Pointe-à-la Renommée Lighthouse Station (Gaspé)

par Fallu, Jean-Marie

The Pointe-la-Renommée (Gaspé) lighthouse bears witness to Quebec’s maritime history. Beginning in 1880, the wooden lighthouse guided navigators in the region. The first maritime wireless telegraphy station in Canada was then established there in 1904. Three years later, a second, innovative light tower dominated the point. What was unusual about it? It was built of prefabricated cast-iron components. Today, the Pointe-à-la-Renommée heritage site offers visitors a representation of the fascinating history of this point and this lighthouse station. Visitors can learn about the way of life and traditions of the families of lighthouse keepers and maritime wireless telegraph operators. They will also discover that, to preserve this lighthouse, it was moved to the Port of Quebec in 1978. Later, the activism of a citizens’ committee from the village of L’Anse-à-Valleau, convinced of the importance of this key element of their heritage, led to its return to its original location in 1997.

Article disponible en français : Station de phare de Pointe-à-la-Renommée (Gaspésie)

A Point with a Rich Heritage

Pointe-à-la-Renommée, a majestic site overlooking the sea at the entrance to the Gulf of St. Lawrence, provides one of the most beautiful maritime panoramas in Quebec. “Words cannot describe the majestic serenity and calm of this site and the surrounding area.” [Translation] (NOTE 1) The Pointe-à-la-Renommée heritage site is located 60 kilometers northwest of town of Gaspé and 10 kilometers west of the village of L’Anse-à-Valeau. It includes the light tower, the Marconi station, the lightkeeper’s house, the operators’ house, and foundations of the fog alarm and the foundry. Long known as Fame Point, it is now referred to by its French name, Pointe-à-la-Renommée (NOTE 2).

The lighthouse station had been in operation for nearly a hundred years, from 1880 to 1975, when it was dismantled. Reconstituting the various elements of the site and restoring it to its original state had to be done in several stages. The light tower, built in 1907 and moved to Quebec City in 1978, was returned to its original location in 1997. The Marconi station (maritime wireless telegraphy) was reconstituted in 1998. Then, in 2001, the lightkeeper’s house was rebuilt, in the style of the exterior of the first wooden light tower, or lighthouse, which dated back to 1880.

Designated an historic monument by the Town of Gaspé in 2010, the Pointe-à-la-Renommée Lighthouse Station is a testament to the maritime heritage of the Gaspé region and of Canada. It recalls the key role this wireless telegraph station and lighthouse played in the history of navigation.

At the Service of Navigators

Because too many ships had sunk along the Gaspé coastline, Canadian authorities began in the mid-19th century to establish a series of landfall light towers at the mouth of the St. Lawrence. This was also a time of considerable growth of maritime traffic. Almost everything was transported by sea: food, mail, travellers, imported goods, and exports like lumber.

The decision to establish a light tower at Pointe-à-la-Renommée was a response to the urgent need for increased navigational safety along the Gaspé coast between the lighthouses already in place, at Cap-des-Rosiers (1858) and Cap-de-la-Madeleine (1876), and through the Honguedo Strait between Anticosti Island and the Gaspé Peninsula. Built in 1880, the first Pointe-à-la-Renommée lighthouse became an important landmark on the long St. Lawrence seaway.

The original lighthouse was built by Ontario businessman, M.R. Cameron, with a $4,000 grant approved by the Parliament of Canada. The wooden structure was made up of a square, tapered tower, 15.2 meters tall from its base to the top of the lamp, with a keeper’s house attached, the reason it was called a “light-house”. Initially, the tower was white with a horizontal black band. It was painted red in 1903 to make it more visible against the leaves in summer and the snow in autumn, winter and spring. In clear weather, its white light could be seen from a distance of 33 kilometers. The fixed white light was varied by red flashes at twenty second intervals. The light was produced by wick burners, fuelled by kerosene, and amplified through the use of copper parabolic reflectors, which were silver-coated to increase their reflective properties.

Pointe-à-la-Renommée, June 1904: The First Maritime Wireless Telegraph Station

Pointe-à-la-Renommée was part of the adventure of new wireless telegraphy, invented and led by Guglielmo Marconi at the beginning of the 20th century. A memorandum of agreement (NOTE 3), signed on March 17, 1902 by Marconi and Prime Minister Wilfrid Laurier, provided for the construction of facilities for transatlantic communications and communications between lighthouses, coast stations and ships. Pursuant to this agreement, Marconi registered a Canadian subsidiary, the Marconi Wireless Company of Canada, in 1903. One year later, the Canadian Government, represented by the Honourable Raymond Préfontaine, then Minister of Oceans and Fisheries, signed a contract (NOTE 4) with the Marconi Wireless Telegraph Company of Canada for the construction and operation of the first network of maritime wireless telegraph stations in the country, now known as “marine radio stations”.

The first of these stations was built at Pointe-à-la-Renommée, in June 1904. In that year, the lighthouse keeper welcomed engineer Joseph Barridon and his assistant Hugh Lyle (NOTE 5) who, as they stepped out of their “buggy”, announced that they were there to build a “wireless station”. In the 9.1 x 6.7 meter station (NOTE 6), they installed the components of the new Marconi communication system: a spark-gap transmitter, an induction coil and a magnetic receiver. (NOTE 7)

Historian Edward F. Bush, an expert on the history of Canadian lighthouses, has underlined the importance of this network, which expanded rapidly over a ten-year period: “In 1904, for example, wireless facilities were installed at the Fame Point, Belle Isle, Cape Ray, Cape Race, Heath Point and Point Amour lighthouses. By 1915, no fewer than 21 lighthouses below Quebec were radio-equipped.” (NOTE 8)

The Department of Oceans had wireless telegraphy equipment installed in coast stations and also fitted to the ships Stanley, Canada and Minto, in 1904, and the Lady Laurier, in 1905. Eight years later, 90 Canadian ships had already been equipped with wireless telegraph communications systems by the Marconi Wireless Telegraph Company of Canada (NOTE 9).

In Defence of the Country

Wireless telegraphy meant that the Pointe-à-la-Renommée station played an important role in the two great world wars of the 20th century. During the First World War (1914-1918), the Canadian Army had a base at Pointe-à-la-Renommée, establishing a camp and barracks and communications monitoring systems there. In the Second World War (1939-1945), the station once again played a key role in surveillance and information-gathering for the Department of National Defence, particularly during the Battle of the Saint Lawrence (1942-1944). Military authorities first learned from the Pointe-à-la-Renommée station, on May 12, 1942, that a German submarine had torpedoed the first two ships to sink in Canadian waters: the Nicoya and the Leto. Nearly fifty survivors were rescued by residents of the villages of L’Anse-à-Valleau and Cloridorme.

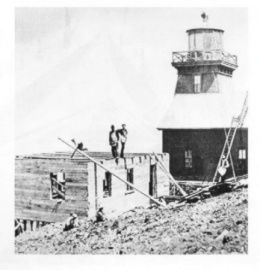

The Second Lighthouse, 1907: A New Construction Method

After more than 25 years of loyal service, the first wooden lighthouse (1880), which was expensive to maintain, was replaced by a tower constructed of prefabricated cast-iron panels. This tower had several advantages: a relatively low cost, ease of assembly, great durability and minimal maintenance. This second light (1907) was one of the first in Canada to use this method of construction, already established in Newfoundland. Prefabricated cast-iron panels were bolted together around the outside of the tower, an innovative method at the time.

Originally painted completely red, the cylindrical tower was 15.5 meters tall and 3.6 meters in diameter, with an outside walkway around the top. The lighthouse lens sat 190 feet above high tide level. Its light could be seen from a distance of 83 kilometers; on a clear day, it could be seen from as far away as Anticosti Island. The new lighthouse was one of a series built along the St. Lawrence during this period: La Martre (1906), Matane (1907), Cap-de-la-Madeleine (1908) and Pointe de Mitis and Cap-Chat (1909). In contrast to Pointe-à-la-Renommée, the other light towers were built of reinforced concrete, except the one at La Martre, which was wooden.

Families of the Keepers and the Operators: A Story of Tradition and a Sense of Belonging

Isolated from the rest of the population, the families of the lighthouse keepers and wireless operators developed a feeling of solidarity among themselves and a sense of belonging to the Pointe-à-la-Renommée site. A largely self-sufficient community developed there over several generations. The members of this community of coastal and maritime communicators forged a tradition of people of the sea, living proudly and courageously, in circumstances characterized by geographical isolation but also, paradoxically, by contact with the wider world.

The wireless telegraph meant that they often received news from ships arriving from Europe and entering the St. Lawrence before it had reached the larger centres. Through the lives of its lighthouse keepers and its wireless operators, Pointe-à-la-Renommée was imbued with a rich maritime tradition.

Several of these keepers made their mark on the history of Pointe-à-la-Renommeé, from the first, James Ascah (1880-1913), to the last, Yvon Élément, whose career ended in 1975. From generation to generation, the Ascahs formed a true dynasty of lighthouse keepers at Pointe-à-la-Renommée. Between 1880 and 1943, members of this family were in charge of all of the station’s activities, from the maintenance of the lighthouse, the lighting and optical apparatus and the mechanical equipment, to the operation of the telegraph (by wire), the signal tower and the post office.

Repatriating a Piece of Heritage, Recovering an Identity

Marine radio station operations ceased at Pointe-à-la-Renommée in 1957, at which time they were relocated at Rivière-au-Renard (26 km to the east). In 1975, the lighthouse was shut down for good. The Canadian Coast Guard offered it to the Société historique de la Gaspésie, which declined the opportunity to acquire and manage the site (NOTE 10). Once abandoned, the site fell victim to vandalism. The Coast Guard’s concern about preserving this valuable piece of heritage led it to dismantle the light tower and transport it to Quebec City in 1978. In 1981, it was reconstructed in front of Coast Guard’s administrative headquarters in the Old Port of Quebec (NOTE 11), in the midst of excited preparations for the 1984 maritime festival being planned for Quebec.

From 1981 to 1992, individuals and organizations from the Gaspé region contacted the Canadian Coast Guard to protest the move of the lighthouse to Quebec, an action historian Mario Mimeault described as “cultural plundering”. In spite of these protests, nothing concrete happened until the Comité local de développement de L’Anse-à-Valleau took action in 1992. The region’s economy had been hit hard at the beginning of the 1990s by the closure of its fish plant. Worried about the situation, residents tried to identify other options for community development. In their minds, the lighthouse was the symbol of an entire social and economic way of life that no longer existed, but that had characterized their region for several generations. Many felt that the departure of the lighthouse had created a huge vacuum and caused a certain loss of collective identity. “Acculturation was definitely a factor in the move of the lighthouse to Quebec City. The end result seems to have been a loss of identity among the residents of L’Anse-à-Valleau.” [Translation] (NOTE 12)

These were the challenging circumstances facing the Comité local de développement de L’Anse-à-Valleau when it decided to revive Pointe-à-la-Renommée by having the lighthouse returned and making it the key component of a recreation and tourism development project. For the women running the committee, getting the lighthouse back was the only way to breathe new life into the local economy and to rebuild a sense of community. Subsequent events proved them right. On November 3, 1997, the people of L’Anse-à-Valleau watched as their lighthouse came home. The feeling of pride was palpable in this community, which had known such trying times and which was now re-appropriating a vital symbol of its cultural identity. Each headline in the press tried to outdo the other in hailing the event: La loi du plus phare (Rule of the Fittest), Le phare prodigue (The Prodigal Lighthouse), Le retour du phare ouest (Return of the Western Lighthouse), Le phare enfin de retour à Pointe-à-la-Renommé après un très long voyage (The Lighthouse Home Again in Pointe-à-la-Renommé After Its Long Voyage), etc.

For the members of the committee, victory was sweet. The repatriation of the lighthouse put an end to a five-year battle with Canadian Coast Guard authorities, and also to the scepticism of those who believed that the battle was lost before it began. Today, the Site historique du phare de Pointe-à-la-Renommée is a source of regional pride and one of the tourist destinations that make up the network known as the Quebec Lighthouse Trail (NOTE 13). The story of this battle demonstrates that the value of our heritage is enhanced through our belief in it and the investment of our time and energy to making it important. This fight – led by women –is also a good example of tenacity based on the principle of respecting the integrity of a heritage asset’s place of origin.

Jean-Marie Fallu

Historian and Museologist

President, Patrimoine 1534, Gaspé

Additional DocumentsSome documents require an additional plugin to be consulted

Images

-

À Pointe-à-la-Renommé

À Pointe-à-la-Renommé

e, deux opérate... -

Au milieu de nulle pa

Au milieu de nulle pa

rt... phare de ... -

Baraque de l’armée co

Baraque de l’armée co

nstruite à la s... -

Bateau de pêche amarr

Bateau de pêche amarr

é à L'Anse-à-V...

-

Brise du large à l'An

Brise du large à l'An

se-à-Valleau, 2... -

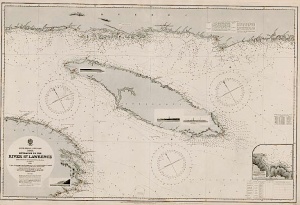

Carte montrant l'embo

Carte montrant l'embo

uchure du fleuv... -

Carte postale montran

Carte postale montran

t des chalutier... -

Carte postale montran

Carte postale montran

t L'Anse-à-Val...

-

Carte postale montran

Carte postale montran

t L'Anse-à-Val... -

Carte postale montran

Carte postale montran

t L'Anse-à-Val... -

Clé morse, ou manipu

Clé morse, ou manipu

lateur: outil i... -

Elinore Nelson à Poin

Elinore Nelson à Poin

te-à-la-Renommé...

-

Guglielmo Marconi

Guglielmo Marconi

-

Guglielmo Marconi

Guglielmo Marconi

-

Harmonie du soir (Jea

Harmonie du soir (Jea

n-Pierre Gagnon... -

James Ascah, premier

James Ascah, premier

gardien du phar...

-

L'Anse à Valleau, 19

L'Anse à Valleau, 19

41 -

L'anse à Valleau,193

L'anse à Valleau,193

4 -

L'Anse-à-Valleau, co

L'Anse-à-Valleau, co

mté Gaspé-Est... -

La station de phare d

La station de phare d

e Pointe-à-la-R...

-

La station du phare d

La station du phare d

e Pointe-à-la-R... -

La station Marconi et

La station Marconi et

le phare de Po... -

La station TSF Marcon

La station TSF Marcon

i en constructi... -

Le phare de Pointe-à-

Le phare de Pointe-à-

la-Renommée et ...

-

Le phare en exil à Qu

Le phare en exil à Qu

ébec -

Le phare est remonté

Le phare est remonté

sur son site d’... -

Le sémaphore et la st

Le sémaphore et la st

ation Marconi d... -

Le village de L'Anse-

Le village de L'Anse-

à-Valleau, Qué...

-

Les derniers opérateu

Les derniers opérateu

rs de la statio... -

Les rescapés du Nicoy

Les rescapés du Nicoy

a, coulé par un... -

Lloyd Nelson, opérate

Lloyd Nelson, opérate

ur, dans les an... -

Panorama en allant ve

Panorama en allant ve

rs Pointe-à-la...

-

Péninsule de l'Anse-a

Péninsule de l'Anse-a

̀-Valleau, sept... -

Phare de Pointe-à-la-

Phare de Pointe-à-la-

Renommée (Jean-... -

Phare de Pointe-à-la-

Phare de Pointe-à-la-

Renommée (Jean-... -

Phare de Pointe-à-la-

Phare de Pointe-à-la-

Renommée, 2006...

-

Phare de Pointe-à-la-

Phare de Pointe-à-la-

Renommée, 2010... -

Plan rapproché d'une

Plan rapproché d'une

carte montrant ... -

Pointe-à-la-Renommée,

Pointe-à-la-Renommée,

2010 -

Pointe-à-la-Renommé

Pointe-à-la-Renommé

e, anse à Valle...

-

Pointe-à-la-Renommée,

Pointe-à-la-Renommée,

avant et après... -

Promenade à L'Anse à

Promenade à L'Anse à

Valleau -

Régina Lisik-Nelson a

Régina Lisik-Nelson a

véçu à Pointe-... -

Timbre de Marconi (18

Timbre de Marconi (18

74-1937) émis p...

-

Toujours plus loin (J

Toujours plus loin (J

ean-Pierre Gagn... -

Tour guidé dans la st

Tour guidé dans la st

ation de phare ... -

Trop de watts pour le

Trop de watts pour le

s compter... vu... -

Un opérateur, Lloyd N

Un opérateur, Lloyd N

elson, à côté d...

Documents PDF

-

Des technologies d'avant-garde: signaux sonores, sémaphore et télégraphie par câble

Des technologies d'avant-garde: signaux sonores, sémaphore et télégraphie par câble

-

Les Ascah, une dynastie de gardiens de phare

Les Ascah, une dynastie de gardiens de phare

Catégories

Notes

1. Pierre Rastoul and Alain Ross, La Gaspésie, de Grosses-Roches à Gaspé : itinéraire culturel, Montréal, Beauchemin; Québec, Éditeur officiel du Québec, 1978, p. 169.

2. Two possible explanations have been given for the name. The first is that the point was named for a ship from La Rochelle, La Renommée, which sank off Anticosti Island in 1736. The second theory is that survivors of a shipwreck starved on the point and the spot was, therefore, called Pointe-à-la-Faim (Hunger Point), later translated incorrectly into English as Fame Point. Ultimately, Francophones from the Gaspé region translated the name back into French; Fame was translated as Renommée and the point became Pointe-à-la-Renommée!

3. “Mémoire concernant la compagnie de télégraphie sans fil de Marconi », Sessional Documents, no. 51a, 1902, quoted in Pierre Pagé, Histoire de la radio au Québec : informaton, éducation, culture, Montréal, Fides, 2007, p. 30.

4. Library and Archives Canada, Department of Transport Fonds, RG12, E4, vol. 396, file 5604-12 (4).

5. According to Lloyd Nelson, “Goodbye Old Fame Point”, News on the DOT, Ottawa, Department of Transport, December 1957, p. 2, quoted in Stephan Dubreuil, Come Quick, Danger, the History of Marine Radio in Canada, Ottawa, Oceans and Fisheries Canada, Coast Guard, 1998, p. 9.

6. Library and Archives Canada, RG12, Department of Transport Fonds, series E4, volume 396, file 5604-12 (4), “Specification of Buildings to Be Built by the Marconi Company at Stations of Government Telegraphing”.

7. The first communication between a ship and the first operational Canadian marine radio station took place on June 25, 1904. The telegraph operator on the ship, the Parisian, sent 16 messages to the Point-à-la-Renommée coast station and received one message back. They were in communication for one hour and eight minutes. This first communication was carefully recorded in the Pointe-à-la-Renommée “Log Book”: “Saturday June 25, 1904, 8h25 p.m. In communication with Parisian bound east, 23 miles west. 9h33 p.m. finish with PN. Read 16, sent 1. Communication perfect.” (Library and Archives Canada, MG28, Canadian Marconi Company Fonds, seroes III 72, volume 81, “Log Book of Fame Point, July 20, 1904 to 1915”).

8. Edward F. Bush, The Canadian Lighthouse, Ottawa, Parks Canada, 1980, pp. 24-25.

9. Library and Archives of Canada, MG28, Canadian Marconi Company Fonds, series II 72, volume 7, “Canadian Marconi Company History”, p. 12.

10. Letter from Pierre F. Boisvert, Executive Director, Canadian Coast Guard, to Pascale Gagnon, Curator, Musée de la Gaspésie, January 17, 1995.

11. Letter from Jacques Lorquet, District Manager, Transport Canada, to Bernard Boucher, Executive Director, Cultural Council of Eastern Quebec, January 25, 1982.

12. Letter from Claude Brunet, Ralliement gaspésien et madelinot, to Pierre F. Boisvert, Executive Director, Canadian Coast Guard, March 8, 1995.

13. See Comité local de développement de L’Anse-à-Valleau, Le site historique de Pointe-à-la-Renommée [on-line], http://www.pointe-a-la-renommee.com; and Corporation des gestionnaires de phares de l’estuaire et du golfe Saint-Laurent, La route des phares du Québec [on-line], http://www.routedesphares.qc.ca.

Bibliographie

Boudreau, Henri-Paul, Cette mer cruelle, Sainte-Julie (Qc), Éditions nord-côtières, 2000, 308 p.

Bush, Edward F., Les phares du Canada, Ottawa, Parcs Canada, 1980, p. 5-121.

Dubreuil, Stephan, CQD, toujours à l’écoute : histoire de la radio maritime au Canada, Ottawa, Pêches et Océans Canada, Garde côtière, 1998, 140 p.

Fallu, Jean-Marie, « Le rapatriement du phare de Pointe-à-la-Renommée : l’identité retrouvée », Continuité, no 77, été 1998, p. 47-52.

Fallu, Jean-Marie, et Danièle Raby, pour le Comité local de développement de L’Anse-à-Valleau, Demande de désignation de la Station de phare de Pointe-à-la-Renommée à la Commission des lieux et monuments historiques du Canada (CLMHC), mars 2008, 23 p. et annexes.

Halley, Patrice, Les sentinelles du Saint-Laurent : sur la route des phares du Québec, Montréal, Éditions de l’Homme, 2002, 246 p.

Historique de Pointe-à-la-Renommée (Fame Point), L’Anse-à-Valleau (Qc), Comité local de développement de L’Anse-à-Valleau, 2003, 114 p.

Lamoureux, Marcel, « Le phare de Pointe-à-la-Renommée : un mode de vie imprégné par la mer et les communications », Gaspésie, vol. 28, nos 3-4 (nos 111-112), septembre-décembre 1990, p. 14-24.

Les aventures du phare voyageur, 1907-2007, Ville de Gaspé, n. p.

Lisik-Nelson, Regina, Les années à Pointe à la Renommée : souvenirs d’une décennie dans la Gaspésie, 1949-1959, Ottawa, R. Lisik-Nelson, 1998, 100 p.

Luce, Adrienne, « Pointe-à-la-Renommée : une histoire de pêche et de femmes », Gaspésie, vol. 17, no 66, avril-juin 1979, p. 25-33.

Pagé, Pierre, Histoire de la radio au Québec : information, éducation, culture, Montréal, Fides, 2007, 488 p.

Paradis, Jean, Historique de la station de phare de Pointe à la Renommée, Québec, Garde côtière canadienne, 1985, 18 p.

Vaillancourt, Linda, Historique des télécommunications et de l’électronique, Garde côtière canadienne, Région des Laurentides, septembre 1982, 40 p.

Whitney, Dudley, The Lighthouse, Toronto, McClelland and Stewart, 1975, 255 p.