Victoria Cross: French-Canadian Recipients

par Pépin, Carl

The Victoria Cross is a military decoration awarded for “most conspicuous bravery, or some daring or pre-eminent act of valour or self-sacrifice, or extreme devotion to duty in the presence of the enemy.” This British decoration was created during the reign of Queen Victoria. It constitutes the highest recognition attributed to soldiers or civilians serving in the armed forces of the British Empire and, subsequently, the Commonwealth. Three French-Canadian soldiers have received the Victoria Cross: Corporal Joseph Kaeble, Lieutenant Jean Brillant, and Captain Paul Triquet.

Article disponible en français : Croix de Victoria : récipiendaires canadiens-français

Victoria Cross

The Victoria Cross is the highest award attributed for bravery “in the presence of the enemy” to soldiers and civilians in the armed forces of the British Empire and Commonwealth. This medal takes precedence over all the other civilian and military medals, decorations, and orders in the British honours system. The Victoria Cross may be awarded to persons of all ranks. As instructed by Queen Victoria at the moment of its creation on January 29, 1856, it was to be attributed regardless of the recipient’s rank, ethnicity, creed, or social status.

The Victoria Cross has its own specific physical characteristics; what is more, no two medals are exactly the same. It takes the form of a cross pattée, has a dark brown finish, and, in principle, is made from cannons captured from the Russians during the Crimean War (1853-1856). It measures 41 mm high by 35 mm across (15/8 x 13/8 in.). The obverse shows a lion guardant over St. Edward’s Crown, with FOR VALOUR inscribed below. On the reverse, the date of the recipient’s act is engraved inside a raised circle.

The mounting, which is ornamented with laurel leaves on the obverse, comprises a straight bar with a slot at the top for the ribbon and with a centred V-lug below. A small link passes through the V-lug, attaching it to a semi-circular lug on the top arm of the cross. The reverse of the suspension bar is engraved with the recipient’s name, rank, and regiment name (or number). The crimson ribbon is 38 mm (1½ in.) wide. The cross itself weighs 27 grams (0.95 oz.).

The history, prestige, and awarding of a decoration

The process for awarding the Victoria Cross is quite strict. Eligibility is established through general criteria, the medal being awarded on grounds of “most conspicuous bravery, or some daring or pre-eminent act of valour or self-sacrifice, or extreme devotion to duty in the presence of the enemy,”(NOTE 1) as defined by Royal Warrant in 1856.

Once this is established, a Victoria Cross candidate, whether alive or dead, must be recommended by an officer from the regimental or equivalent level and must be supported by three direct witnesses to the event. The candidate’s file is then passed up the military hierarchy until it reaches the Secretary of State for Defence (the Minister). Once there, formalities are completed and the monarch approves the award by signing an official document. Victoria Cross awards are then published in the London Gazette with an official citation describing the act of bravery.

As the United Kingdom’s highest distinction, the Victoria Cross takes precedence over all other military decorations and titles. Because of its status, the Victoria Cross is always the first decoration worn in a row of medals. The recipient is authorized to affix the initials “V.C.” to his signature in all circumstances; these same initials take precedence over all other titles that he is authorized to write. A Canadian Victoria Cross was created in 1993 to replace the British decoration, the awarding of which was discontinued in the early 1970s. The new decoration was presented to the public for the first time in a ceremony in Ottawa in 2008. At the time of writing, only 1,356 Victoria Crosses had been awarded to 1,353 soldiers (NOTE 2). Of this number, three were French-Canadian soldiers.

Feats of arms

Québec’s cultural and historical interest for the Victoria Cross has informed our reading and commemoration of the feats of arms of the three French-Canadian recipients, namely Corporal Joseph Kaeble, Lieutenant Jean Brillant, and Captain Paul Triquet. The first two were members of the 22nd Battalion (French-Canadian) (NOTE 3) and received their decoration posthumously in 1918. As for Captain Triquet, he became a member of the Royal 22e Régiment in 1943. Their acts stand as shining examples of valour and heroism in tragic situations.

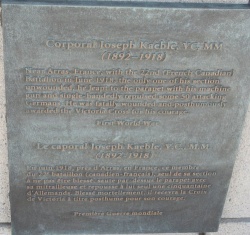

On the night of June 8, 1918, in the region of Amiens in France, Corporal Joseph Kaeble, a veteran of the 22e Régiment, was posted in a front-line trench where he commanded a machine gun section. Suddenly, the enemy artillery began to bombard the trench held by Kaeble and his men, and kept on firing for close to an hour. When it ended, Kaeble realized that he was the only uninjured soldier in his section. Stunned and disoriented, he looked out into no man’s land only to see tens of German soldiers charging his position.

Corporal Kaeble jumped over the parapet and, with his machine gun on his hip, preceded to fire some 20 magazines with 47 cartridges each at the enemy. Though hit several times by shrapnel, he kept on firing until he finally fell backward into the trench. Lying on his back, gravely injured, his legs broken, he fired his last cartridges over the parapet. The Germans retreated. Before losing consciousness, he shouted to the injured around him, “Hold on boys! Don’t let them through! We have to stop them!” Corporal Kaeble died from his wounds in hospital the next evening. He was the first French Canadian soldier to be decorated with the Victoria Cross.

The event described below underscores just how horrible the combats fought by the 22nd Battalion in 1918 were. On August 8, the battalion participated in the taking of the town of Amiens. During the offensive, the battalion was ordered to clean up some of the surrounding villages with the help of seven tanks. Arranged in order of battle, the battalion’s officers and soldiers began their attack, with Lieutenant Jean Brillant among the officers leading the charge.

Brillant noted, early in the advance, that an enemy machine gun was considerably slowing their progression by holding his company’s left flank in check. He rushed all alone towards it and killed the two gunners. Though injured in the left arm, he refused to be evacuated and returned to combat the next day. Leading two platoons into a bayonet and grenade combat, he captured another 15 machine guns and took 150 prisoners.

On August 9, he incurred a head injury but refused once again to be evacuated. During the day, he led the charge against a canon firing directly on his unit. Hit by shrapnel in the stomach, he slowly continued his advance toward the unit’s target until finally he crumpled, exhausted and unable to rise. He held on to life in a field hospital for a few hours, only to die the next day. Lieutenant Brillant received the Victoria Cross posthumously for exceptional bravery in the completion of duty. During this battle, the 22nd Battalion lost 7 officers and 262 men.

A third French-Canadian soldier was awarded the Victoria Cross due to events that occurred in the Second World War on the Italian Front, in December of 1943. Before Rome could be captured, a series of objectives had to be secured, one of them being the roads around Ortona, on the Adriatic Coast. The Royal 22e Régiment was assigned to capture the crossroads linking Ortona to the hamlet of Casa Berardi. The sector was being held by elite German troops comprised of parachute and armoured divisions. On December 14, 1943, C. Company was ready to attack. It was commanded by Captain Paul Triquet, a career soldier who began the war as Regimental Sergeant-Major. With the support of an Ontario Tank Regiment squadron, C. Company began its attack on Casa Berardi’s fortified point.

The difficulties became apparent right from the beginning. The small ravine in front of them was strongly defended and Triquet’s detachment ran into heavy machine gun and mortar fire. All of the company officers and half of its men were killed or wounded at the outset. What is more, the enemy manoeuvres had separated C. Company from the rest of the regiment. Seeing that the situation had become critical, Captain Triquet rallied his men with these words: “We are surrounded. The enemy is in front, behind, and on our flanks. The safest thing to do is move forward and take our objective.”

The company was now 1,600 metres (1 mile) from Casa Berardi. Only thirty men remained, including one officer and two sergeants to command them. Surrounded before reaching their target, Triquet ordered that they charge it once again. They rushed forward and broke through the enemy line. Four German tanks were destroyed and several enemy machine gun posts were silenced during this engagement. In preparation for a counterattack, Captain Triquet immediately organized a defensive perimeter around the remaining Canadian tanks with a handful of men, declaring, “They shall not pass!”

A German counterattack supported by tanks came almost immediately. Captain Triquet was everywhere, firing on the enemy, encouraging his men, and directing the defence. They used all the weapons available to them. This and subsequent German attacks were pushed back with heavy losses. Cut off from the rest of the Allied troops, Captain Triquet and his small group stood firm against larger forces. The Royal 22e Régiment finally succeeded in breaking the German encirclement of C. Company, capturing Casa Berardi.

By the time it was relieved the next day, Company C. had only fifteen men left and a handful of armoured vehicles. Captain Triquet’s inspirational command had led to the taking of Casa Berardi. Once it fell, the road was clear to launch an attack on the vital Ortona junction and, ultimately, on Rome. Captain Triquet was awarded the Victoria Cross for his heroism. He later learned that his company had suffered 23 dead and 107 wounded.

Recognition of heroism: French-Canadian recipients

There are several tangible traces that bear witness to a desire to commemorate these heroes’ feats. There are, for example, Kaeble and Joseph-Kaeble Streets in Québec City, Rimouski, and Sayabec, as well as a Mount Kaeble near the Base des forces canadiennes Valcartier and a Lake Kaeble in the Laurentian wildlife reserve. In Montréal, Jean-Brillant Street is a sizeable artery in the heart of Université de Montréal’s campus. Several public buildings have likewise been named after these men. The Maison Paul-Triquet, which opened its doors in 1987 in Québec City, is a home-care centre that is affiliated with the Centre hospitalier universitaire de Québec. It is financed by Veterans Affairs Canada and takes in veterans in need of long-term care. Various other monuments, statues, plaques, and inscriptions likewise keep their memory alive.

The Valiants Memorial in Ottawa, which commemorates the outstanding actions of 14 soldiers in Canada’s history, comprises busts of Corporal Joseph Kaeble and Major Paul Triquet. The Victoria Cross is engraved on the gravestones of Jean Brillant and Joseph Kaeble, respectively buried in the cemeteries of Wancquetin and Villiers-Bretonneux in France. The Victoria Crosses of its recipient members are carefully conserved in the Museum of the Royal 22e Régiment at the Citadelle in Québec City, where an exhibit tells their story. The ashes of Major Paul Triquet likewise rest at the Citadelle in the Mémorial du Royal 22e Régiment. The Officers’ Mess and the Warrant Officers’ and Sergeants’ Mess each have their Victoria Cross Gallery where portraits and paintings of the recipients are exhibited.

Another element that contributes to keeping the memory of the Victoria Cross alive involves “regimental indoctrination” courses that are given each year by the Royal 22e Régiment’s official historian. An account and analysis of the recipient’s feats of arms are given to the regiment’s officer cadets, with the goal of enhancing esprit de corps. Canada’s Department of Veterans Affairs likewise publishes and updates a variety of documents and instructional tools recounting its soldiers’ feats.

Carl Pépin

Ph. D., Historian

NOTES

1. « (...) most conspicuous bravery, or some daring or pre-eminent act of valour or self-sacrifice, or extreme devotion to duty in the presence of the enemy (...) »

2. Trois soldats ont obtenu la Croix de Victoria à deux reprises.

3. Cette unité dissoute en 1919 devint dans les années 1920 le Royal 22e Régiment.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

BERNIER, Serge, Le Royal 22e Régiment 1914-1999, Montréal, Art Global, 1999, 455 p.

BRAZIER, Kevin. The Complete Victoria Cross, Royaume-Uni, Pen and Sword, 2010. 406p.

CHABALLE, Joseph (Colonel), Histoire du 22e Bataillon (Canadien français), 1914-1919, Tome I, Montréal, Éditions Chanteclerc Ltée, 1952, 415 p.

MACFARLANE, John. Triquet's Cross - A Study in Military Heroism, Montréal, McGill-Queen's University Press, 2009. 250p.

MULHOLLAND, John et Alan Jordan. The Victoria Cross Bibliography, Royaume-Uni, Spink & Son Ltd., 1999. 236p.

REYNOLDS, Ken, Pro Valore. La Croix de Victoria canadienne, Ottawa, Ministère de la Défense nationale, s. d. 60p.

Additional DocumentsSome documents require an additional plugin to be consulted

Images

-

Buste de Joseph Keabl

Buste de Joseph Keabl

e au Monument a... -

Buste de Paul Triquet

Buste de Paul Triquet

au Monument au... -

Caporal Joseph Kaeble

Caporal Joseph Kaeble

, VC, MM -

L'avers et l'envers d

e la croix de V...

-

La croix de Victoria

La croix de Victoria

telle qu'elle a... -

La rue Joseph-Keable

La rue Joseph-Keable

dans le quartie... -

La rue Triquet dans l

La rue Triquet dans l

e quartier Sain... -

Le lieutenant Jean Br

Le lieutenant Jean Br

illant qui a re...

-

Le Major Paul Triquet

Le Major Paul Triquet

quitte le Buck... -

Le Monument aux Valeu

Le Monument aux Valeu

reux, Ottawa -

Lieutenant Jean Brill

Lieutenant Jean Brill

ant, VC, MC -

Notice sur le Caporal

Notice sur le Caporal

Joseph Keable,...