The Clergy and the Origins of Quebec Cinema: Fathers Albert Tessier and Maurice Proulx

par Poirier, Christian

A handful of priests were among the first people in Quebec to use a movie camera. They were also among the first to grasp the cultural significance of cinema. Two individuals are particularly significant in this regard: Fathers Albert Tessier and Maurice Proulx. Today they are widely recognized as pioneers of Quebec cinema arts. Since 2000, Quebec cinema has been experiencing renewed popularity. Nevertheless, the key role played by the clergy in the development of a cinematographic and cultural tradition before the Quiet Revolution of the 1960s has not been fully appreciated, even though they managed nothing less than a collective heritage acquisition of cinema during a period dominated by foreign productions. After initially opposing the cinema-considering it an "imported" invention capable of corrupting French-Canadian youth-the clergy gradually began to promote the showing of movies in parish halls, church basements, schools, colleges and convents. It came to see film as yet another tool for conveying Catholic values.

A Society on the Threshold between the Traditional Past and the Modern World

During the first half of the 20th century, Quebec society underwent a process of gradual change: it became more industrialized, urbanized and economically diverse, while modern ideas such as liberalism or secularism increasingly became accepted as credible alternatives. Nevertheless, for the political and intellectual elite, the values associated with traditions, Catholicism, and rural life were still the of the French-Canadian people's identity.

The process of acquiring a home-grown cinema tradition started in a time of emerging antagonism between modern and traditional ideas in a fight for the survival of French-Canadian ideology. Paradoxically, it was an instrument that is usually the quintessential symbol of cultural modernity that would serve to preserve and promote the longstanding customs and traditions. The film making priestly Fathers did not merely use cinema as a means of supporting official ideologies, politics and the prevailing party line, although this was clearly among their preoccupations. Tessier, Proulx and other pioneering cinematic priests were also well aware of the ever-changing world they lived in. For the numerous films made by Proulx documenting his trips to the United States and Europe particularly attest to this. As such, Maurice Proulx and Albert Tessier were motivated by a desire to use film to preserve for future generations, the gradually changing socio-cultural and economic environment, much of what was even in the process of disappearing.

Albert Tessier

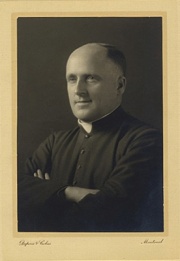

Mgr Albert Tessier (1895-1976) was a priest in the diocese of Trois-Rivières, a professor and a historian (a founding member of the Société d'Histoire Regionale de la Mauricie [Mauricie History Society]) whose films mainly focused on Quebec's regions and their inhabitants. Examples of these cinematic productions can be seen in works such as Scènes du Haut-Saint-Maurice (1932); Baie-Comeau (1938); L'lle d'Orléans, Reliquaire d'Histoire (1939); and Écoles Ménagères Régionales (1942). His productions, as well as the many presentations and conferences that he gave all across Quebec, showcased the province's country folk (Hommage à Notre Paysannerie, 1938; Le Credo du Paysan, 1942), traditions (Chante et Danse (Folklore), 1944), as well as the French-Canadian national identity that was just waiting to emerge (Pour Aimer Ton Pays, 1943). Tessier hoped to encourage his viewers to recognize the homeland in the framework of its continuity and natural evolution (La Grande Vie Tonifiante de la Forêt, 1943). "The homeland is not an abstraction..." he wrote in L'Action Nationale in 1937, "it is something that is palpable and clear for all to see: the earth, water, plants, animals, monuments, and other human creations, and especially the people themselves who perpetuate the dreams and achievements of their predecessors and toil for the generations to come."(NOTE 1) Consequently, as early as the beginning of the second decade of the 20th century, Tessier started recording on film many aspects of the day-to-day cultural existence of the French-Canadian people.

The film-making priest also wanted viewers to discover the simple things of everyday domestic life. For example, (Artisanat Familial, 1939-1942) rendered daily life in the most realistic possible manner. As a matter of fact, overall, this is one of the trademark characteristics of the world created by Quebec cinema.(NOTE 2) It is this characteristic aspect of his work that allows one to identify some of the first seeds of Quebec's venerable direct-cinema tradition. "Any redeeming feature of my films on peasant life," Tessier declared in 1939, "comes solely from how faithfully it records certain aspects of everyday existence. It has no script or production value to speak of. My camera captures ordinary life as it unfolds, totally unvarnished, the real thing. [...] As such, the film constitutes a direct lesson."(NOTE 3)

Although all of Tessier's films obviously had a religious agenda, he was nevertheless able to clearly distance himself from certain precepts and dogmas on a various number of levels. For instance, he proposed an educational reform that would encourage greater sensitivity to the natural and physical world as an integrated part of any curriculum for young students.(NOTE 4) In this way, Tessier demonstrated an empirical-mindedness typical of modernity.(NOTE 5) In fact, for him, nature was to be combined with religion, the French language and the family (across generations) to form the fundamental cultural framework for the French-Canadian people.

A member of the Société des Dix and the Royal Society of Canada, Albert Tessier was also awarded the Prix de la Langue Française [French Language Award] by the Académie Française for his life's work. Furthermore, the fact that that the Prix du Québec, a prestigious prize awarded since 1980 for individual excellence in Quebec cinema, was named after Albert-Tessier testifies to the ground-breaking importance of his productions. Winning the Tessier award is the highest honour to which a Quebec filmmaker can aspire.

Maurice Proulx

An agronomist by profession (alumnus of Laval University's Faculty of Agriculture, with a Ph.D. from New York's Cornell University), Abbot Maurice Proulx (1902-1988) was above all motivated by educational, ethnological, historical and national causes. From 1934 to 1937, he produced first feature-length sound picture filmed entirely in Quebec, a film entitled En Pays Neufs: un Documentaire sur l'Abitibi.(NOTE 6) This film was in part inspired by government initiatives intended to promote the settlement of outlaying regions and a back-to-the-land movement as a way of countering the various urban unemployment issues thought to have arisen during the Great Depression of the 1930s.(NOTE 7) His next film, En pays Pittoresque: un Documentaire sur la Gaspésie (1938-1939), dealt with the founding of the Gaspé village of Saint-Octave-de-l'Avenir, whose later abandonment would be filmed by Marcel Carrière in 1972 in a work entitled Chez Nous, C'est Chez Nous. Proulx's Parades de la Saint-Jean-Baptiste (1942) represents yet another contribution to the process of documenting French-Canadian cultural identity.

Incidentally, Abbot Proulx also made a number of films commissioned by the government. For example, Maurice Duplessis often praised his productions and frequently referred to the three "Maurices" of Quebec: himself, Cardinal Roy and Abbot Proulx. The leader of the Union Nationale was nevertheless generally rather distrustful of filmmakers and the tools of their trade. In fact, the Service de Ciné-photographie de la Province de Québec [Quebec Cinema and Photography Board], a government agency established in 1941 to promote domestic productions was the creation of Adélard Godbout's liberal government. Maurice Proulx, who had been one of Godbout's advisors, made his case in 1946: "I told [Duplessis] that this was a golden opportunity from the point of view of autonomy. I could see a sort of fire in his eyes, and the agency never had any problems with him thereafter."(NOTE 8) Duplessis even went so far as to declare that "[w]e have not looked after our domestic film industry as much as we should have."(NOTE 9) Maurice Duplessis was also the one who stated that cinema could help showcase the province "as it really is, promoting its distinct character, traditions and aspirations, as well as its cultural values, tourist attractions, and hopes for the future [...]"(NOTE 10)

For Abbot Proulx, cinema was a pedagogical tool, as well as a means of showcasing popular culture. He explored a number of themes in this regard, such as agriculture and fishing (Une Journée à l'Exposition Provinciale de Québec, 1942; Pêche au Saumon et à la Truite, 1952-1953; Cultures: Melon, Citrouille, Rhubarbe, 1958), religion (Congrès Eucharistique de Québec, 1938; Congrès Marial Ottawa, 1947), commercial cooperatives (Sucre d'Érable et Coopération, 1950; Le Cinquantenaire des Caisses Populaires, 1951), tourism (Les Routes du Québec, 1951; Points de vue de Québec, 1952-1958), and education (Centenaire de l'Université Laval, 1952; Vers la Compétence, 1955).

Although local traditions were obviously his main focus of concern, Proulx also carefully examined the developments associated with modernity (Médecine d'Aujourd'hui, 1959). He paid particular attention to the latest technical develpments in the area of agriculture (Défrichement Motorisé, 1946; La Chimie et la Pomme de terre, 1949; Hélicoptère et Agriculture, 1956; La Culture Maraîchère en Évolution, 1961). In his view, the French-Canadian people had to make use of modern tools in to emancipate themselves as a people. The film-maker also remained convinced that he was participating in an essential commemoration endeavour: "Sometimes, even frequently, I became aware of the fact that I was filming scenes of exceptional things: the everyday acts of farming people, labourers that would disappear in just few short years thereafter."(NOTE 11)

A member of the Order of Canada and the Ordre National du Québec, Abbot Proulx also participated in the creation of the National Film Board (1939) as well as the Service de Ciné-Photographie de la Province de Québec (1941), the Quebec government's film agency which, incidentally, helped promote and distribute his work all across Quebec.

Other Members of the Clergy

Other film-making priests and Catholic organizations also deserve mention, particularly Jean-Marie Poitevin, a Foreign Mission Society priest, who, in 1944, wrote and filmed À la Croisée des Chemins, Quebec's first feature-length, non-documentary film with soundtrack. In the film, he establishes a link between the survival of the French-Canadian people and their religion. Poitevin also founded the Montreal film board and became head of the International Catholic Organization for Cinema, which is based in Rome. In 1953, at the request of Cardinal Paul-Émile Léger, he created the Centre Catholique du Cinéma de Montréal, whose mission is to offer education and cinema arts training. Complete with its own documentary film department, the centre organized courses and conferences, which focus on basic cinematic elements, cinematographical genres, and film history. Its main objectives are to develop critical thinking individuals and to encourage schools to establish film clubs and associations. In the same vein, the Church called upon each convent and college in the province to hire a film education coordinator.(NOTE 12) During the 1950s, the centre also produced two major periodicals concerned with Quebec cinema: Ciné-Orientations and Séquences.

In addition, the Catholic Action youth movement chose the cinema as a study topic and in 1950 established the Commission Étudiante du Cinéma [Student Cinema Board]. In turn, the newly founded student cinema board produced yet another periodical, Découpages, which had the specific objective of demonstrating the social and cultural relevance of cinema: "Cinema reflects the soul of every nation and people. A movie expresses the sentiments, mentality, traditions, the issues, and intellectual and artistic trends of the people about which it is filmed."(NOTE 13)

From Total Oblivion to Recognition

The Quebec society of the Quiet Revolution era considered that films made before 1960 were, in the main, somewhat "backward." However, a sort of restoration and recognition took place during the 1970s, which continued up until the beginning of the 1980s. Nationalist sentiments were particularly strong around the time the Parti Québécois came to power in 1976, and so, as a result, an increasing number of documentaries showcasing Quebec's heritage and collective folklore were produced.

The life and works of Maurice Proulx are significant in this regard, for even though Father Proulx was closely associated with the Union Nationale government during the 1960s, Marcel Carrière (Chez Nous, C'est Chez Nous, 1972) and Pierre Perrault (Un Royaume Vous Attend, 1975; Le Retour à la Terre, 1976) implicitly pay tribute to him. In 1978, a retrospective study of his films organized by the Quebec government was met with enormous success. As a result, a clear link was established between his works and the development of the identity of the people of Quebec.(NOTE 14) In 1979, Proulx received an honorary doctorate from Concordia University, and in 1984 the Montreal World Film Festival commemorated his life's work. Upon his death, in 1988, it was again emphasised that Proulx had made a major contribution to the development and evolution of the collective heritage and shared memory of the people of Quebec. Normand Provencher recalled his legacy some time later: "At a time when we are decrying the fact that history is no longer being taught, here we have a golden opportunity to put the youngest among us in contact with a unique part of our heritage."(NOTE 15)

An Exceptional Contribution to Cultural Heritage

The first film-making priests who toured Quebec from 1920 to 1960 played a key role in the history of Quebec cinema. Not only were they among the world's first filmmakers to experiment with 16 mm film as an instrument for promoting culture and educating society, but they also paved the way for a national-level acquisition of cinema as an instrument for documenting society and its social evolution, all the while enabling this selfsame society to see itself on the silver screen.

With the notable exception of Tessier's empiricism and the technological developments uncovered by Proulx, this portrayal of the French-Canadian culture and its people did not always correspond to the realities and social transformations being experienced in Quebec on the economic, political, cultural and ideological levels of the time. Nevertheless, by filming certain folk traditions, customs and practices that have all but disappeared today, these priests helped preserve on film traces of a bygone way of life and worldview that is now priceless. This in and of itself is an essential contribution to the heritage of people of Quebec and of all French-Canadians

Christian Poirier

Instructor, Université Laval

NOTES

Note 1: Albert Tessier, "Pour une politique nationale," L'Action nationale, May 1937, quoted in René Bouchard, "Un précurseur du cinéma direct. Mgr Albert Tessier," Cinéma Québec, No. 51, September 1977, p. 20. [Original citation translated into English for this text]

Note 2: See Christian Poirier, Le cinéma québécois. À la recherche d'une identité? Volume 1. L'imaginaire filmique, Quebec City, Presses de l'Université du Québec, 2004.

Note 3: Quoted in René Bouchard, "Mgr Albert Tessier. Un précurseur du cinéma direct (2)," Cinéma Québec, No. 52, October 1977, p. 31.

Note 4: Albert Tessier, "Quelques réflexions d'un éducateur: paresse intellectuelle - le manuel et l'enseignement livresque - l'étude de la nature - ses bienfaits," Le Devoir, August 3rd, 1930.

Note 5: Patrick Bossé, "Politique de la lumière: Hommage à notre paysannerie de l'abbé Albert Tessier et le Bien platonicien," Nouvelles "vues" sur le cinéma québécois, No. 4, Autumn 2005. [On line] (Consulted on April 7th, 2007.)

Note 6: The first feature-length film made in Quebec was in fact Madeleine de Verchères, by J.-Arthur Homier (1922), a silent film of which, unfortunately, no copies exist.

Note 7: It should be recalled that Cardinal Jean-Marie-Rodrigue Villeneuve founded the Société de la Colonisation and that in 1935 the government of Louis-Alexandre Taschereau enacted legislation to promote settlement and a return to the regions.

Note 8: Quoted in Pierre Véronneau, "Le cinéma gouvernemental," Copie Zéro, No. 11, 1981, p. 6-12. It should be noted that Abbot Tessier was also a close advisor to Maurice Duplessis. See Patrick Bossé, op. cit. We must nevertheless emphasize that Tessier was clearly more sympathetic to collective forms and ideologies of political and economic expression, such as socialism, than was Maurice Duplessis, for example.

Note 9: Pierre Véronneau, op. cit.

Note 10: Ibid.

Note 11: Pierre Demers, "L'abbé Proulx et le cinématographe. La leçon du cinéma ‘nature'," Cinéma Québec, Vol. 4, No. 6, August 1975, p. 24.

Note 12: As a matter of fact, numerous filmmakers, including Jean Pierre Lefebvre, Michel Brault and Denys Arcand, have said that they "discovered" cinema in a classical college or parish hall, although they had no qualms about sharply criticizing the straightjacket of piety imposed by these same religious institutions.

Note 13: Découpages, No. 3, November 1950, pp. 23-24.

Note 14: Ministère des Communications, Programme Rétrospective Maurice Proulx, Direction générale du cinéma et de l'audio-visuel, 1978.

Note 15: Normand Provencher, Le Soleil, July 13, 1996.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Bouchard, René, Filmographie d'Albert Tessier, Montréal, Boréal, 1973, 179 p.

Coulombe, Michel et Marcel Jean, Le dictionnaire du cinéma québécois, Montréal, Boréal, 2006, 821 p.

Lever, Yves, Histoire générale du cinéma au Québec, Montréal, Boréal, 1995, 635 p.

« Fonds Albert Tessier », Cégep de Trois-Rivières.

« Inventaire du Fonds Maurice Proulx, cinéaste», Bibliothèque et Archives nationales du Québec. [En ligne]. (Consulted on April 6th 2007).

Poirier, Christian, Le cinéma québécois. À la recherche d'une identité ? Tome 1. L'imaginaire filmique, Québec, Presses de l'Université du Québec, 2004, 314 p.

Reines, Philip, « The Emergence of Quebec Cinema : A Historical Overview », dans Joseph I. Donohoe, Jr. (dir.), Essays on Quebec Cinema, East Lansing, Michigan State University Press, 1991, 194 p.

Rétrospective Albert Tessier, Québec, Éditeur officiel du Québec, 1977, 63 p.

Ministère des Communications, Programme Rétrospective Maurice Proulx, Direction générale du cinéma et de l'audio-visuel, 1978, 55 p.

Additional DocumentsSome documents require an additional plugin to be consulted

Images

-

L'Abbé Proulx filmant

L'Abbé Proulx filmant

un cheval de l... -

L'Abbé Proulx filmant

L'Abbé Proulx filmant

une scène de l... -

Les Prix du Québec. M

Les Prix du Québec. M

édaille du prix... -

Les Prix du Québec. M

Les Prix du Québec. M

édaille du prix...

Vidéos

-

Extrait de « Conquête constructive »

Extrait de « Conquête constructive »

-

Extrait de « En pays neufs »

Extrait de « En pays neufs »

-

Extrait de « Île aux Coudres »

Extrait de « Île aux Coudres »

-

Extrait de «En pays pittoresque »

Extrait de «En pays pittoresque »

-

Extraits de « Femmes dépareillées »

Extraits de « Femmes dépareillées »

-

Extraits de « Marguerite Bourgeoys »

Extraits de « Marguerite Bourgeoys »