Quebec Beer, Brewers and Breweries

par Ferland, Catherine

Beer is the most popular alcoholic beverage in Canada and Quebec. Beer drinking as a tradition dates back to the days of New France, making brewing one of the oldest trades practiced in the Lawrence Valley. However, both brewing practices and the popularity of beer underwent significant changes, as the British tradition began to have a strong influence on the beer industry through the establishment of the first large-scale modern-day brewery, the Molson Brewing Company. The Industrial Revolution made it possible for beer to become a mass-produced commodity, brewed and bottled in factories and distributed by increasingly sophisticated infrastructures. Nowadays, microbreweries have revived the practices of artisanal brewing, as a number of festivals celebrate the many varieties of this ancient beverage.

Article disponible en français : Bières, brasseurs et brasseries au Québec

The Contemporary Brewing Industry

Canadians drink a lot of beer. In 2008, average beer consumption was 77.2 litres per Canadian over the age of 15, making beer the most popular alcoholic beverage in the country in terms of both volume and monetary value. (NOTE 1) While the market share held by imported beers is growing, 4.5 out of every 5 beers consumed in Canada in 2007-2008 was brewed domestically. That figure includes all beers--ales, lagers, blondes, ambers, reds, browns, etc.--produced both industrially and in microbreweries. (NOTE 2) In Quebec, beer is not the product of a single tradition, but rather comes from a mixed background. In any case, be it urban or rural, quaint or trendy, beer is a part of our cultural identity-and as the saying goes: you are what you drink!

A Centuries-Old Recipe

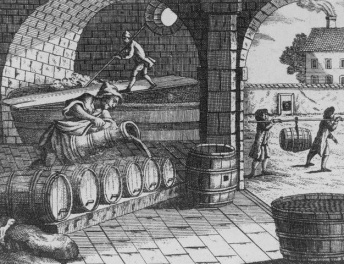

Beer is a universal beverage, quite possibly the earliest man-made drink. It was long an artisanal beverage, produced and consumed by individuals. It wasn't until the 10th century that European cities became populous enough to support actual brewers and breweries. Despite its age, the basic recipe for beer has remained surprisingly constant throughout the centuries. While the brewing process relies on steps that have remained fundamentally unchanged (malting, brewing and fermentation) (NOTE 3), a number of innovations have nonetheless improved the quality of the beer produced and extended its shelf life. One of these innovations was the use of hops, which became common practice in the 15th century. However, it is the Industrial Revolution that gave rise to a number of technological innovations that have remained important to this day, such as the development of pressurized filtration and racking techniques, bottling technology, refrigeration, etc. The research carried out by Louis Pasteur also led to a better understanding of the fermentation process, as well as a substantial improvement in the sanitary conditions inside breweries.

Beer Under the French Regime

As a result of various colonisation efforts, beer and beer making soon crossed the Atlantic to the New World. The popular drink was found among English settlers in Virginia as early as 1587 and, a few decades later, it was being consumed a little farther north by colonists in small French settlements along the St. Lawrence. The first brewers in New France were the Recollects, followed by the Jesuits, who founded breweries in the early 17th century. In 1668, Intendant Jean Talon [French colonial administrator of New France] tried to persuade the colonists to forgo expensive wine and spirits imported from France in favour of locally-produced beers. Alas, Talon's call fell on deaf ears and his brewery closed seven years after opening. Apparently, Canadians don't appreciate being told what to drink! In New France, beer, cider, wine, spirits and rum were the most common alcoholic beverages on colonists' tables. Nonetheless, several dozen breweries in Quebec City, Trois-Rivières and Montreal produced beer, which became especially popular when war made European beverages hard to come by.

Molson and the British Influence

The real boom in the Canadian brewing industry came when the colony was surrendered to England at the end of the Seven Years War [for the Americans it is known as the French and Indian War] (1756-1763). The arrival of British soldiers and businessmen in Quebec City and Montreal gave rise to many new breweries, whose beer-drinking clientele increased exponentially following the American Revolution (1774-1776), when nearly 10,000 Loyalists came to the Province of Quebec. French brewers not only adapted to the new socioeconomic realities by expanding their client base, but also took full advantage of the English brewers' technological innovations and know-how.

John Molson's contributions to the Quebec brewing industry cannot be ignored. Born in England in 1763, Molson founded his Montreal brewery in 1786. He was also involved in (among other things) the construction of steamships and railroads, thereby helping to open up new markets for Canadian products. Molson also took an interest in the socioeconomic and cultural growth of his new hometown. In the 1820s, he played a part in founding the Montreal General Hospital and the Theatre Royal, the city's first permanent theatre. (NOTE 4)

However, John Molson's most important contributions were to the production-and especially the commercialisation-of beer. Important advances made by the company include the first glass bottles in 1844, direct retail sales and pint bottles in 1859 and the use of electric rather than steam-powered machinery in the early 20th century. The company was also at the forefront of refrigeration technology and also pioneered new labelling, packaging and shipping techniques. In the 1910s, while producing more than 2 million gallons of beer each year, the Molson brewery acquired new automatic bottling equipment and motorised delivery vehicles. The company was also an innovator at a social level, hiring women in its bottling plants as early as the 1870s!

Despite Molson's importance, one cannot forget the many other brewing companies that shared the Canadian market, a number of which were established in the 19th century. Alexander Keith founded a brewery in Nova Scotia in 1829. Seven years later, John H. Sleeman founded his own brewery in St. David, Quebec. Thomas Carling founded his Brewing and Malting Company in London, Ontario in 1840. Meanwhile, both the Boswell and McCallum's breweries were experiencing their glory days in Quebec. It was however the Labatt Brewing Company that emerged as Molson's biggest competitor. Founded by John Kinder Labatt in London, Ontario in 1847, the company opened a branch office in Montreal in 1878 to facilitate the distribution of its products in Quebec. (NOTE 5) At this point, it is quite obvious that the Canadian brewing industry was almost completely run by Englishmen.

The Rise of the Monopolies

In the early 20th century, it became very difficult for small Quebec breweries to compete with the industry's big names. During World War I, the price of basic ingredients rose to the point that several breweries were forced to either merge with or sell out to the competition. Others simply folded. The consolidation of the industry made it possible for the remaining breweries to be more competitive and face future challenges.

Surprisingly, beer fared rather well during the Prohibition. Temperance legislation was first passed in Saskatchewan in 1915, before the movement spread to the other provinces. Under Prohibition, the production, distribution and sale of alcoholic beverages was strictly forbidden. However, some breweries managed to come out on top despite the difficult situation. Among them was Labatt, whose success was due to two tactics: first, the company produced "regular" beer to be exported illegally into the U.S.; and second, it brewed "temperance beer" (less than 2% alcohol per volume) for sale in Ontario. (NOTE 6) Sleeman, Molson and Carling all used similar tactics, thereby cementing their position and lining their coffers. Interestingly enough, during a referendum held in Quebec in 1919, the public voted to exclude beer, wine and cider from the prohibition law. With this decision, Quebec became the only place in Canada or the U.S. where Prohibition was not absolute, thereby allowing Quebec breweries to return to business as usual. The Great Depression and World War II (1939-1945) further narrowed the industry to a few key players.

The years that followed thus belonged to the monopolies, whose market share continued to grow thanks to the development of advertising and the rapid growth of mass media (radio and especially television). The women's rights movement of the fifties and sixties opened up new horizons for the industry, which attempted to attract a new female clientele by creating so-called "light" beers.

The Birth of the Microbreweries

Prior to the late 1970s, the beer market in Quebec was almost exclusively dominated by North American brewing giants Molson, Labatt and O'Keefe. (NOTE 7) However, the decade that followed saw a rise in the popularity of beer produced in microbreweries. While some consumers remained faithful to the beer produced by the big breweries, a certain slice of beer-drinkers demanded more robust flavours and less conventional concoctions. Thus, a number of microbreweries sprung up over the years, including La Brasserie Massawippi (1986), Le Cheval Blanc (1987), Les Brasseurs du Nord (1987), Les Brasseurs GMT (1987), McAuslan (1989), Unibroue (1991), the Schoune farm and brewery (1994), La Brasserie Seigneuriale (1994) and La Barberie (1997), to name but a few. (NOTE 8) Some were locally successful, but never managed to firmly establish themselves in the market and thus were forced to close or were sold, while others managed to break into the market by presenting their beers at major beer tasting events and contests.

While many Western countries have an interest in artisan beer, it is important to note that the phenomenon is slightly different in Quebec. Following the example of many so-called produits du terroir [a term used to describe goods produced locally and--ostensibly--according to traditional values], many of these beers are far from being products of a newly-rediscovered tradition, but are rather innovative products cleverly marketed to lend them an aura of authenticity. As such, artisan beer in La Belle Province [Quebec] is a new cultural phenomenon; for whereas countries such as Germany, Belgium and England are returning to their roots and revisiting traditional brewing techniques, microbreweries in Quebec are experimenting with new ways of making beer. (NOTE 9) Currently, we are witnessing the amalgamation of traditional artisan techniques and methods with cutting-edge scientific knowledge-it is truly a mixture of centuries-old ingredients and bold innovation!

Quebec microbreweries, which typically operate with about twenty employees, produce an average of 15,000 to 30,000 hectolitres of beer each year, or less than 3% of the total market. However, these microbreweries do not target the same clientele as the industrial breweries; these are special, unique products aimed at "connoisseurs." They sometimes contain unconventional ingredients and locally-produced hops and grain, making them 100% Quebec products. As beer becomes a gastronomic delight on par with wine, it is becoming more and more common to see organised beer tastings and published guides for pairing types of beers with specific cheeses and culinary dishes. (NOTE 10)

Becoming a Brewer Today

There are several ways of learning to become a brewer. For centuries, the only way to learn most trades, including brewing, was to become an apprentice, and even today it is possible to learn the trade "on the spot," either through self-training or by completing an apprenticeship (ranging in length from several weeks to several months) with an established brewery. "I started out making a regular mess of my mother's kitchen, as I was learning to make beer," says Sébastien Déry of Bières de la Nouvelle-France. "That's how most brewers in Quebec got started." (NOTE 11) There are, however, programs to learn the trade, since certification is required to obtain a licence for a brewery/restaurant or microbrewery from the Régie des Alcools du Québec [Liquor Board].

In Europe, notably in France, Germany, England and Belgium, where the brewing tradition is much older, there are higher-learning programs devoted to trade. (NOTE 12). In Quebec, Saint-Hyacinthe's Laboratoires Maska have been giving brewing courses since 1996. A number of different courses are offered: an advanced brewing course (five days), a course on the basics of brewing (five days) and finally another on working with yeast (two days). The Laboratoires also help students found their own brewery. With campuses in Chicago, Munich and Montreal, the Siebel Institute of Technology also provides educational programs in brewing science and technology (including a Master Brewer program). The Institute gives courses in subjects ranging from home brewing to the microbiology of the industry's most advanced breweries. A partner with Germany's Doemens Academy, the Siebel Institute's programs are recognized by the World Brewing Academy (WBA) and students who complete their studies there earn the WBA International Diploma in Brewing Technology. As a side note, this intensive, twelve-week program is also offered in the form of correspondence course training.

Depending on the school and its particular teaching methods, aspiring brewers not only learn about cooking, brewing and filtration techniques and the different varieties of grains and hops, but also about enzymes, microorganisms, heat exchange and processing, the biochemistry of barley, starches, bitter substances, pH and the reactivity of water ions, etc. – it is quite the program!

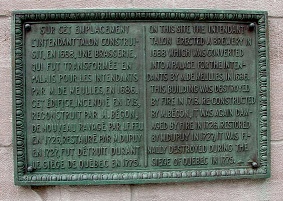

Spreading the Word and Celebrating Beer

Even though beer is an important element of our cultural history, there is only one econo-museum devoted to it in all of French Canada. The museum, which is run by the Les Bières de la Nouvelle-France microbrewery in Saint-Alexis-des-Monts, Quebec, features interpretive panels and brewery artefacts that teach visitors about beer's origins and the various steps that go into making it. Quebec City's urban heritage society (SPUQ) offers a tour known as La Route de la Bière [The Beer Route], along which guests can explore the Îlot des Palais and wander the streets of Old Quebec City, an area that was once home to a number of breweries. (NOTE 13) The Îlot des Palais itself is rich in heritage. Intendant Talon's brewery was built there, as were the Dow and Boswell breweries. As a result, the site contains artefacts dating back to both the French regime and the Industrial Revolution, making it one of Quebec's most important brewing heritage landmarks.

A number of events and festivals held throughout the province from late summer until fall celebrate beer and the work of brewers. Montreal's Mondial de la Bière, founded in 1994, welcomes thousands of visitors every year. The Fête Bières et Saveurs (Chambly), the Oktoberfest des Québécois (Mascouche) and the Festival des Bières du Monde (Chicoutimi) all give visitors the chance to discover the hoppy beverage. At a number of other events, such as the Fêtes Gourmandes de Lanaudière [Epicurian Festival] and the Festival de la Gastronomie de Québec, beer may not be the focus, but it is still given special attention. Finally, one must not forget the Journée Québécoise de la Bière, [Quebec Beer Day] the first edition of which was held on August 15th, 2009. With the participation of several dozen breweries, restaurants and bars across Quebec, the day is a celebration of the regional qualities of the breweries, as well as beer's place in Quebec's heritage. (NOTE 14)

The world's oldest fermented beverage is also one of its most versatile, able to adapt to new realities. Look no further than the abundance of beer-related websites for proof that beer's place in the 21st century is assured. With such widespread appreciation for the product of their work, it doesn't look like the brewer's trade will fade into oblivion any time soon.

Catherine Ferland, Ph.D.

Associated Professor, History Department, Université de Sherbrooke

Assistant coordinator, Encyclopedia of French Cultural Heritage in North America

NOTES

Note 1. These figures are high when compared to beer consumption in France (41 litres/person/year), but lower than consumption in other countries with rich brewing heritages, such as Germany (143 L), Belgium (121 L) or Great-Britain (110 L). Statistics Canada, http://www.statcan.gc.ca/ads-annonces/23f0001x/hl-fs-fra.htm#a8, page visited October 28th, 2009.

Note 2. Statistics Canada, http://www.statcan.gc.ca/daily-quotidien/090420/dq090420b-fra.htm, page visited October 28th, 2009. One of the largest groups is the Brewers Association of Canada, which produces more than 98% of the Canadian beer sold in the country. In the early 2000s, their contribution to Canada's economy averaged almost 14 billion dollars per year. In fact, the brewing industry accounts for 12% of the GDP produced by the food sector in Canada. See the Brewers Association website: http://www.brewers.ca/default_e.asp?id=3

Note 3. Malting involves letting grains germinate in water then drying and roasting them to varying degrees of darkness. This operation, known as kilning, is what determines the beer's final colour. Technically speaking, brewing consists of cooking the malt in a vat with water. The resulting brew is generally filtered and flavoured. The wort is then transferred into a cool vat to rest, and yeast is sometimes added. There fermentation begins: sugars become alcohol, and the wort becomes beer.

Note 4. http://www.molson.com/CompanyInfo.aspx John Molson's descendents had close ties with the world of sports, especially with hockey. See: Gilles Laporte, Molson et le Québec, Montréal, Michel Brûlé, 2009. Molson continues to exert a powerful influence on Canadian society, especially in Quebec.

Note 5. http://www.molson.com/en/MolsonHeritage/MolsonHistory/JohnMolsonBio.aspx

Note 6. http://www.labatt.com/french/lbc_company/lbc_history_2.htm

Note 7. Mario D'Eer, Le Guide de la bière, Montréal, Éditions du Trécarré, 2004, p. 30.

Note 8. An up-to-date list of Quebec microbreweries can be found at http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/List_of_Quebec_microbreweries. See also: Sylvain Daigneault, Histoire de la bière au Québec, Montréal, Broquet, 2006, p. 77-100.

Note 9. Mario D'Eer, Ales, lagers, lambics : la bière, Montréal, Éditions BièreMag / Trécarré, 1998, p. 47.

Note 10. See, for example: Mario d'Eer, Épousailles bières et fromages, Guide d'accords et de dégustation, Montréal, Éditions du Trécarré, 2000, 255 pages.

Note 11. Karine Parenteau, "La bière, c'est sérieux!," Voir, August 18, 2005 [electronic resource available online [French only] at http://www.voir.ca/publishing/article.aspx?zone=1§ion=11&article=37587. Page visited January 12th, 2010.

Note 12. For example, the department of biotechnology of the university of La Rochelle offers a degree in "brewery operation." The French Institute of Brewing and Malting (IFBM) (www.ifbm.fr) and the École Nationale Supérieure d'Agronomie et des Industries Alimentaires (www.ensaia.inpl-nancy.fr), both of which are located in Nancy, also offer a number of training programs. Courses leading to a degree in brewing are also offered at the University of Louvain-La-Neuve, Belgium. In the U.S., the Master Brewers Association of the Americas (http://www.mbaa.com/), founded in 1887, aims to promote the trade of brewer while improving the knowledge, methods and techniques of brewery workers.

Note 13. http://www.houblon.net/spip.php?article6300

Note 14. The Mondial de la Bière publishes Beer Trek travel guides for Manitoba, Ontario, Saskatchewan and Quebec (6th edition, 2009). The guides list festivals, breweries and vendors specialising in beer. (http://www.routebiere-beertrek.com/) It is also possible to search for breweries by region or by type on the Bières du Québec website.

BIBIOGRAPHY

Daignault Sylvain, Histoire de la bière au Québec, Montréal, Broquet, 2006, 184 pages.

Ferland Catherine, Bacchus en Canada. Boissons, buveurs et ivresses en Nouvelle-France, Québec, Septentrion, 2010, 432 pages.

Ferland Catherine, "De la bière et des hommes. Culture matérielle et aspects socioculturels de la brasserie au Canada, XVIIe-XVIIIe siècles," Terrains & travaux, Cahiers du département de sciences sociales de l'ENS de Cachan [France], no. 9 (2005), p. 32-50.

Laporte Gilles, Molson et le Québec, Montréal, Michel Brûlé, 2009, 150 pages.

Tremblay Mathieu, "Du territoire au boire : la bière artisanale au Québec," History thesis, Université Laval, 2008 [online] http://www.theses.ulaval.ca/2008/25300/25300.pdf

Additional DocumentsSome documents require an additional plugin to be consulted

Images

-

Bouteille de bière «E

Bouteille de bière «E

au bénite» (Qué... -

Brasserie ancienne

Brasserie ancienne

-

Brasserie Boswell, Qu

Brasserie Boswell, Qu

ébec, QC, copie... -

Caisse de bière et la

Caisse de bière et la

vabo, série «La...

-

Chaîne de production

Chaîne de production

, brasserie Daw... -

Chariot à bière de

Chariot à bière de

la Brasserie Mo... -

Chope à bière, vers

Chope à bière, vers

1728-1729 -

Détail du vitrail déd

Détail du vitrail déd

ié à saint Arno...

-

Homme au journal, 27

Homme au journal, 27

octobre 1973, d... -

La compagnie de brass

erie de Beaupor... -

Labatt's London Ale

Labatt's London Ale

-

Les Deux Fils, de la

Les Deux Fils, de la

série «La Taver...

-

Plaque commémorative

Plaque commémorative

apposée à l'îlo... -

Portrait de John Mols

Portrait de John Mols

on (1763-1836) -

Publicité imprimée de

Publicité imprimée de

Molson (en ang... -

Table et verres de bi

Table et verres de bi

ère, série «La ...

-

Trois gars discutant,

Trois gars discutant,

série «La Tave... -

Unibroue - La fin du

Unibroue - La fin du

monde, 2007 -

Vieux monsieur, série

Vieux monsieur, série

«La Taverne» (... -

Voiture de livraison

Voiture de livraison

de Molson, vers...

Vidéos

Documents sonores

-

D’la bière au ciel

Interpreter : Jim Corcoran.

Writer : Jim Corcoran.

Album : Portraits, 1995.

D’la bière au ciel

Interpreter : Jim Corcoran.

Writer : Jim Corcoran.

Album : Portraits, 1995.

-

Deux autres bières

Interpreter : Offenbach.

Writer : Pierre Huet, John McGale.

Album : Les 20 plus grands succès, 1978.

Deux autres bières

Interpreter : Offenbach.

Writer : Pierre Huet, John McGale.

Album : Les 20 plus grands succès, 1978.

Hyperliens

- Festibières du Québec

- Mondial de la Bière à Montréal

- Science infuse – La bière pédagogique (Université de La Rochelle)

- Site du Siebel Institute of Technology (campus de Montréal)

- Bières du Québec (répertoire et réseau social des bières québécoises)