Place-Royale: Where Quebec City Began

par Couvrette, Sébastien

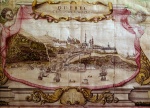

Place-Royale in Quebec City is a historical and archaeological site unique in North America. Considered the birthplace of French America, it played a major role in the social and economic development of the French, and later English, St. Lawrence River colony between the 17th and 19th centuries. Beginning in the 1860s, competition from the Port of Montreal led to the decline of Quebec City’s port and, by extension, the Place-Royale district. In the 1940s, its state of dilapidation prompted plans for an ambitious reconstruction project that was completed in the 1970s and 1980s to restore its French colonial character. Archaeological excavations and historical research conducted during this period revealed the extraordinary heritage value of America’s first French city centre.

Article disponible en français : Place-Royale à Québec, l’origine d’une ville

An Important Historical and Archaeological Site

The extensive reconstruction work completed in Place-Royale in the 1970s and 1980s revealed architectural elements characteristic of the French Ancien Régime (NOTE 1). Reconstruction work was completed in parallel with archaeological excavations that uncovered a great many artefacts demonstrating the site’s long history of human occupation, first by Amerindians, then by Europeans (NOTE 2). The discoveries made during the work in Place-Royale yielded a treasure trove of information about its commercial and residential functions over the different periods of human occupation. The archaeological collection put together with artefacts found during the excavations contains nearly 14,000 restored and documented objects (NOTE 3), a historical and archaeological treasure trove that sheds light on numerous aspects of early Quebec’s material heritage and cultural practices.

The First European Presence

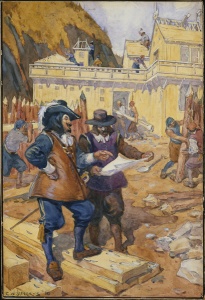

In 1975, the first archaeological excavations were undertaken in front of Notre-Dame-des-Victoires Church in search of the foundations of Champlain’s Habitation (NOTE 4). Additional excavations were conducted later in the 1970s and into the 1980s to explore the site further. Records and artefacts indicate that Champlain’s Habitation was more than just a trading post and storehouse for furs, provisions, arms, and munitions; it was also where the first colonists lived. Here they found shelter from inclement weather and the cold as well as from potential attacks by hostile Amerindian tribes and the British (NOTE 5). The artefacts and ecofacts—animal, mineral, and vegetable remains—recovered from the sedimentary layers dating from 1610 to 1630 reveal the cultural and food practices of the French at the time, who borrowed some aspects of aboriginal culture such as tobacco use. Among the numerous fragments of stoneware, earthenware, porcelain, and clay and terra cotta pipes, the archaeologists also found a lead inkstand that may have belonged to Champlain.

A Market Square

In the 1630s and 1640s, the area around Champlain’s Habitation gradually developed. Under governor Charles Huault de Montmagny, who arrived in the colony in 1636, streets and lots were laid out around Place-Royale as the settlement began to take shape. The moat surrounding the Habitation was filled in to make way for houses and commercial buildings and the Habitation itself was converted into the King’s Storehouse. Once filled in, the space in front of the storehouse became a public square. It was here that the colonial authorities posted their decrees and carried out public executions. And it was here that a market was held starting around 1640 (NOTE 6).

Beginning in the 1650s, freedom of trade, in effect since 1648, and the proximity of the port attracted many merchants and contributed to the city’s development. From a dozen-odd homes in the mid-17th century, the settlement grew rapidly, leading colonial authorities to regulate construction, implement urban planning and enact laws governing residents’ behaviour (NOTE 7). By 1680, about 300 people were living in and around Place-Royale, more than twice as many as 15 years before.

The Fire of 1682

Most of the approximately 60 houses in the area were single-story wooden dwellings with plank or cedar shingle roofs. Homes were built adjacent to one another, separated only by party walls. Consequently, when a fire broke out in 1682, it spread quickly and grew extraordinarily intense. Despite the fire prevention measures taken by Governor Frontenac, the blaze caused considerable damage, destroying most homes (NOTE 8) and setting of an explosion that left the King’s Storehouse in ruins. The vacated lot would be the future site of Notre-Dame-des-Victoires Church, built in 1688.

In the following decades, Place-Royale would be rebuilt in keeping with planning principles intended to prevent a tragic event like the 1682 fire. Two- and even three-story houses were built partially or completely in stone with thick firewalls rising above the roofline to prevent the spread of fire, although mansard roofs were covered with cedar planks or shingles in violation of the prohibition of those materials. From that point forward, construction in Place-Royale quickly reached its limit and the district changed little until the end of the French Regime.

Rebuilding. But in the French or the English style?

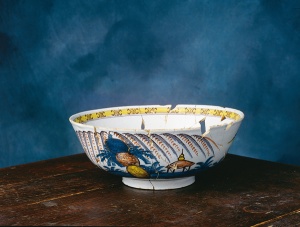

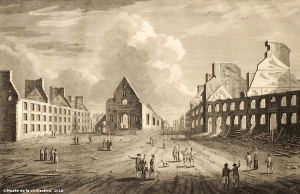

During the 1759 siege of Quebec, British army bombardments destroyed the homes in Place-Royale as well as Notre-Dame-des-Victoires Church, levelling everything but a few stone walls and some interior and exterior architectural elements, some of which can still be seen today. Archaeological and restoration work done on the houses starting in the 1960s uncovered numerous traces of the conflict, including bomb fragments and cannonballs. Excavations conducted on vaulted cellars where merchants’ goods were stored and on old latrines from houses in Place-Royale revealed invaluable details about the daily life of merchants and craftsmen. Some of the objects found, such as bottles of wine, fine china, and French earthenware plates and containers, suggest residents had a relatively high standard of living.

After the Conquest, Place-Royale had to be rebuilt quickly because it was an essential centre of economic activity for the entire Quebec City region. It was also home to many key players in social and economic life, such as notables and merchants. The craftsmen involved in the reconstruction efforts—master masons, carpenters, joiners, and architects— were francophones who drew from French tradition to revive the neighbourhood. So until the mid-19th century, the architectural features of the homes in Place-Royale reflected the constraints of the confined urban environment and the traditional know-how of craftsmen of French descent rather than any particular British influence.

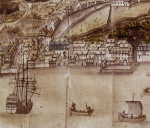

The new buildings were made of stone with gabled plank roofs and parged walls. They were often four stories tall. The tight quarters remained an issue despite the redevelopment of the river banks and wharfs that helped increase the commercial and residential space along the river. The size of the homes and the choice materials testified to the wealth of the Place-Royale merchants. In other parts of town, homes were generally modest, one-story wooden dwellings. The commercial function of Place-Royale was visible in the architecture of the homes, many of which had vaulted cellars and dormer hoists that were used to raise goods up from street level using a rope and pulley system so they could be stored in the attic (NOTE 9).

While British architecture had little influence on the appearance of Place-Royale’s buildings, British culture—spread mainly by the English merchants who outnumbered francophones in Quebec City at the turn of the 19th century—did have an impact (NOTE 10). Archaeological excavations turned up many pieces of British-made crockery, such as creamware, which was strong and relatively inexpensive; jasperware; and stone china, an imitation of Chinese porcelain. Other objects revealed typically English eating habits, such as drinking tea.

Timber-Based Trade

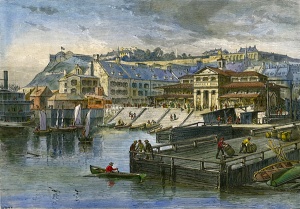

Throughout the 19th century, activities in the Port of Quebec centred on timber exports to Great Britain (NOTE 11). Due to the high demand for wood, which also drove growth of wooden shipbuilding, business was not very diversified in Quebec City, and industries and manufacturing enterprises were rare in the Place-Royale district. Merchants imported goods to provide manufactured products to the people of Quebec City (NOTE 12) and traders and merchants in Place-Royale modified the ground floors and façades of their homes to hang signs, install window displays, and set up shops. As there was little space, some property owners expanded upwards, adding extra floors and covering their buildings in brick—a typically British material—to harmonize their appearance (NOTE 13). In the late 19th century, the face of Place-Royale gradually changed, progressively losing its Ancien Régime French features.

In the 1830s, unhealthy conditions in Place-Royale and a widespread cholera epidemic prompted some merchants and property owners to move to Upper Town. From that point forward, the district was home to mostly shopkeepers and tenants, most of whom were port workers or Irish immigrants fleeing the famine raging in Ireland. Businesses and warehouses replaced homes. Attracted by the uptick in business, financial institutions— banks, insurance companies, and even the Quebec Stock Exchange—set up near Place-Royale on Rue Saint-Pierre, further consolidating the district’s role as the city’s economic centre. However, this situation was not to last.

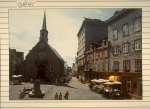

Due to competition from the Port of Montreal, the booming iron market, and the expanding railroad network, port activity in Quebec City, which was still centred around the timber trade, began to decline in the early 1860s (NOTE 14). The Place-Royale market, with its close links to the port, soon followed suit. Businesses moved out. In 1860, an imposing stone building housing the Champlain Market was opened. This covered market, built on reclaimed land in the former Cul-de-Sac port, a stone’s throw from Place-Royale, superseded once and for all what had for over 200 years been the main market in Quebec City. In 1895, a fountain was installed in the centre of Place-Royale, marking its transformation into a simple public square.

One Last Reprieve

In the early decades of the 20th century, the development of the tourist industry made Place-Royale a prime location for hotels and restaurants. The conversion of certain homes that had maintained their French features led to architectural changes that left them with a more contemporary appearance (NOTE 15). With access to the area improved by tramway service, port workers deserted Place-Royale for the nearby suburbs, leaving the district’s rental properties to gradually fall into disrepair (NOTE 16).

Now a neighbourhood for poor families and renters rather than homeowners, Place-Royale fell into decline, blight spread, and the district grew increasingly rundown. Between 1900 and 1950, renovations to some buildings further erased the last remaining traces of the French Regime. By the mid-20th century, Place-Royale had become so dilapidated that an ambitious revitalisation plan was developed. The plan, carried out in the 1970s and 1980s, sought to evoke Place-Royale’s French origins.

Discovering Place-Royale Today

The birthplace of urban architecture in Quebec City, Place-Royale is a historic and archaeological site unique in North America. After years of decline and neglect beginning in the late 19th century, the district required major work, which began in the 1960s. These efforts restored the square’s French Regime architectural aesthetic. In addition to comprehensive reconstruction work, archaeological excavations turned up numerous artefacts bearing witness to the European occupation of the site. Countless pieces and fragments were found, and nearly 14,000 objects reconstructed. This extensive collection of artefacts is an indispensable reference for researchers, and gave rise to extensive documentary research. Numerous scientific reports interpreting these artefacts were published between the 1970s and 1990 by Québec’s Ministère de la culture in the series entitled Dossiers: Collection Patrimoine, published by Les Publications du Québec (NOTE 17). In addition, a generously illustrated 1998 work geared toward the general public, Trésors et secrets de Place-Royale, documents some 200 pieces from the collection.

Today visitors can see some of these artefacts at the Centre d’interprétation de Place-Royale. Opened in 1999, the Centre is located in Place-Royale on the site of two historic homes, of which significant vestiges still remain (NOTE 18). Material and intangible heritage is showcased here through permanent exhibitions featuring a model of the architectural transformations of the homes over the centuries, artefacts illustrating life under the French Regime and the presence of Amerindians dating to nearly 3,000 years BCE, as well as reproductions of Quebec building interiors from the 17th through the 19th centuries. The Centre also holds events with actors playing the roles of historic figures and tradespeople. The Centre also shows a 3D film on the adventures of Samuel de Champlain. Through these museum displays and new communication technologies, the Centre d’interprétation de Place-Royale gives the public access to a rich collection of artefacts that provides a window onto the life and times of the people who called this place home over the centuries.

Sébastien Couvrette

Historian, Université Laval

Additional DocumentsSome documents require an additional plugin to be consulted

Images

-

Animation historique

Animation historique

à Place-Royale,... -

Assiette de céramique

Assiette de céramique

(Régime frança... -

Basse-ville de Québec

Basse-ville de Québec

et le London C... -

Biface de pierre du s

Biface de pierre du s

ylvicole moyen ...

-

Billes découvertes à

Billes découvertes à

la Maison Filio... -

Bol à punch (entre 17

Bol à punch (entre 17

50 et 1775) déc... -

Bouteille de vin (ent

Bouteille de vin (ent

re 1699 et 1750... -

Buste de Louis XIV à

Buste de Louis XIV à

Place-Royale en...

-

Buste de Louis XIV au

Buste de Louis XIV au

centre de Plac... -

Cafetière (entre 1761

Cafetière (entre 1761

et 1810) décou... -

Carte de l'Amérique

Carte de l'Amérique

septentrionale ... -

Centre d'interprétati

Centre d'interprétati

on de la Place ...

-

Champlain supervise l

Champlain supervise l

a construction ... -

Chaudron de cuivre (e

Chaudron de cuivre (e

ntre 1645 et 16... -

Commode de pin et d'é

Commode de pin et d'é

rable galbée à ... -

Détail d'une carte mo

Détail d'une carte mo

ntrant Québec e...

-

Détail de la maquette

Détail de la maquette

de Michel Berg... -

Divers récipients à c

Divers récipients à c

ondiments décou... -

Ensemble de bâtiments

Ensemble de bâtiments

de Place-Royal... -

Entrée de serrure et

Entrée de serrure et

clé (entre 1753...

-

Escalier de sauvetage

Escalier de sauvetage

en maille de f... -

Espace découverte pou

Espace découverte pou

r les jeunes au... -

Espace découverte pou

Espace découverte pou

r les jeunes au... -

Espace découverte pou

Espace découverte pou

r les jeunes au...

-

Façade de l'hôtel Lou

Façade de l'hôtel Lou

is XIV, Place R... -

Fêtes de la Nouvelle

Fêtes de la Nouvelle

-France à Place... -

Fragment de papier pe

Fragment de papier pe

int (vers 1905)... -

Hôtel Blanchard à Pl

Hôtel Blanchard à Pl

ace Royale vers...

-

Hôtel Blanchard à Pla

Hôtel Blanchard à Pla

ce-Royale près ... -

Hôtel Blanchard à Pla

Hôtel Blanchard à Pla

ce-Royale, vue ... -

L'une des maisons de

L'une des maisons de

Place-Royale, 2... -

L'une des vitrines th

L'une des vitrines th

ématiques du Ce...

-

La «chambre à coucher

La «chambre à coucher

de Jean Talon»... -

La «chambre à coucher

La «chambre à coucher

de Jean Talon»... -

La «salle du Conseil»

La «salle du Conseil»

ou salle à dîn... -

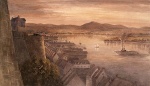

La basse-ville de Qué

La basse-ville de Qué

bec vue de la t...

-

La basse-ville de Qué

La basse-ville de Qué

bec, 1778 -

La Maison Barbel à Pl

La Maison Barbel à Pl

ace-Royale en 2... -

La Maison Barbel avan

La Maison Barbel avan

t (en 1970) et ... -

La Maison Barbel avan

La Maison Barbel avan

t les travaux d...

-

La Maison Leber avant

La Maison Leber avant

les travaux de... -

Le marché de la basse

Le marché de la basse

-ville de Québe... -

Le vieux magasin du R

Le vieux magasin du R

oi tel qu'il ap... -

Les Maisons le Picart

Les Maisons le Picart

(1763) et Dumo...

-

Maquette présentant l

Maquette présentant l

'intérieur d'un... -

Marché de la basse-vi

Marché de la basse-vi

lle de Québec e... -

Marché de la basse-vi

Marché de la basse-vi

lle de Québec e... -

Monnaie de carte

Monnaie de carte

-

Montage présentant l'

Montage présentant l'

entreprise de r... -

Pichet à bière en grè

Pichet à bière en grè

s rhénan -

Place Royale pendant

Place Royale pendant

le Carnaval d'h... -

Place Royale, à Québe

Place Royale, à Québe

c

-

Place-Royale en 1650

Place-Royale en 1650

-

Place-Royale en 1759

Place-Royale en 1759

-

Place-Royale en 1850

Place-Royale en 1850

-

Québec: le marché Fin

Québec: le marché Fin

lay et ses quai...

-

Quelques artefacts li

Quelques artefacts li

és à l'alimenta... -

Vaisselle de porcelai

Vaisselle de porcelai

ne découverte à... -

Vue de l'église de No

Vue de l'église de No

tre-Dame-des-Vi... -

Vue de la citadelle à

Vue de la citadelle à

Québec le soir...

Hyperliens

Catégories

Notes

1. Sauf indication contraire, le terme de Place-Royale désigne, dans le présent article, l’ensemble des édifices qui entourent la place où s’élève l’église Notre-Dame-des-Victoires. Le secteur de la Place-Royale, quant à lui, englobe les rues avoisinantes et correspond à ce qui est identifié comme étant le quartier Place-Royale.

2. Les plus anciens objets découverts à la Place-Royale – parmi lesquels des morceaux de poterie, des outils de pierre et même une fosse funéraire – appartiennent à la culture amérindienne et indiquent une série d’occupations intermittentes qui remontent à plus de 2 000 ans avant l’arrivée de Samuel de Champlain. Les vestiges les plus anciens trouvés dans le secteur de la pointe de Québec témoignent d’une présence amérindienne remontant à près de 3 000 ans avant notre ère. Norman Clermont, Claude Chapdelaine et Jacques Guimont, L’occupation historique et préhistorique de la place royale, Québec, Les publications du Québec, 1992.

3. Une partie de ses objets peuvent être visualisés sur le site Place-Royale, d’aujourd’hui à hier et dans l’ouvrage de Camille Lapointe, Trésors et secrets de Place-Royale. Aperçu de la collection archéologique, Québec, Les Publications du Québec, 1998, p. 3.

4. L’emplacement stratégique de la pointe de Québec avait incité Samuel de Champlain à y faire construire une Habitation en 1608. L’édifice de bois, reconstruit en pierres en 1624, sert notamment de comptoir pour le commerce des fourrures.

5. Ainsi, l’Habitation est fortifiée par différents dispositifs de défense : pont-levis, fossé, plateformes à canon, murailles percées de meurtrières. Françoise Niellon et Marcel Moussette, L’habitation de Champlain, Québec, Les publications du Québec, 1981, p. 29.

6. L’existence de ce premier marché public de la ville de Québec sera officialisée en 1676. Monique La Grenade-Meunier, La société de Place-Royale à l’époque de la Nouvelle-France, Québec, Les Publications du Québec, 1992, p. 415.

7. En plus des marchands et des négociants, les propriétaires de résidences à la Place-Royale sont des artisans de métier, des administrateurs coloniaux ou des individus qui exercent une profession libérale. En ce qui concerne les professions exercées par les femmes sous le Régime français, une étude relève la présence d’une propriétaire-négociante, une aubergiste, une cabaretière et une couturière. Micheline Tremblay, Étude de la population de Place-Royale, 1660-1760, Québec, Les Publications du Québec, 1993, p. 5-6 et 89.

8. En 1661, l’incendie d’une maison avait pu être maîtrisé de justesse. Les premiers règlements seront ensuite promulgués par le Conseil souverain, créé en 1663. Mais il faudra cependant attendre l’arrivée du gouverneur Frontenac en 1672 pour voir l’instauration d’une véritable politique en matière d’urbanisme et de règlementation. Parmi les mesures prises par Frontenac notons la construction de murs pignons en maçonnerie, des échelles sur les toits et l’obligation de faire ramoner régulièrement les cheminées. Robert Côté, Portraits du site et de l’habitat de Place-Royale sous le Régime français : synthèse, Québec, Les Publications du Québec, 1992, p. 18, 30-31 et 64-65.

9. L’actuelle maison Dumont offre une reconstitution d’une lucarne de ce type. Cette technique d’entreposage sera interdite à partir du milieu du XIXesiècle. Laframboise et La Grenade-Meunier, La fonction résidentielle à Place-Royale, 1760-1820…, p. 225. Laframboise, La fonction résidentielle de Place-Royale, 1820-1860…, p. 358.

10. L’influence britannique sur l’architecture de Québec commence à apparaître à la fin du XVIIIe siècle par l’entremise d’ingénieurs de l’armée britannique et d’artisans anglo-saxons, mais ne se répandra que lentement au cours du XIXe siècle. À la Place-Royale, cette influence restera superficielle, portant surtout sur des techniques de construction, et transformant des éléments en façade, car l’immobilier y est déjà en place dès le tournant du XIXe siècle. De plus, dans les premières décennies du XIXe siècle, les rénovations rendues indispensables en raison du vieillissement des habitations sont exécutées par des artisans d’origine française. Laframboise et La Grenade-Meunier, La fonction résidentielle à Place-Royale, 1760-1820, p. 172-174. Yves Laframboise, La fonction résidentielle de Place-Royale, 1820-1860, synthèse, Québec, Les Publications du Québec, 1991, p. 162.

11. En période d’industrialisation, la Grande-Bretagne a grandement besoin de bois et s’approvisionne dans ses colonies, comme le Canada. L’industrie forestière bat son plein dans la partie ouest de la colonie (province de Québec et nord-est de l’Ontario actuels) et le port de Québec devient la plaque tournante du commerce d’exportation du bois vers la métropole.

12. Au tournant du XIXe siècle, quelque 850 personnes habitent dans le secteur de Place-Royale, l’espace saturé a déjà atteint les limites de sa capacité d’accueil; en 1861 ce n’est qu’un peu plus de 1 000 habitants qui y sont recensés. Dans le même laps de temps, la population de la ville de Québec va plus que sextupler, passant de quelque 8 000 à près de 52 000 habitants. Plus de la moitié des résidents de Place-Royale, propriétaires et locataires, occupent des fonctions et des métiers liés au négoce et aux activités portuaires. Les artisans, surtout localisés sur la rue du Petit-Champlain, y sont de moins en moins présents. Ils représentent 22 % de la population du secteur de Place-Royale en 1682, une proportion qui tombe à environ 12 % en 1860. Laframboise et La Grenade-Meunier, La fonction résidentielle à Place-Royale, 1760-1820…, p. 10. Yves Laframboise, La fonction résidentielle de Place-Royale, 1820-1860, p. 12.Côté, Place-Royale…, p. 161.

13. La maison Fornel en est un exemple. Michel Gaumond, « Les vieux murs témoignent » : le Collège des Jésuites, la 1er église de St-Joachim, la MaisonFornel, Québec, Ministère des affaires culturelles, 1978, p. 85. Laframboise, La fonction résidentielle de Place-Royale, 1820-1860…, p. 161-162.

14. Des années 1860 aux années 1880, le nombre de navires qui s’arrêtent au port de Québec diminue rapidement et un même mouvement de décroissance affecte l’industrie de la construction navale et le commerce du bois. Il passe de 1500 bateaux en 1861 à quelque 275 en 1889. Toutefois, les bateaux qui fréquentent le port sont de plus fort tonnage qu’auparavant et transportent donc de plus volumineuses cargaisons. Les modifications apportées aux installations portuaires pour s’adapter à cette nouvelle réalité témoignent d’une certaine vitalité des lieux. Ainsi, le port demeure encore un secteur d’activités relativement important où transitent voyageurs et marchandises qui utilisent également le chemin de fer. Côté, Place-Royale…, p. 167-168.

15. L’hôtel Blanchard, érigé à partir de la maison Le Picart en 1844, en est un exemple. Cet hôtel, qui a été fortement endommagé par un incendie en 1966, avait été agrandi en 1903 avec l’intégration de la maison Dumont. Il a pris par la suite le nom d’hôtel Louis XIV. Jean-Marie Lebel, « Quand le président américain Taft avait sa chambre à Québec », Prestige, février 2010, p. 70-71.

16. Des années 1860 à 1920, le secteur de Place-Royale continue néanmoins d’attirer les milieux d’affaires et les institutions financières de même que les entreprises de presse. Toutefois, à partir des premières décennies du XXe siècle de nombreuses institutions financières iront s’établir en Haute-Ville, suivant le mouvement de la population.

17. Ces rapports sont, pour nombre d’entre eux, disponibles sur le site Nos racines.

18. Il s’agit des maisons Hazeur, construite au XVIIe siècle, et Smith, datant du XIXe siècle.

Bibliographie

Clermont Norman, Claude Chapdelaine et Jacques Guimont, L’occupation historique et préhistorique de la place royale, Québec, Les publications du Québec, 1992.

Côté Renée, Place-Royale : quatre siècles d'histoire, Montréal, Musée de la civilisation, Fides, 2000.

Côté Robert, Portraits du site et de l’habitat de Place-Royale sous le Régime français : synthèse, Québec, Les Publications du Québec, 1992.

Laframboise Yves et Monique La Grenade-Meunier, La fonction résidentielle à Place-Royale, 1760-1820, synthèse, Québec, Les Publications du Québec, 1991.

Laframboise Yves, La fonction résidentielle de Place-Royale, 1820-1860, synthèse, Québec, Les Publications du Québec, 1991.

La Grenade-Meunier Monique, La société de Place-Royale à l’époque de la Nouvelle-France, Québec, Les Publications du Québec, 1992.

Lapointe Camille, Trésors et secrets de Place-Royale. Aperçu de la collection archéologique, Québec, Les Publications du Québec, 1998.

Paulette Claude, Place-Royale. Berceau d’une ville, Québec, Les Publications du Québec, 1986.

Provencher Jean, L’histoire du Vieux-Québec à travers son patrimoine, Québec, Les Publications du Québec, 2007.