translated into English for this text].

Note 10: Ibid.

Note 11: In French, the terms "savage" and "sylvan" share the same etymological origin.

Note 12: Clément Duhaime, op. cit.

BIBLOGRAPHY

Dassié, Véronique, L'incessante repatrimonialisation des arbres de Versailles : matérialiser l'immatériel, Laval, Presses de l'Université Laval, 2007, pp. 331-328.

Himelfarb, Hélène, « Versailles, fonctions etlégendes », in Pierre Nora (dir.), Les lieux de mémoire, 1,Paris, Gallimard, 1997, pp. 1283-1329.

Hoog, Simone, Le jardin de Versailles, Paris, Art Lys, 2003.

Lablaude, Pierre-André, Les jardins de Versailles, Paris, Scala, 2005.

Le Goff, Jacques (dir.), Patrimoine et passions identitaires, Paris, Fayard, 1998.

Mariage, Thierry « Du territoire au jardin :le cas de Versailles », in École nationale du patrimoine, Patrimoine culturel et patrimoine naturel, Actes du colloque du 12 et 13 décembre 1994, Paris : La documentation française, 1988, pp. 161-168.

Maroteaux, Vincent, Versailles, le roi et son domaine, Paris, Picard, 2000.

Pommier, Édouard, « Versailles, l'image du souverain », in Pierre Nora (dir.), Les lieux de mémoire, 1, Paris, Gallimard, 1997, pp. 1253-1281.

Additional DocumentsSome documents require an additional plugin to be consulted

Images

-

Adoptez un arbre.

Adoptez un arbre.

-

Couverture du catalog

Couverture du catalog

ue de la vente ... -

Page couverture du ma

Page couverture du ma

gazine Le Point... -

Patrimoine: les domma

Patrimoine: les domma

ges sont estimé...

Documents PDF

-

«Décembre 1999, Tempête sur Versailles, Chronique d'une émotion», par Véronique Dassié

«Décembre 1999, Tempête sur Versailles, Chronique d'une émotion», par Véronique Dassié

-

Dossier de presse

Dossier de presse

Hyperliens

- Le bouleau jaune, arbre emblématique du Québec

- La deuxième vie des arbres déracinés

- Description du jardin sur le site du Château de Versailles

- Article de Wikipédia sur les Jardins de Versailles.

- Présentation de l'érable, emblème du Canada, par Patrimoine canadien

- Visite officielle du Premier ministre Jean Chrétien à Versailles, sur le site de l'Ambassade du Canada en France