Floral Beadwork: A Métis Cultural Heritage to Rediscover

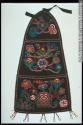

In the late 18th century, Métis women from the Great Lakes and Red River area of Manitoba sewed moccasins, tobacco pouches, saddles, gloves and clothes decorated with bright colourful beads and silks that caught the eye of travelers. These imaginative women would develop a distinctive floral design that would become the most widely used style among the Métis throughout the 19th century. Natives referred to them as the "Flower Beadwork People" because of this style. In developing this trademark style, the Métis women have given Canadians a piece of unique cultural heritage. Although this art has long been forgotten and most still know very little about it today, there remain a few collections in museums that display some of these hand worked items, namely the James Carnegie Collection(9th Earl of Southesk), which is on display at the Royal Alberta Museum in Edmonton. As they once did in the past, the Métis women of today still create and sell clothing and objects. It allows them to gain more economic independence within the community and enables them to better support their families.

A Distinctive Art Form

In the 1820s Métis women still used the geometric designs of their Aboriginal ancestors, but with time they began to prefer floral designs. According to the accounts offered by Cree people as reported by anthropologist David Mandelbaum in 1934-35, the First Nations People saw this art form as distinctively Métis: "In my youth, I had rarely seen beadwork. Back then, most decorations were made using porcupine quills. We never used floral designs-there were only geometric designs. Floral designs came to us from the Métis" (NOTE 1). But with time, the First Nations began to adopt the designs as well.

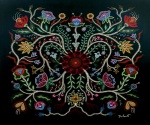

Today, gloves and vests in this style are still sold in Western Canada. Contemporary artists such as Christi Belcourt, herself of Métis origins, bring new life to this art form, using acrylic paint instead of beads, while still recreating the floral designs of yesteryear, thereby creating a link between the past and the present. The artist describes her work as follows:

In my earliest works, I began by placing a few ‘dots' in my paintings to suggest beadwork. The process has now developed to where entire floral patterns are created in ‘dots' by dipping the end of a paint brushor knitting needle into the paint and applying it onto canvas. The effect is thousands of raised dots per canvas that simulate beadwork (NOTE 2).

By developing their own style and by making large quantities of objects that were then sold or exchanged, women played an important economic role within the Western Canadian Métis nation. At the same time, they have also helped spread the cultural identity of the Métis ,a proud nation unique to Canada.

Rediscovering an Art Form

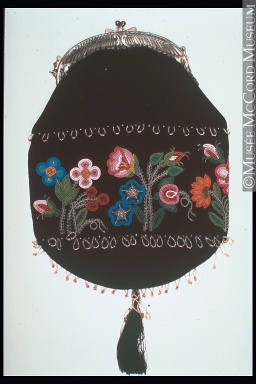

According to Ted Brasser, even though it is difficult to visit every museum and to try to identify each artefact of Métis origin, it is likely that the Métis people would have influenced Native artisans all across the Northern Plains (NOTE 3). Travelers who bought these items and clothes were looking for "genuine Indian souvenirs" and quickly forgot that they were crafted by the Métis. Such is the case of the S Black Bag, a woollen cloth bag decorated with embroidery and beads on display at the Pitt Rivers Museum at the University of Oxford. According to Laura Peers, the bag would have been purchased between 1841 and 1842 by Edward Hopkins, private secretary to George Simpson, who was the then Governor of the Hudson's Bay Company. The artefact quickly became a colonial souvenir, and so, it found a place in the museum. People supposed its tribal origin were either Cree, Ojibwa or Athabaskan, ignoring its true identity. Only recently has it been identified as a Métis artefact and with this realisation, part of its history was rediscovered (NOTE 4).

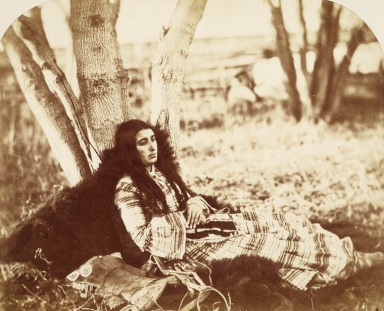

Although most museums have not documented the names of the artists, due to the writings of travelers and to a few oral reports, some embroiderers' names have escaped anonymity. Suzette Chalifoux, born in Saint Albert (Alberta) in 1866, was the child of Geneviève Campion and Paul Chalifoux, two Métis from the Lesser Slave Lake area in Alberta. She had a French education at the Couvent Saint-Albert [Convent] and worked for John Norris in Edmonton. Later, she married trapper and prospector Lewis Swift in 1897. Suzette lived in Jasper until she died in 1946. This woman made leather vests, gloves and moccasins with colourful beads and silk ornaments, which she then sold to passing travelers. Mollie Adams and Mary Schäffer, two adventurers who traveled in the Rockies in the late 19th and early 20th century, had the chance to meet this outstanding artist:

Then, Mme Swift pulled out a box from under the bed and showed us half a dozen dresses she had made herself [...].And then she showed us her fancy work [...]. She had many silk embroideries on doe skin, the softest I have ever touched. She dyed the silk herself and created her own designs [...]. There were gloves, moccasins and beautiful coats, we took everything wishing there were more [...]" (NOTE 5).

From what historians know of Suzette Chalifoux, making coats, gloves and moccasins ensured her family's survival. Thus, by sewing clothes, many Métis women apparently played an essential economic role for the well being of many a Western Canadian family. When times were hard, they often were the only ones to bring home money or necessities they had received in exchange for their work. Sadly, this was greatly overlooked by historians and anthropologists as they did their work: today only a few lines on this important heritage can be found in the literature of the 19th and early 20th centuries.

Sewing for a Living

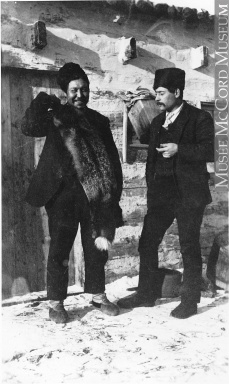

Métis women did not sew solely to clothe their families, their sewing also benefited the men in trading posts, as well as many passing travelers heading west. These women were essential to the fur trade industry, for they did not only serve as companions (and mates) to the men, but they also worked as much needed labourers to convert meat into pemmican and skins into clothing (NOTE 6). In fact, they were genuine seamstresses, since they sewed the gloves, hats, leggings, moccasins and coats that men wore as everyday clothes in their community and when working in the trading posts. These Métis women sometimes even traveled with expeditions, such as Sir John Franklin's Arctic expedition, to wash, sew and mend clothes (NOTE 7).

Their work was also prized by those who traveled to Western Canada because the style of the clothing took its inspiration from both Native and European traditions. Sometimes the demand was such that travelers had a hard time getting their clothing finished on time. The names of a few of these women, such as Charlotte Sauvé, Nancy Labombarde (née Kipling) and Marie Rose Delorme Smith, are still well known today, their work of such good quality that their names are mentioned in a few writings (NOTE 8). While most of the clothing, such as the blue capotes (that, incidentally, cannot be found in any museum), were made to be worn, some leather coats were made solely to be displayed in museums. After 1870, the women started to prefer working with imported fabrics instead of leather. Moreover, it is not uncommon that they sought to meet the needs and stylistic demands oftheir customers (NOTE 9). Although some visitors were surprised by Métis dress at first, they were quickly won over by the local style and finally adopted it. Such was the case of George Winship who, in 1867, professed to dislike the Red River style, but who eventually became very fond of it (NOTE 10).

Leather and Fabric Decoration

Before they could decorate the skins, women had to prepare them. They would soak the skins in water and remove the hair afterwards. Then, they would stretch the skin on a frame so it would dry properly. To "pluck the skins", Métis women used pieces of knife blades, iron hoops, chisels [...] that they would properly secure to handles or buffalo ribs, soas to be able to better grasp the implement (NOTE 11). The women would start at the neck, the skin being thicker there, and moved from there to the rest of the body. Once this work was done the skin was white as snow, supple as a bed she etand soft as chamois (NOTE 12). Skins were then smoked to prevent them from hardening and becoming brittle. Depending on the desired colour, Métis women used either, or a mix of, willow or oak based solutions for tanning (willow forred and oak for brown) (NOTE 13).

During the long winter nights women made mostly moccasins or soft shoes, vests, gloves, leggings, knife or gun sheaths, tobacco pouches (such as the famous octopus bag), saddles, blankets for riding dogs, harnesses and whips. (NOTE 14) They drew their inspiration for their designs from Prairie flowers, St. Boniface Cathedral's rose window or from designs they had come upon by chance, but the most common designs are the five pointed star and colourful spring flowers (complete with the stem, leaves and flowers). To sew these designs women used needles, beads silk and thread they bought at the Hudson's Bay Company or in general stores (NOTE 15). Porcupine quills, painted in different shades then embroidered on mittens or moccasins and the tail hairs of white or grey horses were used as decorations. The floral patterns were generally embroidered on leather, but also on black or dark blue wool sheets or on stroud, a red coarse wool fabric; bags and leggings were lined with cotton (NOTE 16). With time, sewing machines became a necessity for making clothing.

When they were short on material, women adapted their techniques. According to Sherry Farrell Racette, "when supplies of silk and beads ran low during World War One, Madeleine Bouvier Laferte and her daughter-in-law adapted the tufting technique (which they had learned in the convent) from wool to moose and caribou hair" (NOTE 17). A certain Sister Leduc would have received a few instructions from Madam Laferte and then would have decided to include this technique in the curriculum of the boarding school where she taught. And so, this is how tufting using caribou and moose hair would have spread throughout the Northwest Territories. Today, scholars believe such exchanges were likely reciprocal, although previous studies mostly talked about the sisters' influence over Métis women, in so far as they would teach some needle point techniques to the young women.

Nonetheless, it is undeniable that the education offered in the convents of Montreal and in Western Canada had had an important role to play in the preservation of this cultural custom, since sewing was at the center of a young women's education at the time. This is equally true for both Catholic and Protestant schools. For the Sœurs Grises [Grey Nuns] of Saint-Boniface, learning how to sew was a priority since, at the time, it was believed that women needed to know how to sew if they wanted to be a good wife and mother. Yet, not all the girls received a formal education and knowledge was often passed on from mother to daughter or from grandmother to granddaughter. Marie Rose Delorme's case is interesting because, although she spent four years in the Saint-Boniface Convent, she says she owes her artistic talents to her mother's influence (NOTE 18).

An Essential Heritage

The works of these Métis artists area proof of their contribution to the economic life of the community in Western Canada. Their talents allowed them to express their identity as individuals and as a community, "putting the bodies of the men to good use", as Sherry Farrell Racette once put it (NOTE 19). If some people see sewing as a second-class occupation, they should be reminded that Métis women put it to good use, thanks to their imagination and work, to ensure the survival of their families all throughout the 19th and 20th centuries.

Nathalie Kermoal

Associate Professor

University of Alberta's Faculty of Native Studies and Campus Saint-Jean

NOTES

Note 1. Saskatchewan Archives Board, David Mandelbaum Field Notes (1934), Notebook 2, R-875.

Note 2. See Christi Belcourt's Website: http://www.belcourt.net/

Note 3. Nathalie Kermoal, Un Passé Métis au Féminin, Québec, Les Éditions GID, 2006, p. 219.

Note 4. Laura Peers, "Many Tender Ties: The Shifting Contexts and Meanings of the S BlackBag", World Archeology, Vol. 31 (2), 1999, p. 288.

Note 5. Colleen Skidmore, This Wild Spirit: Women in the Rocky Mountains of Canada, Edmonton, University of Alberta Press, p. 8.

Note 6. According to Paul Kane, in the 1840s, women's work in Fort Edmonton "consist[ed] of making moccasins and clothing for the men and converting the dried meat into pemmican". Paul Kane, Wanderings of an Artist, Edmonton, Hurtig, 1968, p.93.

Note 7. Sherry Farrell Racette, "Sewing for a Living: The Commodification of Métis Women's Artistic Production" in Katie Pickles and Myra Rutherdale (ed.), Contact Zones: Aboriginal and Settler Women in Canada's Colonial Past, Vancouver, UBC Press, 2005, p. 25.

Note 8. Sherry Farrell Racette, "Sewing for a Living ...", p. 31 and p. 37.

Note 9. Kermoal, op. cit., p. 222.

Note 10. "Before many months passed I was attired much the same as they [the Métis] including moccasins ... red sash and capeaux" Archives of Manitoba, George Winship (1914), My First Float Ride Down the Red River, and Incidents Connected Therewith, p. 6, MG3 B15.

Note 11. Guillaume Charette, L'Espace de Louis Goulet, Winnipeg, Editions Bois-Brûlés, 1975, p. 73.

Note 12. Charette, op. cit., p. 67.

Note 13. Kermoal, op. cit., p. 217. À

Note 14. Ibid. p. 222.

Note 15. Ibid., p. 223.

Note 16. Ibid., p. 223.

Note 17. Sherry Farrell Racette, "Beads, Silks and Quills: The Clothing and Decorative Arts of the Métis", p. 183.

Note 18. Sherry Farrell Racette, "Sewing for a Living ...", p. 22.

Note 19. Ibid., p. 42.

Archives provinciales du Manitoba, George Winship (1914), My First Float Ride Down the Red River, and incidents Connected Therewith, MG3 B15.

Carpenter, Jock, Fifty Dollar Bride : Marie Rose Smith - A Chronicle of Métis Life in the 19th Century, Hanna, Gorman & Groman Ltd., 1977, 160 p.

Charette, Guillaume, L'espace de Louis Goulet ,Winnipeg, Editions Bois-Brûlés, 1975, 204 p.

Harrison, Julia D., "The Great White Coverup", Native Studies Review, Vol. 3, no. 2 (1987), pp. 47-59.

Kane, Paul, Wanderings of an Artist, Edmonton, Hurtig, 1968, 329 p.

Kermoal, Nathalie, Un passé métis au féminin, Québec, Les Éditions GID, 2006, 269 p.

Peers, Laura, "‘Many Tender Ties': The Shifting Contexts and Meanings of the S Black Bag", World Archeology, Vol. 31 (2), 1999, pp. 288-302.

Saskatchewan Archives Board, David Mandelbaum Field Notes (1934), Notebook 2, R-875.

Racette, Sherry Farrell, "Sewing for a Living: The Commodification of Métis Women's Artistic Production" dans Katie Pickles et Myra Rutherdale (ed.), Contact Zones : Aboriginal and Settler Women in Canada's Colonial Past, Vancouver, UBC Press, 2005, pp. 17-46.

Racette, Sherry Farrell, "Beads, Silks and Quills: The Clothing and Decorative Arts of the Métis" dans Lawrence Barkwell, Leah Dorion et Darren Préfontaine (ed.), Métis Legacy: A Métis Historiography and Annotated Bibliography, Winnipeg, Pemmican Publication Inc., 2003, p.181-188.

Skidmore, Colleen, This Wild Spirit: Women in the Rocky Mountains of Canada, Edmonton, University of Alberta Press, 475 p.

Additional DocumentsSome documents require an additional plugin to be consulted

Images

Hyperliens

- Site de l'artiste métisse Christi Belcourt

- Sacs métis brodés - Musée canadien des civilisations

- Manteau en peau de chevreuil de Louis Riel, avec broderies florales

- Veste Métis en peau de caribou brodée, Alberta, 1905. Confectionnée par Flora Loutit