Calvaire Hill at Oka

par Piédalue, Gilles

Calvaire Hill at Oka is an important heritage site that is not very well known today. It is located in the heart of Parc national d’Oka, west of Montreal Island. Construction of this Way of the Cross goes back to the 1740s, when New France was at its height. It takes the form of a forest path leading to three chapels perched at the top, with four oratories at intervals along the path. Originally missionaries used it to teach Amerindian converts the stages of the Passion of Christ. In the 19th century, the Calvaire d’Oka became one of Quebec’s most important pilgrimage sites. Since 1974, park authorities have sought to protect the unique character of this site and to enhance this jewel of religious architecture dating from New France.

Article disponible en français : Colline du Calvaire d’Oka

The Calvaire d’Oka and its visitors over the years

The practice of the Way of the Cross goes back to the great medieval pilgrimages to Palestine. The Church at that time granted indulgences to pilgrims who went to Jerusalem to follow in the footsteps of Christ to Calvary. The Franciscans began to reproduce this Way of the Cross in their churches. It consisted of seven stations, as at Oka, where the stations are placed at intervals along the winding path leading to the top of a hill which evokes Golgotha, where Jesus was crucified.

The Way of the Cross became popular in New France thanks to the Sulpician order, many of whose members came from Brittany, where devotion to the practice was widespread. Between 1740 and 1742, the Breton Sulpician Hamon Le Guen had this Way of the Cross built not far from Lac des Deux Montagnes, to teach the Passion of Christ to Amerindians.

As the neighbouring parishes developed, settlers of European origin gradually succeeded the Amerindians in the annual pilgrimages to the Calvaire d’Oka. At the end of the 19th century, development of railroads and steamships made it one of Quebec’s most frequented pilgrimage sites. Its popularity later declined until the 1950s. Then, with the sharp drop in religious practice in Quebec, the site quickly lost its attraction for the public. Today, Parc national d’Oka is responsible for the preservation and enhancement of the site, which also offers outdoor enthusiasts a unique heritage walking trail.

History of the Oka pilgrimages

In 1676 the Kentaké mission, located on the south shore of Montreal Island, was a centre for a number of different Amerindian nations from the region: Huron, Mohawk, Oneida, Algonquin and Nipissing (NOTE 1). From this nucleus came the Amerindians of the missions that were later founded near Ville-Marie, including the one at Lac des Deux Montagnes, which the Sulpicians established at the confluence of the river of that name and the Ottawa River. According to the Sulpicians the site, easy to defend and located on the fur trade route, would attract more Amerindians. The Sulpicians built houses, a church, two schools, and a fort.

Around 1750 this mission had a population of 750, mostly Amerindians. To the west of the fort, Mohawks and Hurons, sedentary agricultural nations speaking languages of the Iroquoian family, lived together. To the east of the fort, Nipissings and Algonquins, nations of nomadic hunters speaking Algonquian languages, each had their own grounds. The garrison’s missionaries occupied the small fort located at the centre of the mission. A few nuns, some officials, and settlers of European origin also lived at the mission.

The feast of the Exaltation of the Holy Cross, 14 September, was an important event at the Deux Montagnes mission. This feast day commemorates the return to Jerusalem of the Holy Cross, which had been taken back from the Persians in 626. The feast occurs near the autumn equinox, and marks the end of the harvest. The event also gave the Amerindians a pause before they left for the winter hunt. The Sulpicians took advantage of the opportunity to organize great ceremonies at the Calvaire d’Oka. It was a special occasion for Amerindians to meet until the 1870s, at which time many of them joined the Protestant religion.

During the 19th century, farmers from the neighbouring parishes gradually replaced Ameridians in the annual pilgrimages to the Calvaire. Around 1830 they began to visit the site together with the Amerindians (NOTE 2). From 1850 on, more people from Montreal joined the worshipers. At that time, Oka became the most popular pilgrimage site in the greater Montreal region. At the same time in Europe, the miraculous apparitions at Paris (1830), Notre-Dame de la Salette (1846), and Lourdes (1858) renewed interest in pilgrimages in Quebec as well as in Europe. Visits to the Sanctuary of Sainte-Anne-de-Beaupré increased, and new pilgrimage sites appeared: Notre-Dame-de-Lourdes at Rigaud in 1874, Cap de la Madeleine in 1888, and the Huberdeau grotto in 1892 (NOTE 3).

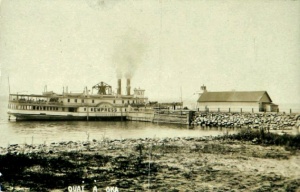

From 1872, the Sulpicians of the Notre-Dame de Montréal parish encouraged their parishioners to go to Oka for the Way of the Cross. Thanks to the development of railroads and steamboats at the end of the 19th century, Oka became one of the most popular pilgrimage sites in Quebec. In the 1880s and 1890s, there were even two Calvaire festivals. The first was held on 14 September for people who came by steamboat; the second took place the following Sunday for local people.

In 1889 the newspapers reported on a crowd estimated at 30,000 (NOTE 4). The pilgrims from Notre-Dame de Montréal took the train at Bonaventure station about 8:00 a.m. When they arrived at Lachine, a steamboat of the Ottawa River Navigation Company took them to the dock at Oka, where they disembarked at 10:00. The return was set for 3:00 p.m. In the meantime, the pilgrims went to the parish church, singing and praying. Indulgences were granted to those who confessed, took communion, and prayed for the Pope on this occasion. The pilgrims then followed the Chemin de l’Annonciation. Turning off to the right at the barrier of the cross, they gathered at the “Orée” at the foot of a large red cross before beginning the climb. There, on a small platform, a preacher addressed the crowd. After crossing the Calvaire farm, the pilgrims followed a rocky trail for a six-kilometre round trip. While walking and at the stops at stations, they sang and prayed. On the way back, they stopped again at the village church to venerate a relic of the True Cross. Later it became customary to perform this ceremony at the hilltop.

In the 20th century, the route followed by the procession between the church and the first oratory changed slightly. However, between the first oratory and the chapels at the top, the path has remained the same since the beginning. From the turn of the century the crowds at Oka became smaller, although pilgrimages remained popular in Quebec for the first half of the 20th century. In 1948 there were still 5,000 pilgrims at Oka for the Calvaire festival. In the 1960s only a few hundred people took part in the pilgrimage. Then, as at most pilgrimage sites in Quebec, participation dropped sharply. The growth of outdoor activities and cultural tourism, however, has kept the Calvaire d’Oka site alive in collective memory. Today the pilgrimage still draws a few worshipers, especially on the Sunday nearest to 14 September.

Integration with Parc national d’Oka; conservation and enhancement of the site

In 1936 the Sulpicians sold their seigneurie to the Compagnie Immobilière Belgo-Canadienne, but continued to serve the Annonciation d’Oka parish. This transaction included Calvaire Hill. In 1939 and 1942, the Sulpicians had to sell land and borrow from the government of Quebec to pay some debts. The loan was repaid in 1962 by the purchase of a small 1.6-square-kilometre parcel of land by the government of Quebec. This land, at first called Réserve de chasse et de pêche de Deux Montagnes (Deux Montagnes hunting and fishing reserve), was renamed Parc provincial d’Oka the following year. In 1968 it took the name Parc Paul-Sauvé, in honour of the deputy from the county of Deux Montagnes who had been premier of Quebec in 1959-60.

The infrastructure of the beach and campground at Parc Paul-Sauvé were soon insufficient to meet the demand for outdoor activities. In 1974 the government of Quebec acquired the areas of Calvaire, Masson Hill and Grande Baie, bringing the area of the park to 23.7 square kilometres (NOTE 5). In the same year, Calvaire hill was classified by the government of Quebec as a historic district; the year before, the bas-reliefs of the oratories and chapels had been designated cultural property.

These decisions came at the right moment, for the buildings were in poor condition and had been damaged by vandals in 1970. Two bas-reliefs had also been seriously damaged. The sculptures were removed from the oratories and placed safely in the parish church. The bas-reliefs, restored in 1978 by the National Gallery of Canada, can be admired at the Kateri Tekakwitha Chapel at the Église de l’Annonciation in Oka. In 1980, the Société Immobilière d’Oka finally ceded the bas-reliefs to the Oka parish council.

The chapels and oratories were also restored in 1978. Interpretive panels were installed at the beginning of the path, and reproductions replaced the original statues in the buildings. The Calvaire d’Oka was classified a historical site in 1982 because of its interest as witness to the conversion of Amerindians in the 17th and 18th centuries and because of its unique character. The heritage value of the site comes also from its ethnological aspect, as it recalls the popularity of pilgrimages in the history of Quebec.

Since 1999 the park administration has completed several stages of enhancement and revitalization of the site. The Société des établissements de plein air du Québec began by producing a report on the best ways to give it new life, including a list of restoration and development needed. As these works were being carried out, copies of the bas-reliefs were made by the sculptor George Vincelli, and installed in the buildings to replace the originals. Now a permanent exhibition is being prepared, to be held in an interpretive centre dedicated to the Calvaire historic site.

A remarkable heritage site

Today, the Calvaire d’Oka trail receives thousand of visitors each year. The site attracts lovers of outdoor activities, nature and history, all of whom find the nature, culture and calm that they seek. In every season visitors can go back in time thanks to this remarkably well-preserved site, which has kept its character from the time of the Saint Lawrence French colony. In the silence of the forest, along the trail that climbs the hill, at the oratories and the Romanesque chapels, and with the panorama visible from the hilltop, everything is conducive to quietness and contemplation. The Calvaire d’Oka hill, besides being an important historic site, is located in a remarkably rich natural environment.

Readers interested in Calvaire d’Oka architecture and art can consult the detailed appendix on these matters.

Gilles Piédalue

Historian

Parc national d’Oka

NOTES

1. Harris, R. Cole, Atlas historique

du Canada, Volume I. Des origines à 1800, Presses de l’Université de

Montréal, 1987, plate 47.

2. Rousseau, Louis; Remiggi, Frank W., Atlas des pratiques religieuses, le sud-ouest du Québec au 19ième

siècle, Presses de l’Université d’Ottawa, 1998, p.124.

3. Lapierre, Guy, “Lieux de pèlerinage au Québec, une vue

d’ensemble”, pp. 29-64, Boglioni, Pierre; Lacroix, Benoît, Les pèlerinages au Québec, Laboratoire d’histoire religieuse,

Université Laval, no. 4, 1981, 160 pages.

4. Porter, John R.; Trudel, Jean, Le calvaire d’Oka, Ottawa, National Gallery of Canada, 1974,

p. 50.

5. Government of Quebec acquisition of Calvaire Hill from the Société

Immobilière d’Oka. After 1990, it was the Parc de récréation d’Oka. The site,

which was classified in 2001 as a national park under the management of the Société

des établissements de plein air du Québec (Sépaq), now bears the name of Parc

national d’Oka.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Cloutier, Nicole, « Calvaire, Oka », dans Québec, Commission des biens culturels, Les chemins de la mémoire, t. II : Monuments et sites historiques du Québec, Québec, Publications du Québec, 1991, p. 403-404.

Drouin, Daniel, « Œuvres d'art des chapelles du calvaire d'Oka », dans Québec, Commission des biens culturels, Les chemins de la mémoire, t. III : Biens mobiliers du Québec, Québec, Publications du Québec, 1999, p. 135-138.

Harris, R. Cole, Atlas historique du Canada, vol. I : Des origines à 1800, Montréal, Presses de l’Université de Montréal, 1987, 198 p.

Laperrière, Guy, « Les lieux de pèlerinage au Québec : une vue d’ensemble », dans Pierre Boglioni et Benoît Lacroix (édit.), Les pèlerinages au Québec, Québec, Presses de l'Université Laval, 1981, p. 29-64.

Porter, John R., et Jean Trudel, Le calvaire d’Oka, Ottawa, Galerie nationale du Canada, 1974, 125 p.

Québec, Ministère de la Culture, des Communications et de la Condition féminine, « Calvaire d'Oka : valeur patrimoniale et information historique », Répertoire du patrimoine culturel du Québec [en ligne], http://www.patrimoine-culturel.gouv.qc.ca/RPCQ/detailBien.do?methode=consulter&bienId=93537.

Rousseau, Louis, et Frank W. Remiggi, Atlas historique des pratiques religieuses : le sud-ouest du Québec au XIXe siècle, Ottawa, Presses de l’Université d’Ottawa, 1998, 235 p.

Additional DocumentsSome documents require an additional plugin to be consulted

Images

-

Bateau à vapeur Empre

Bateau à vapeur Empre

ss accosté au q... -

Détail du portail d'u

Détail du portail d'u

ne chapelle lat... -

Détail du toit à peti

Détail du toit à peti

ts coyaux, chap... -

Fenêtre et mur blanch

Fenêtre et mur blanch

i à la chaux, c...

-

Fenêtre latérale de l

Fenêtre latérale de l

a chapelle prin... -

Fenêtre vue de l'Inté

Fenêtre vue de l'Inté

rieur, chapelle... -

Foule de pèlerins sur

Foule de pèlerins sur

la colline du ... -

Itinéraire du chemin

Itinéraire du chemin

de croix du Cal...

-

La foule de pèlerins

La foule de pèlerins

rassemblé autou... -

La foule de pèlerins

La foule de pèlerins

rassemblée auto... -

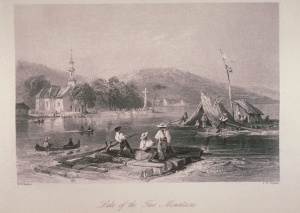

Le lac des Deux Monta

Le lac des Deux Monta

gnes au XIXe si... -

Les trois chapelles d

Les trois chapelles d

u Calvaire au s...

-

Mur du côté ouest, ch

Mur du côté ouest, ch

apelle principa... -

Mur en fruits, intéri

Mur en fruits, intéri

eur de la chape... -

Novembre, mois des mo

Novembre, mois des mo

rts au sommet d... -

Oratoire sur le senti

Oratoire sur le senti

er

-

Passage escarpé du se

Passage escarpé du se

ntier du Calvai... -

Pèlerinage sur la col

Pèlerinage sur la col

line du Calvair... -

Portail de la chapell

Portail de la chapell

e principale -

Sculpture dans l'un d

Sculpture dans l'un d

es oratoires

-

Sobriété du décor, ch

Sobriété du décor, ch

apelle principa... -

Toit de l'un des orat

Toit de l'un des orat

oires -

Tympan de la chapelle

Tympan de la chapelle

principale, av... -

Un oratoire

Un oratoire

Document PDF

Hyperliens

- Répertoire du patrimoine culturel du Québec : fiche du Calvaire d'Oka

- Répertoire du patrimoine culturel du Québec : fiche des oeuvres d'art des chapelles du calvaire d'Oka

- Calvaire d'Oka - statut de bien culturel classé