Saint Louis Forts and Châteaux National Historic Site (Quebec City)

The Saint-Louis Forts and Châteaux Historic site is located on the top of a cliff overlooking the lower-town of Quebec City. It is close to the Fairmont hotel, Château Frontenac, and lays covered beneath the boardwalk of Dufferin Terrace. It is a major archaeological site that has vestiges linked with most of the governors of the French regime and the majority the British governors of the colonial period. However, despite this fact, it was only recently in 2001 that it was recognised as a National Historic Site. After a campaign of successful archaeological digs carried out by Canada Parks between 2005 and 2007, the site was opened in 2008 to the public during the 400th anniversary celebrations of Quebec City. More than 300,000 people visited the vestiges of the Saint-Louis Châteaux, an exceptional piece of heritage worthy of public appreciation.

Article disponible en français : Forts et châteaux Saint-Louis (Québec)

The Rise and Fall of the Site's Heritage Value

The last Château Saint-Louis fell victim to a fire in 1834. After the disaster, only a few architectural vestiges remained to remind the population that it was once the seat of the colony's government. A short distance from the remains was the Château Haldimand, which was built in the 1780s. There was also an explosive magazine storage dating back to the French regime (1685) and several secondary buildings built during the English regime. Together, these buildings were among the only few reminders of the location's colonial era. The construction of the Durham Terrace in 1838 and its expansion in 1854 would hide all the remains of the Château Saint-Louis. This construction thus accelerated the transformation of the area into a popular public boardwalk (NOTE 1).

In 1892, the construction of the Château Frontenac would revive interest in protecting the Château Haldimand and the explosive magazine storage facility. In fact, the building process would require them to be demolished. The conservation campaign, although it was led by several influential citizens, would fail in reaching the objective of safeguarding the location, thereby allowing the buildings to be demolished (NOTE 2). The choice of the term "château" in the name of the prestigious hotel (which was named after a famous French governor, Comte de Frontenac) nevertheless helped to maintain the memory of the lost Château Saint-Louis.

On the 21st of September, 1898, a monument paying tribute to Samuel de Champlain was officially inaugurated. The monument, built as an initiative of the Société Saint-Jean-Baptiste, was located at the east end of the Dufferin Terrace. This was, in fact, just inside of the old wall of the first Fort Saint-Louis, which Champlain had built in 1620. This emphasised not only the importance of Champlain, but also the prestige of the place he helped build. In July, 1908, at the base of the Champlain monument, the 300th anniversary celebrations of the foundation of Quebec took place. In 1912, Ernest Gagnon, a historian, published an impressive piece of work called "Le Fort et le Château Saint-Louis, Québec - Étude Archéologique et Historique" [The Saint-Louis Chateau and Fort, Quebec City; a Historical and Archaeological Study]. His book, written in a rather romantic tone, recounts the history of the Saint-Louis Forts and Châteaux (NOTE3).

Thereafter, the prestigious vestiges hidden under the Dufferin Terrace would largely be forgotten. Several more decades would pass before they eventually would get the attention they deserve.

The Historical Account

Samuel de Champlain built Fort Saint-Louis at the summit of cap Diamant in 1620. This location offered excellent natural defences on three sides. However, the small wooden fort soon became inadequate and Champlain had to order the construction of new defences in 1626. Consequently, stone housing was built inside the inner walls of this second fort.

The first governor of New France, Charles Huault de Montmagny, arrived in Quebec City in 1636. Aware of the strategic importance of Fort Saint-Louis, he quickly had the ramparts reinforced with stone (NOTE 4) in place of the wood enfences originally built by Champlain's men. This work was however not finished until several decades later. Montmagny oversaw the construction of a new residence, the first Château Saint-Louis, finished in 1648. It was a single-level stone building (26.2 metres x 7.3 metres [86 x 24 feet]) covered in a shingled roof. The building was subsequently expanded at the beginning of the 1680s.

The layout of the Saint-Louis Fort and Château would change only slightly over the decades that followed with small changes made by governors between 1648 and 1689. Then, during the second tour of office of Louis de Buade, Comte de Frontenac, major changes were made. After the siege of Quebec City by admiral Phips in 1690, Frontenac had a battery of 17 canons installed south of the château. He also ordered the reconstruction of Fort Saint-Louis and almost quadrupled its size. The new fort made use of fortification principles perfected by French military engineer Vauban(NOTE5).

Then, in 1694, the governor made plans for a new Château Saint-Louis that would be suitable to receive the King of France if he chose to visit the colony. The building would be 36 metres long with two levels. It would have a central hall and two wings, one at each extremity, covered with a slate roof. Unfortunately, due to a lack of financing, Frontenac was unable to complete the construction. The building was completed 30 years later, in 1723, under the rule of the Marquis de Vaudreuil. Besides the south wing, which had already been finished at the time, two additional wings would be built each end of the building.

The violent bombardments of the battles of the summer of 1759 greatly undermined the structural integrity of the Saint-Louis Fort and Château. The north wing and the terrace overlooking the river were so damaged that they finally had to be demolished. The British authoritie srestored the rest of the building between 1765 and 1768. As for the terrace, it would take ten years before it was finally rebuilt.

At the end of the 1780s, the construction of the temporary citadel marked the end of the era of Fort Saint-Louis' use as defensive stronghold. Château Saint-Louis was too cramped for the needs of administrative services and too small to receive the representatives of the British monarch. Governor Haldimand thus started the construction of a new official residence, Château Haldimand, which was built between 1784 and 1787. However, at the end of the first decade in the 19th century, the new governor, James Craig, decided to reintegrate the Château Saint-Louis into the new structure.

The Château Saint-Louis was raised one floor and expanded towards the front. The architecture of the château adopted a Palladian style, which was very popular in England at the time. For example, it had triangular gables decorated with oculi (eye-shaped openings), a porch with rows of columns, and Palladian windows. The front entrance of the building had alarge beautiful window over the doors. As well, not unlike large English estates at the time, numerous secondary buildings were built in the court in order to add to the comfort of the governor (e.g., bakery, kitchen, laundry house, greenhouse, ice-house, stables, sheds, etc.)

The building was victim of a fire on the night of January 23rd, 1834. The building burned completely to the ground and was never rebuilt. In 1838, a large terrace was built on the site called the Durham Terrace. The terrace and its successive expansions greatly contributed to the protection of the archaeological ruins of the four forts and the two châteaux Saint-Louis. The ruins were excavated in the 1980s, 90s and in the first decade of 21st century.

A Major Archaeological Site

More than 500 archaeological vestiges have been refurbished and more than 500,000 artefacts have been found during digs that took place from 2005 and 2007. Archaeologists also revealed the ruins of several defensive structures related to the four successive Saint-Louis forts. The ruins revealed were those of the fort constructed by Champlain in 1620, as well as the fort constructed by Frontenac at the beginning of the 1690s. The ruins included: the canton [a type of corner masonry] of the first fort (1620-1626), the stone steps and wooden cannon platform of the second fort (1626-1635), the redoubt, and parts of the stone walls of the third (1636-1690) and fourth forts (1691-1834). The vestiges of the eight cannon platforms of the battery from the 1691 château were also discovered. Some of the ruins still show signs of the 1759 bombardment. Several projectiles were found on the site. Evidence of the repairs, carried out by the British military after 1760, was also found on the walls of the fort. Even today it is easy to identify the remains of the two Saint-Louis châteaux on the site. The vestiges of the first château, built by Governor Charles Huault de Montmagny from 1647 to 1648, were partly integrated into the building that was started by Frontenac in 1694 and finished by Vaudreuil in 1723. All the remainsof the basement of this residence were refurbished during the digs, except fortwo which are currently located underneath the funicular on Dufferin Terrace. The remains of the two wings of the building, located at the north and southwest extremities of the residence, were also refurbished. The digs in the basement revealed three pits that contained numerous artefacts from the British and French regimes indicating how daily life was for the governors of various eras. Several parts of the basement were linked to the kitchens of the château (e.g., kitchen, pantry). The remains of a large bread oven, a hearth, and a fireplace were also exposed. Nearly three metres of the original basement walls were preserved. In some cases the remnants of the original vaults, which separated the basement and the ground floor, are visible.

The expansion work done between 1808 and 1811 left behind many clues for archaeologists to discover. These include the foundationsof the staircase and of the entrance hall, two hallways for staff and the walls of the southwest wing, which was expanded at the time. Pieces of limestone that paved the paths and French-era wooden floors were also discovered. In addition, archaeologists discovered sandstone tiles from the English regime in all the basement rooms of the building.

The official residence of the King's representative to the colony was surrounded by many smaller buildings that provided services for the governor and his staff. The vestiges of many secondary buildings and structures are still located underneath the Dufferin Terrace. These include vestiges dating back to the British regime (e.g., front court, wood shed, garage, stables, ice-house, greenhouses, covered passageway, kitchen, etc.)

Drainage was a constant concern for colonial authorities because the Château Saint-Louis was built on the edge of a cliff and streams naturally converged at that point. For that reason, many successive drainage systems were built. These systems were intended to drain sewage and rain water away from both the Saint-Louis and Haldimand Châteaux. Many elements of these old systems have been excavated and refurbished by archaeologists.

There are very few remains of the first DurhamTerrace. The Terrace rested on the base of the old walls of the Château Saint-Louis that had burned four years earlier. The only original element that remains is the retaining wall at the south end of the château. Two stone walls, which were built in the old south court of the château, are evidence of the terrace's expansion in 1854. Twenty-five years later, a new terrace was built bearing the name of Lord Dufferin, as it is known to this day. The present-day front wall of the Dufferin Terrace is the same as those built in 1879, 1887, and 1889.

A Site of Exceptional Heritage Value

Several factors contribute to Saint-Louis Forts and Châteaux Historic Site's heritage value. First, the fact that each fort was built in the same place at the edge of the cliff confirms that Champlain's choice of the site was significantly important. It was a key aspect in the defence of the colonial city in the 17th century. The official colonial residence that was subsequently built on the site also served as an important symbol, particularly because it overlooked the Saint-Lawrence River, the port of entry to the rest of the colony. It was the site that housed governors for more than 200 years in two different buildings, the Châteaux Saint-Louis and the Château Haldimand. Champlain's choice of location would not be changed by neither his French nor his British successors (governors). In fact, there is no other place in Canada with such a strong tie to the executive power of the colonial era. The location of Fort Saint-Louis was also an influential factor in the urban development of the city since the first roads created all converged on the same location. These elements are noticeable even today in the case of the streets rue Saint-Louis and rue Sainte-Anne.

The Saint-Louis Forts and Châteaux National Historic Site, officially inaugerated in 2001, played an essential role in the foundation of Quebec City. This is also the case of Place Royale (Champlain's settlement), the palace of the Intendant of New France (additional major archaeological vestiges in Quebec City), the Cartier-Brébeuf National Historic Site and the Cartier-Roberval site in Cap-Rouge.

At the time when it served as the governor's residence, the social elite were the site's first visitors. They included government and military officials as well as religious figures. Then, with the construction of the Durham and Dufferin Terraces, the site became a popular gathering place for residents of the city and for people from around the world.The fact that the terraces were built there speaks volumes for the exceptional beauty of the location. From the terrace, visitors have a view of the Saint-Lawrence River, the river's north and south banks and Île d'Orléans. For more than 100 years, the iconic hotel, Château Frontenac, has added even more prestige to the site. Quebec City's historical districts were then added to the official list of UNESCO world heritage sites in 1985. The official inscription commemorating this event is engraved on Champlain's monument next to Château Frontenac.

In 2008, a commemorative plaque was placed close tothe Kiosque Frontenac [Stand] and the funicular recalling the history of the Saint-Louis Forts and Châteaux. The plaque was unveiled on the occasion of the 400th anniversary celebrations of the foundation of Quebec City. It was at this time that the general public was first given access to the ruins, which had previously been covered by the Dufferin Terrace.

Jacques Guimont

Archaeologist

Parks Canada

NOTES

Note 1: At the end of the 1870s, the Durham Terrace was again expanded to the dimensions of the present-day terrace. Today's terrace bears the name of Lord Dufferin, who was then governor-general of Canada. The reconstruction of the Château Saint-Louis was a project that was very important to him, although it would never be built.

Note 2: The Château Haldimand served as a residence for British governors between 1787 and 1811. The explosive magazine was built according to the plans of the engineer Robert de Villeneuve in 1685.

Note 3: One must also mention Pierre-Georges Roy, the historian and archivist who wrote the Bulletin des Recherches Historiques in 1895, to which he dedicated a large part of his life. In it, he published numerous documents dealing with the site of the Saint-Louis Forts and Châteaux.

Note 4: The French word rempart means a mass of earth that protects the area behind it. It is not exactly a work of masonry in itself. The mass of earth can, however, fortified by a work of masonry or by a wooden encasement or palisade. This work of masonry is called a "revêtement" [or covering] in French. This is the case with Quebec City's fortifications. These revêtements are stone walls, such as those present at Saint John, Kent or at the Saint-Louis Gates in Old Quebec. Behind the stone covering is the mass of earth that is actually what is called the rempart. This is wherethe name "remparts de Québec" comes from.

Note 5: Sébastien Le Prestre Vauban (1633-1707) is the most famous French military engineer of the 17th century. He is credited with perfecting the fortified wall, otherwise known as the "fortification bastionnée" in French. The fortified walls in Quebec City are an excellent example of the application of the principles he developed.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Ethnotech inc. (Christine Chartré, Jacques Guimont, Yves Laframboise et Gérald Pelletier), Évolution historique de la terrasse Dufferin et de sa zone limitrophe de 1838 à nos jours, Québec, Parcs Canada, 1981, 2 volumes (rapport interne).

Ethnotech inc. (Jacques Guimont), Étude sur l'évolution historique du secteur du Château Saint-Louis et de sa zone limitrophe de 1760 à 1838, Québec, Parcs Canada, 1983, 371 p. (rapport interne).

Guimont, Jacques (avec la collaboration de Pierre Cloutier, Michel Brassard et Paul-Gaston L'Anglais), L.H.N.C.des Forts-et-Châteaux-Saint-Louis, compte rendu de la campagne de fouilles de 2005, Québec, Parcs Canada, Centre de services du Québec, Service du Patrimoine culturel, mai 2006, 146 p. (rapport interne).

Guimont, Jacques, L.H.N.C.des Forts-et-Châteaux-Saint-Louis, campagne de fouilles de 2006; les faits saillants, Québec, Parcs Canada, Centre de services du Québec, Service du Patrimoine culturel, avril 2007, 20 p. (rapport interne).

Laurent, Jeannine et Jacques Saint-Pierre, Les forts et châteaux Saint-Louis, 1620-1760, Québec, Parcs Canada, 1982, 455 p. (rapport interne).

Parcs Canada, "Énoncé d'intégrité commémorative, Lieu historique nationaldu Canada des Fortifications-de-Québec (Québec, Québec)", Québec, Parcs Canada, Unité de Gestion de Québec, 2004

Parcs Canada, "Énoncé d'intégrité commémorative, Lieu historique national du Canada des Forts-et-Châteaux-Saint-Louis (Québec, Québec)", Québec, Parcs Canada, Unité de Gestion de Québec, 2004.

On the Balado.tv website, there are two video clips on the Forts and Châteaux Saint-Louis: "Découverte majeure en bordure du château Frontenac" and "1759 : les bombardements de Québec". They can be found at the following Web address: http://www.balado.tv

Additional DocumentsSome documents require an additional plugin to be consulted

Images

-

Danse au château St-L

Danse au château St-L

ouis, 1801 -

Ensemble de vaisselle

Ensemble de vaisselle

de table en cr... -

Ensemble de verrerie

Ensemble de verrerie

de table : verr... -

Épingle plaquée or et

Épingle plaquée or et

incrustée de t...

-

Escalier de pierre du

Escalier de pierre du

deuxième fort ... -

Fourquines (supports

Fourquines (supports

en « U » pour a... -

Fragment d’obus franç

Fragment d’obus franç

ais de 13 pouce... -

Inauguration officiel

Inauguration officiel

le de l’ouvertu...

-

Insigne aux armoiries

Insigne aux armoiries

papales en cui... -

La basse-ville de Qué

La basse-ville de Qué

bec et le châte... -

La basse-ville de Qué

La basse-ville de Qué

bec, 1778 -

Laval Normal School,

Laval Normal School,

the last piece ...

-

Le château Saint-Loui

Le château Saint-Loui

s après son reh... -

Le Fort Saint-Louis,

Le Fort Saint-Louis,

détail de la ma... -

Le four à pain et l’â

Le four à pain et l’â

tre de la cuisi... -

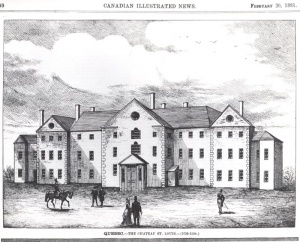

Le nouveau Château Sa

Le nouveau Château Sa

int-Louis, Québ...

-

Les fouilles de la co

Les fouilles de la co

ur sud du châte... -

Mousquetaire avec son

Mousquetaire avec son

mousquet et sa... -

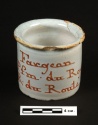

Petit pot à pommade e

Petit pot à pommade e

n faïence franç... -

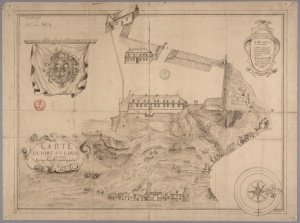

Plan du fort Saint-Lo

Plan du fort Saint-Lo

uis en 1683

-

Rangée du haut : obus

Rangée du haut : obus

anglais de 10 ... -

Un douzain de 1595

Un douzain de 1595

-

Un groupe de dignitai

Un groupe de dignitai

res visitant le... -

Un groupe de dignitai

Un groupe de dignitai

res visitant le...

-

Verre à tige, bouteil

Verre à tige, bouteil

le à vin, coque... -

Vue du château Haldim

Vue du château Haldim

and et de la Pl... -

Vue du château Saint

Vue du château Saint

- Louis, sur la... -

Vue générale des foui

Vue générale des foui

lles au château...