Claude Le Sauteur (1926-2007): the Enlightened Artwork of a Lighthouse Keeper

par Gauthier, Serge and Harvey, Christian

Head and shoulders above the rest; that is quite possibly the most defining characteristic of the figures found in the works of artist and painter Claude Le Sauteur (1926-2007). Although the faces can seem vague and even ill-defined at first glance, the head dominates nonetheless. It is neither tortured nor fractured. There is no veneer of surrealism; the artist's every move is composed and calculated. The tone is just right. The keen mind of a lighthouse keeper knows how to observe. Claude le Sauteur was both renowned and subtle, well-loved by both the great and small of the land. The colours found in his depictions of Quebec's landscapes, scenes and heroes are vibrant, yet soothing. Like a lighthouse keeper, Claude Le Sauteur had his eye set on the horizon, and now many are seeking to understand his stunning perspective on a facet of our national and regional history that, up until now, has almost been entirely ignored.

Out of the Shadows and Into the Light: the Rise of the Artist

Understanding Claude Le Sauteur's unique life's journey is essential to understanding his art. For it shaped him, just as it did the various artistic themes, styles and techniques developed in his works. It even had a profound impact on how his works were received by Quebec's artistic community--starting with a somewhat inauspicious debut to be followed by its eventual recognition as a key body of works recollective of a people's culture and heritage.

Few would have guessed that Claude Le Sauteur, born on October 7th, 1926, in Rivière-Pentecôte, of Quebec's Côte Nord region, was destined to become a painter. His father, Wallace Edward Le Sauteur, worked as an accountant for Canadian International Paper, and so, his many responsibilities led the family to move to Clermont, Beaupré, La Tuque and finally Trois-Rivières, where the young artist began school and spent his adolescent years.

Young Le Sauteur's love for drawing eventually led him to study fine arts, a choice that gained little approval from his father, and so he was forced him to pay for his studies with a job in the forestry industry. From 1945 to 1950, Le Sauteur studied at the École des Beaux-Arts de Québec [Fine Arts Institut] under the likes of Jean Paul Lemieux and Jean-Philippe Dallaire. Earning a living as a painter proved to be difficult, but nonetheless, in 1959, Le Sauteur married Ghislaine Laflamme--the woman with whom he would share his life until his passing on November 29th, 2007.

From 1950 to 1980, Claude Le Sauteur worked in advertising, as a freelancer with a number of magazines (Maclean's, Châtelaine, Perspectives, etc.), as well as in the printing industry (specifically in design). In 1966, he joined Cabana-Séguin, a major Montreal advertising agency, and climbed through the ranks, eventually becoming vice-president. Not only did the position make it possible for him to earn a living as a creative artist, it also allowed him to lay the foundations of the Le Sauteur style, which streamlined advertising and make it more evocative. Le Sauteur teamed up with the Just For Laughs festival in the 1980s, creating a series of drawings devoted to humour and laughter, a testament to his wider vision of the arts, as well as his renowned skill as a graphic artist and illustrator.

Claude Le Sauteur continued to paint throughout his professional career. In 1976, an exhibition of his work was held at the Galerie Georges Dor in Longueil and all the pieces shown were sold within thirty minutes. But it wasn't until his retirement in 1980, that Le Sauteur began painting full-time. Starting in 1978, he divided his time between homes in Boucherville and in Les Éboulements (Charlevoix), where he settled permanently in 1986. Taking root in Charlevoix was an important step in his growth as an artist, one that would have a profound impact on the forms and themes found in his work.

Painting Intimacy and Grandeur

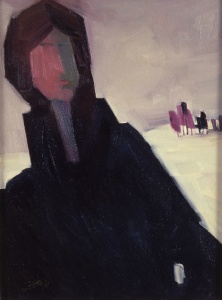

If Claude Le Sauteur's work can be bound to two universes, those universes would be "the intimate" and "the grandiose," with his most famous pieces alternating continuously between the two. A number of his pieces, whose titles are rather evocative, deal with love and day-to-day life following his two main themes: Première Rencontre [First Date] (1992), Couple de Tendresse [Tenderness] (1990), Fréquentations [Courting] (1992), Le Protecteur [The Protector] (1999). The inspiration for others grew out of his keen eye tuned to observing the surroundings: Gambade en Nature [Nature Walk] (1990), Dame-Fleur [Flower Lady] (1996), Escapade (1986). These paintings softly, almost modestly, evoke an atmosphere of intimacy.

On certain occasions, the artist, perhaps star struck by the Étoiles boréales [Northern Stars] (1993), launches into the grandiose. He depicts himself striding across the St. Lawrence in Le Sauteur sautant (2001), a particularly interesting piece that reveals the artist's desire to become a part of local heritage and even the surroundings themselves. Even though it straddles the border between figurativism and the abstract, his work is never disembodied. His desire to depict everyday life as well as his own personal journey is striking, and so, Le Sauteur leaves traces of his passing somewhere between the intimate and the grandiose-and then he invites the observer to follow in his tracks.

Totem Poles and Wayside Crosses

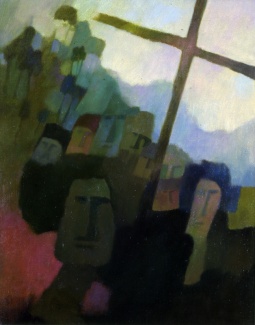

Le Sauteur's work can sometimes be seen as a social outcry. One of the most significant such moments came about in 2004 after a surprising pairing at a symposium on official languages held in Toronto. There, under a banner appropriately marked "Respect," Claude Le Sauteur's figures stood alongside British Columbian artist Emily Carr's (1871-1945) totem poles. The comparison is striking: could the origins of Le Sauteur's mysterious, slightly enigmatic figures lie in the totem? What could they teach us about traditional Quebec culture, a culture that could be as fragile as that of the First Nations? The comparison becomes even more significant in light of the Croix de Chemin paintings completed by Le Sauteur in 1982. The series of four paintings--Rassemblement Autour de la Croix, Visite à la Croix de Chemin, Autour de la Résurrection, and Procession du Vendredi Saint--is both a religious and conservationist statement, but it is most of all an anthropological statement inspired by the artist's desire to immortalize the many wayside crosses found in Les Éboulements.

Much like Emily Carr, who, with the help of ethnologist Marius Barbeau (1883-1969) of the National Museum of Canada, wished to preserve the last remaining Amerindian totem poles in British Columbia by painting them, Claude Le Sauteur strove to capture the symbolism of wayside crosses, those decaying vestiges of Quebec's fading Catholic religious heritage. Instead of merely describing certain key elements of an endangered culture, Le Sauteur's approach to the crosses recalls Carr's approach to the totems: both reach unmistakably skyward and represent a cultural heritage that promises to outlive its material incarnations. The symbolic link between the works of Claude Le Sauteur and Emily Carr undoubtedly runs deeper that would first appear at first glance.

In the Big Leagues: The Celestial Cycle

In the early 1990s, Claude Le Sauteur began painting for a number of Quebec's business elite who were drawn to the body of his works. He even painted a collector's Porsche 911 from 2003 to 2006. While his links with the world of business allowed him to paint without worrying about money, they also put him at odds with part of Quebec's intellectual community, which wasn't entirely comfortable with his artistic and financial success. Thankfully, Le Sauteur was still alive when a major exhibition to celebrate his work was held at the Musée de Charlevoix in 2007, the year of his death. The exhibition, titled Le monde Habité de Claude le Sauteur, was a huge success and was shown the following year in Montreal.

Le Sauteur's biggest "commercial" project was his celestial cycle, a series of triangular paintings commissioned by the Power Corporation to decorate the rotunda of the company's Montreal headquarters. Le Sauteur worked on the project-which was financed by Paul Desmarais-from 1992 to 1995 at his home in Les Éboulements. Despite the fact that the pieces are not easily accessible to the general public, they are nonetheless the artist's crowning achievement and a testament to the creative spirit that defined a generation. In the big leagues, there is more than the here and now, a fact that Claude le Sauteur was well aware of when he created his magnum opus.

A Return to Grassroots Culture Inspires Larger-Than-Life Legendary Quebec Figures

After his time working on the celestial cycle, Claude Le Sauteur felt the need to return to Quebec's history and countryside. The last years of his life were spent painting legends from Quebec culture. He painted a wide variety of individuals such as singer La Bolduc (1997) and Father Labelle and even Alexis le Trotteur (1997). His painting Menaud maître-draveur (1997) was particularly significant, for towards the end of his life, Le Sauteur looked back on his youth spent in the forest and became particularly passionate about the annual log drive, thereby proving once again just how deep his roots ran. It also served to establish a fitting parallel between his own life and the history of Quebec.

Like his paintings of wayside crosses, Le Sauteur's large-scale paintings of Quebec legends once again pay tribute to a slowly disappearing cultural heritage. What remains of these larger-than-life men and women in today's Quebec that sometimes forgets its own history and culture? The works of Claude Le Sauteur are there to commemorate them in their own special way. That is why, despite his failing health and old age, the artist was so committed to the task of preserving history. Once again, Le Sauteur took it upon himself to send out the clarion wake-up call and bear witness to the passing of a unique bit of heritage.

The Lighthouse Keeper

Head and shoulders above the rest, the lighthouse keeper was not one to waste time; for he spent his time observing rebuilding, relating and restoring. As a consequence, both Claude Le Sauteur's artistic legacy and his place in our cultural heritage are considerable. Should see it as a part of our past or consider it to be a glimpse of the future? A lighthouse keeper always looks into the future, and so, we should also find our way through the countryside of Charlevoix and Quebec with Claude Le Sauteur at our side, letting the breadth of his vision as the lighthouse keeper capture everything that makes us who we are.

Serge Gauthier, Ph. D.

Historian and ethnologist

Christian Harvey

Historian

Researchers at the Centre de recherche sur l'histoire et le patrimoine de Charlevoix

BIBLIOGRAPHY

"Le monde habité de Claude Le Sauteur," Revue d'histoire de Charlevoix, 57 (June 2007), 24 pages.

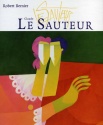

Robert Bernier, Claude Le Sauteur, Les éditions de l'Homme, 2005, 160 pages.

Additional DocumentsSome documents require an additional plugin to be consulted

Images

-

Autoportrait, 1999

Autoportrait, 1999

-

Claude Le Sauteur au

Claude Le Sauteur au

centre culturel... -

Claude Le Sauteur en

Claude Le Sauteur en

atelier -

Couple de tendresse,

Couple de tendresse,

1990

-

Portrait de Claude Le

Portrait de Claude Le

Sauteur -

Portrait de Claude Le

Portrait de Claude Le

Sauteur -

Portrait de Claude Le

Portrait de Claude Le

Sauteur -

Première rencontre, 1

Première rencontre, 1

992