Legend of Loup Lafontaine

par Marchildon, Daniel

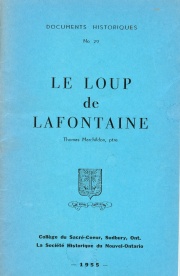

Part legend, part true story, the horrifying account of the wolf that terrorized Lafontaine, a tiny, rural, Franco-Ontarian community about 160 kilometres [100 miles] north of Toronto, was written by Thomas Marchildon, a parish priest, and published by Sudbury's Société historique du Nouvel-Ontario in 1955. It is the story of the founding of one of Ontario's oldest French-speaking villages, established at the beginning of the 19th century. Recounting the story of how the menace of an evil wolf managed to unite the divided descendants of the region's pioneer families to face a common enemy, the legend has become the enduring legacy of an inspiring author, who not only used this work of fiction to give a historical account, but also to bring the past to life in the collective memory of the community.

Article disponible en français : Légende du loup de Lafontaine

A Legend or Perhaps Just a Bit of History

When Thomas Marchildon, a parish priest and native of Lafontaine, sat down to write the legend of the Loup Lafontaine [the Lafontaine Wolf], he wanted to entertain his readers, as any author would. He also intended to educate them by way of a historical fable, in which the truth scarcely diverged from fiction (or vice versa). From the outset, in his foreword, Thomas Marchildon made an important admission: "If the events appear extraordinary, they are nevertheless true to life, for the account is-in the main-based on history. It is the result of careful research [...]. The setting, the major events and the characters in the story are all real, but certain circumstances and dialogues are imaginary."(NOTE 1)

The idea of writing the story came to Father Marchildon during the centennial celebrations of the St. Croix parish in 1955. In June, he published Le Loup de Lafontaine [hereafter referred to as The Lafontaine Wolf]. Among the events organized for the centennial were a couple of plays based on Thomas Marchildon's tale, both held at the parish hall on Sunday, July 31st, 1955. The 2:30 p.m. showing was intended for the children and the 8:00 p.m version was "for the big folk".(NOTE 2) No fewer than 38 performers from the community, including 7 children, took part in the production.

A Story of Beginnings and of Reconciliation

As penned by Father Marchildon, the legend became the tale of how the diverse groups that founded the parish were finally reconciled. Throughout the 39-page story, the priest is striving to teach readers an invaluable lesson.

Around the turn of the 20th century, the French speakers of the Lafontaine region formed not one but several communities. Four groups of French Canadians, mainly composed of farmers, had originally populated this tiny French-speaking community.

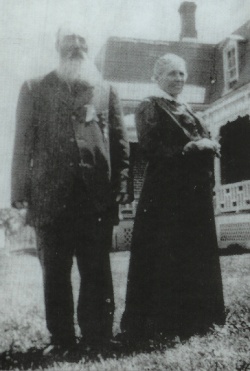

The region's initial settlers were mostly French-speaking Métis from voyageur (NOTE 3) families who came as early as 1828 to the Penetanguishene region from Drummond Island (northern Lake Huron). Members of this group founded the village of Lafontaine. Starting in 1840, three other waves of settlers from four Quebec counties (Champlain, Joliette, Vaudreuil and Soulanges) came to clear land in Huronia. The first arrivals grabbed the best land, and the others had to make do with what was left. The former became farmers, the others, lumberjacks and fishermen.

Although all of them were French-speaking Catholics, they distrusted one another to such an extent that the various members of each faction had very little contact with those outside their own group. In his introduction, Father Marchildon emphasizes the state of discord characterizing a community where the wolf, "discovering this divided world [...] felt right at home and settled in."(NOTE 4)

Even though the story is made up of characters who really existed, the author takes special care not to set his story at a specific time, instead saying simply that the drama unfolds at the beginning of the 20th century. Be that as it may, in the story, the wolf saves a little two-year-old boy named Thomas. It was not until 1988, in a recorded interview whose transcript was published in 2005, that Father Marchildon admitted that this child was actually none other than the author himself (who was born on February 8, 1900). Thus the story takes place between March 1902 and September 1903.

The Theatrical Plot and the Misdeeds of the Wolf

The story is nine-chapters long, with each chapter intended as a specific scene in which a particular adventure or event in the theatrical plot unfolds. From the outset, a sort of tension sets in and it continues to rise until the wolf dies. The main events of the story may be summarized as follows:

One March evening, Joseph Lortie and his wife Philomène are returning by buggy to their home in Methodist Point. Joseph had taken advantage of their day in town, in Penetanguishene, to toast the imminent arrival of spring with more than a few drinks. All of a sudden, from the open, ice floe-covered waters of Georgian Bay, a howl pierced the air that made the couple shiver with fear. As a still tipsy Joseph was putting the horses into to the stables for the night, a black shadow shot past him like a cannon ball. The farmer was convinced that he had seen a wolf. But Philomène scoffed at such a notion, calling him a hallucinating old drunk.

The next morning, Colbert Tessier, a sheep breeder, came upon the scene of a slaughter: 40 of his ewes lay dead, awash in a pool of their own blood. He ran to the neighbour, Philéas Beaupré, for help. The two men inspected the premises with a fine-toothed comb and discovered a set of paw prints. There could be no mistake about it: these were dog tracks, made by big dogs, such as those owned by François Labatte.

The two farmers took up their rifles and made their way to nearby Thunder Bay, to the home of François Labatte, a fisherman and descendant of the pioneering group of Métis. They confronted François, who insisted that his dogs had spent the night safely tied up. After no more than a cursory examination of the two animals' tracks, Colbert Tessier shouldered his rifle and shot the two dogs in cold blood.

Nevertheless, that very same night, Tessier heard a bloodcurdling howl that ushered in a reign of terror. Each evening thereafter, the wolf announced a new series of ravages, as his howling that cut through the night like a razor-sharp knife. The evil beast wandered throughout the concessions, making no distinction between residents with good land and those whose farms were less productive, nor between those originally from Batiscan and those from Soulanges.

The Lafontaine region soon turned into an armed camp where every man carried a rifle at all times. The best hunters and the most skilled marksmen unrelentingly stalked the wolf. Ojibways from Christian Island were recruited to track down the beast, but the wolf managed to dodge every bullet and every trap. He remained invisible, both day and night.

Strangely enough, the wolf was quite fond of children. Sometimes local kids would run into him on their way home from school and play with him as they might play with a dog. Naturally, some parents were terrified and began to keep their young ones at home.

Although fond of children, the wolf was the enemy of all lovers. Ever since his arrival, most of the young men were afraid to go to their girlfriends' place for their regular Sunday visit. Their big fear was to run smack into the wolf on their way back home. More than one promise of marriage was put to a very rough test during this dark period that lasted the whole winter and the following summer.

One day, Théophile Brunelle surprised everyone. Brunelle was blind in one eye, and had been so since childhood. He was also a very devout man with a nun for a daughter and a seminarian for a son. Théophile vowed to arrange for the singing of a Thanksgiving mass if God let him kill the wolf that was sowing terror among the population. News of his vow spread through the parish like wildfire.

A short time later, in early September, Théophile found himself in a distant corner of his 17th-concession field. All of a sudden, he saw the notorious wolf. The farmer ran home to get his dusty old rifle. When he got back to the field, he discovered that the wolf hadn't budged an inch. It was almost as though the creature had been awaiting him. Brunelle took aim with his rifle, closed his one good eye, and pulled the trigger. Miraculously, he hit the mark. But the wolf was not dead yet. Although bleeding profusely, he managed to escape. Later on, Théophile did finally find the animal's body, stretched out lifeless on the ground.

That very evening, everyone rushed to Théophile's farm to see the wolf raised up on a sort of makeshift gallows that the farmer had built on his democrat buggy, and quite the improvised gathering ensued! This was the moment of reconciliation and Théophile even persuaded Colbert Tessier to buy François Labatte some new dogs.

The following day, the entire village attended the high Thanksgiving mass offered by Théophile Brunelle. Father Joseph Beaudoin, the parish priest, took advantage of such an exceptional occasion to cement this new spirit of community unity. In triumphal tones, the priest made the following claim: "Thus the wolf is not just the author of evil but also of a very great good: he has brought all of you together [...]. A new day has dawned here in St. Croix. The wolf has marked this community with a sign, making it a real parish."(NOTE 5)

Parts of the Tale Long Forgotten, Whether for Better or For Worse

The episode of the wolf resulted in at least one very concrete change: after his tumultuous reign of terror was brought to a close, many weddings took place that united couples with ties in the various groups of the community. In this regard, Thomas Marchildon is categorical: "with the death of the wolf, the walls came tumbling down." (NOTE 6)

Another historical aspect of the story is the presence of all the place names it refers to (many of which have been long forgotten). During their trip by sled from Penetanguishene to Lafontaine, Joseph and Philomène Lortie went up Côte Copeland and Côte Boudria [a pair of hills] (p. 5). The first place name is still in use, while the second is not. They went past Coin des Dorion [Dorion's Corners] (p. 7), as it is still called today. When the couple heard the wolf howling in the distance, they thought that he was out on the ice or on Île Travers (today known as Giant's Tomb).

Little Thomas lost his way in Boyer Swamp (p. 19), a name that is practically no longer in use, much like the name Hark Creek, referring to the stream feeding this tiny swamp. Several other names appearing in the story are unknown today: Coteau des Roches [Rocky Hillside](p. 20), Côte Giroux (p. 24) and Côte du Cabestan (p. 34).

But writing a fictional account that is so close to reality is risky business, as the author himself acknowledges: "in Lafontaine, [the publication of the legend] was generally warmly received, with the exception of a few people who didn't want their names to appear-you know, especially since I didn't hesitate to say that so and so was a drunk-and so the kids weren't too proud of that!"(NOTE 7)

The Legend Outlives its Author

Since its publication in 1955, "The Lafontaine Wolf" has earned a permanent place in the Franco-Ontarian heritage of Huronia, which is today a community that includes some 3,300 French-speakers. The legend is featured in schools, as well as in documentaries such as TVOntario's 1976 program Villages et Visages [Villages and Faces], in which 76-year-old Thomas Marchildon tells the story with the air of a mischievous child.

Before his death in 1991, Father Marchildon transferred his copyright for the written version of the story to the Centre d'Alphabétisation-Huronie, a community organization dedicated to eliminating illiteracy among adult French speakers of the region. In 2007, the Centre published a new version of "The Lafontaine Wolf," accompanied by five illustrations. I [the author of this text] have adapted a version of the legend for eighth-grade students(NOTE 8) and have written a story, entitled Le Retour du Loup de Lafontaine [The Return of the Lafontaine Wolf],(NOTE 9) , which is based on the legend and deals with the issue of cultural assimilation. The theatrical adaptation of the legend was also revived by students from Lafontaine's French Catholic elementary school and was performed for the community on May 30th, 1997.

Thus the legend of the wolf is now an official part of the Lafontaine village's history. This becomes abundantly clear as we read the three paragraphs dedicated to the tale in a 1995 monograph published in English by the Township of Tiny. Entitled Recollections: Township of Tiny, the text draws a particularly astonishing conclusion: "The one positive thing to come out of this ′reign of terror′ was that it united the people of the region, both English and French, against a common foe."(NOTE 10)

Although there were indeed English speakers in the Lafontaine region at the time of the story, the conflicts reported in the tale only involved various groups of French Canadians and French-speaking Métis. Hence, as is often the case with legends, the story of the Lafontaine wolf has been both distorted and appropriated many times over the years.

An Ongoing Celebration: The Festival du Loup

In 2002, a century after the events took place, Lafontaine residents established the Festival du Loup [The Wolf Festival], a cultural heritage event that is held on the third weekend of July, It includes music-often of a traditional variety-as well as a historical exhibit. On many occasions during the festival, an amateur theatre company has performed a theatrical version of the legend, reinterpreting it in their own special way by combining history with contemporary situations.

Shortly after the founding of the Festival du Loup, a four-kilometre [2.5 mile] section of County Road 26, which stretches from the corner of Chemin de Lafontaine to Thunder Bay, was officially renamed Chemin du Loup [Wolf Lane]

The

legend of the Lafontaine wolf has therefore served the purposes of history by

firmly anchoring the origins of this longstanding Franco-Ontarian community in

the collective memory of the population, all the while enriching and sustaining

the cultural life and heritage of the region.

Daniel Marchildon

Writer from Huronia-which he still calls home-and author of 20 or so

publications,

including eight novels and a number of historical works.

NOTES

Note 1: Thomas Marchildon, Le Loup de Lafontaine, Sudbury, Société Historique du Nouvel-Ontario, doc. 29, 1955, p. 3. [Original Citation translated into English-all citations in this text have been translated from French into English].

Note 2: L'Église de Sainte-Croix, 1855 - 1955, document souvenir des fêtes du centenaire, 1955, p. 8.

Note 3: Refers to travelling fur trappers of the 18th and 19th centuries.

Note 4: Marchildon, Le Loup de Lafontaine, op. cit., p. 4.

Note 5: Marchildon, Le Loup de Lafontaine, op. cit., p. 39.

Note 6: Denise Jaiko, "La Légende du Loup de Lafontaine: L'auteur a raconté ...", (Partie 3), journal Le Goût de vivre, Septembre 1st, 2005, p. 10.

Note 7: Jaiko, op. cit., (Part 2) page 11, August 18th, 2005.

Note 8: Daniel Marchildon, "La légende du loup de Lafontaine," in Recueil de lecture 7e et 8e année, Ottawa: Centre franco-ontarien de ressources pédagogiques, 2001, p. 124-131.

Note 9: Daniel Marchildon, "Le retour du Loup de Lafontaine," short story published in four parts in the journal Le Goût de vivre, Penetanguishene, between December 4th, 1997 and January 15th, 1998.

Note 10: Township of Tiny Historical and Heritage Committee, Recollections: Township of Tiny, 1995, p. 21.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

L'Église de Sainte-Croix, 1855 - 1955, document souvenir des fêtes du centenaire, 1955, 100 pages.

Jaiko, Denise, La Légende du Loup de Lafontaine: L'auteur a raconté ..., transcription of an interview with Thomas Marchildon recorded by Denise Jaiko in 1988 and published in six parts in Le Goût de vivre, (Partie 1) p. 14, 4 août 2005, (Partie 2) page 11, 18 août 2005, (Partie 3) page 10, 1er septembre 2005, (Partie 4) page 19, 15 septembre 2005, (Partie 5) page 9, 6 octobre 2005, (Partie 6) page 7, 20 octobre 2005.

Marchildon, Daniel, La légende du loup de Lafontaine, dans Recueil de lecture 7e et 8e année, Centre franco-ontarien de ressources pédagogiques, Ottawa, 2001, p. 124-131.

Marchildon, Daniel, La Huronie, Centre franco-ontarien de ressources pédagogiques, Ottawa, 1984, 285 pages.

Marchildon, Thomas, Le Loup de Lafontaine, Sudbury, Société historique du Nouvel-Ontario, doc. 29, 1955, 39 pages.

Marchildon, Thomas, Le Loup de Lafontaine (new edition with illustrations by Julie Robb), Penetanguishene, centre d'alphabétisation-Huronie, 2007, 49 pages.

Marchildon, Thomas, Verner et Lafontaine, Sudbury, Société historique du Nouvel-Ontario, doc. 8, 1945, 62 pages.

Township of Tiny Historical and Heritage Committee, Recollections Township of Tiny, 1995, 189 pages.

Villages et Visages : Penetanguishene et Lafontaine, TFO, Toronto, 1976, 30 minute program.