Beauregard Town District of Baton Rouge, Louisiana

par Clermont, Guy

Unlike the famous "Vieux Carré" (Old Square) in New Orleans, the Beauregard Town district of Baton Rouge is still little known even though it is a rare example of French urban planning in the United States. Visitors to the area can feast their eyes on a vast palette of colours and architectural styles as they stroll along the narrow, shady streets of the precinct. The district reflects the unique history of this state capital over which no fewer than seven national flags have flown... not to mention the famous Indian "red stick" which gave the city its name. In 1980, this exceptional urban architectural heritage site was listed on the U.S. National Register of Historical Places.

Article disponible en français : Quartier Beauregard à Bâton-Rouge, Louisiane

An Almost Entirely Intact Historic District

The Beauregard Town district is essentially a residential neighbourhood that can be subdivided into four distinct areas. To the west, the lower part of the neighbourhood is made up of a relatively narrow strip along on the banks of the Mississippi, which is today separated from the river by an imposing levee. It includes a commercial area (including a casino, hotel, etc.) called Catfish Town and a vast administrative and cultural complex (offices, cultural centre, theatre, etc.) called River Center (formerly the River Centroplex). To the east, in the upper part of the district there is a residential area that is split down the middle by a main street lined with modern style commercial buildings. Much like River Center, this main thoroughfare is not in keeping with the architectural harmony of the neighbourhood as a whole. And even though both areas are located within the historical boundaries of the Beauregard Town district, neither is protected by the regulations that govern historical places.

To the south and east, the district is cut off from the rest of the city by two major highways (Interstates 10 and 110), whereas the commercial and administrative centres of the city of Baton Rouge stretch out to the north. Taken from a bird's eye view, it would seem that the two residential areas of the historic district are like jewels of greenery and tranquillity set into the city's relatively aggressive urban landscape. The venerable old residences line shady streets, offering visitors a stroll through the town's historical past.

The vast majority of the neighbourhood's buildings are one-story houses with open verandas. A number of different styles can be found side by side. The oldest homes are authentic examples of the Creole architectural style - but these are few and far between-whereas Shotgun and the Queen Anne (or Neoclassical) style homes are much more common. They are often huddled together along narrow streets bordered with lawns and flowers and generously shaded by bushes and trees (live oaks, American elms, magnolias and West Indian lilacs).

The historic public buildings are clearly more impressive and varied in character, ranging from the astonishing Gothic revival-style Old State Capitol Building-which Mark Twain described as an "architectural falsehood,"-to the former governor's residence, which is like a miniature version of the White House. There is also the granite Neo-classical courthouse, which dominates the architectural landscape of the area.

The birth of a brand-new town

In 1806, the Americans had been in possession of Louisiana for barely three years (since December 1803), but the little town of Baton Rouge was already strategically located on the left bank of the Mississippi River, just as it had since the time of the Spanish. And so, it seemed destined for a bright future, which is probably why Elie Toutant Beauregard decided to transform his plantation at the southernmost edge of old Baton Rouge (down by the banks of the Mississippi) into the heart of a new town in the classical French colonial architectural tradition.

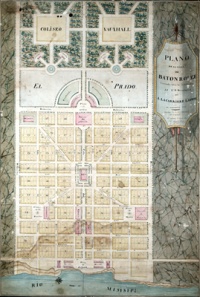

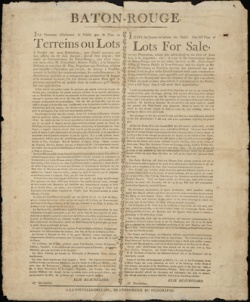

After having rejected an initial design by Frederick Walther, because they were not grandiose enough for Beauregard's ambitions, the plantation owner asked Ira Cook Kneeland to draw up new plans to be submitted for July 22, 1806, the date set for the public sale of the land tracts. But Kneeland was unable to deliver the plans in time, which put Beauregard in such an awkward position that he became furious and decided to entrust the project to a young French architect, Arsène Lacarrière Latour, who had just arrived in New Orleans. The new project was ready in two months and was presented to the public in December of 1806.

Lacarrière Latour's concept of Baton Rouge was firmly anchored to the Mississippi riverfront and bordered on three sides by wide and shady boulevards. It would be connected on all sides to a central thoroughfare (today's Government Street), which started at the river and ran eastward uninterrupted to its midpoint, where a large square (Place Royale, often referred to today as Royal Square) opened up. Planned as the town's central hub, no fewer than 16 different streets converged on the square, including four that cut diagonally through the grid layout of the community to connect with smaller open squares. Each of the town's seven squares would were meant to showcase public buildings: the cathedral in Royal Square, the governor's mansion in Place d'Armes, and the hospital, the college, the market, etc. in various other squares.

Adopting this structure would make it possible to break with the rigidity of an almost military style grid pattern and offer residents convivial recreational spaces. Similar to the open squares, the Coliseum and Vauxhall (NOTE 1) (both urban concepts very much in style in Europe at the time) were also intended to offer a break with the town's rigid urban planning. These public spaces were to be situated to the east of town in a pastoral area and-as opposed to the rest of the city-the site was designed very much in the style of riverfront tracts.(NOTE 2) The half-moon layout of Place d'Armes afforded Lacarrière Latour's plan even more flexibility and added a Baroque touch. In this way, by adding popular urban and architectural elements for which London, Paris and New Orleans were renowned (which was soon to be the case of Washington as well) (NOTE 3), Lacarrière Latour sought to give an entirely exceptional character this small town on the edge of a still largely unexplored wilderness. There was also evidence of the influence of the North American reality down by the riverfront, where the tight grid structure opened up into a large square named after Christopher Columbus. It was intended to accommodate warehouses and customs offices, which symbolised the town's promising future in doing a flourishing commerce with far-flung regions. The roadway that ran alongside the river, the Camino Real, now known as River Street lead out of town and eventually became the community's connection with the rest of the continent.

The street names, most of which have been kept to this day, are a reflection of the town's Franco-Spanish heritage and its open-mindedness in regards to the outside world. There are even streets named after France and Spain, which are located on each side of Government Street. Of the adjoining parallel streets, which originally bore the names of the four main continents, only Europe and America have been retained, whereas the signs for Asia and Africa streets have been replaced by the new ones commemorating the Mayflower and the State of Louisiana. The streets running north and south are mostly named after saints, and almost so exclusively so that a painter in charge of making street signs during the mid-19th century actually "beatified" the few illustrious figures who could not claim the status of sainthood, although they were sufficiently popular to take their place beside St. Louis or St. James. Thus, for many decades Napoleon Street was called St. Napoleon Street. The error was even reproduced on official maps of Baton Rouge. The diagonal streets for their part bear the names of important local figures, such as GranPre Street, named in honour of the man who was the Franco-Spanish governor of Western Florida at the time.

Beauregard Town and the Caprices of History

The Beauregard Town project encountered a few substantial obstacles not long after it was launched. The first was the passing of Elie Beauregard in 1809 and the second was the incorporation of Western Florida [today's Southern Alabama and Mississippi State, which border on the Gulf of Mexico and the Mississippi River] into the United States in 1810. Because the newly included territories gave the United States access to the Gulf and to the mouth of the Mississippi, the town was no longer a strategically located port and so tracts sold poorly. None of the main buildings were actually finished and, in 1816, the city blocks set aside for their construction were transferred back to the Beauregard family, as it had been agreed upon in case they were not built upon within 10 years. A few decades later, these parcels of land were subdivided so they could be put up for sale, which lead to several squares of the original plan not being developed.

In 1846, Baton Rouge was designated the Louisiana state capital. This gave a fresh boost to regional development and brought about the first modifications to Lacarrière Latour's plan for the layout of the community. In fact, the State Capitol Building was constructed on two city blocks at the northwest edge of Beauregard Town, where the Indian "red stick" may well have been located. (NOTE 4) The changes brought on by the construction of the capitol complex lead to the disappearance of the northern end of Repentance Street, the only street that did not run in a straight line in conformity with the original plan's grid pattern.

The new State Capitol Building drew government employees who settled on tracts located near the legislative complex and along North Boulevard, which became a fashionable promenade, as well as the town's main thoroughfare. This was to the detriment of Government Street, which in Lacarrière Latour's layout was to be the main artery. Other public buildings were to follow, bringing about a few additional changes to the original plan. For example, during the 1850s, four empty city blocks on South Boulevard were combined so a home for the deaf, mute and blind could be constructed. Furthermore, Royal Square, which had heretofore been left vacant, was divided in 1858 to create an easement to Government Street.

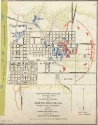

On August 5, 1862, during the Civil War, the town was the site of a battle between Northern forces that had arrived a few months earlier and a Confederate Army that attempted in vain to recover it. A number of buildings were destroyed, mostly in Catfish Town, and the commander of the Northern Army even considered razing the town to the ground to keep it from falling into the hands of the opposition, but he eventually changed his mind. Nevertheless, the Capitol Building, which served as a prison during the war, was ravaged by fire in December 1862. During the remainder of the war, the town housed a military hospital and accommodated as many as 17,000 soldiers. Once the war was over, thousands of freed slaves settled in Catfish Town.

It took Baton Rouge some time to recover from the effects of the Civil War, particularly because the seat of government was temporarily transferred to New Orleans. However, in 1882, the return of the government to Baton Rouge and the arrival of the railway breathed a fresh breath of new life into the town. The Capitol Building was restored and the population started to grow again. Buyers for the remaining available tracts in Beauregard Town were found. This was the period during which most of the homes in existence today were constructed. However, none of Lacarrière Latour's plans for developing the areas beyond East Boulevard were ever implemented. On the other hand, due to dredging that had been undertaken in the harbour, the capacity of the port was significantly increased and it was able to accommodate increasingly larger boats. Thus, Catfish Town became the town's industrial and commercial centre-particularly after a train station was built at the foot of the Capitol Building in 1925.

This type of urban development could have sealed the fate of Beauregard Town, wiping all traces Lacarrière Latour's city planning completely off the map. However, the 1932 construction of the new State Capitol in a neighbourhood at the north end of Baton Rouge shifted the city's centre of activity towards the north and away from Beauregard Town. And so Beauregard's brainchild became frozen in time in such a way that the main elements of the initial project were preserved until the 1960s.

The Restoration of Beauregard Town Begins

From the end of the 1960s until the mid 1980s, Beauregard Town would once again be impacted by the onslaught of modernization. The construction of two raised freeways blocked views from the east and west, and an onramp would henceforth encroach upon the town's historical perimeter, drawing a significant stream of vehicles into the neighbourhood. Government Street, now dominated by an immense radio tower, became a main artery for automobile traffic, as well as a site for unplanned commercial development. The construction of the Riverside Centroplex wiped out the northern half of Catfish Town, with the exception of the Old State Capitol Building, whereas the southern part would shortly thereafter become home to a casino, a large hotel and restaurants, all located in buildings that were somewhat reminiscent of the warehouses of yesteryear. The railroad station was converted into an art and science museum situated next to a war veteran's memorial museum whose key exhibit is a Second World War destroyer anchored off the Catfish Town harbour front. These transformations brought about a renewal of activities, but threatened the historical aspect of Beauregard Town. At this point, local residents, as well as municipal authorities, realized that something had to be done to protect the site.

A neighbourhood restoration campaign was launched. The Town was listed on the U.S. National Register of Historical Places, and the Plan Baton Rouge, which follows the principles of the New Urbanism movement, was drawn up at the end of the 1990s. This project intended to restore the human dimension to the neighbourhood by recovering land that had been taken up by infrastructures created to accommodate the automobile. The objective was to reduce traffic throughout the entire neighbourhood and restore the unifying, central role of Royal Square. The plan proposed to transform the square into a park, while keeping a few of the existing public buildings (including the church and the fire station). Slowly but surely, the old residences would be restored by historic building enthusiasts (salaried workers, teachers, lawyers, etc.) drawn to the area by the historical authenticity and quiet tranquillity of a neighbourhood that offered an ideal residential location that was close to businesses and public services.

In spite of the unsightly scars inflicted by the uncontrolled urbanization of the 1970s, the framework of the 1806 plan is still visible today and the restoration initiatives that have been undertaken now serve to ensure the preservation and perpetuation of Lacarrière Latour's visionary plans, making Beauregard Town one of the rare existing examples in the United States of what is often referred to as the genius of French urban planning.

Guy Clermont

Conference

speaker (North American civilization)

Université de Limoges

NOTES

Note 1. Gardens equipped with facilities in which the general public could attend shows and concerts and take part in outdoor activities.

Note 2. Areas subdivided into strips of land running perpendicular to waterways in the typical New France style. These tracts gave each settler direct access to the river. The buildings were constructed near the banks, across a road that ran along the river. The fields, meadows and woods were located towards the back end of the tracts.

Note 3. A few similarities can be seen between Lacarrière Latour's plan and the projects designed by Pierre C. L'Enfant that served as at the basis of the plans for Washington, D.C.

Note 4. This referred to a pole (or tree trunk) that marked the established boundary between the hunting grounds of two Native tribes. Such sticks were also used for ceremonial purposes. Animal heads were impaled upon them, which explains the scarlet colour of such markers.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Bappert, Thescus, Beauregard Town. Preservation of an Urban Landscape, Baton Rouge, Louisiana State University (thèse de Master), 1983, 154 p.

"Beauregard Town", National Register of Historic Places, Louisiana (Consulté le 1er juillet 2007).

Carleton, Mark T., River Capital. An Illustrated History of Baton Rouge, Woodland Hills, California, Windsor Publications Inc., 1981, 304 p.

City Parish Planning Commission, Historic Baton Rouge. A Revised Study of Historic Buildings and Sites, Baton Rouge, mars 1970, révisé en 1975.

Favrot, J. St. Claire, "Baton Rouge, the Historical Capital of Louisiana", Louisiana Historical Quarterly, n° 12, 1929, p. 611-629.

Garrigoux, Jean, Un aventurier visionnaire : l'étrange parcours d'un Français aux Amériques, Aurillac, Cantal, Société des lettres, sciences et arts « La Haute-Auvergne », 1997, 352 p.

Langlois, Gilles-Antoine, Des villes pour la Louisiane française. Théorie et pratique de l'urbanistique coloniale au 18e siècle, Paris, L'Harmattan, 2003, 448 p.

"Plan Baton Rouge", Center for Planning Excellence (Consulté le 1er juillet 2007).

Rodrigue, Sylvia, et Phillips Faye, Historic Baton Rouge. An Illustrated History, San Antonio, Texas, Historical Publishing Network, 2006, 148 p.

Additional DocumentsSome documents require an additional plugin to be consulted

Images

-

"État de Louisiane".

"État de Louisiane".

"Faculté des Le... -

"Le quartier Beaurega

"Le quartier Beaurega

rd aujourd'hui"... -

"Le quartier Beaurega

"Le quartier Beaurega

rd aujourd'hui"... -

"Louisiane et Floride

"Louisiane et Floride

occidentale. E...

-

"Plan de Baton Rouge,

"Plan de Baton Rouge,

aujourd'hui Be... -

Ancien Capitole (faça

Ancien Capitole (faça

de ouest avec g... -

Ancien Capitole (faça

Ancien Capitole (faça

de ouest) -

Ancienne résidence du

Ancienne résidence du

gouverneur, si...

-

Boulevard du Sud (réd

Boulevard du Sud (réd

uit à deux voie... -

Les forces en présenc

Les forces en présenc

e et le plan de... -

Maison de style class

Maison de style class

ique (604, rue ... -

Maison de style néo-c

Maison de style néo-c

lassique ( 626,...

-

Maison de style néo-c

Maison de style néo-c

lassique (301, ... -

Maison de style Queen

Maison de style Queen

Ann -

Maison de style Roman

Maison de style Roman

tic Mode (136, ... -

Parking du River Cent

Parking du River Cent

er (rue du Gouv...