Van Horne Mansion (1870-1973): a Demolition That Changed the History of Heritage Preservation

par Drouin, Martin

Heritage enthusiasts looking for the Van Horne Mansion on rue Sherbrooke in Montreal will be disappointed. On the land where it was built during the middle half of the 19th century now stands a17-floor skyscraper. However, what is important about the Victorian-era home is not so much its material value, but rather the debate that surrounded its demolition in 1973. It was a moment that marked the city's transition to a modern metropolis and it changed the way people thought about their past and their future. It was a time that solidified the role of heritage conservation organisations and transformed people's idea of what constituted heritage in Quebec.

Article disponible en français : Maison Van Horne (1870-1973) : une destruction fondatrice

The Transformation of Downtown Montreal

The modernisation movement that followed the end of World War II had a significant impact on the City of Montreal. Both urban planning and landscaping in the city went through a massive transformation. Although the city had been undergoing changes before, the post-war period was particularly active in this regard. Many large-scale projects were started during this time. The business district, which was historically located in the area now known as "Old Montreal", was moved northwest as skyscrapers were built that afforded more office space and the comfort of modern technology. Among the new buildings was Place Ville-Marie, designed by the architect I.E. Pie, which was inaugurated in 1962. With its cross-shaped layout and 42 stories, it symbolised the new Montreal, a metropolis worthy of being compared to other large international cities. This modernisation trend continued during the 1960s and 1970s.

Montreal's transformation was not without a certain degree of controversy. The transformation started in a part of the city that was urbanised during the second half of the 19th century. The "New Montreal" posed a threat for the old one and many residents wondered about its survival. The Van Horne Mansion was one of many upper-class homes built during the same period that would eventually disappear because of modern construction. The homes that were demolished included those belonging to: Hugh Allan (1943), Ogilvie (1944), Workman (1952), R. G. Reid (1956), Fred Molson (1957), Richard B. Angus (1957) and Hector Mackenzie (1960). These important names in finance, business and industry had gathered in the same area at the southern foot of Mount Royal, located just outside of downtown. This area was known as the Golden Square Mile. At the beginning of the 1970s, most of the owners had left the area and moved to Westmount, a growing upper-class neighbourhood. It is not surprising that, when Van Horne's heiress died in 1967, the successor wanted to sell the home. The reasons stated were the high cost for its upkeep and the changes being made to rue Sherbrooke.

Organised Protests

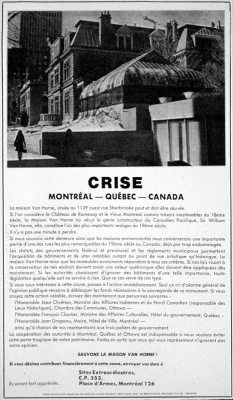

A suitable offer was made in 1973. Promoter, David Azrieli, who had been active in the Montreal construction industry since 1950, wanted to buy the property to build an office tower. The building's strategic location in the heart of the new downtown core interested him more than the hundred-year old building itself. Hence, his purchase of the land was established under condition of having the right to demolish the mansion. Between the months of May and September, there was a media storm fed by the debate between heritage protection advocates and those pushing for development. Most of the other homes in the area had been demolished with relative indifference. However, the Van Horne Mansion was different. The arguments made by residents in its defence would make history and greatly influence heritage conservation in Quebec.

The developer's request was eventually granted. The Jacques-Viger Commission (an organisation responsible for monitoring (overseeing) development in the historic districts of Old Montreal and other important sites across the city) was against the building's demolition. Despite this, the City of Montreal's permit agency saw no legal objections. By mid-April authorisation was granted to demolish the building. The Commission de Biens Culturels du Québec [Cultural Assets Board] subsequently requested action from the provincial government. The commission requested that the Ministère des Affaires Culturelles send a notice of their intention to consider the Mansion as an official heritage site in order to stop the demolition. However, after reviewing the request ,five weeks later, the ministry felt obliged to refuse it despite the commission's constant pressure. Meanwhile, because they were waiting for the official report from the ministry, Montreal's permits agency was forced to delay processing the developer's application. Then, with no further possible action to be taken, the permit was finally issued. Several hours later, workers tore apart the inside of the building. The following day, on Saturday the 8th of September, 1973, the Van Horne Mansion was levelled to the ground.

Three months earlier, a campaign to save the mansion had been organised. Groups protested against the ministry's decision tor etract their intended proposal to recognise the mansion as an official heritage site. This was the first time that Montreal residents really became aware of the imminent disappearance of the mansion. As a result, the Society for the Protection of Great Places was especially created to stop the demolition of the mansion. The head of the organisation was James MacLellan, who presented himself as an ordinary Montreal resident who would personally suffer irreparable loss if the Van Horne Mansion were destroyed. For the first time in the history of the city, he brought his case to court challenging the notion that the Mansion was simply a private residence, claiming that it was, in fact, necessary to the well being of the general public. He had many supporters, but his challenge was finally dismissed. In addition to the many citizens and history and heritage experts that sent letters of protest and journalists who gave the public a voice, many organisations also sided with protesters. These organisations included: the Royal Architectural Institute of Canada, the Association des Architectes de la Province de Québec, the Société d'Architecture de Montréal and the Heritage Canada Foundation among others. A broader vision of heritage was developing and changing the previous global conception of what constituted national heritage.

The Definition of Heritage Conservation

The hotly debated situation raised the question as to why the Van Horne Mansion should be saved. The question was in the headlines and was the subject of many articles published in 1973. First and foremost, the building bore the name of its most famous owner, William Cornelius Van Horne (1843-1915), who had once had one of the biggest fortunes in Montreal at the time. His time as the head of Canadian Pacific saw the construction of the first railway line all the way to the Pacific Ocean. He also established economic ties between Vancouver and Hong Kong and oversaw the construction of several hotels owned by the company, which included Banff Springs Hotel in Lac Louise (Alberta) and Château Frontenac in Quebec City. He also supervised railway constructionin Cuba. Van Horne was also an avid art collector and a member of the Art Association of Montreal, predecessor of the Musée des Beaux-Arts de Montréal. In fact, he left his first Montreal residence, Shaughnessy House, which he had moved into in 1882, in order to display his growing art collection. He had works by Rembrant, El Greco, Rubens, Goya, to name a few. The Shaughnessy house is now owned by the Canadian Centre for Architecture.

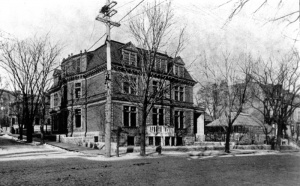

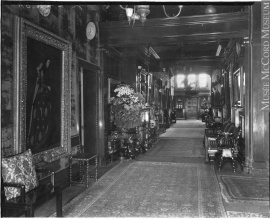

In 1890, Van Horne, bought the residence on the corner of rue Sherbrooke and rue Stanley. The house was formerly owned by John Hamilton (1827-1888), a businessman, financier, and politician. The architect of the house, built in 1870, is unknown. However is often thought to have been John W. Hopkins (1825-1905) who was very active in Montreal during the second half of the 19th century. In any case, it is not the house's initial construction that conservationists saw as the main reason for saving it, but rather the expansion work that was done afterwards. After buying the residence, Van Horne gave the remodelling contract to Edward Colonna (1842-1948), who had just opened an office in Montreal. Colonna had previously worked in New York for the decorator Louis C. Tiffany (1848-1933) and the architect Bruce Price (1845-1903). Colonna (of Belgian origin) was considered to be one the pioneers of Art Nouveau in North America. The inside of the Van Horne Mansion is a mixture of Art Nouveau and Victorian influence. With its large greenhouse, the house was considered to be a veritable North American palace.

In order to bring attention to the historical value of the Mansion, the safeguarding campaign used the residence's huge art collection as one of its main arguments. In fact, it had one the biggest private art collections in the world at the turn of the 20th century. The mansion also reflected the fundamental role that Van Horne played in the construction of the Canadian railway. Through its art collection and its design, the house served as a reminder of the extravagant era of the Golden Square Mile. The collection and interior design of the building were prime examples of the beginnings of Art Nouveau in North America. In reaction to conservation efforts, the opponents to the safeguarding campaign claimed that they did not understand how Victorian architecture could be considered as being typically Canadian or from Quebec. The Mansion was in fact a mix of various styles. As for William Cornelius Van Horne, he was born in the United States, where he was also buried. He helped to build Canada through the construction of the Trans-Canadian railroad. Therefore, according to the Ministre des Affaires Culturelles, the mansion was not a "typical piece of Quebec architecture."

The Van Horne Mansion debate also raised broader questions about Quebec culture. First of all, it pitted English and French-speaking communities against one another. Was the campaign to save the mansion just a cause important to Montreal English speakers? Could French speakers actually identify with historic characters such as Van Horne? Was his legacy important to them? Who should the Ministre des Affaires Culturelles listen to? Those campaigning for the mansion's protection questioned the cultural references of what constituted heritage in Quebec. Was Quebec heritage only the product of the French colonists and immigrants or should heritage from other peoplegroups be considered? French architecture from the 17th and 18thcenturies was already thought to be an essential component of Quebec heritage. Should 18th century architecture (which radically transformed Montreal and coincided with a rise in power of English-speaking Canadians) be preserved? In a way, the Van Horne Mansion had to be sacrificed in order for these questions to be raised and answered.

The Impact of the Mansion's Disappearance

The day after its demolition, the Van Horne Mansion was on the front page of every paper in Montreal. The campaign to save the Mansion may have finished in failure, but the eight-month media storm that followed was not without benefits. Articles, editorials, letters to the editor, advertisements and documentaries informed the population about what had happened to the Van Horne Mansion. At first it was just Montreal residents, and then the entire province of Quebec came to learn about the history and heritage of the famous building. Heritage conservationists would eventually succeed in using the media to convince the population that their opinion in the conflict was important. Their message was addressed to a broad population through a constant flow of communication in one form of media or another. They described the history of the lost building, explaining its architecture and why it was important. Since that time, the role of media in the protection of heritage has continued to increase and take its place in society. Today, it has become commonplace that, anytime an important building or place of any kind is threatened, press releases and letters to journalists are sent out for widespread distribution. In addition, today, journalists dedicate more time to covering this type of debate.

Defenders of architecture and Montreal heritage of the Van Horne Mansion were far from deterred by it's demolition. On October of 1973, one month after the house was demolished, citizens' groups came together under the banner "Sauvons Montréal". This federation would grow rapidly from only a dozen participating groups, to twenty, and then to over thirty groups. The federation spawned a variety of causes as its numbers increased.

In addition to its architectural and heritage conservation mission, the federation took on many other causes as various new groups of citizens joined the organisation. Their projects included housing, building renovation and environmental causes. The old concept of "historical monument" was coupled with the notion of "cultural heritage". In addition to these conservationist concepts was the emerging concept of "urban heritage", which would eventually become an entirely fresh way of looking at the city's heritage. As for the Van Horne Mansion, it would become the symbol of an on-going battle to preserve the essential character of the city. On the date of the first anniversary of its demolition, Montreal residents came together, candles in hand, to remember the events surrounding its destruction. Subsequently, the day of the anniversary became a time to remember the importance of the vigilance of common citizens.

No public apology was made. However, several things had changed. An amendment was made to article 426 of the Cities and Towns Act and another was made to article 392 of the Municipal Code of Quebec. As a result, if an application for official heritage recognition is made to the provincial government, the issuing of a demolition permit could be delayed up to one year. Four months after the events, three buildings adjacent to the site of the Van Horne Mansion received official recognition as well as a forth building on the opposite side of rue Sherbrooke. The buildings were built during the same period as the Van Horne Mansion and were representative of Victorian-era architecture. These 19th century buildings included: the United Services club, Mount Royal Club, Corby House and the Atholstan House. After the demolition of the Van Horne Mansion, the number of officially recognised heritage sites grew exponentially. Buildings that were recognised were not only located in Old Montreal and were not only representative of the 17th and 18th centuries. From that time forward, there existed a more inclusive view of heritage in Quebec.

Martin Drouin

Associate Professor, Département d'Études Urbaines et Touristiques, UQAM

Coordinator of the Institut du Patrimoine, UQAM

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Carreau, Serge et Perla Serfaty (dir.), Le patrimoine de Montréal : document de référence, Montréal, Ministère de la Culture et des Communications/Ville de Montréal, 1998, 168 p.

D'Iberville-Moreau, Luc, "Pourquoi faut-il sauver la maison Van Horne ?", Le Devoir, 1er septembre 1973, p. 13

Drouin, Martin, Le combat du patrimoine à Montréal (1973-2003), Québec, Presses de l'Université du Québec, 2005, 386 p.

Fish, Michael, "La démolition des œuvres de Sir Van Horne : une tragédie culturelle et historique", Le Devoir, 27 juillet 1973, p. 4.

Gabeline, Donna, Dane Lanken et Gordon Pape, Montreal at the Crossroads, Montréal, Harvest House, 1975, 220 p.

Gournay, Isabelle et France Vanlaethem (Dir.), Montréal Métropole, 1880-1930, Montréal, Centre Canadien d'Architecture, 224 p.

Knowles, Valerie, From Telegrapher to Titan - The Life of William C. Van Horne, Toronto, Dundurn Press, 2004, 501 p.

Linteau, Paul-André, Histoire de Montréal depuis la Confédération, Montréal, Boréal, 2000 [2e édition], 627 p.

Marsan, Jean-Claude, Montréal en évolution : historique du développement de l'architecture et de l'environnement urbain montréalais, Montréal, Méridien, 1994 [2e édition], 515 p.

Rémillard, François et Brian Merrett, Demeures bourgeoises de Montréal, le Mille carré doré, 1850-1930, Montréal, édition du Méridien, 1986, 242 p.

Additional DocumentsSome documents require an additional plugin to be consulted

Images

-

« The structure wich

« The structure wich

will replace th... -

Bibliothèque, résiden

Bibliothèque, résiden

ce Van Horne, M... -

Édifice du 1155 rue S

Édifice du 1155 rue S

herbrooke Ouest... -

Édifice du Mount Roya

Édifice du Mount Roya

l Club, Maison ...

-

Résidence de Van Horn

Résidence de Van Horn

e, rue Sherbroo... -

Sir William Van Horne

Sir William Van Horne

, dirigeant du ... -

Sir William Van Horne

Sir William Van Horne

, Montréal, QC,... -

Vivoir, résidence Van

Vivoir, résidence Van

Horne, Montréa...