The Origins of the Acadian Flag and National Holiday: the Memramcook and Miscouche Conventions

par Bourque, Denis

The ten Acadian national conventions—which took place between 1881 and 1937—still hold great significance today for people interested in Acadian cultural identity, history and heritage. These conventions are largely the foundation of what is modern Acadia today. The first two such events are of particular historical significance, since it was in Memramcook (1881) and then in Miscouche (1884), that the Acadians first asserted themselves as a people with a distinct national identity who were to be distinguished from the French Canadians. It was also then that they adopted national symbols which embodied their unique identity, including a patron saint, national holiday, flag and anthem. At the time, the Acadian elite hoped to unite the people around these symbols and rally the collective strength of the nation to engage in the struggle to obtain recognition of their fundamental cultural, political, social and language rights. These historic conventions were events that forged a major part of the Acadian cultural identity into what it is today.

The Origin of Acadian Nationalism

It is worth remembering that it was the second major French Canadian national convention—organised in 1880 by the Saint-Jean-Baptiste Society in Quebec City—that inspired Acadians to hold their own national convention (NOTE 1). In his introduction to Conventions Nationales des Acadiens, Pascal Poirier mentions that around a hundred representatives were chosen “from all over, from every parish and every town in Acadia” to participate in the convention where they would have the privilege of sitting on the seventh Committee (NOTE 2). For the first time, Acadians that had been scattered throughout various provinces could come together to “s'émoyer,” or in other words, to exchange stories and share about their lives (NOTE 3). Pascal Poirer writes that “before the convention in Quebec City, Acadia was scattered around the country, but the delegates left the event united with fresh resolve and a new hope in their hearts.” And so the Acadian delegates, who had gathered for the Quebec City event, then decided to organise a similar convention in Acadia the following year, so as to “address the general interests of the Acadian people” (NOTE 4).

But the historian Léon Thériault mentions that Acadian social and political discourse had already started to take shape before the Quebec City convention. According to him, this movement of collective awareness dates back to the 1864 founding of the Collège Saint-Joseph in Memramcook and to the 1867 creation of the first Acadian newspaper, Le Moniteur Acadien (NOTE 5).

In fact, the earliest surge of Acadian national introspection was initially inspired by Rameau’s historical work, La France aux colonies (1859), and the American poet Henry Wadsworth Longfellow’s poem Évangéline (1847). In his work, Rameau maintains that an Acadian renaissance is possible. He even drew up plans that would later be used organise the first conventions: “We must create new parishes across the land, offer the people more education [...], launch a newspaper [...], establish an organisation similar to the Saint-Jean-Baptiste Society in Canada [...], choose a patron saint and a national holiday” (NOTE 6). The impact of Longfellow’s poem on Acadians is clearly evident in the speeches given by the various speakers during the conventions, particularly as they made ample references to it. In fact, every one of the early Acadian nationalists seemed to consider it to be of great national value. There is no doubt that Longfellow’s Évangéline was an important source of inspiration for them.

The First National Convention in Memramcook and the Matter of a National Holiday

In the eyes of the speakers at the first convention what they mainly saw in the Acadian people was the dispossessed, marginalised, inferior status of a people scattered across a vast territory, as well as their lack of unity and cohesion. Most of all, it was evident to them how far behind they were in matters such as education and political and economic representation, when compared to the societies that surrounded them. In 1881, the Acadian elite had gathered delegates at Memramcook from everywhere across Acadia and the Maritimes, in order to come up with solutions for these pressing issues. They believed that if no tangible measures were taken in the near future, Acadians—as a distinct people—would disappear forever.

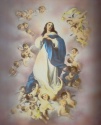

On July 20 and 21, 1881, at Collège Saint-Joseph in Memramcook, the choice of a national patron saint was the first and main issue to be debated. The debate quickly polarized into a hotly argued two-sided controversy on the very nature of Acadian nationalism and the direction it should take.

On one side were the supporters of the Saint-Jean-Baptiste (whose holiday is on June 24th)—which is the French Canadians’ national holiday. Its proponents desired to strengthen the racial, linguistic and religious ties that Acadians shared with French Canadians, so as to united with them in the defence and advancement of common interests. On the other side were the supporters of Our Lady of the Assumption (whose holiday is on August 15th). Her supporters wanted more than anything to assert and maintain the Acadian people’s uniqueness as it distinguishes them from the other peoples of Canada. As the discussions proceeded, the debate gradually heated up. One by one, each speaker held the floor, at times directing passionate, enflamed tirades at their opponents, which held a touch of bitterness.

One of the most inflamed speeches on the choice of a national holiday was given by Rev. S. J. Doucet’s, a supporter of Our Lady of the Assumption. According to Father Doucet, it was of the utmost importance that the choice Acadian people reflect their truly unique national identity, as there was no denying that the Acadian people were a distinct people. It would be their very own national holiday that would ensure the continuity of the Acadian people. The Acadian people’s fear of being assimilated by the French Canadians—which was exactly how some of the speakers saw this situation—was best portrayed by Bishop Marcel-François Richard. He asked that the Acadian people “defend their rights as a distinct people, with their own history and destiny to fulfill” (NOTE 7). He believed that they had to choose a truly Acadian holiday because choosing the Saint-Jean-Baptiste would be nothing less than sounding the death knell for the Acadian community.

The most passionate and eloquent pro Saint-Jean-Baptiste speeches—which most clearly manifested the animosity that existed between the two sides, despite being hidden behind a veil of courtesy and eloquence—were made by the eminent historian nationalist Philias Bourgeois. Bourgeois considered the choice of a national holiday in a very pragmatic light. He first presented the Acadians’ lack of social unity and political clout and the fact that they had only limited resources at their disposal to advance their cause—a situation which he boldly depicted with a certain irony directed at those who tended to envision the state of the Acadian people a little bit too optimistically in a rather excessively triumphant and glorious light. He states: “We might be able to assert our existence before other nations, but today we can hardly demonstrate our strength, our power to organise ourselves or our independence” (NOTE 8). Bourgeois deemed it necessary that Acadians strengthen the ties they shared with the French Canadians and that they obtain support when it came to their own national cause.

He then went back to emphasise a few arguments in favour of Saint-Jean-Baptiste. He thought that choosing an Acadian national holiday which was different from that of the French Canadians would be a blind and presumptuous decision: “... if we want to strand ourselves, there is no reason to do so with haste [...] Because, if we examine and assess the true worth of our numerical and political influence, our literature, our means of establishing businesses and industries [...] we must admit that we are still in our infancy [...] How would denying our situation serve us? What good would come out of such presumptuous decisions?” Finally, Bourgeois reminded his audience that the forty Acadian delegates that had been to the Quebec City convention the previous year had “established a solemn alliance between Acadia and French Canada” and had given their assent to the choice of Saint-Jean-Baptiste Day as the common national holiday for the both peoples (NOTE 9).

Our Lady of the Assumption, Patron Saint of Acadia

Pascal Poirier then took the stand to express his astonishment with the turn the debate had taken and his disappointment towards the bitterness it had generated. Despite considerable opposition, everyone agreed that once a majority consensus was reached, all would have to stand by the outcome. And so, before proceeding with the vote, the chairman of the convention, Pierre Armand Landry, expressed the point of view of all the delegates present amidst much applause: “Whatever the outcome of the vote may be [...] the decision must be accepted in good faith by the losing minority. To sum up, the holiday that will be chosen must be recognised by all of the Acadian people and celebrated as a public holiday” (NOTE 10).

When the chairman announced the Assumption to be the official choice of the majority, a round of applause broke out and all agreed to his request to ratify it unanimously. Ferdinand Robidoux gave a detailed description of the tangible joy witnessed among the delegates: “... we are witnessing a level of nationalist enthusiasm such as we have never seen before. There is no end to the cheering and hurrahs; everyone is caught up in the fervour of strong emotion” (NOTE 11). On September 16, 1881, after the bishops of the Roman Catholic Ecclesiastical Province of Halifax had received the petition sent by Bishop M. F. Richard, the Maritimes’ Episcopate gave their approval for the Assumption as the Acadians’ national holiday, which was to be celebrated each year on August 15th.

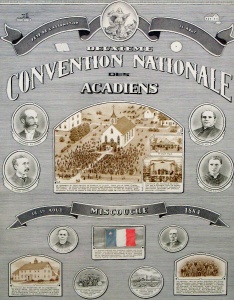

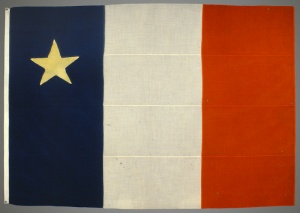

The Second National Convention in Miscouche and the Matter of an Acadian National Flag

Acadians still needed to adopt a set of strong national symbols representative of their cultural unity. During the second Acadian convention, which was held in Miscouche, Prince Edward Island on the 15th of August of 1884, Bishop M. F. Richard gave a fervent discourse in favour of the adoption of a distinctly Acadian national flag. In his speech, he continued on with the same autonomist discourse that he had used during the first convention, but this time it was stated unequivocally in military terms: “At the great 1881 convention held in Memramcook, we joined together in an orderly army set for battle, not to wage war on our brothers who share our religion, but to defend ourselves against any threat made to our nationhood” (NOTE 12). He even went further with the military metaphor saying that this army needed a banner, “a national flag”. He then proposed the French flag, the former homeland of all Acadians, to which of a truly Acadian symbol would be added: “I wish that the Acadian people could have a flag that reminds them not only that they are the offspring of France, but also one that reminds them of their Acadian-ness [...] through the addition of a star in papal colours to the blue stripe. The star represents Our Lady Mary’s star, the Stella Maris” (NOTE 13). According to the fervently passionate priest, once the flag became a national symbol, it could serve as an emblem around which Acadians would gather to continue their struggle to obtain and maintain their rights. Those present at the convention enthusiastically and unanimously ratified this choice of a flag as the national emblem of Acadia, and then concluded with the singing of the French national anthem, La Marseillaise.

The Unveiling of the First Acadian Flag and the Choice of an Acadian National Anthem

As the convention was nearing its end, Bishop Richard announced that he would put the Acadian flag he had had prepared beforehand on display, so confident was he that the assembly would endorse his proposal. In the spate of Acadian nationalism that was reaching its climax, the choice of the national anthem was spontaneous and generated a fresh surge of patriotism. Here is how eye-witness, Ferdinand Robidoux, describes the scene:

“In a solemn silence before the gaze of a much moved audience, Bishop Richard and Father Cormier unfolded a beautiful tricolour adorned with a single star in papal colours. Everyone shared in their enthusiasm and people cheered as the national standard was unveiled for the first time. The whole room requested a song to commemorate the occasion, some suggesting La Marseillaise, when Mr. Richard started to sing Ave Maris Stella in a deep solemn voice, which was then taken up by the whole audience. It was a wonderful and moving sight to behold [...] and then, Mr. Richard, addressed the crowd, expressing his desire that some of our very own musicians would soon be able to provide Acadia with a national anthem. He was then interrupted by Mr. Pascal Poirier, who requested to speak for a brief moment. More than all present, he was particularly moved by the proceedings and with a catch in his voice he announced that he believed that the anthem had already been found and in a most wonderful way that clearly showed not only the hand of God in the matter, but also that of Mary, our patron saint. [...] It is this very hymn lead by Bishop Richard and sung by the whole audience…it is the Ave Maris Stella” (NOTE 14).

And so it was that Pascal Poirier, as well as Bishop Richard who had a hand in the choice of the national anthem, although people generally only give credit to Bishop Richard. Chairman Landry then proposed a motion that the hymn be adopted as the Acadian national anthem and moved that the assembly approve it. The motion was accepted amidst much enthusiastic cheering. For everyone present, this was obviously an event of historic importance, one embodying the awakening of the Acadian people and in some way the restoration of the historic continuity which had been shattered by the 1713 conquest and the Deportation of 1755. An account published in the Moniteur Acadien reads: “The scene of the adoption of the national flag and the national anthem, Ave Maris Stella, was a solemn one and moved many to tears. Instead of sounding the death knell for the Acadian people as they had feared, they were enthusiastically saluting their flag, the symbol the of a people’s national vitality, as they stood on their own two feet for the first time since 1713” (NOTE 15). The Acadian flag was hoisted for the first time the following day, on Saturday August 16th, in front of the St, John the Baptist Church in Miscouche. It still flies there to this day, after more than 125 years.

The Lasting Impact of the First Two Acadian National Conventions

The 1881 and 1884 conventions are among some of the most memorable of all the great gatherings of the Acadian people. For the first time, Acadians openly asserted themselves as a people distinct from the French Canadians, with their own history, hopes, traditions and customs, who had a unique destiny to fulfill. Significant national symbols were chosen there with the purpose of rallying the Acadians together as a people and uniting them for the struggle that would eventually lead them to secure for themselves their long-awaited fundamental rights. Acadians endowed themselves with a patron saint, a national holiday, a flag, an anthem, a motto (L’union fait la force “Unity is Strength”) and a national insignia.

Moreover, the Memramcook and Miscouche conventions launched an ongoing tradition of great gatherings of the Acadian people—today known as the Global Acadian Conventions—which have been held every four years since 1994. Yet, the most significant legacy of these conventions is without a doubt the flag which flies proudly today over every city and town of the Maritimes where Acadians have established themselves, and one must not forget the Acadian national holiday on August 15 (Our Lady of Assumption Day), which is celebrated with enthusiasm every year all over Acadia.

Denis Bourque, Ph. D.

Full professor

Faculty of French Studies

Université de Moncton

1. Only the sermons and speeches of the first three national conventions were compiled in a volume and published in 1907 by Ferdinand Robidoux. We intend to publish them in the near future in an edition which includes critiques, along with the sermons and speeches of the other national conventions that were held between 1907 and 1937, but whose records remain scattered among various newspaper articles to this day. The first national convention of French Canadians organised by the Société Saint-Jean-Baptiste was held in Montreal on June 24, 1874. A young Pascal Poirier, postmaster for the House of Commons, and Pierre-Amand Landry, then provincial Member of Parliament, were in attendance as Acadian representatives. Poirier would later become the first Acadian to be appointed to the senate. Landry became the first Acadian to be appointed Minister in the Legislative Assembly of New-Brunswick, then as a judge and later Chief Justice of the Supreme Court of the province. He was one of the key organisers of the first Acadian National Conventions.

3. S'émoyer: “To inquire earnestly about”. Throughout his life, Pascal Poirier had a passion for the Acadian dialect. Through the writing an essay entitled Le Parler Franco-Acadien et Ses Origines [French Acadian Speech at its Origins], as well as a glossary (first published in a fascicle format and recently published by Pierre Gérin under the title Glossaire Acadien) Poirier wished to restore the dialect to the level of respect he thought it deserved. Pascal Poirier never shied away from using this language that some others considered to be a patois. Pascal Poirier, Le Glossaire Acadien, Édition critique établie par Pierre M. Gérin, Moncton, Centre d'études acadiennes et Éditions d'Acadie, 1993, p. 155.

5. Léon Thériault, “La première Convention nationale des Acadiens, Saint-Joseph-de-Memramcook, les 20 et 21 juillet 1881”,Les Cahiers de la Société historique acadienne, vol. 12, No 1, 1981, p. 5.

6. Edmé Rameau de Saint-Père, La France aux colonies. Études sur le développement de la race française hors de l'Europe. Les Français en Amérique. Acadiens et Canadiens, Paris. A. Jouby, 1859. See Marguerite Maillet, Histoire de la littérature acadienne, p. 55.

8. Ferdinand Robidoux, Convention Nationales des Acadiens ..., p. 52-53. The historical triumphant attitude, often intrinsically linked to the idea of a manifest destiny for the Acadian people, became one of the major rhetoric themes of the speeches given at the national conventions. In literature, Napoléon Landry (on whom the Academie Française conferred the Grand Prix de la Langue Française [French language award] for his collection Poèmes Acadiens published by Fides) was probably the author who expressed this concept the most eloquently.

15. Le Moniteur acadien, August 21, 1884, quoted by Robidoux, p. 156. “”

Degrâce, Eloi. “L'Ave Maris Stella”, La Revue d'histoire de la société historique Nicolas-Denys, vol. 6, no 1, 1978, pp. 41-48.

Degrâce, Eloi. “L'hymne national acadien”, Les Cahiers de la Société historique acadienne, vol. 16, no 1, 1985, pp. 11-18.

Emont, Bernard. “Les Conventions nationales : 1881, 1884, 1890”, Les Amitiés acadiennes, no 24, 1983, pp. 14-15 ; no 25, 1983, pp. 16-17.

Emont, Bernard. “Les Conventions nationales : 1881, 1884, 1890”, Les Amitiés acadiennes, no 24, 1983, pp. 14-15 ; no 25, 1983, pp. 16-17.

Léger, Maurice A., “Centenaire du drapeau acadien - Un historique”, Les Cahiers de la Société historique acadienne, vol. 14, no 4, 1983, pp. 107-152.

Mailhot, Raymond, La “Renaissance acadienne” (1864-1888), l'interprétation traditionnelle et Le Moniteur Acadien, M.A. Thesis, Université de Montréal, 1969, 486 p.

Perron, Judith, “Le Discours social des premières conventions nationales acadiennes”, Revue Frontenac Review, no 9, 1992, pp. 30-44.

Richard, Camille-Antoine, “Le discours idéologique des conventions nationales et les origines du nationalisme acadien. Réflexions sur la question nationale”, Les cahiers de la Société historique acadienne, vol. 17, no 3, 1986, pp. 73-87.

Richard, Camille-Antoine, L'idéologie de la première convention acadienne, M.A. Thesis, Laval University, Quebec City, 1960, 124 p.

Robidoux, Ferdinand, Conventions nationales des Acadiens. Recueil des travaux et délibérations des six premières conventions, compiled by ..., vol. I, Memramcook, Miscouche, Pointe de l'Église, 1881, 1884, 1890, Shédiac, Imprimerie du Moniteur Acadien, 1907, xxix, 281 p. The second volume dedicated to the following three conventions was not published.

Thériault, Léon, “La première Convention nationale des Acadiens, Saint-Joseph-de-Memramcook, les 20 et 21 juillet 1881”, Les Cahiers de la Société historique acadienne, vol. 12, no 1, 1981, pp. 5-35.

Additional DocumentsSome documents require an additional plugin to be consulted

Images

-

-

Affiche de la deuxièm

Affiche de la deuxièm

e convention na... -

Collège Saint-Joseph

Collège Saint-Joseph

de Memramcook, ... -

Délégués acadiens à l

Délégués acadiens à l

a deuxième conv...

-

Dessin de la seconde

Dessin de la seconde

église de Misco... -

Écoliers posant fière

Écoliers posant fière

ment devant un ... -

Église de Miscouche (

Église de Miscouche (

île-du-Prince-É... -

Festival acadien, 200

Festival acadien, 200

7

-

Festival acadien, 200

Festival acadien, 200

7 -

Insigne de la Société

Insigne de la Société

nationale de l... -

L'Acadie NOUVELLE: Ma

L'Acadie NOUVELLE: Ma

rio Landry. 15 ... -

L'Acadie NOUVELLE: Ma

L'Acadie NOUVELLE: Ma

rio Landry. 15 ...

-

L'Acadie NOUVELLE: Ma

L'Acadie NOUVELLE: Ma

rio Landry. 15 ... -

L'Acadie NOUVELLE: Ma

L'Acadie NOUVELLE: Ma

rio Landry. 15 ... -

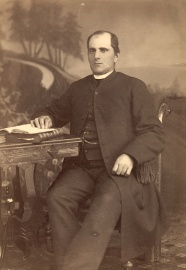

Le père Camille Lefeb

Le père Camille Lefeb

vre, fondateur ... -

Le premier drapeau ac

Le premier drapeau ac

adien dévoilé à...

-

Le prêtre et historie

Le prêtre et historie

n Philias F. Bo... -

Le tintamarre de Cara

Le tintamarre de Cara

quet -

Le tintamarre de Cara

Le tintamarre de Cara

quet -

Monseigneur Marcel-Fr

Monseigneur Marcel-Fr

ançois Richard ...

-

Monument funéraire de

Monument funéraire de

Pierre-Amand L... -

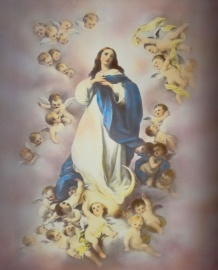

Notre-Dame de l’Assom

Notre-Dame de l’Assom

ption -

Page couverture du li

Page couverture du li

vre de Jean-Mar... -

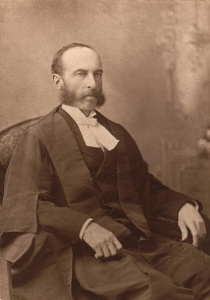

Pascal Poirier

Pascal Poirier

-

Pierre-Amand Landry

Pierre-Amand Landry

-

Plaque descriptive de

Plaque descriptive de

l'église Saint... -

Tintamarre à Pointe-d

Tintamarre à Pointe-d

e-l'Église, Nou... -

Tintamarre au Festiva

Tintamarre au Festiva

l acadien de Sa...