True Portrait of Marguerite Bourgeoys

par Martel, Stéphan

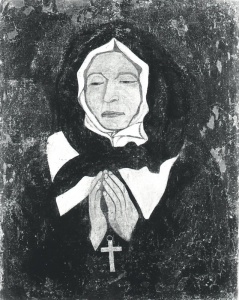

The post-mortem portrait of Marguerite Bourgeoys is the only surviving contemporary depiction of one of the most remarkable figures in the history of Montreal during the 17th century. Painted in 1700 by Pierre Le Ber, the work has been in the hands of the Congregation of Notre-Dame ever since and is currently exhibited at the Marguerite Bourgeoys Museum. During the 19th and early 20th centuries, the portrait was retouched several times, completely altering its appearance. The restoration of the painting in 1963-1964 revealed the true face of Marguerite Bourgeoys and the authentic work of one of Canada's earliest painters.

Article disponible en français : Vrai portrait de Marguerite Bourgeoys

The Original Work of the Artist Pierre Le Ber

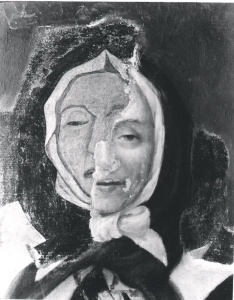

This post-mortem portrait(NOTE 1) of Marguerite Bourgeoys was painted immediately after her death in January of 1700 by French-Canadian artist Pierre Le Ber. The 49.5 cm [19.5 inches] by 62.3 cm [24.9 inches] oil on canvas is a bust portrait of an elderly woman set against a brownish background with her eyes half-closed and her hands joined in prayer. The style of the work is simple, primitive and a bit stiff. Since 1998, this significant piece of French North American artistic and religious heritage has been on display at the Marguerite Bourgeoys Museum in Montréal.

Born into a wealthy family, Pierre Le Ber was the son of Montréal merchant Jacques Le Ber and Jeanne Le Moyne. His sister was the famed recluse, Jeanne Le Ber. He was born in Ville-Marie (Montreal) in August 1669 and died on October 1st, 1707, at the age of 38. Nothing is known about his artistic training. Unlike his father, he showed little interest in business(NOTE 2) and devoted most of his time to his passion of painting. Le Ber was a generous benefactor of Montreal's religious communities. He helped found Montreal General Hospital with the Charon Brothers and also financed the establishment of artisan workshops at the institution.(NOTE 3) In 1697, he had a small chapel built at his own expense in Pointe-Saint-Charles, which he decorated himself. The posthumous inventory of Le Ber's studio and the rare canvases that have been attributed to him suggest that the artist devoted himself primarily, if not exclusively, to religious themes and portraits.

The Origins of the Portrait

For the Sisters of the Congregation of Notre-Dame, the year 1700 began on a mournful note with the passing of their founder, Marguerite Bourgeoys, who died on January 12th after a short but acute illness. The day of her death, Marguerite Le Moyne, the superior of the Congregation, summoned her cousin Pierre Le Ber to paint a portrait of the deceased. A record of this event has been handed down in an anecdote typical of the hagiographic writings of the day:

"Monsieur Le Ber's son had been called upon to paint a portrait of our dear Mother shortly after her death. After receiving Communion for her in our chapel, he came prepared to work, but he was suddenly stricken with a severe headache and could not begin. One of our sisters gave him a tiny lock of our deceased Mother's hair. He placed it under his wig and at once felt so much better that he began to work with ease; he and those watching him were astounded."(NOTE 4)

Le Ber had to work rapidly to sketch his model because Marguerite Bourgeoys was only on display for one day in the congregation's chapel. The following day (January 13th), her body was moved to Notre-Dame Church for the funeral.(NOTE 5) In the meantime, the Sisters of the Congregation of Notre-Dame had their founder's heart embalmed so they could put it on display for one month in the congregational chapel for viewing by the faithful. On February 12th, 1700, the heart enclosed in its lead box was "placed within the choir wall"(NOTE 6) of the chapel and Le Ber's portrait hung in the niche above.

From this point on, the history of the portrait becomes harder to trace, as mentions grow scarce and rather brief on the specifics. The painting was removed from the chapel some time before 1728 and then restored to its position in 1757.(NOTE 7) It was rescued from the flames that destroyed the building in 1768 and then hung anew in the reconstructed chapel in the following year. In the late 1860s, Monseigneur Bourget, the second bishop of Montreal, ordered that the portrait be permanently removed from its chapel location.(NOTE 8) After this, it was undoubtedly kept at the motherhouse of the Congregation. The work survived another fire that destroyed the Congregation's fifth motherhouse in 1893. The next recorded reference dates from 1908, when the canvas was given a new home in the General Council room at the Congregation's new motherhouse. It was still there five decades later when a number of nuns began to seriously question the authenticity of their founder's portrait.

Initial

Doubts about the Authenticity of the Portrait

By 1961, many members of the community were aware that the portrait had been retouched in the past; indeed, the eldest among them had seen the modifications made early in the 20th century with their own eyes. However, a number of nuns had begun to openly question the portrait's authenticity. As a result, they asked Jean Palardy, a specialist in early Canadian art, to examine the portrait and settle their doubts. His conclusions only deepened their suspicions. "The much-softened features [of Marguerite Bourgeoys] are not characteristic of the 17th century," he declared. "I would be curious to see what lies underneath."(NOTE 9)

The prospect of uncovering the original face of their founder encouraged congregational officials to have the painting restored. Restoration was risky, however, because it involved the partial destruction of what was considered the only contemporary portrait of the order's founder. Out of precaution, the sisters photographed the portrait and commissioned artist Jori Smith Palardy to paint an exact copy.(NOTE 10)

Restoring

the Portrait: A Risky Operation

In 1963, steps to restoring the portrait finally got underway. The Congregation's general superior appointed Sister Mary Eileen Scott to oversee the project. She called in Edward O. Korany, a New York-based specialist from the International Institute for Conservation who came highly recommended. Details of the restoration work were recorded in the correspondence between Korany and Sister Scott.

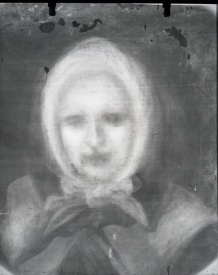

In the course of his analysis, Korany used x-rays to examine the painting. The x-rays revealed the presence of an earlier portrait beneath three coats of white lead(NOTE 11) and various successive layers of paint. Because x-rays cannot penetrate white lead, Korany was unable to assess the condition of the original work of art. Nonetheless, the x-rays did indicate that the face, headdress and hands were completely different than those depicted in the visible portrait. Aware of the risks, but convinced of the historical and heritage significance of the restoration, the general superior of the Congregation of Notre-Dame agreed to go ahead with the project.

Work to uncover the original portrait got underway in September 1963. After two months of painstaking effort,(NOTE 12) Korany successfully uncovered the original image. The portrait turned out to be essentially intact. Only the backdrop was in very poor condition and had to be extensively retouched. The portrait, which had previously been glued to paperboard and affixed to a pressed wood panel, was mounted on canvas in an old American colonial style frame. The restoration was completed in late March 1964.

Korany's analysis of the various added layers of paint revealed that the portrait had undergone two major restorations in the 19th century that had radically altered the earier original work. During the initial restoration carried out during the first half of the century, Marguerite Bourgeoys' physiognomy and hands had been modified. The second major set of alterations had occurred during the latter half of the century. This time, however, the artist had retouched the face and painted a new head covering.

A Religious and Cultural Artefact

The tradition of post-mortem portraits is a very old one dating back to the late 14th century medieval Europe.(NOTE 13) The portraits were first popularized in the Nordic kingdoms of Sweden and Norway in the 16th century, before the custom spread to France in the first quarter of the 17th century. They arrived in New France with the religious communities.

The portrait commission given to Pierre Le Ber was seen to meet an emotional need among the sisters of the Congregation for a tangible reminder of their founder. This is why it was so important for the artist to faithfully render the features of the deceased. But the portrait was also used for "instructional" purposes. For it was used to depict Marguerite Bourgeoys as a model for the other sisters. The preservation of the portrait as an integral part of the Congregation's heritage was thus doubly important.(NOTE 14) Even today, the portrait provides the members of the Congregation with a material and spiritual link to their founder and the origins of their community.

According to historical records, Pierre Le Ber's work was presented to the public on two separate occasions at exhibitions organized by Société des Numismates et Antiquaires de Montréal. The first of these was held in 1887 upon the 25th anniversary of this society of coin collectors and antiquarians, and the second in 1892, for the 250th anniversary of Montreal. It was during this period that the portrait first began to take on its current historical and heritage value. For the exhibition organizers, the work was a genuine and tangible reminder of a woman who had played a central role in the history of Montreal, as the founder of Ville-Marie's first school, a pilgrim's chapel and an un-cloistered community with an educational mission.

In 1963-1964, the restoration of the true portrait painted by Pierre Le Ber some 260 years earlier further enhanced congregational and public awareness of the work's cultural and historic value. The restoration gave historians an opportunity to familiarize themselves with Pierre Le Ber's painting style. As a result, four canvases previously labelled anonymous were attributed with considerable certainty to the artist.(NOTE 15)

The restoration attracted the attention of the media(NOTE 16) and art historians,(NOTE 17) generating a number of requests to see and photograph the work and even to borrow it for exhibition. The painting was presented to the public in 1967 at the Montreal Universal Exhibition (Expo 67) and the Montréal Museum of Fine Arts, and at the National Gallery of Canada in 1974.

A Work

Presented at the Marguerite Bourgeoys Museum

The portrait of Marguerite Bourgeoys is an important piece of French North American heritage. Painted by one of the first French-Canadian artists, the work has been preciously preserved by the Sisters of the Congregation of Notre-Dame, although this did not prevent them from having the portrait retouched in the 19th century to bring their founder's face more in line with the values of the new century. Hidden beneath several layers of additional paint, the true face of Sister Bourgeoys, forgotten for over a century, was revealed anew in 1964, at an a time when Pierre Le Ber's more sober, spiritual depiction could be appreciated once again.(NOTE 18)

Since 1998, the portrait has been on exhibit to the public at the Marguerite Bourgeoys Museum, where an entire room is devoted to its remarkable story. With its design reminiscent of an forum or lecture hall, the room housing the True Portrait of Marguerite Bourgeoys is equally rewarding for all comers whether they be on a spiritual quest(NOTE 19) or just visiting as history buffs.

Stéphan

Martel

Historian, Manager, Document

Centre and Archives

Notre-Dame-de-Bon-Secours Chapel/Marguerite Bourgeoys Museum

NOTES

Note 1: A post-mortem portrait is a work painted immediately after a person's death while the body is on display prior to burial.

Note 2: Nicole Cloutier, Pierre Le Ber, 1669-1707, M.A. (History), Université de Montréal, Montréal, 1973, p.27.

Note 3: Pierre Le Ber took up residence at the Montreal General Hospital in 1694. The Charon Brothers gave him three rooms that he used as his painting studio.

Note 4: Charles de Glandelet, La vie de la sœur Marguerite Bourgeoys, Montréal, Congrégation de Notre-Dame, 1993 [1715], p.148.

Note 5: The body was buried in Notre-Dame Church.

Note 6: Charles de Glandelet, La vie de la sœur Marguerite Bourgeoys..., p.146.

Note 7: This information comes from the Congregation of Notre-Dame inventories entitled Livre des meubles et ustencilles. See Denis Martin, Portraits des héros de la Nouvelle-France. Images d'un culte historique, LaSalle, Hurtubise HMH, 1988, pp. 60-61.

Note 8: "Monseigneur Bourget had us remove the painting, which could not be hung in a chapel until the beatification of Our Reverend Mother." Journal de Mère Sainte-Ursule, [between 1874 and 1897], Archives de la Congrégation de Notre-Dame, 200.100-66, fo2. The Bishop of Montreal was acting in accordance with canonical law, which forbade the veneration of any individual not yet beatified or canonized.

Note 9: Remarks by Jean Palardy as noted by a sister. Marie-Anne Gauthier-Landreville, Présentation du Vrai portrait de la Bienheureuse Marguerite Bourgeoys, [1964], Archives du Musée Marguerite-Bourgeoys, [uncoded], p.2.

Note 10: The copy was completed in January of 1962. Note de M. Jean Palardy relative à la reproduction du portrait de Marguerite Bourgeoys par Jori Smith Palardy (copy), November 25th, 1961-January 23rd, 1962, Archives du Musée Marguerite-Bourgeoys, [uncoded].

Note 11: White lead, also known as ceruse, was a high quality pigment made of lead carbonate (70%) and lead hydroxide (30%). Popular with early painters, especially those working with oils, this extremely dense and opaque pigment was appreciated for its high coverage. For more, see Connaissance de la peinture. Courants, genres & mouvements picturaux, Paris, Larousse, 2001, pp. 59-60; Okhra, Conservatoire des ocres et pigments appliqués, http://www.okhra.com/@fr/74027/article.asp (site visited October 30th, 2009).

Note 12: Korany uncovered an average of only 6 cm2 every two hours.

Note 13: Daoust, Jean-Luc, Le portrait en post mortem immédiat des religieuses au Québec : influences, analyse stylistique et fortune graphique, M.A. (Art History), Université de Montréal, Montréal, 2007, p.33.

Note 14: The remembrance that the sisters of the Congregation had of their founder upon her death at the end of the 17th century-and the image they wished to have depicted in her portrait-was that of a woman of "compassion" (the word so aptly used by Korany to describe his impressions upon uncovering the original face in the portrait). In the decades following Bourgeoys' death, the ideal of sainthood gradually evolved. By the 19th century, Ber's rather naïve work no longer corresponded to the image that the sisters had of their founder. They therefore had the portrait retouched. It was not so much the material and artistic value of the portrait that was important for the community, but rather its spiritual value.

Note 15: Cloutier, Nicole, "Pierre Le Ber," in François-Marc Gagnon and Nicole Cloutier (eds.), Premiers peintres de la Nouvelle-France, Volume 1, Québec, Ministère des Affaires culturelles, 1982, p.142. The four paintings are Sainte Thérèse d'Avila and Alphonse Rodriguez, which are preserved at the motherhouse of the Grey Sisters in Montréal, Saint Charles Borromée at Maison Saint-Gabriel and lastly, Mgr de Saint-Vallier, which is held by the Priests of Saint-Sulpice of Montreal.

Note 16: Accounts of the restoration were published in Le Devoir, Montréal Matin, Montreal Star and The Gazette respectively on June 13th, June 24th and August 4th, 1964.

Note 17: Directors and curators of institutions such as the Montreal Museum of Fine Arts, the Vancouver Art Gallery, the National Gallery of Canada in Ottawa and the Musée de Peintures Canadiennes in Saint John, New Brunswick, all took a vivid interest in the portrait of Marguerite Bourgeoys. Several publishing houses, including McLelland & Stewart Ltd. and University of Toronto Press, also contacted the Congregation of Notre-Dame to request permission to reproduce the newly restored portrait in publications.

Note 18: Simpson, Patricia, Marguerite Bourgeoys and the Congregation of Notre Dame, 1665-1700, Montréal, McGill-Queen's University Press, 2005, p.237.

Note 19: Marguerite Bourgeoys was canonized by Pope John-Paul II in 1982.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Cloutier, Nicole, Pierre Le Ber, 1669-1707, M.A. (histoire), Université de Montréal, Montréal, 1973, 199 p.

Daoust, Jean-Luc, Le portrait en post mortem immédiat des religieuses au Québec : influences, analyse stylistique et fortune graphique, M.A. (Histoire de l'art), Université de Montréal, Montréal, 2007, 2 vol.

Glandelet, Charles de, La vie de la sœur Marguerite Bourgeoys, Montréal, Congrégation de Notre-Dame, 1993 [1715], 168 p.

Karch, Pierre, Les ateliers du pouvoir, Montréal, XYZ éditeur, 1995, p.51-56.

Martin, Denis, Portraits des héros de la Nouvelle-France. Images d'un culte historique, LaSalle, Hurtubise HMH, 1988, p.59-61.

Simpson, Patricia, Marguerite Bourgeoys et la Congrégation de Notre-Dame, 1665-1700, Montréal, McGill-Queen's University Press, 2007, 303 p.

Additional DocumentsSome documents require an additional plugin to be consulted

Images

-

Costume de religieuse

Costume de religieuse

de la Congrég... -

Détail de la radiogra

Détail de la radiogra

phie du portrai... -

Dévoilement de la pl

Dévoilement de la pl

aque Marguerite... -

Dévoilement de la pl

Dévoilement de la pl

aque Marguerite...

-

Document d'archive de

Document d'archive de

la Congrégatio... -

Marguerite Bourgeoys

Marguerite Bourgeoys

-

Marguerite Bourgeoys

Marguerite Bourgeoys

- Fondatrice (1... -

Marguerite Bourgeoys

Marguerite Bourgeoys

enseignant la c...

-

Marguerite Bourgeoys,

Marguerite Bourgeoys,

1620-1700 -

Marguerite Bourgeoys,

Marguerite Bourgeoys,

fondatrice des... -

Mère Marguerite Bourg

Mère Marguerite Bourg

eoys -

Religieuse de la cong

Religieuse de la cong

régation de Not...

Vidéo

Documents PDF

-

«Une découverte fascinante», Montréal Matin, 13 juin 1964, p. 7.

«Une découverte fascinante», Montréal Matin, 13 juin 1964, p. 7.

-

Analyses du portrait de Marguerite Bourgeoys

Analyses du portrait de Marguerite Bourgeoys

-

Joan Forsey, «Portrait of a Nun, Real Personality Captured», The Gazette, 4 août 1964, p. 15.

Joan Forsey, «Portrait of a Nun, Real Personality Captured», The Gazette, 4 août 1964, p. 15.