Royal College La Flèche, Wellspring of Missionary Zeal

par Haudrère, Philippe

A number of key figures from the early days of New France and Acadia either studied or taught at the Jesuit college in La Flèche. Notable figures include François Montmorency de Laval, first bishop of New France; Jérôme Le Royer de la Dauversière, the visionary behind the founding of Montreal; and several Jesuit missionaries, among them Canadian martyrs Isaac Jogues and Gabriel Lalemant. In the 18th and 19th centuries, the college, whichis located in the former French province of Anjou, set itself clearly apart from the other institutions training missionaries bound for America, thereby playing a key role in the missionary history of New France and Acadia and inthe creation of the Canadian Catholic Church.

Article disponible en français : Collège royal de La Flèche, l'esprit missionnaire et le Canada

The College and its Architecture

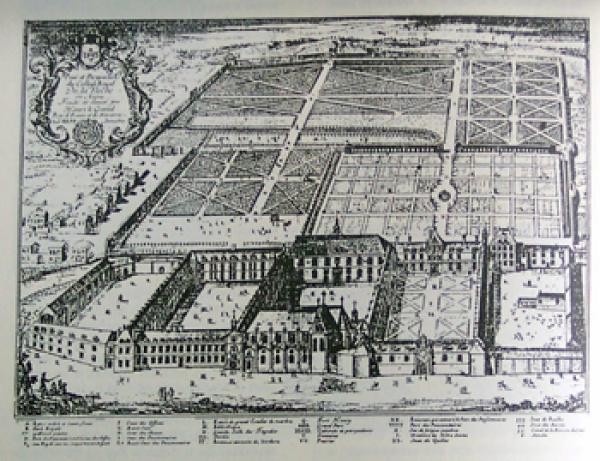

For modern-day travellers making their way towards the village of La Flèche, the old Jesuit college is hard to ignore. Located just 50 km [31 miles] north of Loire, between the cities ofAngers and Le Mans, college campus is a massive structure surrounded by low houses that by contrast dominates the center of town. From the sheer size ofthe buildings to the sharp angles of the roofs that support the chapel's belfries, it is easy to imagine that such an edifice must have caused quite a stir when it was built in the early 17th century, especially in a town of 4,000 people. While on an administrative inspection tour of the province in 1664, Charles Colbert, younger brother of Louis the 14th's famous finance minister, observed that "if there is one noteworthy thing in this town, it would have to be the stunning Jesuit college. What's more, all of the businesses and workshops in town combined are less lucrative and proud than the school and its students." (NOTE 1)

A late-17th-century engraving by Franz Ertinger (NOTE 2) depicts the layout of the college, with its various buildings grouped around three large courtyards. To the west, centred aroundthe "Cour des Pères" [Fathers' Courtyard"], were the quarters of the priests who ran the school. In the centre, next to the chapel, was the "Cour des Classes" [Classroom Courtyard], where students and teachers worked and prayed. To the east was the "Cour des Pensionnaires" [Boarders' Courtyard], surrounded by refectories and dormitories. At each end of the building, service buildings such as kitchens, linen rooms, tack rooms, stables, butchers' shopsand servants' quarters were flanked by smaller courtyards. The complex has remained essentially unchanged since the 17th century, except that it has been used as a military academy since the Jesuits left in 1762, its conservation and upkeep now ensured by the French government. The college's chapel is considered a historic monument, and the centre of La Flèche, the oldest part of town surrounding the college, is a heritage conservation district.

A Call for Missionaries to North America at La Flèche

A unique characteristic of the college's history in the 17th and 18th centuries is the number of students who would become missionaries in Canada. Of the 254 Jesuit missionaries sent to North America between 1610 and 1760, more than 60 - a quarter of the total - were once students at La Flèche (a complete list can be found at the end of this document). This figure is even more surprising given that La Flèche was not the only educational institution in France to be run by the Society of Jesus (the Jesuits); there were 46 such establishments in 1616, 74 in 1717 and 88 in 1749. The Superior General of the Society of Jesus in Rome expressed his satisfaction with the number of missionary vocations taken up at La Flèche in a letter to the rector of the college in 1635. He writes: "You mentioned in your letter that the college was bursting with missionary zeal for Canada. I have no doubt that the example set by those who preferred Canada's ruggedness and forests to the familiar skies of their homeland may have inspired others to seek out the same heavenly crown and, despite the distance, to compete with the others in the pursuit of the highest of virtues." (NOTE 3) It is important to remember that for Ignace de Loyola, the Society's founder, missionary work was a top priority. But what was the reason his wishes were carried out so faithfully at La Flèche?

Jesuit colleges were home to priests having made solemn vows. These men were responsible for teaching the faithful, providing spiritual leadership and managing the colleges. However, the younger Jesuits, who were fresh out of novitiate training and not yet ordained, having made so-called "simple vows," also completed their philosophical and theological studies at these same colleges under the direction of the older priests. These younger brothers were responsible for supervising and providing students with moral and religious guidance. Most of the missionaries were part of this group of younger Jesuits, who left for Canada after completing their intellectual and religious education-a sign of their youthful exuberance.

The Creation of Royal College La Flèche

The missionary spirit at LaFlèche can also be explained in part by some of the unique circumstances surrounding its founding. In fact, the college was founded by royal decree. In 1603, King Henry IV gave his castle in La Flèche to the Society of Jesus for the creation of an educational institution. The decision marked the Jesuits' return to France, for the order had been banished in 1594 by Parliament (that is to say a high court) after Henry III was assassinated by Jean Châtel, a former student with the Jesuits. With the founding of the school, the "very Christian" king, who had just renounced Protestantism, announced his attachment to Roman Catholicism and its most active participants, the Jesuits. Furthermore, Henry IV allotted significant financial resources to the school, namely an allowance of 20,000 livres tournois, to be collected from a number of abbey sthroughout the region. The allowance made it possible for the school to comfortably take on between 1,200 and 1,400 students and provide foreign students with free admission. The education provided by the College was of the highest quality, incompliance with Roman Catholic orthodoxy and capable of competing with the region's biggest Protestant school, the Calvinist academy located sixty kilometres to the south in Samur, just across the Loire River.

At the same time, the intellectual vitality of the priests at the college was exceptional. In his Discourseon the Method, philosopher René Descartes, who studied at La Flèche from 1604 to 1612, attests to the quality of teaching at the college, saying "I was in one of the most famous schools in Europe." (NOTE 4) In 1683, replying to a correspondent looking for advice on his son's education, Descartes writes that "while I do not believe that all things which are taught in philosophy are as true as the Gospel, I feel that, because it is the key to the other sciences, it is very useful to have studied it thoroughly - in the way it is taught in Jesuit schools. [...] And here I must pay homage to my masters, for nowhere is philosophy taught better than at La Flèche [...]." (NOTE 5)

Latin Odes, a Testimony to the Era's Missionary Zeal

Can the missionary zeal that permeated the College be characterised? A collection of Latin odes complied and published by Father Chevalier provides some insight. Some of the odes, which were sung by students on special occasions - on the departure of a missionary, for example-are particularly descriptive. Such is the case of ode 5, "To celebrate the Jesuit fathers sent to the shores of Canada, their heroic and unflinching courage and their ardent desire to work for the glory of God," ode 6, "For these same fathers, whose hearts burn with compassion for the salvation of the Canadian people" and ode 8, "For Nicolas Adam, to wish him Godspeed upon departing on his voyage to Canada." These three odes all consistently follow the model set by Saint Francis Xavier, companion to Saint Ignace and missionary to the East Indies. They make frequent use of military vocabulary, extolling the virtues of combat with allusions to the physical obstacles encountered in the cold climate of the wilderness amongst peoples decimated by hardship and starvation, as well as to the steadfast optimism of the missionaries whose hearts burned with the zeal to spread the knowledge of the Kingdom of God. The following passage is an eloquent tribute to the missionary zeal that was held in such high regard at La Flèche:

The powerful army of Ignace's sons is marching...

Be brave, sons of Loyola! Tireless family,

Worthy heirs to the courage of the ancestors,

Fearless, with the strength and fire of youth,

You send forth your phalanxes on foreign soil,

Disciples of Ignace, burned by the cold,

Run towards the Boreal lands,

All white with snow.

And soon that snow will disappear,

With the return of joyful spring

The earth will don its golden finery

Rediscover its endless fertility

Beneath a sky of fire. (NOTE 6)

The themes evoked in the above passage resemble those found in letters written by great Canadian martyrs like Father Isaac Jogues, who studied philosophy at La Flèche for three years before coming to Canada. Jogues, who was known for the quality of his writing, worked among the Huron and Iroquois before being killed in 1646 by an axe blow to the head.

One could still wonder what it is that drove the young priests trained at La Flèche to choose Canada over China or the Indies, where there were other Jesuit missions.

Enemond Massé's Devotion to Canada

The answer undoubtedly lies in the far-reaching influence of Father Enemond Massé. Born in Lyon in 1575, Massé entered the novitiate program in 1595 and requested to be sent as a missionary immediately following his ordination. He arrived in Acadia in 1611, where he was taken prisoner by the English two years later. The English sent him back to France and he served as the rector of La Flèche College for more than ten years. In 1625, he returned to Quebec, this time to convert the Montagnais. There, on the shores of the St. Lawrence, he met Charles Lalemant, François Ragueneau and Anne (NOTE 7) de Noue, young priests who had studied at the College. Massé was once again taken prisoner by the English in 1629 and he returned to Europe, where he spent three years in charge of a group of students at La Flèche, accompanied by a number of his colleagues from New France. In 1633, he returned to Quebec with Father Jacques Buteux, who had just completed his theology studies at the College. Enemond Massé died in Sillery, near Quebec City, in 1646. Following his death, the movement was kept alive through the writings of priests staying at the College who had returned from Canada and through regular readings of the Lettres Édifiantes, or Relations des Jésuites.

Notable Jesuits Who Studied at La Flèche

The priests at La Flèche spread missionary ideology among their students, who, as adults, often held important positions in French society and in many cases kept Jesuit confessors who encouraged them to found missions. The most important example of this in New France is that of Jérôme Le Royer de la Dauversière, who founded the Société de Notre-Dame de Montréal, an organisation that played a key role in the creation of Ville-Marie (Montreal). François Montmorency de Laval, the first bishop of New France, stayed at the College from 1631 to 1641 and made no bones about the profound influence those years of study had on him. In August 1659, two years after arriving in New France, he wrote to the Superior General of the Society of Jesus in Rome, saying: "Only God, who probes deep into the hearts of men and reaches into the depths of my soul, knows how much I owe to your Society, which welcomed me in its bosom as a child, which fed me its precious doctrine as a young man and which has never stopped giving me strength and encouragement. While so much past kindness has brought me close to your Society, new ties continue to strengthen this loving relationship. It has come to me, Reverend Father, to share in the work of your children in this mission in Canada, this vine which they have watered with their sweat and even their blood. I have seen and admired the work of your Fathers; not only have they succeeded among the neophytes [novices], but also among the French, in whom their example and the sanctity of their lives have inspired such expressions of piety that I am not afraid to proclaim that these men exude the very essence of Christ wherever they work. May your Fatherhood continue in its affection; by blessing us with it, it will find nothing in me that is not of the Society. For I feel it; there is nothing me that I do not owe, that I do not give, to the Society." (NOTE 8) When one understands the strength of the ties between Mgr. de Laval and Canadian Jesuits throughout his entire episcopate, it is impossible to question the important role La Flèche College played in the founding of the Canadian Catholic Church.

Today, the College is one of France's most celebrated military academies. Declared a Prytanée Militaire by Napoléon I in 1808, the school has trained several generations of general officers. This reputation for military excellence, already long and storied itself, has erased the memory of the missionary spirit that reigned in the days of the Jesuits.

Philippe Haudrère

Université d'Angers, France

NOTES

Note 1: Anjou Archives, collection of previously unpublished documents and memoirs on the province, published by Paul Marchegay, Angers, 1843, t. 1, p. 178.

Note 2: B.N.F. Estampes, SNR-3 Ertinger (F.).

Note 3: Monumenta Novae Franciae, t. 3. - Fondation de la mission huronne, 1635-1637, ed. L. Campeau, Rome-Quebec, 1987; excerpt from doc. 6, p. 9-10, P. Mutius Vitelleschi to P. Claude Noiriel, Rome, March 10th, 1635, and doc. 15, p. 15-16, from the same to the same, Rome, June 20th, 1635 (trans. from the Latin). The complete quote [French only] is attached at the end of the document.

Note 4: Œuvres de Descartes, Paris, ed. Charles Adam and Paul Tannery, 1985, t. 6, p. 5.

Note 5: Id., t. 2, p. 377-379. Alonger excerpt [French only] is attached at the end of the document.

Note 6: Ioannis Chevalier, Burgundi, Polliniensis, e societate iesu, Polyhmnia, sive variorum carminum [...], cum scholis gratiam studiosae juventutis, Flexiae, 1647. [Jean Chevalier,Bourguignon, of Pollionay, of the Society of Jesus, Polyhymnia ... with the help of the school's studious pupils. La Flèche]. Extraits. A longer passage of ode 6 [French only] is attached at the end of the document.

Note 7: In 17th-centuryFrance, this name was used for both men and women.

Note 8: Quebec, August 1659, Archives du Séminaire de Québec, document translated from the Latin, graciously provided by Mr. Martin Fournier.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Campeau, Lucien (ed.), MonumentaNovae Franciae, 1. La première mission d'Acadie(1602-1616, 2. Etablissementà Québec (1616-1634), 3. Fondation de la mission huronne (1635-1637,4. Les grandes épreuves (1638-1640), 5. La bonne nouvelle reçue(1641-1643), 6. Recherche de la paix (1644-1646), 7. Letémoignage du sang (1647-1650), 8. Au bord de la ruine (1647-1650),9. Pour le salut des Hurons (1657-1661), Monumenta Historica SocietatisJesu, Rome - Quebec, and Montreal, 1967-2003

Le Bœuf, François, La Flèche, Le Prytanée, Sarthe : Inventaire général des monuments et des richessesartistiques de la France : Région des Pays de la Loire, Nantes, 1995.

Lécrivain, Philippe, Lesmissions jésuites : pour une plus grande gloire de Dieu, Paris, 2005.

Rochemonteix, Camille de, Un collège de jésuites aux XVIIe et XVIIIe siècles : le collège Henri IV de La Flèche, 4 vol., Le Mans, 1889.

Thwaites, Ruben Gold (ed.), The Jesuit Relations and Allied Documents, 73 vol., Cleveland, 1896-1901.

Additional DocumentsSome documents require an additional plugin to be consulted

Images

-

-

Costume de Jésuite du

XVIIe siècle. ... -

Gabriel Lalemant (161

Gabriel Lalemant (161

0-1649) -

Le Rd. P. Isaac Jogue

Le Rd. P. Isaac Jogue

s de la Comp[ag...

-

Monseigneur François

de Montmorency ... -

Monument Ennemond Mas

Monument Ennemond Mas

sé -

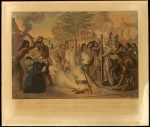

Mort héroïque de quel

Mort héroïque de quel

ques pères de l... -

Père Paul le Jeune. P

Père Paul le Jeune. P

hotographie d'u...

Documents PDF

-

Liste des missionnaires jésuites du Canada passés par La Flèche, 1610-1760

Liste des missionnaires jésuites du Canada passés par La Flèche, 1610-1760

-

Extrait de Jean Chevalier, Bourguignon, de Pollionay, de la société de Jésus, Polymnie...

Extrait de Jean Chevalier, Bourguignon, de Pollionay, de la société de Jésus, Polymnie...

-

Extrait de Monumenta Novae Franciae, t. 3. –

Extrait de Monumenta Novae Franciae, t. 3. –

-

Extrait de Œuvres de Descartes

Extrait de Œuvres de Descartes

-

Lettre que Mgr de Laval écrivait au Général des Jésuites à Rome quelques semaines après son arrivée en Nouvelle-France, en 1659

Lettre que Mgr de Laval écrivait au Général des Jésuites à Rome quelques semaines après son arrivée en Nouvelle-France, en 1659