The Cathedrals of Saint-Boniface

par Girard, David

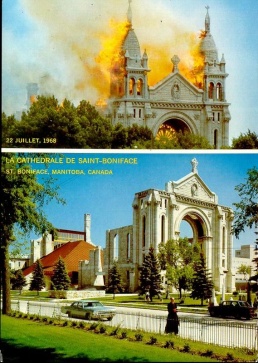

Since 1818, six churches have stood in succession in Saint-Boniface, Manitoba testifying to the longstanding French and Catholic presence in western Canada. The Red River town—now a borough of Winnipeg— grew by leaps and bounds over its first fifty years, from the humble Saint-Boniface Mission to the seat of a vast archdiocese covering most of western Canada. This growth led to the successive construction of five cathedrals. The largest and most prestigious, completed in 1908 under second Archbishop Adélard Langevin, was destroyed by fire in 1968, to the dismay of the francophone population for whom it was a symbol of strength. Today’s cathedral, consecrated in 1972, stands within the great edifice’s ruins, preserving the heritage value of a site that strongly symbolizes the francophone presence in western Canada.

Article disponible en français : Cathédrales de Saint-Boniface

The Starting Point of Francophone Settlement in the Prairies

A landmark of the Franco-Manitoban community, Saint-Boniface Cathedral marks the site of the Prairies’ first French Catholic settlement and the starting point of francophone expansion in the west. Built at great expense in the early 20th century, this impressive Romanesque Revival cathedral fast became a source of pride for francophones, a testimony to their survival as a cultural minority. The cathedral’s importance was further enhanced when it was consecrated as a minor basilica in 1949, and for many years it was also western Canada’s tallest religious structure. When fire destroyed the cathedral in 1968, it left the community in shock. When the time came to design a new cathedral in the early 1970s, architect Étienne Gaboury placed it within the ruins of the old one out of sensitivity to the site’s symbolic resonance. In this way the heritage value of the site, successive home to two churches and four cathedrals, was preserved. Designated a Manitoba Provincial Heritage Site in February 1994, today’s cathedral attracts thousands of visitors each year.

Religious Competition in the West

The story begins in 1817, at the height of the fur trade, when 22 Red River settlers petitioned for a resident priest. Monsignor Joseph-Octave Plessis, Archbishop of Quebec City, sent Joseph-Norbert Provencher, a unilingual francophone, to head up a small mission the following year. Upon arrival Provencher oversaw the construction of a small building to double as his residence and the Red River Mission’s first chapel (NOTE 1). On November 1, 1818 the site was consecrated as Saint-Boniface (NOTE 2). In 1919 construction began on a new church. Lord Selkirk, who had already granted land for the mission (NOTE 3) and established a Scottish Catholic community in the area, contributed a newly cast bell from England. A lack of funds delayed completion of the new church until 1825.

Establishing the mission was no simple matter. Even before sending Provencher, Plessis knew he couldn’t administer the Red River settlement from Quebec City: a western Canadian diocese would be necessary. Despite the settlement’s youth and small population he quickly took steps in this direction, anxious to reach his goal before the Anglicans (NOTE 4) or the English-speaking Irish and Scottish Catholics, who already outnumbered local francophone Catholics (NOTE 5). Plessis even contacted London and the Vatican for permission to name Provencher an auxiliary Bishop of the Quebec City Archdiocese, as well as vicar general. On May 12, 1882, after three years of efforts and initial resistance from Provencher, Plessis finally sealed the appointment.

From Auxiliary Diocese to Archdiocese

In light of the mission’s new status as auxiliary diocese and the growing francophone population, it was decided to build a new and larger cathedral (NOTE 6). The ambitious structure known as “Provencher’s cathedral” (NOTE 7) was erected between 1832 and 1839. Its imposing size made it popular with visiting artists who have left behind a number of drawings and paintings. American poet John Greenleaf Whittier (1807–1892) added to the structure’s renown with his poem, “The Red River Voyageur,” published with an illustration of the cathedral (NOTE 8).

On a visit to Quebec City in 1843, Joseph-Norbert Provencher convinced Archbishop Joseph Signay to make Red River an independent ecclesiastical district. The Vatican approved the plan on April 16, 1844 and Provencher was named Vicar Apostolic of Hudson Bay and James Bay (NOTE 9). Two years later, following the establishment of an ecclesiastical province on the Pacific coast, Signay suggested making the Red River District an archdiocese. When Provencher demurred, Signay settled on creating a diocese on June 4, 1847. Three years later the North-West Diocese was renamed the Diocese of Saint-Boniface.

On March 25, 1857, Louis Riel received first communion in Provencher’s cathedral. Three years later, on December 14, 1860, the building burned to the ground. Alexandre-Antonin Taché, Bishop of Saint-Boniface since 1853, set off for Quebec City to raise money to rebuild. Construction of Taché’s cathedral began in 1862 and was completed in 1863. Built on a tighter budget, it was smaller than its predecessor and plans for façade towers and frontal ornamentation were abandoned. The bell tower was not completed until 1870. Bishop Taché was now ready to go along with the Archbishop of Quebec’s wishes: the cathedral became the seat of the Archdiocese of Saint-Boniface on September 22, 1871. The funeral of Louis Riel, hanged in Regina for treason, was held there in 1885.

Saint-Boniface Gets a Minor Basilica

The late 19th century was difficult for Franco-Manitobans. French lost its status as Manitoba’s second official language and confessional schools were abolished in 1890 (NOTE 10). The franchophone community along the Red River felt threatened and took steps to incorporate Saint-Boniface as a city to better preserve its francophone character and stave off amalgamation with Winnipeg. This project met with success in 1908.

That same year saw the inauguration of an impressive new cathedral. The pride and joy of the community, it was known as “Langevin’s cathedral” in honour of Archbishop Adélard Langevin, who had begun raising funds for its construction in 1904. In 1906 Langevin stated that “this new building is a necessity: our children alone fill the current cathedral” (NOTE 11). Indeed, the population was climbing steadily: according to 1907 statistics published in Les Cloches de Saint-Boniface (NOTE 12), the archdiocese’s ecclesiastical newsletter, the number of Catholics in western Canada had shot from 12,000 in 1881 to 20,000 in 1888. Saint-Boniface itself had gone from 2,154 Catholics in 1888 to 4,615— almost all francophone—in January 1906. This twofold increase in Saint-Boniface’s Catholic population spurred the creation of new parishes. And the fact that the cathedral was the seat of the Archdiocese of Saint-Boniface, the highest catholic authority in western Canada, made the need for a new building all the more pressing.

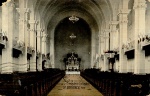

Construction cost $200,000 (not counting the interior), a sum borrowed over a 40 year term in 1906. The building, a blend of Roman and Byzantine influences, was the largest religious structure in the west and quickly became a source of great pride to for francophones throughout the region after it opened in 1908. As for Taché’s cathedral, which had fallen into disrepair and was considered unsafe, it was torn down the following year. The new cathedral was decreed a minor basilica by Pope Pius XII on June 10, 1949, because its form echoes certain Roman basilicas (except for the cupola and transepts which were never built) (NOTE 13).

The 1968 Fire and Reconstruction

On July 22, 1968, mere days after the 150th anniversary of the Saint-Boniface mission, a devastating fire broke out during interior renovations. Onlookers watched in horror as the building burned to the ground in two short hours. The wooden bell tower and plaster-encased wooden pillars offered little resistance to the flames; only the stone walls survived. Faced with the destruction of a monument so dear to francophone Catholics, elderly nuns declared the fire a loss not only for Saint-Boniface but for country as a whole. They felt that this lost link to the region’s history would leave a great void and impoverish the community (NOTE 14). Philippe Mailhot, director of the Saint-Boniface Museum and an eyewitness to the fire, relates that “the day of the fire was truly sad, especially when the bells fell. A great cry went up from the crowd and we all felt that we were witnessing the end of something. It only took three hours, and at the end of the day only the stone walls were left. I’ve never seen such a terrible fire (NOTE 15).” A mainstay of Franco-Manitoban heritage was lost.

But the people of Saint-Boniface were not to be deterred. Led by Archbishop Maurice Baudoux, in office since 1955, they started taking steps to build a fourth cathedral. The symbolic importance of the structure was such that parishioners were willing to go into debt for 25 years to rebuild the cathedral in its predecessor’s image. However, initial estimates of over $10 million indicated that the cost of such a project would be prohibitively expensive. With church attendance falling and Vatican II reforms ushering in a period of uncertainty, Mgr. Baudoux (NOTE 16) opted for a less costly design. Franco-Manitoban architect Étienne Gaboury was awarded the contract on a $630,000 shoestring budget. He was determined to set the new place of worship within the ruins of the renowned cathedral to maintain an unbroken link to this deeply significant site. Opened in 1972, his resolutely modern structure was only half as large as Langevin’s cathedral. It held 1,000 people: fewer than its predecessor’s 2,500 but enough for the number of parishioners who regularly attended mass at that time.

A Place of Great Meaning

Even if the minor basilica is no longer with us, the people of Saint-Boniface and visitors alike appreciate the way Gaboury’s church fits within the preserved walls of the burned cathedral. The succession of six Catholic churches over close to 200 years on a single spot has created a site of great heritage value and significance for the francophones of the Canadian Prairies. The Saint-Boniface Cathedral still stands today as a vibrant and powerful symbol of the deep-rooted francophone presence in the west and the community’s determination to keep its culture alive and flourishing.

David Girard

Historian

Université Laval

NOTES

1. The small bell of this modest chapel can be seen at the Saint-Boniface Museum, and still works today.

2. In honour of Saint-Boniface, Apostle of Germany, an important missionary who became an archbishop after converting numerous pagans.

3. Lord Selkirk granted two concessions: first, twenty acres along the Assiniboine River to the east of the Red River, then close to 15,000 acres to the east of the Seine River. This second tract of land shares the approximate boundaries of the City of Saint-Boniface, incorporated in 1908.

4. John West, an Anglican minister, arrived in 1820 and built the first Anglican church in 1823. It also became a cathedral.

5. Lemieux, Lucien, “Provencher, Joseph-Norbert,” in Dictionary of Canadian Biography Online, consulted 11/02/11 [online], http://www.biographi.ca/009004-119.01-e.php?BioId=38265.

6. The 1819 church became a cathedral when it was made the seat of an auxiliary bishop (under the authority of the Archdiocese of Quebec) in 1822..

7. The Saint-Boniface Museum houses a scale model that affords a glimpse of what this impressive Cathedral must have looked like at the time.

8. Whittier, John Greenleaf, The Red River Voyageur. Hudson Bay Co.: 1892, p. 8.

9. The territory of the vicariate, diocese, and later archdiocese was immense: 1.79 million square miles encompassing the entire Arctic Basin and all of Rupert’s Land.

10. Two laws were passed in 1890. The Official Language Act made English the official language of government and the courts. But it was the second law abolishing confessional schools that mobilized the clergy and the French-Canadian elites and sparked the crisis known as the Manitoba Schools Question.

11. “Notre nouvelle cathédrale” in Les Cloches de Saint-Boniface, vol. 5, no. 3, February 1 1906, p. 25. This article also presented the plans for the future cathedral that would begin construction a few months later.

12. Published from 1902 to 1984.

13. It is important not to read the word “minor” in a pejorative sense, as the title of “minor basilica” is an extremely rare designation. The Vatican bestows this honour on religious buildings that recreate multiple elements of the original basilica, the first known church in Christendom still widely held up as an ideal design. These formal aspects are what led Saint-Boniface Cathedral to be decreed a minor basilica. Its Romanesque Revival style recalls the first Christian churches but the lack of transepts and cupola, essential basilica elements, prevent it from attaining full basilica status.

14. Roy, Marie Anna, Les visages du vieux Saint-Boniface: n.d., n.p., 1970, p. 161.

15. Interview by Martin Fournier with Philippe Mailhot, director of the Saint-Boniface Museum, on November 17, 2010.

16. Baudoux was an important Canadian participant in Vatican II and an enthusiastic supporter of the new liturgy. He also strived hard to convince Canadian bishops to work together.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Aubin, Léonce, « La ville cathédrale de Saint-Boniface », dans André Fauchon et Carol J. Harvey (dir.), Saint-Boniface, 1908-2008 : reflets d’une ville, Winnipeg, Presses universitaires de Saint-Boniface, 2008, p. 75-79.

Dauphinais, Luc, Histoire de Saint-Boniface, vol. 1 : À l’ombre des cathédrales : des origines de la colonie jusqu’en 1870, Saint-Boniface, Éditions du Blé, 1991, 335 p.

Fournier, Martin, Entrevue avec Philippe Mailhot, directeur du Musée de Saint-Boniface [support numérique], Winnipeg, 17 novembre 2010.

Fournier, Martin, Entrevue avec Étienne Gaboury, architecte [support numérique], Winnipeg, 20 novembre 2010.

Hamelin, Jean, « Taché, Alexandre-Antonin », Dictionnaire biographique du Canada en ligne [en ligne], http://www.biographi.ca/009004-119.01-f.php?&id_nbr=6453, consulté le 11 février 2011.

« La cathédrale et la vieille légende des millions de l’archevêché », Les Cloches de Saint-Boniface, vol. IV, no 20, 1er décembre 1905, p. 306-307.

Lemieux, Lucien, « Provencher, Joseph-Norbert », Dictionnaire biographique du Canada en ligne [en ligne], http://www.biographi.ca/009004-119.01-f.php?&id_nbr=4143, consulté le 11 février 2011.

« Notre nouvelle cathédrale », Les Cloches de Saint-Boniface, vol. V, no 3, 1er février 1906, p. 25-28.

Perin, Roberto, « Langevin, Adélard », Dictionnaire biographique du Canada en ligne [en ligne], http://www.biographi.ca/009004-119.01-f.php?&id_nbr=7510, consulté le 11 février 2011.

Robillard, Denise, Maurice Baudoux (1902-1988), une grande figure de l’Église et de la société dans l’Ouest canadien, Québec, Presses de l’Université Laval, 2009, 518 p.

Roy, Marie-Anna A., Les visages du vieux Saint-Boniface, s. l., s. n., 1970, 167 p.

Société historique de Saint-Boniface, Centre du patrimoine, « Histoire chronologique du diocèse de Saint-Boniface », Au pays de Riel [en ligne], http://shsb.mb.ca/node/386, consulté le 11 février 2011.

« Statistiques catholiques », Les Cloches de Saint-Boniface, vol. VI, no 4, 15 février 1907, p. 50-52.

Whittier, John Greenleaf, The Red River Voyageur, Hudson Bay Co., 1892, 17 p.

Additional DocumentsSome documents require an additional plugin to be consulted

Images

-

Carte postale montran

Carte postale montran

t l'intérieur d... -

Carte postale montran

Carte postale montran

t la Cathédrale... -

Carte postale montran

Carte postale montran

t la Cathédrale... -

Carte postale montran

Carte postale montran

t la Cathédrale...

-

Carte postale montran

Carte postale montran

t la Cathédrale... -

Carte postale montran

Carte postale montran

t les deux cath... -

Cathédrale de Saint-B

Cathédrale de Saint-B

oniface -

Cathédrale de Saint-B

Cathédrale de Saint-B

oniface sous l'...

-

Cathédrale de Saint-B

Cathédrale de Saint-B

oniface, 2010 -

Cathédrale de Saint-B

Cathédrale de Saint-B

oniface, 2010 -

Cathédrale de Saint-B

Cathédrale de Saint-B

oniface, ca. 19... -

Cathédrale de Saint-B

Cathédrale de Saint-B

oniface, Souven...

-

Cathédrale de St-Boni

Cathédrale de St-Boni

face et couvent... -

Cathédrale en 1858, p

Cathédrale en 1858, p

ar William Napi... -

Cathédrale vue en con

Cathédrale vue en con

tre-plongée -

Cimetière jouxtant la

Cimetière jouxtant la

cathédrale de ...

-

Cimetière jouxtant la

Cimetière jouxtant la

cathédrale de ... -

Esquisse du premier C

Esquisse du premier C

ollège de Saint... -

Extrait du poème The

Extrait du poème The

Red River Voyag... -

Incendie de la cathéd

Incendie de la cathéd

rale en 1968

-

L’intérieur de la qua

L’intérieur de la qua

trième cathédra... -

La cathédrale de Sai

La cathédrale de Sai

nt-Boniface, 18... -

La deuxième cathédral

La deuxième cathédral

e de Saint-Boni... -

La rivière rouge et S

La rivière rouge et S

aint-Boniface v...

-

La troisième cathédra

La troisième cathédra

le (1908-1968)... -

Lever de soleil sur l

Lever de soleil sur l

a vieille cathé... -

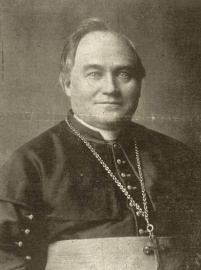

Mgr Langevin qui sera

Mgr Langevin qui sera

sacré archeve... -

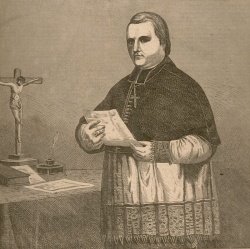

Mgr Provencher

Mgr Provencher

-

Mgr Taché

Mgr Taché

-

Mgr. Alexandre A. Tac

Mgr. Alexandre A. Tac

hé, évêque de S... -

Mgr. Norbert Joseph P

Mgr. Norbert Joseph P

rovencher, 1905 -

Monseigneur Joseph Oc

Monseigneur Joseph Oc

tave Plessis

-

Monument au père Jean

Monument au père Jean

-Pierre Aulneau... -

Monument au père Jean

Monument au père Jean

-Pierre Aulneau... -

Peinture de la cathéd

Peinture de la cathéd

rale (1836-1860... -

Pierre tombale de Lou

Pierre tombale de Lou

is Riel à côté ...

-

Plan de la Basilique

Plan de la Basilique

mineure de Lang... -

Portail de la cathédr

Portail de la cathédr

ale de Saint-Bo... -

Rue Principale de Win

Rue Principale de Win

nipeg; St. Boni... -

Sa grandeur Mgr Tache

Sa grandeur Mgr Tache

́, archevêque ...

-

Saint-Boniface (Manit

Saint-Boniface (Manit

oba) : funérai... -

Saint-Boniface (Manit

Saint-Boniface (Manit

oba) : groupe d... -

Souvenir du sacre de

Souvenir du sacre de

Mgr Bruchési, a... -

Vue de l'église catho

Vue de l'église catho

lique, colonie ...