Maillardville, a francophone community in British Columbia

par Lapointe, Geneviève

For more than two centuries, French-speaking people have been in British Columbia. Francophone members of the Mackenzie and Fraser expeditions crossed the Rockies on the way to the Pacific. Later, voyageurs working in the fur trade settled in various parts of the province over the course of the nineteenth century. From 1909 on, the Maillardville community has been an example of the role played by French Canadians in development of the province. Several hundred of them came to British Columbia, recruited to work in a sawmill on the banks of the Fraser River east of Vancouver. At that time, Fraser Mills was a small company town surrounded by forest. Within a few years, a village including a church, a convent, a school, a post office, a police and fire station, and a number of businesses had replaced the dense forest north of the sawmill. The francophone village of Maillardville was born, and would go through many changes over the decades.

Article disponible en français : Maillardville : une communauté francophone en Colombie-Britannique

Maillardville today

Today, although francophones represent only 2.3% of this urban area, Maillardville does still exist; there is no doubt that the cultural and historical heritage of the first French-Canadians is still present. Street names, cultural activities, community associations, the Festival du Bois, the two churches and the renewal projects show how active and dynamic the Maillardville francophone community is.

The founding of Maillardville

Maillardville's history is closely related to the development of the forest industry. In 1909 the Fraser River Lumber Company (which became the Canadian Western Lumber Company the following year) decided to recruit French-Canadian workers, who were well known for their expertise in forestry. The decision to hire workers from Quebec and francophone Ontario was part of the company's strategy to replace its Chinese, Japanese and South Asian workers. In the context of the systemic anti-Asian racism of the time (NOTE 1), the company sought to have an entirely white work force.

To encourage French Canadian families to settle in British Columbia, the Fraser River Lumber Company promised to provide wood to build houses, a school, and a church. The company also paid for the train trip to British Columbia. The first contingent of French Canadians, consisting of 110 workers and their families, arrived in Fraser Mills on 27 September 1909. (NOTE 2). Eight months later, in May 1910, another group arrived, increasing the ranks of what was to become the largest francophone community west of the Rockies.

Father Maillard

Although they worked on average 10 hours a day six days a week, the newly arrived francophones managed to build houses, a French-language school, and a Catholic church north of Fraser Mills. The church, dedicated to Our Lady of Lourdes, was built just in time for the 1910 Christmas mass to be celebrated. In 1913 the little francophone village was growing fast; it had a population of more than 500 persons (NOTE 3), and had its first post office. The village was given the name of Maillardville, in honour of Father Edmond Maillard OMI, the first priest of the Notre-Dame-de-Lourdes parish.

Despite the wishes of its residents, Maillardville never became an independent municipality; it remained part of the district, and later the city, of Coquitlam. The little French-Canadian quarter soon became a central part of the young municipality. The first city hall offices were temporarily installed in the house of Émeri Paré senior, a francophone resident of Maillardville who was from 1913 to 1927 the first chief of police and fire chief of the municipality of Coquitlam.

From the beginning of the little village, French Canadians formed a community that played a leading role in development of the area. Unlike employees from China, Japan and India, who were considered temporary workers and who for the most part either were single or had left families in their country of origin, the French Canadians working at Fraser Mills could bring their wives and children, and thus were able to build the province's first francophone parish on the banks of the Fraser River.

The Fraser Mills strike of 1931

During the Depression, work conditions worsened considerably at Fraser Mills. Workers were fired when they refused to work overtime, and beginning in 1930, salaries began to drop sharply. Between January 1930 and September 1931, the company imposed five significant salary decreases. The workers, supported by the Lumber Workers' Industrial Union (LWIU), voted in favour of a strike on 16 September 1931. The French Canadians were very much involved in the conflict; though representing only 18% of the workforce, they made up half the membership of strike committees (NOTE 4).

Building at 1133 Cartier Street, Maillardville, built in the 1930s. This is one of the rare commercial buildings surviving in this area. It served in turn as premises for a shoemaker, a dry-cleaner, a furniture-maker, and a grocery store.

The strike revealed the social cohesion and solidarity of the Maillardville francophone community. At that time the little village was still relatively isolated geographically. Most residents worked for the same company and belonged to the same social class. Inter-family connections among the francophones in the community were also very important (NOTE 5), and cultural, social and family activities were centred around the Catholic parish, the church and the school. The people of Maillardville were thus joined in solidarity, and the whole community supported the strikers during the conflict. The women set up a community kitchen, organized petitions to support arrested workers, and took part in the picketing with their children. The strike lasted two and a half months. Although the workers did not make any substantial gains, and their union was still not recognized by the employer, the employer did stop the continual lowering of salaries (NOTE 6). Many Maillardville families had a hard time after the strike. Some francophone workers were put on a blacklist, which prevented them from finding work later at Fraser Mills and in the surrounding area.

A wave of migration from the Prairies

With the Depression of the 1930s, French Canadians from the Prairies came to Maillardville in search of better living conditions further west. The economic boom associated with World War II caused this wave of settlers to continue into the 1940s. The new settlers, from francophone communities such as Willow Bunch, Saskatchewan, and Saint-Boniface, Manitoba, increased the ranks of British Columbia's French-language community.

This amounted to a real demographic explosion, leading to the establishment of a second Catholic parish to receive and serve the new arrivals. The Notre-Dame-de-Fatima parish, including a church and a school, was founded in 1946, and in the same year the Caisse populaire de Maillardville was established, an institution essential for the socioeconomic development of the francophone community.

The 1951 school strike

Despite the economic recovery in the after-war years, some Maillardville francophone parents found it increasingly difficult to pay the supplementary fees for the separate school system. Not only did they have to pay school taxes for English-language public schools, but also cover the full costs of their own Catholic French-language schools. In addition, unlike the case for English-language public schools, francophone parents did not have access to free transportation for students, and had to pay for school books and medical services.

To protest against this situation, the Maillardville Catholic schools went on strike on 2 April 1951. The religious directors and parents of the Notre-Dame-de-Lourdes and Notre-Dame-de-Fatima schools decided to send their 840 pupils to the Coquitlam public schools, to put pressure on the provincial government to finance the francophone schools of Maillardville. The strike caused a great stir throughout Canada, and francophones in other provinces provided moral and financial support to the strikers.

At that time, the school was at the heart of social, community and religious life of the Maillardville francophones. Protecting their language, faith and culture, it held great importance for parents who wanted to transmit their French Canadian values and customs. The promise of a French school had attracted the first contingent of French Canadians to British Columbia. It is not surprising that the francophones of Maillardville had recourse to a strike to protect their system of independent schools.

The 1951 strike, which lasted a year, had limited results. Although the government agreed to finance medical services and to subsidize the purchase of school books, the Soeurs de l'Enfant-Jésus, who had provided instruction in French for more than forty years, had to give up their work, and the secondary school program in Maillardville was abolished. The strike also exposed a generation of francophones to the majority English schools, and some students remained in English-language schools after the conflict was resolved.

Past, present and future of French in Maillardville

In the last third of the twentieth century, Maillardville's francophone population decreased considerably (NOTE 7). There are many reasons for this: marriages or common-law relationships between francophones and non-francophones, the fact that many descendants of the first francophones had to leave Maillardville in the 1960s and 1970s because they could not find affordable housing, the massive arrival of non-francophones in the area, and the gradual reduction of employment available at Fraser Mills, until the final closure of the sawmill in 2001. As a result of this demographic decline, French is spoken much less in Maillardville than in the past. In 2001, the local public school had to end a program that allowed francophone children to receive their education in French, for lack of material resources necessary to meet the increasing demand. This program is now offered at the École des Pionniers de Maillardville, located in the neighbouring city of Port Coquitlam.

Preserving the francophone heritage

Although francophones now represent only a small percentage of Coquitlam's population (2.3% in 2006) Maillardville's cultural and historical heritage is still very evident. Many francophone institutions, founded in recent decades, are helping to keep culture and traditions alive in this community.

Since 1955 the Association des Scouts francophones de Maillardville has offered activities in French for young people of the region. The Foyer Maillard, a centre for seniors created in 1969, still provides bilingual services to its residents. Many activities have also been undertaken carried out in the artistic and community areas, including the choir Les Échos du Pacific (founded in 1973) and the Festival du Bois, an annual event celebrating the history and heritage of Maillardville's residents. In 2008, more than 17,000 visitors attended this event, the only one of its kind in British Columbia, offering francophone music performances and traditional French Canadian food. Organized by the Société francophone de Maillardville, whose mission is to "to promote, represent and defend the rights and interests of the francophones of Maillardville and the surrounding area, and to maintain French Canadian language and culture" (NOTE 8), the Festival du Bois continues to be an occasion gathering together francophones from Maillardville and other areas, as well as francophiles.

In recent years, various projects have been carried out to preserve the material heritage of the old village of Maillardville. Heritage Square (Carré Héritage) is certainly the most visible heritage site. This historic site, inaugurated in 1999, includes a museum (Mackin House), an arts and culture centre (the Place des Arts), the old Fraser Mills train station transformed into a railroad museum, gardens, walks, and outdoor historical objects.

The Mackin House museum, located in the former residence of the Fraser Mills manager, Henry J. Mackin, offers a permanent display on the history of Maillardville and Fraser Mills. This display, including a collection of more than 700 historical photographs, presents daily life at Maillardville from 1909 to 1960. These archives were assembled by Antonio G. Paré, grandson of the former police chief Émeri Paré senior. Bilingual display panels have been installed throughout the area to identify places and to recall important events in the history of the community. A brochure with the title "Maillardville" recommends a tourist circuit leading to heritage houses built by the first residents of Maillardville, and the historic Notre-Dame-de-Lourdes church.

In addition to these activities, the City of Coquitlam recently undertook a project to revitalize the francophone business district of the old Maillardville village (NOTE 9). In partnership with all three levels of government, francophone community groups, and private businesses, and focusing on Maillardville's French Canadian heritage and the community's rich history, the City hopes to attract many francophone businesses. Bakeries, outdoor cafés, jazz clubs and boutiques could open in the old town centre, making it a dynamic and interactive urban cluster.

Maillardville, which developed along with its successive waves of francophone migration, hopes once again to attract francophones from across Canada and from abroad. In the meantime Maillardville residents, be they francophone, non-francophone or francophile, continue to work together to promote French and to preserve, share and celebrate the rich francophone heritage of this unique British Columbian community.

Geneviève Lapointe

P.H.D. in History

Université Laval

Additional DocumentsSome documents require an additional plugin to be consulted

Images

-

Affiche expliquant la

Affiche expliquant la

revitalisation... -

Ancienne gare de Mail

Ancienne gare de Mail

lardville -

Bâtiment du 1133, rue

Bâtiment du 1133, rue

Cartier, à Mai... -

Bénédiction de l'Écol

Bénédiction de l'Écol

e Haute, Mailla...

-

Courtepointe géante c

Courtepointe géante c

réée par des ré... -

École Fatima à Mailla

École Fatima à Mailla

rdville, vers 1... -

Église Notre-Dame-De-

Église Notre-Dame-De-

Lourdes, située... -

Enfant devant une mur

Enfant devant une mur

ale à l'occasio...

-

Kiosque des Scouts fr

Kiosque des Scouts fr

ancophones de M... -

L'un des panneaux app

L'un des panneaux app

osés dans le qu... -

Le père Maillard

Le père Maillard

-

Maison Beaubieu, situ

Maison Beaubieu, situ

ée au 1125 rue ...

-

Maison du 1120, avenu

Maison du 1120, avenu

e Brunette, à M... -

Maison du 1308, rue C

Maison du 1308, rue C

artier, à Maill... -

Maison du 307, rue Bé

Maison du 307, rue Bé

gin, à Maillard... -

Panneaux de signalisa

Panneaux de signalisa

tion de rues à ...

-

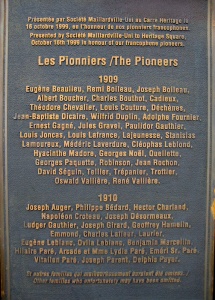

Plaque commémorant le

Plaque commémorant le

s pionniers can... -

Porte de la Canadian

Porte de la Canadian

Western Lumber -

Tour d'horloge de Mai

Tour d'horloge de Mai

llardville, 200... -

Une poutine, mets emb

Une poutine, mets emb

lématique du Qu...

Documents PDF

-

La paroisse Notre-Dame de Lourdes (fiche, 1 page)

La paroisse Notre-Dame de Lourdes (fiche, 1 page)

-

Maillardville toujours! Une promenade à travers l'histoire (dépliant, 3 pages)

Maillardville toujours! Une promenade à travers l'histoire (dépliant, 3 pages)

Hyperliens

- Archives authentiques de l’histoire des francophones de Colombie-Britannique

- Portrait de la francophonie en Colombie-Britannique

- Maillardville 100 years, 1909-2009

- Société francophone de Maillardville

- Histoire de la communauté francophone en Colombie-Britannique

Catégories

Notes

1. Examples of systemic racism include the head tax levied on Chinese immigrants, and the "continuous journey" regulation that prevented immigrants from entering the country unless they had come directly from their country of origin. This regulation, passed in 1908, was mainly intended to prevent immigration from India.

2. John Ray Stewart, French Canadian Settlements in British Columbia, M.A. thesis, University of British Columbia, Vancouver, 1956, p. 46.

3. "Maillardville Shows Remarkable Growth", Coquitlam Star, 1 October 1913, cited in Alain J. Boire, "Maillardville -100 Years, 1909-2009", Maillardville Residents' Association, http://www.maillardvilleresidents.ca/1909-3.htm, consulted 18 June 2011.

4. M. Jeanne Meyers Williams, Ethnicity and Class Conflict at Maillardville/Fraser Mills: The Strike of 1931, M. A. thesis, Simon Fraser University, Burnaby, B.C., 1982, p. 42.

5. For example, one Maillardville family was related to 27 others by marriage (ibid.).

7. The census reports 3,300 native speakers of French at Coquitlam in 1971. There were only 2,515 in 1976, and 1,895 in 2006 (Statistics Canada, population censuses for 1971, 1976 and 2006).

8. Société francophone de Maillardville, "Mission", http://www.maillardville.com/index.php?option=com_content&view=article&id=49&Itemid=54&lang=fr, consulted 18 June 2011.

9. City of Coquitlam, "Maillardville Revitalization: Rebuilding BC’s Historic French Village", Flaunt Your Frenchness!, http://www.coquitlam.ca/_Flaunt+Your+Frenchness/Maillardville+Revitalization.htm, consulted 17 June 2011.

Bibliographie

Frenette, Yves, Brève histoire des Canadiens français, Montréal, Boréal, 1998, 209 p.

Paré, Antonio G., My Grandad the Policeman, Coquitlam (C.-B.), A. G. Paré, 1994.

Paré, Antonio G., My Memoirs of Le Vieux Maillardville : Its Founding People, Their Families, and Where They Live, Coquitlam (C.-B.), A. G. Paré, 1996.

Stewart, John Ray, French Canadian Settlements in British Columbia, mémoire de maîtrise, University of British Columbia, Vancouver, 1956, 163 f.

Villeneuve, Paul Yvon, « Maillardville : à l’ouest rien de nouveau », Cahiers de géographie du Québec, vol. 23, no 58, 1979, p. 157-164.

Williams, M. Jeanne Meyers, Ethnicity and Class Conflict at Maillardville/Fraser Mills : The Strike of 1931, mémoire de maîtrise, Simon Fraser University, Burnaby (C.-B.), 1982, 127 f.

Young, Andrew, Nadia Carvalho et Aleksandra Brzozowski, Heritage Inventory : Maillardville [en ligne], Coquitlam (C.-B.), City of Coquitlam, Community Planning Division, 2007, 85 p., http://www.coquitlam.ca/NR/rdonlyres/B8C93AF6-62EF-43CE-81C8-A2E05C1568FE/69778/MaillardvilleHeritageInventoryRevised2007x1.pdf.