Baie-Ste-Marie (Nova Scotia) Eudists

par Laliberté, Micheline

In 1890, the Eudists [Congregation of Jesus and Mary] arrived from France to set up an educational institution for Nova Scotian Acadians of Baie Sainte-Marie [St. Mary's Bay]. They also took charge of two parishes in the region. Over the decades that followed (mainly until the 1970s), members of the Congregation would fill the roles of educator, religious community builder, administrator, writer, and even nationalist. Their presence at Point-de-l'Église [Church Point] is an example of a cross-cultural encounter between the French and Acadian communities that left its mark on the region on architectural, cultural, and religious levels. The gradual transition from being a congregation consisting mostly of French priests to one staffed almost entirely with Canadian clergy created a balance between these two cultural factions within the institution. Over the years, the Eudist contribution to the Nova Scotian French-speaking community's heritage has been expressed in a wide variety of ways.

Article disponible en français : Eudistes à baie Sainte-Marie (Nouvelle-Écosse)

The Congregation Puts down Roots

A number of coinciding factors led to the 1890 arrival of the Congregation of Jesus and Mary in Baie Sainte-Marie (in South-western Nova Scotia). Initially, the anti-clerical legislation passed by the French government at the end of the 19th century made life increasingly difficult for France's various religious communities. Eventually, early in 1880, various laws were passed in order to secularise education (NOTE 1), a sector of society in which religious figures traditionally had been heavily involved. At the same time that the various legal measures were being taken to secularise France, on the other side of the Atlantic the search was on for a French-speaking community that would help with setting up an educational institution (NOTE 2) in the Acadian community of Baie Sainte-Marie. As a consequence, the convergence of these two factors would bring the Congregation of Jesus and Mary to the region, marking the beginning of their first permanent settlement in North America.

On 16 September 1890, upon their arrival in Baie Sainte-Marie, the founding Fathers, Gustave Blanche and Aimé Morin, took charge of two parishes. (NOTE 3) Almost immediately, they began to offer courses in the rectory to a group of around 20 students. From this point on, the Eudist Fatherrs [priests] would begin to fill the various social roles that religious congregation members so often did in those times. They would alternately work as religious community builders, educators, and priests-and sometimes even as physicians and pharmacists! Furthermore they served as administrators, writers, journalists, musicians, community builders, and-one must not forget to mention-they also became involved in nationalist causes. Thus, from the outset, the work of the Congregation was exercised in the context of an educational, religious, and cultural mission. Over the years, the Eudist contribution to the Baie Sainte-Marie French-speaking community's heritage has found expression in a wide variety of ways.

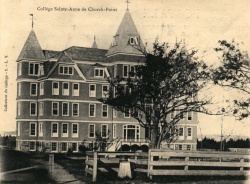

The most visible legacy of the Congregation has been the in area of architecture. Over the course of their century-long presence in the Baie Sainte-Marie region, the priests would regularly fill the role of builders. A good example of this is the construction of the Collège Sainte-Anne, which began the very year the Eudists arrived. (NOTE 4) One of the fundamental missions of the congregation was to train a competent clergy. This led to the building of a juniorate at Point-de-l'Église, which eventually lead to the founding of a seminary in Halifax.(NOTE 5)

In 1899, Collège Sainte-Anne was destroyed by fire. The Congregation decided to rebuild immediately, but this time it was designed and constructed according to slightly different architectural plans. The new building was officially opened during Father Dagnaud's tenure as Superior. While he was in office, Father Dagnaud also supervised the building of Église Mont Caramel [Mount Carmel Church] in the Concessions parish, followed by the reconstruction of the Sainte-Marie parish church along very impressive architectural lines indeed.(NOTE 6) The building would long be known as North America's tallest wooden church. As far as Collège Sainte-Anne was concerned, further wings and additional buildings would gradually be added to the original construction, in response to the growing needs of the institution.

A Unique Cultural Influence

Collège Sainte-Anne represents a meeting-place between France and Acadia on architectural, cultural, as well as religious levels. Upon their arrival, the Eudist Priests were pleased to learn of the Acadians sincere admiration for France and their great respect for the Catholic clergy. Their correspondence with the Superior General Paris and other priests in both France and Canada is replete with similar remarks. Even though from the very earliest years of the congregation it is obvious that-just as it was the case with various the other communities originating in France-the Congregation was a major vehicle in the region for transmitting the cultural values of civilization; communications from the Superior General in France instructed the priests to adopt a prudent, culturally sensitive attitudes in their work on the new continent. They were reminded that, when in Canada, they had to behave like the Canadians. Even though affection for their homeland and ties to the Mother country were considered to be positive affiliations, they were advised to be careful to not raise the ire of the local population, and so they were to promote the Canadian cultural perspective above all else.(NOTE 7)

The name of the institution provides a good illustration of how difficult it has sometimes been over the years to integrate ideas coming from France with those held by the Acadians of South-western Nova Scotia. When the idea of establishing an educational institution at Baie Sainte-Marie was initially being discussed, the various parties involved used the name Mémorial Sigogne [College], in honour of Father Jean Mandé Sigogne, a French missionary who had served in the region for 45 years (1799-1844) and who had made the education of his parishioners his first priority.(NOTE 8) The founding Superior [Sigogne] however very quickly rejected this name and, in honour of a saint highly revered in Brittany, chose Saint Anne instead.

Other examples, especially from the early years, illustrate this combining of traditional French ideas with local ones. The college chapel with its stained-glass windows from Paris and its carpet woven by local Acadian women represents just one such merging of cultures.(NOTE 9) The architecture of St. Mary's parish church is particularly representative of this blending of ideas. According to local tradition, and scholars who have studied the church's history,(NOTE 10) Father Dagnaud's inspiration for the building's design apparently came from the stone church of his home village, Bains-sur-Oust, near Redon in Brittany.(NOTE 11) The Acadians, however, were generally unfamiliar with techniques of building with stone, and so, as lumber was an abundant resource in the region, wood was chosen for the construction.

This Franco-Acadian cultural merging is also apparent in religious practices. In their desire to enrich the symbolism of the various feast day rites that were a part of the ecclesiastical calendar, the Eudist Fathers, set up the region's first Nativity scene. They also integrated local creative ideas when they used some whalebones to fashion a repository for the celebration of Corpus Christi. With the gradual transition from a community of French clerics (superiors, teachers, and parish priests), to a community largely composed of Canadians, it became possible to strike a balance between these two cultural elements.(NOTE 12)

As an educational institution, Collège Sainte-Anne has played a fundamental role in preserving the French language and in training the region's professional elite, whose influence would then eventually be felt throughout the various levels of society. In addition to academic programs, the college also offered the Acadian community a vast array of cultural activities such as: literary societies, plays, and musical events (concerts, choirs, brass bands, etc.) not to mention numerous athletic competitions.

A Key Influential Factor in the Community

Given the involvement of the Eudist Fathers in various community organizations, their influence extended far beyond the college walls. Here are some examples of their participation in the community at large: national congresses, the Association Acadienne d'Éducation (Nova Scotia), the Camp Jeunesse Acadienne [Acadian Youth Camp], the Société Historique Acadienne de la Baie Sainte-Marie, and the Acadian Federation of Nova Scotia.(NOTE 13)

To be sure, the Eudist Fathers also significantly contributed to religious history through their pastoral endeavours. Their influence in this area went far beyond being responsible for the administration of the two parishes originally assigned to them. Indeed, they would regularly help out other parish priests, especially those from the Baie Sainte-Marie region, as was required by the dictates of the liturgical calendar.(NOTE 14) For instance, they served remote missions, spoke at retreats, organized and supervised parish congregations, as well as the many various masses, feasts and ecclesiastical activities, which are a part of the regular calendar year. Moreover, their objective was to develop appropriate religious practices for the entire year. So they organised various liturgical activities such as the Exercises of the Living Rosary in October, the Forty Hours Devotion around All Saints Day and the solemn devotions in honour of Mary during the month of May. As for the Feast of Corpus Christi [the Body and Blood of Christ], which takes place 60 days after Easter, it constituted the highpoint of the religious year and elicited the highest level of community participation. The Corpus Christi celebration of 1891 at Pointe-de-l'Église was especially memorable. Three thousand worshipers filled the church to over-flowing; the societies of the Holy Childhood, the Holy Angels and the Children of Mary formed a double line flanking a parishioner representing Mary, the Queen of May, who was carried on a sumptuous litter. The procession followed a pathway strewn with flowers, stopping at each of the three repositories, including one crafted for the occasion from the bones of an enormous whale that had been found beached 10 years or so earlier. The bones served as a framework for the altar, propping up the greenery and the flowers that decorated it.(NOTE 15)

As regards their contribution to religious history, the Eudist Fathers deserve special mention for their struggle to influence the clergy of the Maritimes to better integrate into the Acadian way of life of the communities they were serving. They were particularly encouraged to be supportive of the integration and accession of Acadian priests to the local ecclesiastical hierarchy.(NOTE 16) The struggle focused on the issue of appointing Acadians bishops and creating Acadian dioceses. In the end, to meet this need, certain former Collège Sainte-Anne students eventually became century bishops in the early 20th century. Moreover, priests from the college played a prominent role in the creation of the Yarmouth diocese in 1953 and the appointment of an Acadian bishop as its head.(NOTE 17)

The Legacy of the Eudist Fathers

In conclusion, the Congregation's contribution to Nova Scotia's French cultural heritage must not be forgotten; to support this claim, one need only consult the plentiful documentation resulting from the diverse activities of the Collège Sainte-Anne and the various parishes over the years. Nowadays, Université Sainte-Anne has its own Acadian Centre, which has an ample collection of written, audio, and iconographical documents produced or assembled by the religious community. The archives of the Congregation's Provincial Headquarters, located in Charlesbourg, a suburb of Quebec City, also contain wealth of documentary resources. The collection of glass etchings [engraved photos] made at the beginning of the 20th century is particularly noteworthy. In the collection there is a set that was taken in the Petit Bois [The Grove] (see the supplementary document entitled: "Le Petit Bois du Collège Sainte-Anne"). Such collections preserve the memory of authentic period scenery.

At the end of the 1960s, the Eudist Community, like most religious congregations of the period, experienced difficulties in recruiting new members. This explains why it was no longer able to remain financially responsible for Collège Sainte-Anne. On June 21st, 1971, a lay corporation took over the administration of the institution, which was henceforth to be known as Université Sainte-Anne.(NOTE 18) After this latter phase of secularization (this time in Canada) members of the Congregation not only continued to teach at the University for a few more years, but especially to serve in the parishes of South-western Nova Scotia, a mission that continues to this day.

Micheline Laliberté

Professor, Université Sainte-Anne

NOTES

Note 1. For the factors that drove the religious communities to seek lands of refuge, see Guy Laperrière's trilogy Les congrégations religieuses. De la France au Québec. 1880-1914, Québec, Les Presses de l'Université Laval, 1996-2005, 3 vol. Each volume contains one or more sections on the Eudists' particular situation.

Note 2. René LeBlanc et Micheline Laliberté, Sainte-Anne, collège et université, 1890-1990, Nouvelle-Écosse, Chaire d'étude en civilisation acadienne de la Nouvelle-Écosse, 1990, 499 p.

Note 3. R. LeBlanc et M. Laliberté, op. cit., p, 25.

Note 4. L'Évangéline, 16 octobre 1890.

Note 5. Séminaire du Saint Coeur de Marie. Album préparé à l'occasion du cinquantenaire. 1895-1945, [s.l.], 1946, 93p.

Note 6. L'église Sainte-Marie. Un projet des paroissiens à l'occasion du 75e anniversaire de la bénédiction de l'église, Pointe-de-l'Église, N.-É., 1980, 156 p. See also Basile J. Babin, Entre le marteau et l'enclume. Pierre-Marie Dagnaud à la Pointe-de-l'Église, Nouvelle-Écosse, 1899-1908. Une page de l'histoire religieuse de l'Acadie au tournant du siècle, Québec, Maison des Eudistes, 1982, 406 p.

Note 7. R. LeBlanc et M. Laliberté, op. cit., p. 130.

Note 8. Gérald C. Boudreau, L'apostolat du missionnaire Jean Mandé Sigogne et les Acadiens du sud-ouest de la Nouvelle-Écosse, Thèse présentée à la Faculté des études supérieures en vue de l'obtention du grade de Philosophiae Doctor (Ph. D.) en Théologie, Université de Montréal, 1989.

Note 9. R. LeBlanc et M. Laliberté, op. cit.,, pp. 88-89.

Note 10. L'église Sainte-Marie (...), op. cit., p.27; et Luc Noppen, « L'église Sainte-Marie, monument du métissage de modèles bretons et des savoirs-faire acadiens », Le patrimoine religieux de la Nouvelle-Écosse. Signes et paradoxes en Acadie, Port Acadie, 10-12 (2006-2007).

Note 11. See Luc Noppen, op. cit., p. 157-158 for further clarifications.

Note 12. R. LeBlanc et M. Laliberté, op. cit.,, pp. 124-125).

Note 13. Two prizes are given in honour of Father Léger Comeau, an Eudist and key Acadian nationalist and ambassador: the first is a medal awarded by the Société Nationale de l'Acadie, the second is a certificate given by the Fédération Acadienne de la Nouvelle-Écosse [Acadian Federation of Nova Scotia].

Note 14. At various times throughout their history, the Eudist Fathers also served the following parishes: Concessions, Corberrie, Saint-Bernard, Saint-Alphonse, Saint-Joseph du Moine, Chéticamp, Plympton, Wedgeport, Île Surette, Buttes Amirault, Weymouth, Annapolis, Middleton. « Évangélisateurs-formateurs à la suite de saint Jean Eudes », Album-souvenir du centenaire de la présence eudiste en Amérique du nord, Cahiers eudistes, 13 (1990) p. 10.

Note 15. « Les Acadiens de la baie Sainte-Marie à la fin du XIXe siècle ou les paradoxes de quelques pratiques cultu(r)elles », Port Acadie, 10-12 (2006-2007) p. 81-101, in Actes du colloque Le patrimoine religieux de la Nouvelle-Écose. Signes et paradoxes en Acadie.

Note 16. Léon Thériault, « L'acadianisation de l'Église catholique en Acadie », in Les Acadiens des Maritimes. Études Thématiques, Moncton, Centre d'études acadiennes, 1980.

Note 17. Micheline Laliberté, « Un exemple de la trilogie langue, nationalisme et religion : la création du diocèse de Yarmouth », dans G.C. Boudreau, Une dialectique du pouvoir en Acadie. Église et autorité, Montréal, Éditions Fides, 1990. pp. 67-104.

Note 18. Note that on April 30, 1892, the Nova Scotia Government passed an act allowing the college to hand out university degrees. R. LeBlanc et M. Laliberté, op. cit., p. 41.

BIBLIOGRAPHIE

Most of the research for this article was carried out with the help of the Eudist archives in Charlesbourg. Microfilm was the source of most of the information, but original documents were also consulted during visits to the archives.

BABIN, Basile J., Entre le marteau et l'enclume. Pierre-Marie Dagnaud à la Pointe-de-l'Églie, Nouvelle-Écosse, 1899-1908. Une page de l'histoire religieuse de l'Acadie au tournant du siècle, Québec, Maison des Eudistes, 1982, 406p.

BOUDREAU, Gérald C., L'apostolat du missionnaire Jean Mandé Sigogne et les Acadiens du sud-ouest de la Nouvelle-Écosse, Thèse présentée à la Faculté des études supérieures en vue de l'obtention du grade de Philosophiae Doctor (Ph. D.) en Théologie, Université de Montréal, 1989, 251p.

COTARDIÈRE, Georges de la, La Congrégation de Jésus et Marie (Eudistes) au Canada. Cinquante Ans. 1890-1940. Notes et souvenirs, Besançon, Imprimerie Jacques et Demontrond, 1946, 172p.

« Évangélisateurs-formateurs à la suite de saint Jean Eudes », Album-souvenir du centenaire de la présence eudiste en Amérique du nord, Cahiers eudistes, 13 (1990) 40p.

L'église Sainte-Marie. Un projet des paroissiens à l'occasion du 75e anniversaire de la bénédiction de l'église, Pointe-de-l'Église, N.-É., 1980, 156p.

LALIBERTÉ, Micheline, « Un exemple de la trilogie langue, nationalisme et religion : la création du diocèse de Yarmouth », dans G.C. Boudreau, Une dialectique du pouvoir en Acadie. Église et autorité, Montréal, Éditions Fides, 1990. pp. 67-104.

LALIBERTÉ, Micheline, « Les Acadiens de la Baie Sainte-Marie à la fin du XIXe siècle ou les paradoxes de quelques pratiques cultu(r)elles » conférence présentée lors du colloque national « Le patrimoine religieux de la Nouvelle-Écose. Signes et paradoxes en Acadie », dans Port Acadie, 10-12 (2006-2007), pp. 81-100.

LALIBERTÉ, Micheline, « Relations et perceptions entre un peuple et son clergé à la fin du XIXe siècle », conférence présentée lors du colloque international « La résistance des marges », août 2007, à paraître dans le prochain numéro de Port Acadie.

LAPERRIÈRE, Guy, Les congrégations religieuses. De la France au Québec. 1880-1914, Québec, Les Presses de l'Université Laval, 1996-2005, 3 vol. [Tome 1, Premières bourrasques. 1880-1900. 1996, 228p. ; Tome 2, Au plus fort de la tourmente. 1901-1904, 1999, 597p. ; Tome 3, Vers des eaux plus calmes. 1905-1914, 2005, 730p.]

LAPLANTE, Léopold, Chronique du Collège Sainte-Anne : les Pères Eudistes au service de l'Église et de la Communauté, Yarmouth, L'Imprimerie Lescarbot Ltée, 1986,146 p.

LEBLANC, René et LALIBERTÉ, Micheline, Sainte-Anne, collège et université, 1890-1990, Nouvelle-Écosse, Chaire d'étude en civilisation acadienne de la Nouvelle-Écosse, 1990, 499p.

NOPPEN, Luc, « L'église Sainte-Marie, monument du métissage de modèles bretons et des savoirs-faire acadiens », Le patrimoine religieux de la Nouvelle-Écosse. Signes et paradoxes en Acadie, Port Acadie, 10-12 (2006-2007) pp. 149-177.

Sainte-Anne. Cent ans d'images du collège à l'université, 1890-1990, Pointe-de-l'église, 1990, 220p.

SAMSON, André et CUSTEAU, Jacques, Les Eudistes en Amérique du Nord, 1890-1983, Charlesbourg, Service provincial des archives, 1997, 249p.

Séminaire du Saint Coeur de Marie. Album préparé à l'occasion du cinquantenaire. 1895-1945, [s.l.], 1946, 93p.

THÉRIAULT, Léon, « L'acadianisation de l'Église catholique en Acadie », dans Les Acadiens des Maritimes. Études Thématiques, Moncton, Centre d'études acadiennes, 1980, pp. 431-467.