Champlain’s astrolabe: the journey of a mythical Canadian heritage object

par Bergeron, Yves

An astrolabe that may have belonged to the explorer Samuel de Champlain was discovered in 1867 near the Ottawa River. More than a century later, this precision instrument known as "Champlain's astrolabe" has become one of Canada's most highly prized heritage objects and it now belongs to the permanent collection of the Canadian Museum of Civilization. The unique journey of this iconic object of Canadian history resembles a fictional tale, with first Champlain as the central figure, and then the astrolabe. We invite you to discover how this 17th century navigation instrument became a Canadian heritage symbol.

The Astrolabe Today

In 1989, Canada's Department of Communications took the necessary steps to acquire Champlain's astrolabe, which for a number of years had been in the hands of the New-York Historical Society, in order to integrate it into the collections of the Canadian Museum of Civilization that was just about to open to the public. During the 1967 Centennial Celebrations of the Canadian Confederation, reproductions of the astrolabe had already been offered to several Canadian and American museums. Statues of Champlain holding his astrolabe were also erected. The one in Ottawa has become one of Canada's most photographed monuments. The proliferation of images of the astrolabe contributed to the heritage-building process in which this mythical object became a Canadian heritage item and Samuel de Champlain, father of Canada.

The 19th Century Discovery of the Astrolabe

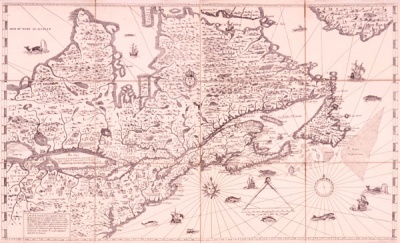

Accompanied by Nicolas de Vignau, Champlain explored the Ottawa River during the summer of 1613 in search of a passage to China and the riches of the East. The two men apparently proceeded upstream to the present Gould's Landing, then crossed a series of lakes and portaged between them, in order to avoid the Ottawa rapids, until they reached Allumette Island. In his account of the voyage, Champlain begins by providing precise measurements of the latitude, an indication that he used his astrolabe. Later he offers a simple description of the area without specifying the latitude, suggesting that the astrolabe was lost, in spite of the fact that nowhere did Champlain report the disappearance of his precious measuring instrument, although he included many other details in his report.

The history of the heritage acquisition of Champlain's astrolabe began some 254 years later, in August 1867. That year, a teenager named Edward George Lee stumbled upon "a brass disk in the groundbeneath a fallen tree. His father, John Lee, a farmer from the Cobden, Ontario, area, had been doing clearing work on the shores of Green Lake." (NOTE 1) This is how Jean-Pierre Chrestien, curator of the Canadian Museum of Civilization, reports the discovery of the astrolabe in a major work about Champlain published in 2004.

At the same time, young Lee discovered other objects, including "a rusty iron chain, small containers or plates embedded in copper, and two engraved or emblazoned tumblers." All of these objects were handed over to the owner of the land, one Captain Overman.

In an account published in 1880, a certain Mr. Scadding indicates that "the tumblers were sold to a peddler then melted down, while the copper objects were reused for, among other purposes, to repair a hole in a canoe." Thus, the only evidence that would have made it possible to identify the origin of all these objects with any certainty was lost forever. As for the astrolabe, it was apparently kept for "a number of months on the officers' desk of the steamship serving the shores of Muskrat Lake, and the public learned of the event only a number of years later." (NOTE 2)

In 1870, Father Charles-Honoré Laverdière published the collected works of Champlain, thus rekindling interest in the astrolabe. An artist by the name of Alexander Jamieson Russell produced a leaflet in which he asserted that the astrolabe in question had indeed belonged to Champlain, while providing only circumstantial evidence for his claim.

That same year, Orasmus Holmes Marshall, a book collector from Buffalo, commented on this discovery and stated that he agreed with Russell's arguments (although here mained prudent as to the origins of the astrolabe), since, in his opinion, the evidence remained inconclusive. In the end, the editor of the Canadian Journal of Science, Literature, and History took up these arguments during the 1879 conference of the Canadian Institute. As Chrestien points out, this was when "Champlain's astrolabe assumed its place in Canadian history." (NOTE 3)

During this time, the astrolabe changed hands several times. Captain Overman sold the instrument to his boss, R. W.Cassels. Then Cassels's heirs sold it to the American collector Samuel V. Hoffman, who bequeathed it to the New-York Historical Society in 1942. Over the course of this journey, the astrolabe was shown in a number of exhibits, most notably "at the Smithsonian Institute in Washington, the Peabody Museum in Salem, [Mass.] and the Canada Science and Technology Museum in Ottawa." (NOTE 4)

Legitimate Questions

Certain details concerning the history of this astrolabe inevitably raise a number of questions. In 1613, only a few learned individuals knew how to use this "high-tech" instrument that enabled Champlain to map with precision the new territory he was exploring. So why didn't he mention its disappearance in his account of this voyage, in which he provided a great number other details? How is it that the astrolabe was found with other objects having no obvious connection with Champlain's expedition? One must not also forget that there is only oral tradition to support the discovery of the astrolabe in 1867, since it was 12 years before the first text reporting such a finding was actually published. It is also curious that the astrolabe just happened to be discovered in August 1867, a few weeks after the confederation of Canada on July 1st, 1867.

Moreover, in 1879, just as Canada's territorial expansion westward was causing a major crisis involving the Manitoba and Saskatchewan Metis, three publications were produced to confirm the authenticity of Champlain's astrolabe. At this time, the Canadian government was funding the construction of a railway line to unite the country from east to west, with the goal of linking British Columbia to the rest of the country. One thing is sure: Canada was still a young country whose history remained to be written. The discovery of Champlain's astrolabe could not have come at a better time.

The Confederation Train

In 1967, the Centennial celebrations of the Canadian Confederation caused re-emergence of the nearly forgotten history of Champlain's astrolabe, which was then in the possession of the New-York Historical Society in the United States. As a part of the extensive program to commemorate national history, the Canadian government borrowed the astrolabe in order to make replicas, which it then distributed to various museums. The government incorporated the object into the grand historical account it was planning to present to the Canadian people, particularly in the context of the confederation train project that crossed the country presenting an exhibit interpreting the history of Canada. Implicit in this whole process was the obvious desire to legitimize the authenticity of the astrolabe and, at the same time, to make Canadian history better known and appreciated. Following the same line of thinking, in 1989, the Canadian government acquired the astrolabe and integrated it into the new Canadian Museum of Civilization collections, a gesture that resonated with meaning - both from the point of view of the country's history and its identity.

Further Questions on the Astrolabe's Authenticity

The curator of the Canadian Museum of Civilization, Jean-Pierre Chrestien, points out that the year 1603 is engraved on the astrolabe's 13 cm (5 in) disk and that metallurgic analyses confirm that it was indeed manufactured in Europe at the beginning of the 17th century. But there is nothing to guarantee that it comes from France, nor is there any proof that it actually is the astrolabe that belonged to Champlain. We do know that before his death, Champlain bequeathed all his worldly goods to Father Charles Lalemant who may have inherited this astrolabe... if it was not lost during the voyage of 1613. Furthermore, Chrestien has hypothesized that perhaps it was Father Lalemant himself who lost it during one of his trips between Huronia and Quebec. Chrestien also wonders whether Father Lalemant might not "have given it to somebody else, to Father Daniel for example? Did Champlain have several astrolabes? He probably did since he could not have drawn up his maps with such great precision using the tiny astrolabe discovered at Green Lake." (NOTE 5) An so there are a number of hypotheses that cast doubt on the authenticity of "Champlain's astrolabe" which need to be taken into consideration.

A Tale of Heritage

In reality, this fabulous account is primarily based on the desire of all the players involved to believe it. The story is too good not to be true... Like all heritage and museum artifacts, Champlain's astrolabe plays a commemorative role in this case to remind us of the accomplishments of the Father of New France.

What is yet evenmore remarkable, is that the historical account follows the traditional structure of a tale or legend, which can be broken down into the following six major parts:

1. The initial situation places the protagonist into the plot and setting of the story. 2. The hero then embarks upon a quest intended to satisfy a specific need. 3. The hero must venture far afield in order to find what he is looking for. 4. During his voyage, the hero faces obstacles and ordeals. 5. The hero usually receives some form of magical assistance that enables him to successfully complete his quest. 6.The hero reaches his goal, satisfying the original need, and all's well that ends well.

The passages of Champlain's story that are directly related to the astrolabe match this structure rather faithfully.

Champlain enlisted in an exploration voyage in response to a clearly expressed request made by King Louis XIII, who ordered him to "find the easiest way to go throughthe said country to the Kingdom of China and the East Indies." (NOTE6) Champlain therefore had to venture far from Quebec City and explore an unknown territory fraught with obstacles. The Algonquins that he met at Île aux Allumettes provided the "magical" assistance in question by exposing the lies told by his French guide (Nicolas de Vignau) and by giving him reliable information that convinced him to return to Quebec City - a decision that not prove entirely fruitful for Champlain, but it did mark a return to routine life in the colony. The voyage was also momentous in that he had made significant degree of progressin acquiring knowledge of the territory.

Similar to Champlain's voyage to Île aux Allumettes, the story of the heritage - acquisition process involving Champlain's astrolabe also takes on the classic form of a heroic tale. Here the astrolabe itself is the protagonist of the story. The quest evoked by the tale is the discovery of Canada's origins and the nation's history.

The discovery of the astrolabe takes us back to the voyage Champlain made along the Ottawa Riverand throughout the vicinity in 1613. It also marks the second symbolic founding of Canada since the astrolabe was discovered - curiously enough-in 1867, in the same region that would eventually become the nation's capital. After having laid at rest beneath the earth for 254 years, Champlain's astrolabe changed hands a number of times and ended up in the United States for a long period of exile. Whereas anumber of authors and collectors were convinced that the astrolabe was authentic, others were not so sure. Hence this authenticity had to be proven once and for all. The historians who addressed the question could not confirm the astrolabe's historical value beyond a reasonable doubt. Instead they used this object as a pretext for providing an historical account. The instrument temporarily returned to Canada in 1967 for the Centennial Celebrations of the Confederation. The Canadian government made replicas that were circulated among the museums of the country's network, but the original remained in the United States. Finally, following lengthy negotiations between the Canadian and American governments, in 1989, the coveted object returned home to stay. It was on the auspicious occasion of the inauguration of the Canadian Museum of Civilization, formerly the Museum of Man. Its specific commission is to be "the national depository of human history."

From this time on, the Museum would make Champlain's astrolabe an iconic object that would take its place at heart of a permanent exhibit dedicated to Canadian history. The story ends happily, like a traditional fairy tale. But the doubts expressed during recent years have led the Museum to take a more nuanced position on the astrolabe's authenticity. A renewed debate concerning the astrolabe arose during the 400th anniversary celebrations marking the founding of New France and the beginning of French cultural presence in North America. When commenting on museum artifacts, Jacques Hainard writes that it is a typical case "of contextualized objects vs. utilized objects."

What Does the Astrolabe Account Tell Us?

In the case of Champlain's astrolabe, it is not so much the artifact that is of importance as it is the tale that has been woven around it: a tale of exploration, loss, and discovery, as well as one of origins and identity. The history surrounding Champlain's astrolabe is so unusual that the Canadian Museum of Civilization Web site now provides the following version of the account:

"In May 1613, Samuel de Champlain, the French explorer-cartographer, travelled up the Ottawa River. To avoid the rapids, he chose a course through a number of small lakes near Cobden, Ontario. Champlain and his men were forced to portage and to climb over and under fallen logs at one particularly difficult point by Green Lake, now also known as Astrolabe Lake. It was here, according to several 19th century authors, that Champlain lost his astrolabe. If this is correct, the astrolabe remained where it had fallen for 254 years. Eventually, a 14 years old farm boy named Edward Lee found it in 1867 while helping his father clear trees by Green Lake." (NOTE 7) "Champlain's astrolabe" has proven to bea commemorative object that serves as time machine, taking us back to the very beginnings of the acquisition of the territory by the various European nations. It can also be seen as a veritable "relic" of our history that has made it possible to legitimize the historical origins of Canada. The astrolabe evokes the mythical account of the initial founding of the country by Champlain, as well as its rebirth with the signing of the Canadian confederation. Although Champlain's tomb has yet to be discovered, we have his astrolabe to remind us of the keyrole that he played in Canada's history.

Yves Bergeron

Professor of Art History and Museology

Université du Québec à Montréal

NOTES

1: Jean-Pierre Chrestien, "L'astrolabe de Champlain," Champlain. La naissance de l'Amérique française, Nouveau monde (Septentrion, 2004), p. 351. (Excerpt translated into English for this text.)

2: Ibid.

3: Ibid., p. 352.

4: Ibid.

5: Ibid., p. 353.

6: Marcel Trudel, "Champlain, Samuel de,"Dictionary of Canadian Biogaphy Online.

7: http://www.civilization.ca/cmc/exhibitions/tresors/treasures/222eng.shtml HYPERLINK"http://www.civilization.ca/cmc/exhibitions/tresors/treasures/222eng.shtml"

Additional DocumentsSome documents require an additional plugin to be consulted

Images

-

Calèche dans la rue d

Calèche dans la rue d

u petit-champla... -

Carte géographique de

Carte géographique de

la Nouvelle-Fr... -

Champlain et ses comp

agnons en expéd... -

Champlain et son Abit

Champlain et son Abit

ation.

-

Champlain, sur le «Do

Champlain, sur le «Do

n de Dieu», pas... -

Commemoration Service

Commemoration Service

at Champlain M... -

Construction du Don d

Construction du Don d

e Dieu de Champ... -

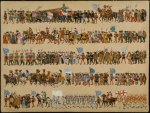

Défilé Historique du

Défilé Historique du

tricentenaire d...

-

Don de Dieu à l'ancre

Don de Dieu à l'ancre

,1908. -

Don de Dieu et Indomp

Don de Dieu et Indomp

table,1908. -

Équipage du «Don de D

Équipage du «Don de D

ieu»,1908. -

Étude pour « l'arrivé

e de Samuel de ...

-

Juge Charles Langelie

Juge Charles Langelie

r en Samuel de ... -

L'Abitation de Champl

L'Abitation de Champl

ain,1908. -

La rue champlain, à Q

uébec -

La rue petit-champlai

n, à Québec

-

Lac champlain au crép

Lac champlain au crép

uscule. de l'al... -

Le marché champlain,

Le marché champlain,

Québec -

Ruines de la maison d

Ruines de la maison d

e Samuel de Cha... -

Samuel de Champlain a

Samuel de Champlain a

nd His Girl Wif...