Christmas Celebrations

par Warren, Jean-Philippe

Christmas has not always been the centre of interest with French-Canadians through the months of December and January. Up until the late 19th century, New Years Eve was the community's most important winter time celebration. It is quite surprising that, under the joint influence of Catholic priests and shopkeepers, French Canadians gradually began to celebrate and cherish Christmas more than New Year's Eve. But, where the clergy had wanted to impose the image of baby Jesus, it would finally be Santa Clause who would quickly become the ideal holiday symbol.

Article disponible en français : Célébrations de Noël

An Ever-evolvingTradition

Up until the end of 19th century, New Years Eve was the winter's most popular holiday for French-Canadians. As late as 1905, some Montreal shops were still retailing their holiday wares as if jolly old Saint Nicholas would visit Montreal twice, first stopping to grace the homes of the English Canadians and then later to bring holiday cheer to their French speaking compatriots. "I have been very busy since I arrived, said a fictional Santa Clause. [...] Luckily, half of my work is done, having visited the whole western end of the city, from Saint-Laurent Street to the western edge of Westmount. I've set next week aside for my dear little Canadians (NOTE 1) who, I hope, will be happy with me on the morning of New Years Eve (NOTE 2)."

New Years Eve complements Christmas, while being different from it in many ways: the holiday is rather of a pagan nature, it is centred on neighbourhood instead of family, it is a time for bouts of drinking and does not take place at home. But then, the Victorian etiquette of the time, favouring self-restraint and privacy, as well as the Ultramontane dogma [the supremacy of papal creed over all matters in the lives of Roman Catholics] and commercialism would, little by little, help to impose December 25th as the main holiday, gradually shifting the focus of the holiday towards children. And so the holiday enabled the Roman Catholic Church to have every one honour the birth of Christ, shopkeepers were pleased to make French Canadians children their target clientele and parents could develop habits that would foster increasingly more tight-knit families.

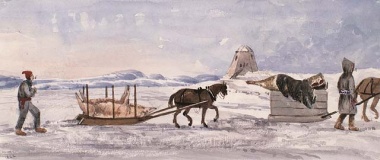

Of course, since the "heroic" early days of New France, Christmas had been celebrated in the French-Canadian country side. Early 19thcentury, Advent started during the final days of November. It was a time of spiritual preparation during which people awaited the coming of the Christ. These four weeks also called Little Lent were a time of penitence, which ended with the Roman liturgical celebration of Jesus' baptism on January 13th (although many parishes keep their nativity scene up until the celebration of the presentation of Jesus in the temple and of the purification of the Virgin Mary on February 2nd). The Roman Catholic Christmas revolves around the Midnight Mass and Christmas Eve. French-Canadians did not exchange gifts and neither did they send Christmas cards, eat turkey or plum pudding. For them Christmas was a solemn occasion, a time for reflection and prayer, but also season of family gatherings, a time during which they celebrated the birth of Christ.

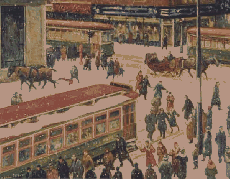

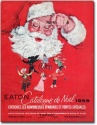

Growing Commercialisation

Catholic as it may be, Christmas would become a commercial event duringthe late 19th century. On the one hand, a visit to church for the Midnight Mass was still mandatory, but on the other hand, more and more, the Christmas tree, with its decorations, mistletoe, is what had come to symbolise Christmas Eve (even though it still sheltered a nativity scene and was topped with a cross or an angel). More importantly, for many the tree had begun to evoke the "traditional season of Christmas shopping" as it began to be called, as early as the 1900s. Starting on the fourth Thursday of November, people in Montreal, Quebec City and elsewhere across the province would hurry to department stores and spend hours trying to find a New Year's Eve present for their spouses, children, nephews, aunts, friends or colleagues. Father Christmas, who, by 1880, was already visiting Montreal in his current incarnation, years before Coca-Cola's publicity campaigns, came to embody the joyous spirits of the holiday festivities in which excesses (food or spending) had become the predominant theme (NOTE 3).While the Catholic Church tried to impose the image of a baby Jesus, with Père Fouettard as assistant, consumerist society was able to offer a divinity of avery different ilk: he was jolly, goodhearted, liberal and lenient.

Christmas parades were organised in the streets of Montreal and Quebec City at the beginning of the 20th century. The events attracted so many people that riots sometimes broke out and the police had to be called into manage the crowds. And so, in 1906, the owner of the Quebec City department store Magasin Paquet, located on Saint-Joseph Street, organised a Christmas parade. Leaving his "Kingdom in the North Pole", he arrived in the provincial capital city on the Trois-Rivières train and made a triumphal visit through the main streets of the city travelling in a carriage pulled by three horses. Escorted by a detachment of police officers, marching to the sound of a brass band, the procession lasted two and a half hours. Thousands of children came out to greet their "old friend", to shout frantic "hoorays" and to blow fanfares on their tin trumpets as he passed by. Santa Clause would wave to them, blow them kisses and hand out colouring books, toys and candies to each of them. The crowd would give him a standing ovation before he would return to his headquarters in the basement of the store (NOTE 4).

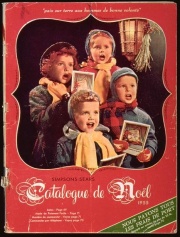

It is not surprising that the central virtue of the holiday became generosity. Shopkeepers would try to convince people to go spend in the city's downtown stores or in the villages'general stores or to use mail order catalogues (Eaton's and Paquet's, the veritable forbearers of the Internet!). In other words, a few weeks of excess expenditure and excessive luxury were indulged. Clients were strongly encouraged to give to others what they wouldn't dream of buying for themselves, and although newspaper ads sometimes suggested mixing good business sense with pleasure, in the end pleasure almost always won. Children were at the very heart of the holiday spirit for the simple reason that they were considered to be beings of multiple desires (and not of needs), frivolous beings with a Christmas gift list that would never end.

Everyone, priests and shop owners alike, came together to encourage Quebeckers to give freely. But, after a time, the appeal to Christian generosity was quickly absorbed by the shopping rhetoric. The truly pious French-Canadians were those who would buy for people really in need of gifts that they would not be able to afford otherwise. Various charities such as "Meals for the Sick", "Gifts for the Poor" and the "Bazaar for the Poor" were some of the organisations (now replaced in part by the media's Big Food Drive) that were first to incarnate the new values of that era. Their wish for every French-Canadian was that they be touched by the enlightement of true brotherhood, a feeling to be achieved by offering gifts. It was believed that the way to happiness was, for the rich, to act as Santa and offer gifts, selflessly thinking about others before themselves. The ideal was to follow his example and go to the poor with arms full of gifts.

An Ambigious Cultural Heritage

Christmas is an ambiguous cultural heritage. Celebrated around the world and internalised by every culture, Christmas is considered a national holiday which is supposed to belong to each culture. Rooted in what is supposed to be immemorial if not mystical traditions, it welcomes all that is new and encourages all trends. Greeted as a moment of reflection and human warmth, it celebrates trinkets and gadgets. It paradoxically takes place both on a universal and local level, a traditional and contemporary level, as well as on a personal and commercial level. For that reason, it could be considered to be the first "postmodern" ritual of the French-Canadian society: it merges what are normally opposing trends and creates a combination of opposites that lends the winter season its strength and its magic. Today, with our familiarity with the imaginary world of Walt Disney, it is easier to understand that sometimes, cultural heritage can be at the same time artificial and authentic, ancestral and new, magical and centred on a consumerist society. Far from excluding one another these opposites feed on each other carried on by a myth powerful enough to give a human face to mass production, to infuse magic into manufactured goods and to give the impression that businesses are selling without seeking any profit (NOTE 5).

But, it is also important to point that, although the commercial Christmas seems to deny the religious Christmas, the postmodern Christmas is inherently profane and sacred. Santa Clause is a sort of divinity that performs miracles, flying down from the skies and magically making gifts appear out of nowhere; Christmas carols are hymns; people constantly speak of the Christmas magic, etc. Thus, on the morning of December 25th, the consumerist society fulfils the dream it otherwise betrays every other day: it takes delight in its material objects, it gives through its purchases, it unites with its individualism and makes self-sacrifices with profit in mind (after all, were not sales called "sacrifices" at the turn of the 20th century?).

Mixing and Matching the Christmas Customs of Various Cultures

At a time where Christmas has proven to be more and more commercial, people have started to wax nostalgic, one phenomenon generating the other. On the one hand the traditional tales evoke past traditions and memories of times long gone that are brought back to life via glittering fields of ice, icy roads, floodlit churches, naïve and touching carols, all which contrast so greatly with the worldly celebrations of big cities. On the other hand, the commercialised Christmas rhetoric is elevated to that of a true tradition: Santa Clause continues to ride in a sleigh in the age of the automobile. People celebrate the magic of Christmas in an era of great rationalism. There is an emphasis on the belief that gifts are free in a time where it is possible to purchase nearly everything. People seem to believe that the transformation of Christmas into a commercial holiday was in some way the direct result of the evolution of Roman Catholic, Celtic or Gaulish customs. But something that is even more significant is that people have begun to assimilate the commercial Christmas into the authentic Christian traditions, which have been threatened by the general disenchantment of society.

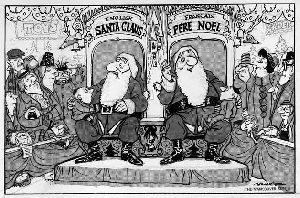

Yet the variety of borrowings from other cultures reveals what a contradictory tradition Christmas really is. In Quebec, the contemporary Christmas celebrations include an American Santa Claus, a Catholic Midnight Mass, greeting cards that first became popular in England, a German Christmas tree and Christmas wreath (of mistletoe, here replaced by holly), which is of French and Anglo-Saxon origins. Most of these elements, either pagan or profane, have been integrated to Christmas only recently, that is, little more than a century ago, yet these have afforded the whole hodge podge creation to take place in a decor that gives winter time its unique atmosphere.

If these symbolic traditions (to which can be added the Yule log, lights, canned snow and tinsel) are largely shared by all North American families, there is still a desire to make Christmas more of an indigenous celebration, thereby lending it more of a local flavour. The Christmas tales and legends, which have multiplied over the years, are intended to legitimise what turns out to be pure novelties (such as the Dutch Christmas stockings). On that topic, the story of how the name Père Noël (Father Christmas) came to be chosen is particularly interesting.

The jolly, silver-bearded, pot bellied one arrived in Quebec around 1880 under the name of Santa Claus. He was to suffer the wrath of the Roman Catholic Church (who considered him to be a Protestant concoction), as well as that of the French-Canadian nationalists (who thought him to be too English) and the Imperialist partisans (who, during World War One, deemed the Teutonic character to be unpatriotic). And so, at the beginning of the 20th century, he was renamed Père Noël [Father Christmas - a very French name indeed], but not without first flirting with various names: Saint Nicolas, Kris Kringle, Petit Noël [Little Christmas] and Bonhomme Noël [Jollyman Christmas], if only for a short time. To illustrate this naming and renaming of the mythical figure, in 1912, a French-Canadian reporter wrote the story of his nephew, of whom he had asked him to see the letter in which the child had written his gift list. The letter was addressed to "meusieu [Mister] Centa-Classe". To say the least, the godfather was furious:

"Who is the man to whom this is addressed?"

"You know, the one who gives us toys."

"My dear nephew, I thought Santa Claus was the one who went to the homes of the little Anglos in Westmount. When I was a kid,we little Canadians were more patient then you are. We would wait eight days after Xmas for Père Noël [Father Christmas], a nice old trapper sort of chap, to come. We were even told that he would travel with another very mean, old man called the Père Fouettard, who would give children that had been bad a whipping." (NOTE 6)

A Return to a "Genuine" Christmas?

For a century now, there has been an increasing amount of criticism about the ever-growing commercialisation of Christmas. Which is surprising, considering that businessmen of every ilk have been making good use of the holiday since the 19th century. The nostalgia for a genuine Christmas is a truly contemporary feeling. Today, the reality of the Christmas holidays is well established and all the different variations that have emerged over the years are centred around a common theme: the purchasing and exchanging of gifts, decorating the family home and family diners. These are all part of the social customs that all must observed if one is to be happy. Neglecting to exchange gifts or to shop on Christmas Eve alone is considered by almost everyone as either as a good way to provoke the ire of the Christmas Spirit or to be struck with a curse. And so, in the case of Quebec's Christmas tradition, which is less than truly original to say the least, one does not bring in the new with the old, but the old with the new.

Jean-Philippe Warren

Member of the Research Chair forthe Study of Quebec

Professor, Department of Sociology, Concordia University

NOTES

Note 1. At the turn of the century, English-speaking Canadians were called "les anglais [the English]" by French Canadians. The term Canadian was only used to refer to the people today known as the French Canadians ,particularly the Quebeckers. It wasn't until after World War I that all citizens of Canada started to call themselves Canadians.

Note 2. Advertisement from the store Au Bon Marché, La Presse, December 22nd 1905, p. 26.

Note 3. Jack Elliott, Inventing Christmas. How Our Holiday Came to Be, New York, Harry N. Abrams Publications, 2002.

Note 4. Jean-Philippe Warren, Hourra pour Santa Claus! La Commercialisation de la Saison des Fêtes au Québec, Montreal, Boréal, 2006.

Note 5. Leigh Eric Schmidt, Consumer Rites. The Buying and Selling of American Holidays, Princeton, Princeton University Press, 1995.

Note 6. Louis Breton, "Santa Claus", Le Devoir, December 16th 1912, p. 1.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Georges Arsenault, Noël en Acadie, Tracadie, La Grande Marée, 2005.

Sylvie Blais et Pierre Lahoud, La fête de Noël auQuébec, Montréal, Les Éditions de l'Homme, 2007.

Sophie-Laurence Lamontagne, L'hiver dans la culture québécoise (XVIIe-XIXe siècle), Québec, Institut québécois de recherche sur la culture, 1983.

Jacques Lamothe, Le folklore du temps des fêtes, Montréal, Guérin, 1982.

Raymond Montpetit, Le Temps des fêtes au Québec, Montréal, Les Éditions de l'Homme, 1978.

Martyne Perrot, Ethnologie de Noël: une fête paradoxale, Paris, Grasser, 2000.

Jean-Philippe Warren, Hourra pour Santa Claus! La commercialisation de la saison des fêtes au Québec, Montréal, Boréal, 2006.

Additional DocumentsSome documents require an additional plugin to be consulted

Images

-

« Desserts pour les F

« Desserts pour les F

êtes », 1902 ... -

Carte de voeux de Noë

Carte de voeux de Noë

l, 1906 -

Carte de voeux de Noë

Carte de voeux de Noë

l, 1906 -

Carte de voeux de Noë

Carte de voeux de Noë

l, 1906

-

Carte de voeux de Noë

Carte de voeux de Noë

l, 1906 -

Carte de voeux de Noë

Carte de voeux de Noë

l, 1906 -

Carte de voeux de Noë

Carte de voeux de Noë

l, 1906 -

Étalage de gâteaux de

Étalage de gâteaux de

Noël chez Stei...

-

L'arbre de Noël : la

L'arbre de Noël : la

distribution fa... -

Page couverture du ca

Page couverture du ca

talogue de Noël... -

Page couverture du ca

Page couverture du ca

talogue de Noël... -

Page couverture du ca

Page couverture du ca

talogue de Noël...

Vidéos

Documents sonores

Documents PDF

-

« Hier et demain, un conte de Noël pour le grand monde », 1889

« Hier et demain, un conte de Noël pour le grand monde », 1889

-

Publicités associées à Noël dans Le Canard, journal satirique québécois du XIXe siècle

Publicités associées à Noël dans Le Canard, journal satirique québécois du XIXe siècle